ISSN 0017-0615 the GISSING JOURNAL “More Than Most Men Am I Dependent on Sympathy to Bring out the Best That Is in Me.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amy Poehler, Sarah Silverman, Aziz Ansari and More on the Lost Comic

‘He was basically the funniest person I ever met’ Amy Poehler, Sarah Silverman, Aziz Ansari and more on the lost comic genius of Harris Wittels By Hadley Freeman Monday 17.04.17 12A Quiz Fingersh Pit your wits against the breakout stars of this year’s University Challenge, and Bobby Seagull , with Eric Monkman 20 questions set by the brainy duo. No conferring The Fields Medal has in secutive order. This spells out the 5 1 recent times been awarded name of which London borough? to its fi rst woman, Maryam Mirzakhani in 2014, and was What links these former infamously rejected by Russian 7 prime minsters: the British Grigori Perelman in 2006. Which Spencer Perceval, the Lebanese academic discipline is this prize Rafi c Hariri and the Indian awarded for? Indira Gandhi? Whose art exhibition at Tate Narnia author CS Lewis, 2 Britain this year has become 8 Brave New World author the fastest selling show in the Aldous Huxley and former US gallery’s history? president John F Kennedy all died on 22 November. Which year The fi rst national park desig- was this? 3 nated in the UK was the Peak District in 1951. Announced as a Which north European national park in 2009 and formed 9 country’s fl ag is the oldest in 2010, which is the latest existing fl ag in the world? It is English addition to this list? 15 supposed to have fallen out of the heavens during a battle in the University Challenge inspired 13th century. 4 the novel Starter for Ten. -

FACTUAL CATALOGUE 2020-2021 Including

HAT TRICK INTERNATIONAL FACTUAL CATALOGUE 2020-2021 Including... FACTUAL CATALOGUE CONTENTS FACTUAL CATALOGUE CONTENTS FACTUAL ENTERTAINMENT SECRETS OF YOUR SUPERMARKET FOOD 11 RIVER COTTAGE KEY CONTACTS TALKING ANIMALS: TALES FROM THE ZOO 17 AMAZING SPACES DENMARK 20 THE BALMORAL HOTEL: AN EXTRAORDINARY YEAR 25 A COOK ON THE WILD SIDE 38 SARAH TONG, Director of Sales AMISH: WORLD’S SQUAREST TEENAGERS 2 THE BIG BREAD EXPERIMENT 26 HUGH’S 3 GOOD THINGS: BEST BITES 38 Australia, New Zealand, Global SVOD THE BIG C & ME 13 ATLANTIC EDGE 16 HUGH’S THREE HUNGRY BOYS - SERIES 1 39 Email: [email protected] A VERY BRITISH HOTEL CHAIN: INSIDE BEST WESTERN 24 THE DETONATORS 6 HUGH’S THREE HUNGRY BOYS - SERIES 2 39 Tel: +44 (0)20 7184 7710 A YEAR ON THE FARM 16 THE GREAT BRITISH DIG: HISTORY IN YOUR BACK GARDEN 22 RIVER COTTAGE AUSTRALIA 39 BANGKOK AIRPORT 24 THE GREAT BRITISH GARDEN REVIVAL 18 RIVER COTTAGE BITES 38 BRADFORD: CITY OF DREAMS 8 THE LADYKILLERS: PEST DETECTIVES 16 RIVER COTTAGE BITES: BEST BITES 38 JONATHAN SOUTH, Senior Sales Executive BREAKING DAD 5 THE LAST MINERS 2 RIVER COTTAGE CATALOGUE 1999-2013 40-41 Canada, Latin America, Portugal, Spain, USA BRITISH GARDENS IN TIME 18 THE MILLIONAIRES’ HOLIDAY CLUB 24 Email: [email protected] BROKE 9 THE REAL MAN’S ROAD TRIP: SEAN AND JON GO WEST 5 FACTUAL / SPECIALS Tel: +44 (0)20 7184 7771 CABINS IN THE WILD WITH DICK STRAWBRIDGE 19 THE ROMANIANS ARE COMING 9 CELEBRITY TRAWLERMEN: ALL AT SEA 6 THE YEAR WITH THE TRIBE, A TASTE OF THE YORKSHIRE DALES 42 ELFYN MORRIS, Senior Sales Executive -

Print Journalism: a Critical Introduction

Print Journalism A critical introduction Print Journalism: A critical introduction provides a unique and thorough insight into the skills required to work within the newspaper, magazine and online journalism industries. Among the many highlighted are: sourcing the news interviewing sub-editing feature writing and editing reviewing designing pages pitching features In addition, separate chapters focus on ethics, reporting courts, covering politics and copyright whilst others look at the history of newspapers and magazines, the structure of the UK print industry (including its financial organisation) and the development of journalism education in the UK, helping to place the coverage of skills within a broader, critical context. All contributors are experienced practising journalists as well as journalism educators from a broad range of UK universities. Contributors: Rod Allen, Peter Cole, Martin Conboy, Chris Frost, Tony Harcup, Tim Holmes, Susan Jones, Richard Keeble, Sarah Niblock, Richard Orange, Iain Stevenson, Neil Thurman, Jane Taylor and Sharon Wheeler. Richard Keeble is Professor of Journalism at Lincoln University and former director of undergraduate studies in the Journalism Department at City University, London. He is the author of Ethics for Journalists (2001) and The Newspapers Handbook, now in its fourth edition (2005). Print Journalism A critical introduction Edited by Richard Keeble First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX9 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Selection and editorial matter © 2005 Richard Keeble; individual chapters © 2005 the contributors All rights reserved. -

Reciprocity in Experimental Writing, Hypertext Fiction, and Video Games

UNDERSTANDING INTERACTIVE FICTIONS AS A CONTINUUM: RECIPROCITY IN EXPERIMENTAL WRITING, HYPERTEXT FICTION, AND VIDEO GAMES. A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 ELIZABETH BURGESS SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES 2 LIST OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Declaration 4 Copyright Statement 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Chapter One: Materially Experimental Writing 30 1.1 Introduction.........................................................................................30 1.2 Context: metafiction, realism, telling the truth, and public opinion....36 1.3 Randomness, political implications, and potentiality..........................53 1.4 Instructions..........................................................................................69 1.41 Hopscotch...................................................................................69 1.42 The Unfortunates........................................................................83 1.43 Composition No. 1......................................................................87 1.5 Conclusion...........................................................................................94 Chapter Two: Hypertext Fiction 96 2.1 Introduction.........................................................................................96 2.2 Hypertexts: books that don’t end?......................................................102 2.3 Footnotes and telling the truth............................................................119 -

Millions of Pounds Worth of Masterpieces Have Disappeared from Art Galleries Around the UK (To Be Replaced by Copies for a National Sky Arts Competition)

Press release EMBARGOED FOR 00.01HRS Friday 1 July 2016 Photo: Giles Coren and Rose Balston, © PA/Doug Peters Millions of pounds worth of masterpieces have disappeared from art galleries around the UK (to be replaced by copies for a national Sky Arts competition) A top secret operation last night saw millions of pounds worth of priceless masterpieces removed from the collections of galleries and museums around the UK. In a further twist, the seven paintings – all by celebrated British Artists – have been switched for copies. The heist has been coordinated by Sky Arts, with permission from the galleries, to launch a month-long national art competition for a new TV series called Fake! The Great Masterpiece Challenge. Only the museum curators, the production team from IWC Media, and presenters Giles Coren and art historian Rose Balston, know which pictures are real and which have been replaced. Throughout July, members of the public of all ages and experience are invited to use their detective skills to spot the seven copies hiding in plain sight on the walls of six galleries in Cardiff, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London and Manchester. All seven displays will also be available for investigation online, via the competition website: skyartsfake.com Those with a keen eye, who manage to correctly identify the ‘fakes’, stand the chance of being invited to take part in the series finale. The finalists will compete to win a specially commissioned copy of their very own. “You don’t have to be an art historian to have a go at this,” says Phil Edgar-Jones, Director of Sky Arts, “all you need is a sense of curiosity and an eye for detail. -

Cheltlf12 Brochure

SponSorS & SupporterS Title sponsor In association with Broadcast Partner Principal supporters Global Banking Partner Major supporters Radio Partner Festival Partners Official Wine Working in partnership Official Cider 2 The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival dIREctor Festival Assistant Jane Furze Hannah Evans Artistic dIREctor Festival INTERNS Sarah Smyth Lizzie Atkinson, Jen Liggins BOOK IT! dIREctor development dIREctor Jane Churchill Suzy Hillier Festival Managers development OFFIcER Charles Haynes, Nicola Tuxworth Claire Coleman Festival Co-ORdinator development OFFIcER Rose Stuart Alison West Welcome what words will you use to describe your festival experience? Whether it’s Jazz, Science, Music or Literature, a Cheltenham Festival experience can be intellectually challenging, educational, fun, surprising, frustrating, shocking, transformational, inspiring, comical, beautiful, odd, even life-changing. And this year’s The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival is no different. As you will see when you browse this brochure, the Festival promises Contents 10 days of discussion, debate and interview, plus lots of new ways to experience and engage with words and ideas. It’s a true celebration of 2012 NEWS 3 - 9 the power of the word - with old friends, new writers, commentators, What’s happening at this year’s Festival celebrities, sports people and scientists, and from children’s authors, illustrators, comedians and politicians to leading opinion-formers. FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 10 - 89 Your day by day guide to events I can’t praise the team enough for their exceptional dedication and flair in BOOK IT! 91 - 101 curating this year’s inspiring programme. However, there would be no Festival Our Festival for families and without the wonderful enthusiasm of our partners and loyal audiences and we young readers are extremely grateful for all the support we receive. -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL (Neo-)Victorian

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL (Neo-)Victorian Impersonations: 19th Century Transvestism in Contemporary Literature and Culture being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD in the University of Hull by Allison Jayne Neal, BA (Hons), MA September 2012 Contents Contents 1 Acknowledgements 3 List of Illustrations 4 List of Abbreviations 6 Introduction 7 Transvestites in History 19th-21st Century Sexological/Gender Theory Judith Butler, Performativity, and Drag Neo-Victorian Impersonations Thesis Structure Chapter 1: James Barry in Biography and Biofiction 52 ‘I shall have to invent a love affair’: Olga Racster and Jessica Grove’s Dr. James Barry: Her Secret Life ‘Betwixt and Between’: Rachel Holmes’s Scanty Particulars: The Life of Dr James Barry ‘Swaying in the limbo between the safe worlds of either sweet ribbons or breeches’: Patricia Duncker’s James Miranda Barry Conclusion: Biohazards Chapter 2: Class and Race Acts: Dichotomies and Complexities 112 ‘Massa’ and the ‘Drudge’: Hannah Cullwick’s Acts of Class Venus in the Afterlife: Sara Baartman’s Acts of Race Conclusion: (Re)Commodified Similarities Chapter 3: Performing the Performance of Gender 176 ‘Let’s perambulate upon the stage’: Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem ‘All performers dress to suit their stages’: Tipping the Velvet ‘It’s only human nature after all’: Tipping the Velvet and Adaptation 1 Conclusion: ‘All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players’ Chapter 4: Cross-Dressing and the Crisis of Sexuality 239 ‘Your costume does not lend itself to verbal declarations’: -

Aasmah Mir & Stig Abell Until in a World of Noise and Confusion, Bedtime with Carole Walker

LIVE FROM MONDAY 29TH JUNE 2020 Tim Levell, Programme will be able to enjoy engaging and Director, Times Radio: informed discussions from the moment they wake up at breakfast Our promise to listeners is that, with Aasmah Mir & Stig Abell until in a world of noise and confusion, bedtime with Carole Walker. Times Radio will offer intelligent and thought-provoking news, analysis On Fridays and the weekends we and conversation, hosted by respected have big names and personalities to and entertaining presenters. keep our listeners hooked, including Michael Portillo, Giles Coren, Cathy We have brought together the Newman and Ayesha Hazarika. peerless journalistic expertise of The Times and The Sunday Times with Our listeners can expect expert guests the speech radio and podcasting and commentators and for us to cover experience of Wireless, the company the biggest news stories of the day, behind talkSPORT, talkRADIO and from politics and business to arts and Virgin Radio UK. sport, and feature themes that are relevant to their daily lives. Our focus has been to create a stellar line-up of warm, witty and expert Times Radio will be available 24 hours presenters from a range of broadcast a day on DAB, via app, smart speaker backgrounds. Across our Monday and times.radio from Monday 29th to Thursday schedule our listeners June 2020. Weekday Weekend PRESENTERS Aasmah Mir and Stig Abell with Matt Chorley Times Radio Breakfast 10am-1pm Monday to Thursday 6am-10am Monday to Thursday Times Red Box editor Matt Chorley is one of the Waking up listeners to informative discussion, quality most respected political journalists operating in news and compelling analysis at breakfast are Sony Gold Westminster, providing insider analysis in his Red Box award-winning broadcaster Aasmah Mir and broadcaster newsletter and award-winning podcast. -

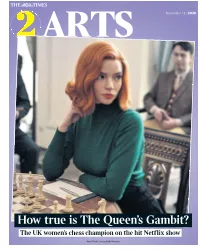

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle. -

Tamarkan Convalescent Camp Sears Eldredge Macalester College

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Book Chapters Captive Audiences/Captive Performers 2014 Chapter 5. "The aT markan Players Present ": Tamarkan Convalescent Camp Sears Eldredge Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks Recommended Citation Eldredge, Sears, "Chapter 5. "The aT markan Players Present ": Tamarkan Convalescent Camp" (2014). Book Chapters. Book 17. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks/17 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Captive Audiences/Captive Performers at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 152 Chapter 5: “The Tamarkan Players Present” Tamarkan Convalescent Camp It was early December 1943 when Brigadier General Arthur Varley and the first remnants of A Force from Burma arrived at their designated convalescent camp in Tamarkan, Thailand, after a long journey by rail. As their train traversed the wooden bridges and viaducts built by their counterparts, they passed the construction camps where the POWs in Thailand anxiously awaited their own redeployment back to base camps. When they entered Tamarkan, they found a well-ordered camp with a lean-to theatre left by the previous occupants. Backstory: October 1942–November 1943 Tamarkan was “the bridge camp”—the one made famous by David Lean’s film The Bridge on the River Kwai, based on the novel by Pierre Boulle.i There were, in fact, two bridges built at Tamarkan: first a wooden one for pedestrian and motor vehicle traffic that served as a temporary railway trace until the permanent concrete and steel railway bridge could be completed just upriver of it. -

The Limehouse Golem’ by

PRODUCTION NOTES Running Time: 108mins 1 THE CAST John Kildare ................................................................................................................................................ Bill Nighy Lizzie Cree .............................................................................................................................................. Olivia Cooke Dan Leno ............................................................................................................................................ Douglas Booth George Flood ......................................................................................................................................... Daniel Mays John Cree .................................................................................................................................................... Sam Reid Aveline Mortimer ............................................................................................................................. Maria Valverde Karl Marx ......................................................................................................................................... Henry Goodman Augustus Rowley ...................................................................................................................................... Paul Ritter George Gissing ................................................................................................................................ Morgan Watkins Inspector Roberts ............................................................................................................................... -

Fall Tv Preview Specialties Cast Wider Nets, While Conventionals Strive to Stay on Top

THE BATTLE FOR EYEBALLS: FALL TV PREVIEW SPECIALTIES CAST WIDER NETS, WHILE CONVENTIONALS STRIVE TO STAY ON TOP IN THE RIGHT RETINA, ONE OF CORUS STIFLES SCREAM, BOWS THE NEW COMBATANTS BROADER-FACETED DUSK BRAND OF THE YEAR STEP CHANGE CCoverJul09.inddoverJul09.indd 1 77/10/09/10/09 99:55:18:55:18 AMAM SAVE THE DATE October 7 Design Exchange An exploration of cutting-edge media executions with global impact. Presenting Sponsor To book tickets call Presented by Joel Pinto at 416-408-2300 x650 For sponsorship opportunities contact Carrie Gillis at [email protected] atomic.strategyonline.ca SST.14386.Atomic.ad.inddT.14386.Atomic.ad.indd 1 77/13/09/13/09 55:30:26:30:26 PMPM CONTENTS July/August 2009 • volume 20, issue 12 4 EDITORIAL Instead of campaign, think election 10 6 UPFRONT How Canada fared in Cannes, Caramilk’s 16 secret revealed and answers to other life-altering questions 10 WHO Bud Light’s Kristen Morrow brings the bevco’s booze cruise to Canada 14 CREATIVE Pepsi and Coke take a page from the same book of warm, fuzzy feelings 16 DECONSTRUCTED Beer wars: Kokanee vs. Keith’s (people have gone to battle for lesser things) 19 FALL TV 14 Find out what the big nets have lined up, which new shows will burn out or fade away and how specialties are evolving to woo new audiences (and advertisers) 48 FORUM Will Novosedlik on the unrelenting power 19 of TV and Sukhvinder Obhi on getting inside consumers’ brains – literally 50 BACK PAGE Lowe Roche breaks down an agency’s thought process…this explains why there’s so much Coldplay in commercials ON THE COVER Our very cool (and a little creepy) cover image was brought to us by the dark minds at Dusk, the newly rebranded Corus specialty channel replacing Scream this fall.