Operational Guidance Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings

11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings July 2006 Mumbai train bombings One of the bomb-damaged coaches Location Mumbai, India Target(s) Mumbai Suburban Railway Date 11 July 2006 18:24 – 18:35 (UTC+5.5) Attack Type Bombings Fatalities 209 Injuries 714 Perpetrator(s) Terrorist outfits—Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT; These are alleged perperators as legal proceedings have not yet taken place.) Map showing the 'Western line' and blast locations. The 11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings were a series of seven bomb blasts that took place over a period of 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and India's financial capital. 209 people lost their lives and over 700 were injured in the attacks. Details The bombs were placed on trains plying on the western line of the suburban ("local") train network, which forms the backbone of the city's transport network. The first blast reportedly took place at 18:24 IST (12:54 UTC), and the explosions continued for approximately eleven minutes, until 18:35, during the after-work rush hour. All the bombs had been placed in the first-class "general" compartments (some compartments are reserved for women, called "ladies" compartments) of several trains running from Churchgate, the city-centre end of the western railway line, to the western suburbs of the city. They exploded at or in the near vicinity of the suburban railway stations of Matunga Road, Mahim, Bandra, Khar Road, Jogeshwari, Bhayandar and Borivali. -

The Shiromani Akali Dal and Emerging Ideological Cleavages in Contemporary Sikh Politics in Punjab: Integrative Regionalism Versus Exclusivist Ethnonationalism

143 Jugdep Chima: Ideological Cleavages in Sikh Politics The Shiromani Akali Dal and Emerging Ideological Cleavages in Contemporary Sikh Politics in Punjab: Integrative Regionalism versus Exclusivist Ethnonationalism Jugdep Singh Chima Hiram College, USA ________________________________________________________________ This article describes the emerging ideological cleavages in contemporary Sikh politics, and attempts to answer why the Shiromani Akali Dal has taken a moderate stance on Sikh ethnic issues and in its public discourse in the post-militancy era? I put forward a descriptive argument that rhetorical/ideological cleavages in contemporary Sikh politics in Punjab can be differentiated into two largely contrasting poles. The first is the dominant Akali Dal (Badal) which claims to be the main leadership of the Sikh community, based on its majority in the SGPC and its ability to form coalition majorities in the state assembly in Punjab. The second pole is an array of other, often internally fractionalized, Sikh political and religious organizations, whose claim for community leadership is based on the espousal of aggressive Sikh ethnonationalism and purist religious identity. The “unity” of this second pole within Sikh politics is not organizational, but rather, is an ideological commitment to Sikh ethnonationalism and political opposition to the moderate Shiromani Akali Dal. The result of these two contrasting “poles” is an interesting ethno-political dilemma in which the Akali Dal has pragmatic electoral success in democratic elections -

UC Riverside UCR Honors Capstones 2018-2019

UC Riverside UCR Honors Capstones 2018-2019 Title Sikh Sovereignty: The Relentless Battle for Khalistan Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7947d6tp Author Mundi, Harkirat Publication Date 2019-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California By A capstone project submitted for Graduation with University Honors University Honors University of California, Riverside APPROVED _______________________________________________ Dr. Department of _______________________________________________ Dr. Richard Cardullo, Howard H Hays Jr. Chair, University Honors Abstract Table of Contents Khalsa Akhbar ........................................................................................................................... 2-5 Sikh Sovereignty: The Relentless Battle for Khalistan ..............................................................6 Origins of Sikh Sovereignty .........................................................................................................7 The Right to Khalistan ...............................................................................................................11 Anti-Colonial Nationalism .........................................................................................................14 Subaltern Studies ........................................................................................................................17 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................19 -

Punjab Police: Fabricating Terrorism Through Illegal Detention and Torture

PUNJAB POLICE: FABRICATING TERRORISM THROUGH ILLEGAL DETENTION AND TORTURE June 2005 to August 2005 An ENSAAF Report October 2005 Punjab Police: Fabricating Terrorism through Illegal Detention and Torture TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 About ENSAAF ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Frequently Used Terms ………………………………………………………………………………… 3 I. Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 II. Introduction …………………………...…………………………...………………………….............. 5 Human Rights Abuses in Punjab: 1984 to 1995 …………………………..................... 5 Impunity for Human Rights Abuses …………………………...…………………………...... 7 Alleged Revival of the Militancy …………………………...…………………………............ 8 Study on Abuses Committed in Recent Militancy-Related Arrests ………………… 10 II. Legal Framework …………………………...…………………………...…………………………..... 11 International Law …………………………...…………………………...………………………….. 11 Domestic Legal Framework …………………………...…………………………................... 11 III. Human Rights Abuses Committed in Recent Arrests ……………………………………… 14 Information on Detainees …………………………...…………………………...................... 14 Illegal and Incommunicado Detention …………………………...………………………….. 15 Allegations and Charges …………………………...…………………………...…………………. 17 Torture …………………………...…………………………...…………………………................... 18 Targeting of Immediate Family Members …………………………...……………………… 20 IV. Recommendations to the Governments of Punjab and India ………………………….. 22 ENSAAF 1 October 2005 Punjab Police: Fabricating Terrorism through Illegal Detention -

Of 4 28Th March 2012 India Contests WHO Figures for Multi-Drug Resistant

India contests WHO figures for multi-drug resistant TB The union government contested the WHO figures that put the number of Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) cases in India at 63,000, saying there were only 10,267. As many as 38,287 suspected cases were examined till the end of 2011 and of them, 10,267 have been diagnosed with MDR-TB and 6,994 put on treatment, according to TB India-2012 the annual status report of the Revised National TB Control Programme (RNCTP) brought out by the Health Ministry. The World Health Organisation, in its report released on the eve of World TB Day, said India had an estimated 63,000 cases of notified MDR-TB in 2010, the highest in South East Asia. It also put the MDR-TB prevalence estimates at 2.3 per cent among new cases and 12-17 per cent among re-treatment cases. However, due to the size of the population and the number of TB cases reported annually, India ranks second among the 27 MDR-TB high-burden countries world wide after China. Though India is the second most populous country, it has more new TB cases annually than any other. In 2009, out of the estimated global annual incidence of 9.4 million cases, two million were estimated to have occurred in India. It is estimated about 40 per cent of the Indian population is infected with TB bacillus. Court sticks to orders, wants Rajoana hanged on March 31 Dismissing the plea for deferring the execution of Balwant Singh Rajoana, convicted in the Beant Singh assassination case, Additional District and Sessions Judge Shalini Nagpal has ordered that he be hanged, as scheduled, on March 31. -

IND39635 – Jathedar Jagtar Singh 2 December 2011

Country Advice India India – IND39635 – Jathedar Jagtar Singh 2 December 2011 1. Is there information on a religious group called the Jathedar Jagtar Singh Group carrying out attacks and issuing threats in Haryana? No information was located regarding the Jathedar Jagtar Singh Group. The term „jathedar‟ means „captain‟. According to the website of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, also known as the Parliament of the Sikh Nation, jathedar refers to “a Chief of a band of Sikh volunteers who have enrolled themselves into a unit for whole time service in the cause of the Panth, or Sikh objectives”. In the present day, “a jathedar remains a local political boss in Sikh politics owing his allegiance to the Shiromani Akali Dal which might be one or more than one organisation, each claiming itself as the true and genuine spokesman for the Sikh causes”.1 A number of sources refer to individuals belonging with names similar to Jathedar Jagtar Singh. In 2007, Jathedar Jagtar Singh Hawara was convicted and sentenced to death for the assassination of former Punjab Chief Minister Beant Singh.2 3 Hawara escaped from Burail jail in January 2004, although was re-arrested in Delhi.4 5 A blog website reported in October 2007 that “Jathedar Jagtar Singh Hawara [o]f Sikh Freedom Group Babbar Khalsa” had also been falsely accused of carrying out “the Delhi Cinema bombings”.6 In 2008, Sirsa News reported that a Jathedar Jagtar Singh Akali from Gurmat Gian Missionary College in Ludhiana, Punjab, attended a Sikh training camp in Haryana, where he “played -

IJSA June 2012

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS JUNE 2012 Volume 22 No. 1 Published By: The Sikh Educational Trust Box 276, 9768 - 170th St, NW EDMONTON, AB T5T 5L4 CANADA E-mail: <[email protected]> http://www.yahoogroups.com/group/IntJSA ISSN 1481-5435 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS JUNE ISSUE VOLUME 22 EDITORIAL ADVISORS Dr S S Dhami, MD Dr B S Samagh Dr Surjit Singh Prof Gurtej Singh, IAS Usman Khalid New York, USA Ottawa, CANADA Williamsville, NY Chandigarh President, Rifah Party of Pakistan J S Dhillon “Arshi” M S Randhawa Dr Sukhjit Kaur Gill Gurmit Singh Khalsa MALAYSIA Ft. Lauderdale, FL CA Chandigarh AUSTRALIA Editor in Chief: Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon The Sikh Educational Trust Box 276, 9768-170th St, NW Edmonton, AB T5T 5L4 E-mail:[email protected] NOTE: Views presented by the authors in their contributions in the journal are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Editor in Chief, the Editorial Advisors, or the publisher. SUBCRIPTION: Canadian $85.00 per anum plus 5% GST plus postage and handling (by surface mail) for institutions and multiple users. Personal copies: Canadian $30.00 plus & 5% GST plus postage and handling (surface mail). Orders for the current and forthcoming issues may be placed with the Sikh Educational Trust, Box 276, 9768-10 St, NW, EDMONTON, AB T5T 5L4 CANADA. E-mail: [email protected] The Sikh Leaders, Freedom Fighters and Intellectuals To bring an end to tyranny it is a must to punish the terrorist -Baba (General) Banda Singh Bahadar Sikhs have only two options: slavery of the Hindus or struggle for their lost sovereignty and freedom -Sirdar Kapur Singh, ICS, MP, MLA and National Professor of Sikhism I am not afraid of physical death; moral death is death in reality Saint-soldier Jarnail Singh Khalsa Martyrdom is our ornament -Bhai Awtar Singh Brahma (General) We do not fear the terrorist Hindu regime. -

DIDR, Inde : Le Babbar Khalsa International (BKI), Ofpra, 07/10/2015

INDE Note 7 octobre 2015 Le Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations aux agents chargés du traitement des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/ lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf], se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Le Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) 1. Une organisation sikhe fondamentaliste Le Babbar Khalsa1 International (BKI) est une organisation qui est proche d’une secte religieuse sikhe, l’Akhand Kirtani Jatha (AKJ) ; nombre de ses membres en sont issus. L’AKJ ne lutte pas principalement contre l’Etat central, mais contre les nirankaris, une autre secte sikhe, qu’elle considère comme hérétique. -

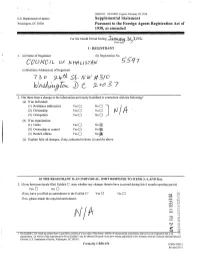

Council of Ichfluzrm B'547 (C) Business Address(Es) of Registrant 7 3 0 %^Tk Si, A/ U/ #3/O

OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended r For Six Month Period Ending JfyrwHAiy|_3_j b\yJl0)'X ' (Insert date/ I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Council of icHfluzrM b'547 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 7 3 0 %^tk Si, A/ U/ #3/O 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) YesD NoD (2) Citizenship YesD NoD rJlA (3) Occupation YesD NoD J (b) If an organization: (1) Name YesQ No a (2) Ownership or control YesD Nop, (3) Branch offices YesD No a (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3, 4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No n Ifyes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes __ No • rsj If no, please attach the required amendment. |ss3 m m C3 /v CO 15 TO r\> o 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles ot incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an JTS organization. (A waiver ofthe requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Pakistan's Plan for Khalistan

Cover story PUNJAB MILITANCY The ISI is plotting to revive a dead dream. Ensconced in Lahore, two of Khalistan movement’s most dreaded militants are fanning the flames of a deep-seated anger. By Asit Jolly ndia’s most wanted Khalistan terrorist lives in plush military- style quarters, adjoining Lahore’s Allama Iqbal International Airport. Wadhawa Singh Babbar remains busy plotting carnage against his home country with his Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) hosts. The 65-year-old grey-bearded head of perhaps the deadliest Khalistani terror group, Babbar Khalsa IInternational (BKI), along with his ISI minders, remains engaged in trying to revive the long-defeated Khalistan movement in Punjab. On the walls surrounding his operations centre are detailed section maps not only of Punjab but also of adjoining north Indian states that are the BKI’s extended battlefield. Like chess pawns, multi-coloured pins are moved around on these maps, marking potential targets. With ISI-sponsored militant groups in comparative disarray in Kashmir, Pakistan’s long-stated ambition of “inflicting death by a thousand cuts” on its larger neighbour is being pursued through well-funded and equipped Khalistani groups. Their deadly intent was evident in the seizure on October 12 of an RDX cargo in Ambala, Haryana. Recent events in Punjab have rejuvenated militant Sikh groups. In 2007, there were sectarian clashes between Sikhs and followers of the breakaway Sacha Sauda sect. More recently, there was widespread public indignation over the rejection of the mercy petititon of Devinderpal Singh Bhullar. Bhullar faces a death sentence for killing nine persons in an attempt on former Youth PRABHJOT GILL Congress chief Maninderjeet Singh Bitta in 1993. -

Counter-Insurgency in India: Observations from Punjab and Kashmir

Counter-Insurgency in India: Observations from Punjab and Kashmir by Hamish Telford INTRODUCTION Over the past 15 years, India has experienced separatist challenges from a variety of ethnic and religious minorities - Sikhs in Punjab, Muslims in Kashmir and various tribal groups in Assam and other parts of the Northeast Frontier. Between 1983 and 1993, over 20,000 people were killed in Punjab, and since 1989 a greater number of people have been killed in Kashmir. While the insurgency in Punjab developed slowly between 1978 and 1984, it crumbled quickly between 1992 and 1994. The insurgency in Kashmir continues unabated. In fact, it seems to have been transformed into a proxy war with Pakistan.1 These crises have exacted a serious toll on the Indian state. Ethnic and religious conflict is not new in South Asia. Indian independence, in fact, was achieved amid one of the greatest religious conflicts of the century. The legacy of partition in India placed two issues outside the boundaries of acceptable political discourse. First, the government of India made clear shortly after independence that demands for the political reorganization of the Indian state along religious lines would not be entertained. Second, it made equally clear that separatist claims would not be tolerated.2 Indeed, the Indian Constitution requires all political candidates and elected officials to swear that they will "bear true faith and allegiance to the constitution of India" and that they will "uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India."3 The insurgencies in Punjab and Kashmir over the past 15 years have seriously challenged these two fundamental rules of Indian political practice. -

IJSA June 2013

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS JUNE 2013 Volume 23 No. 1 Published By: The Sikh Educational Trust Box 724, 9768 - 170th St, NW EDMONTON, AB T5T 5L4 CANADA E-mail: <[email protected]> http://www.yahoogroups.com/group/IntJSA ISSN 1481-5435 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS JUNE 2013 ISSUE VOLUME 23 NO. 1 EDITORIAL ADVISORS Dr S S Dhami, MD Dr B S Samagh Dr Surjit Singh Prof Gurtej Singh, IAS Usman Khalid New York, USA Ottawa, CANADA Williamsville, NY Chandigarh President, Rifah Party J S Dhillon “Arshi” M S Randhawa Dr Sukhjit Kaur Gill Gurmit Singh Khalsa MALAYSIA Ft. Lauderdale, FL Chandigarh AUSTRALIA Managing Editor and Editor in Chief: Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon The Sikh Educational Trust Box 276, 9768-170th St, NW Edmonton, AB T5T 5L4 E-mail:[email protected] NOTE: Views presented by the authors in their contributions in the journal are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Editor in Chief, the Editorial Advisors, or the publisher. SUBCRIPTION: Canadian $85.00 per anum plus 5% GST plus postage and handling (by surface mail) for institutions and multiple users. Personal copies: Canadian $30.00 plus & 5% GST plus postage and handling (surface mail). Orders for the current and forthcoming issues may be placed with the Sikh Educational Trust, Box 276, 9768-10 St, NW, EDMONTON, AB T5T 5L4 CANADA. E-mail: [email protected] The Sikh Leaders, Freedom Fighters and Intellectuals To bring an end to tyranny it is a must to punish the terrorist -Baba (General) Banda Singh Bahadar Sikhs have only two options: slavery of the Hindus or struggle for their lost sovereignty and freedom -Sirdar Kapur Singh, ICS, MP, MLA and National Professor of Sikhism I am not afraid of physical death; moral death is death in reality Saint-soldier Jarnail Singh Khalsa Martyrdom is our ornament -Bhai Awtar Singh Brahma (General) We do not fear the terrorist Hindu regime.