20200429152003850 Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uptown March 2015.Pdf

MARCH 2015 a publication of the municipal association of south carolina Speaker Jay Lucas, South Carolina House of Representatives Legislative leaders shares priorities he 2015 Hometown Legislative Action Day in February Lucas said this local government experience made him realize focused on hot topics in the General Assembly this year. “we’re all in this together. It’s not a city pothole or a state pothole. T Speaker Jay Lucas kicked off the day by welcoming the The person just wants the pothole fixed.” local officials to Columbia. Lucas recounted his municipal Lucas outlined his priorities for the House this year. experience early in his career. “I have been in the trenches with Transparency and transportation were high on his agenda. you when I worked for the City of Bennettsville as its first finance He specifically discussed legislation requiring public bodies director and got to learn the inner workings of city finance. It to have an agenda for all regularly scheduled meetings. This was a pleasurable and enjoyable experience.” Priorities, page 2 > In This Issue Special Section: Courts and Legal Body-worn cameras Increased efficiency by Frequently asked Expand use of Victims at top of agendas closing donut holes questions: municipal judges Assistance funds Page 7 Page 10 Page 12 Page 14 In this ISSUE Local governments mostly win cell tower Supreme Court case ... 3 57 MEO Institute graduates at HLAD ................... 3 Cities and towns offer smooth sailing for businesses ................. 4 Archiving electronic records ....... 5 Five issues that might protect your House panel (l-r) - Speaker Jay Lucas, Rep. Gary Senate panel (l-r) – Senators Marlon Kimpson, agency from a “Ferguson” ........ -

2020 Silver Elephant Dinner

SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT PRE-RECEPTION SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT GUEST SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT STAFF SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT PRESS SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53RD ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT DINNER • 2020 FTS-SC-RepParty-2020-SilverElephantProgram.indd 1 9/8/20 9:50 AM never WELCOME CHAIRMAN DREW MCKISSICK Welcome to the 2020 Silver Elephant Gala! For 53 years, South Carolina Republicans have gathered together each year to forget... celebrate our party’s conservative principles, as well as the donors and activists who help promote those principles in our government. While our Party has enjoyed increasing success in the years since our Elephant Club was formed, we always have to remember that no victories are ever perma- nent. They are dependent on our continuing to be faithful to do the fundamen- tals: communicating a clear conservative message that is relevant to voters, identifying and organizing fellow Republicans, and raising the money to make it all possible. As we gather this evening on the anniversary of the tragic terrorists attacks on our homeland in 2001, we’re reminded about what’s at stake in our elections this year - the protection of our families, our homes, our property, our borders and our fundamental values. This year’s election offers us an incredible opportunity to continue to expand our Party. -

Tuesday, December 1, 2020 (Organizational Session)

NO. 1 JOURNAL of the HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA REGULAR SESSION BEGINNING TUESDAY, JANUARY 12, 2021 ________ TUESDAY, DECEMBER 1, 2020 (ORGANIZATIONAL SESSION) Tuesday, December 1, 2020 (Organizational Session) Indicates Matter Stricken Indicates New Matter The House assembled at 11:00 a.m. Deliberations were opened with prayer by Rev. Charles E. Seastrunk, Jr., as follows: Our thought for today is from Nahum 1:7: “The Lord is good, a stronghold in the day of trouble; and He knows those who trust in Him.” Let us pray. Almighty God, source of all wisdom and knowledge, guide these women and men in the way of truth and righteousness. Send Your Spirit to keep them in Your love and care. Guide them as they make decisions that will affect both the people of their district and this State. Open their minds and spirit O’ Lord so they are able to absorb all the information they are receiving and use it for the betterment of the lives of others. Bless and keep them, their families, and all of our staff safe and well while they strive to do the state’s business. Lord, in Your mercy, hear our prayers. Amen. Pursuant to Rule 6.3, the House of Representatives was led in the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America by the SPEAKER. MOTION ADOPTED Rep. MCKNIGHT moved that when the House adjourns, it adjourn in memory of Lorenval Donte Evans, which was agreed to. APPOINTMENT OF THE TEMPORARY CHAIRMAN The CLERK of the late House announced that the first order of business is the appointment of a Temporary CHAIRMAN. -

CCAR Supported Candidates Information

PRIMARY2020 RESULTS FROM THE SOUTH CAROLINA ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS® WINNING WITH THE REALTOR® PARTY RPAC is proud to announce that 35 out of our 41 supported state and federal candidates won their primary election. Congratulations to the RPAC supported candidates on their victory! 85% OF SC RPAC SUPPORTED CANDIDATES WON THEIR PRIMARY INCLUDING THOSE WHO WON THEIR RUNOFF INCLUDING 23 SC HOUSE CANDIDATES 16 SC SENATE CANDIDATES A TOTAL OF 35 RPAC SUPPORTED CANDIDATES WON THIER PRIMARY U.S. HOUSE CANDIDATE INCLUDING 1 5 RPAC SUPPORTED CANDIDATES WHO WON THEIR RUNOFF U.S. SENATE CANDIDATE 6 RPAC SUPPORTED CANDIDATES 1 LOST THIER PRIMARY OR RUNOFF CANDIDATE SUCCESS RATE BY STATE/LOCAL/FEDERAL 85% 66% 100% of SC RPAC of SC RPAC of Federal Candidates supported candidates supported candidates supported by SC RPAC in State Races won their in Local Races won their won their primaries. primaries. primaries. PRIMARY WINNERS SUPPORTED BY RPAC SOUTH CAROLINA HOUSE SOUTH CAROLINA SENATE District 5 - Republican District 57 - Democrat District 105 - Republican District 5 - Republican District 18 - Republican District 36 - Democrat ✓ Neal Collins ✓ Lucas Atkinson ✓ Kevin Hardee ✓ Tom Corbin ✓ Ronnie Cromer ✓ Kevin Johnson Incumbant Incumbant Incumbant Incumbant Incumbant Incumbant District 10 - Republican District 68 - Republican District 107 - Republican District 7 - Democrat District 25 - Republican District 39 - Democrat ✓ West Cox ✓ Heather Crawford ✓ Alan Clemmons ✓ Karl Allen ✓ Shane Massey ✓ Vernon Stephens Incumbant Incumbant Incumbant Incumbant -

The General Assembly of South Carolina 124Th Session List of Members

THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF SOUTH CAROLINA 124TH SESSION LIST OF MEMBERS FIRST REGULAR SESSION Convening Tuesday, January 12, 2021 in Columbia (CORRECTED TO DECEMBER 31, 2020) Published by: Charles F. Reid, Clerk South Carolina House of Representatives Members of the 124th General Assembly of South Carolina The Senate 30 Republicans, 16 Democrats, Total 46. All Senators elected in 2020 to serve until Monday after the General Election in November of 2024. Pursuant to Section 2-1-60 of the 1976 Code, as last amended by Act 513 of 1984, Senators are elected from 46 single member districts. [D] after the name indicates Democrat and [R] indicates Republican. Explanation of Reference Marks ✶ Indicates 2020 Senators re-elected . 40 Without previous legislative service (unmarked) . 6 Vacancies . 0 Total Membership 2020-2024 . 46 Information Telephones President's Office . (803) 212-6430 President Pro Tempore Emeritus' Office (111 Gressette Bldg.). (803) 212-6455 Clerk's Office (401 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6200 (1st Floor, State House) . (803) 212-6700 Agriculture & Natural Resources Com. (402 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6230 Banking & Insurance Com. (410 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6240 Bookkeeping (534 Brown Bldg.) . (803) 212-6550 Corrections & Penology Com. (211 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6420 Education Com. (404 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6250 Ethics Com. (205 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6410 Family and Veterans' Services (303 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6320 Finance Com. (111 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6640 Fish, Game & Forestry Com. (305 Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6340 Health Care (Nurse) (511-B Gressette Bldg.) . (803) 212-6175 Interstate Cooperation Com. (213 Gressette Bldg.) . -

Senate Filings March 30.Xlsx

SC ALLIANCE TO FIX OUR ROADS 2020 SENATE FILINGS APRIL 2, 2020 District Counties Served First (MI) Last / Suffix Party Primary Election General Election 1 OCONEE,PICKENS Thomas C Alexander Republican unopposed unopposed 2 PICKENS Rex Rice Republican unopposed unopposed Craig Wooten Republican Richard Cash* (R) Winner of Republican Primary 3 ANDERSON Richard Cash Republican Craig Wooten (R) Judith Polson (D) Judith Polson Democrat Mike Gambrell Republican Mike Gambrell* (R) 4 ABBEVILLE,ANDERSON,GREENWOOD Jose Villa (D) Jose Villa Democrat Tom Corbin Republican Tom Corbin* (R) Winner of Republican Primary 5 GREENVILLE,SPARTANBURG Dave Edwards (R) Michael McCord (D) Michael McCord Democrat Dave Edwards Republican Dwight A Loftis Republican Dwight Loftis* (R) 6 GREENVILLE Hao Wu (D) Hao Wu Democrat Karl B Allen Democrat Karl Allen* (D) Winner of Democratic Primary 7 GREENVILLE Fletcher Smith Democrat Fletcher Smith (D) Jack Logan (R) Jack Logan Republican Ross Turner Republican Ross Turner* (R) 8 GREENVILLE Janice Curtis (R) Janice S Curtis Republican 9 GREENVILLE,LAURENS Danny Verdin Republican unopposed unopposed Floyd Nicholson Democrat Bryan Hope (R) Winner of Republican Primary 10 ABBEVILLE,GREENWOOD,MCCORMICK,SALUDA Bryan Hope Republican Billy Garrett (R) Floyd Nicholson*(D) Billy Garrett Republican Josh Kimbrell Republican Glenn Reese* (D) 11 SPARTANBURG Glenn Reese Democrat Josh Kimbrell (R) Scott Talley Republican Scott Talley*(R) Winner of Republican Primary 12 GREENVILLE,SPARTANBURG Mark Lynch Republican Mark Lynch (R) Dawn Bingham -

Legislative Scorecard a Message from the President Ted Pitts, President & CEO of the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce

2015 LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD A Message From The President Ted Pitts, President & CEO of the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce For many years, the South Carolina body from even debating a comprehensive infrastructure bill Chamber of Commerce has released the on the floor. Simply put, the inability of the Senate to make any annual Legislative Scorecard because our significant progress on the singular issue of this regular session members want to know how their elected left the business community with insufficient results upon which officials voted on issues important to the to gauge the Senate’s performance. As you will note, the 2015 business community. The 2015 Legislative Scorecard designates the Senate’s work as “in-progress” in an effort Scorecard represents votes on the South to highlight the urgency to address the state’s most important Carolina Chamber’s top priorities, our issues upon their return in January 2016 for the second half of this Competitiveness Agenda. We have laid two-year session. The Chamber will score the Senate’s 2015 votes out how your legislators voted on these as part of their 2016 total score. business issues and also recognize our 2015 Business Advocates. As president and CEO, my main priority is to advocate on behalf of you, South Carolina’s business community. With our unified The business community went into 2015 laser focused on two voices, we will continue to drive the pro-jobs agenda in South priorities: workforce development and infrastructure. Our Carolina and work to make this state the best place in the world focus was no accident. -

2018 Primary Results Infographic

HOW DID RPAC DO IN THE SOUTH CAROLINA PRIMARIES? OF RPAC SUPPORTED CANDIDATES 77% WON THEIR PRIMARY ELECTIONS TOTAL CANDIDATE TOTAL CANDIDATES WINS SUPPORTED 43 54 HOW CANDIDATES WERE SUPPORTED 103,000 22,345 8 $53,000 $130,530 18 1 700,007 Direct Mail Phone Calls Polls Total RPAC Total Independent Online Ads Newpaper/ Impressions for Pieces Sent to Voters Conducted Contributions Expendatures Desgined Radio Ad Online Ads ✓ - Won Primary SOUTH CAROLINA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Χ - Lost Primary SUPPORTED BY RPAC * (I) indicates Incumbent District 4 - Republican District 18 - Republican District 32- Republican District 55 - Democrat District 76 - Democrat District 94 - Republican District 101 - Democrat District 112 - Republican ✓ Davey Hiott (I) ✓ Tommy Stringer (I) ✓ R - Max Hyde ✓ Jackie Hayes (I) ✓ Leon Howard (I) ✓ Con Chellis ✓ Cezar McKnight (I) ✓ Mike Sottile (I) Phillip Healy Tony Gilliard R - O’Neal Mintz Archie Scott T’Nae Parker Evan Guthrie Alfred Darby Jason Clouse Jack Scott Glenn Zingarino District 77 - Democrat District 5 - Republican District 21 - Republican District 33- Republican District 62 - Democrat District 98 - Republican District 103 - Democrat District 117 - Republican Χ Joseph McEachern (I) ✓ Neal Collins (I) Χ Phyllis Henderson (I) ✓ Eddie Tallon (I) ✓ Robert Williams (I) John McClenic ✓ Chris Murphy (I) ✓ Carl Anderson (I) ✓ Bill Crosby (I) David Cox Bobby Cox Tommy Dimsdale Joe Ard Kambrell Garvin Larry Hargett John Henry Jordan Scott Pace Alan Quinn Linda Byrd-Spearman Deyaska Spencer Dedric Bonds District -

September 9, 2020 the Honorable Harvey Peeler

September 9, 2020 The Honorable Harvey Peeler The Honorable James H. “Jay” Lucas South Carolina Senate South Carolina House of Representatives Columbia, South Carolina 29201 Columbia, South Carolina 29201 Dear Gentlemen: I am providing for the General Assembly’s consideration the attached recommendations for the Phase II authorization for expenditure of Coronavirus Relief Funds (CRF) from the federal Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. As you are aware, the AccelerateSC task force conducted a thorough review of the CARES Act and made expenditure reimbursement recommendations for COVID-19 prevention efforts and for measures to return our state’s economic engines to full speed. To maximize COVID-19 relief resources available to South Carolinians, the Department of Administration, working with the professional grant management services provider Guidehouse, should determine if state funds appropriated by the General Assembly to state agencies pursuant to Act 116 of 2020 are eligible for federal reimbursement through the CRF in the CARES Act. In order to prevent our state’s small businesses from paying higher taxes to replenish the Unemployment Trust Fund, an additional $450 million should be authorized and made available should the Department of Employment and Workforce request them before the end of this year. In addition, I ask the General Assembly to authorize up to $45 million to be made available in the form of grants to small businesses and non-profit organizations that did not receive federal Paycheck Protection Program loans from the Small Business Administration. This spring, the General Assembly moved quickly to direct funds from the contingency reserve account to the Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) and the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) to address the COVID-19 pandemic. -

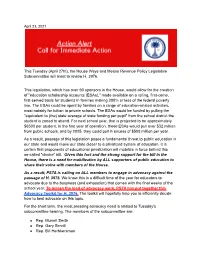

April 23Rd, 2021

April 23, 2021 This Tuesday (April 27th), the House Ways and Means Revenue Policy Legislative Subcommittee will meet to review H. 3976. This legislation, which has over 60 sponsors in the House, would allow for the creation of "education scholarship accounts (ESAs)," made available on a rolling, first-come, first-served basis for students in families making 200% or less of the federal poverty line. The ESAs could be spent by families on a range of education-related activities, most notably for tuition to private schools. The ESAs would be funded by pulling the "equivalent to (the) state average of state funding per pupil" from the school district the student is zoned to attend. For next school year, that is projected to be approximately $6500 per student. In the first year of operation, these ESAs would pull over $32 million from public schools, and by 2025, they could pull in excess of $500 million per year. As a result, passage of this legislation poses a fundamental threat to public education in our state and would move our state closer to a privatized system of education. It is certain that proponents of educational privatization will mobilize in force behind this so-called "choice" bill. Given this fact and the strong support for the bill in the House, there is a need for mobilization by ALL supporters of public education to share their voice with members of the House. As a result, PSTA is calling on ALL members to engage in advocacy against the passage of H. 3976. We know this is a difficult time of the year for educators to advocate due to the busyness (and exhaustion) that comes with the final weeks of the school year. -

2020 SC Senate and House Primary Races SC Congressional Races Ballot Questions

2020 SC Senate and House Primary Races SC Congressional Races Ballot Questions Projected Winners Highlighted Below ** Runoff SC Senate Primary Races Name District Primary Opposition Republicans Sen. Richard Cash 56.76% District 3, Anderson Craig Wooten (R) Sen. Tom Corbin 70.37% District 5, Spartanburg Dave Edwards (R) Sen. Ross Turner 68.20% District 8, Greenville Janice Curtis (R) Sen. Scott Talley 52.82% District 12, Greenville, Mark Lynch (R) Spartanburg Sen. Ronnie Cromer 62.14% District 18, Lexington, Charles Bumgardner (R) Newberry, Union Sen. Shane Massey 78.84% District 25, Aiken, Edgefield, Susan Swanson (R) Lexington, McCormick, Saluda Sen. Luke Rankin 40.19% ** District 33, Horry County John Gallman (R) 34.42% ** Carter Smith (R) Sen. Sandy Senn District 41, Charleston Jason Mills (D) Sam Skardon (D)63.04% Democrats Sen. Karl Allen 70.12% District 7, Greenville Fletcher Smith (D) Sen. Floyd Nicholson District 10, Greenwood Billy Garrett (R) Bryan Hope (R) Sen. Mike Fanning 67.93% District 17, Chester, Fairfield, Mary Gail Douglas (D) York Sen. Dick Harpootlian District 20, Richland Randy Dickey (R) Benjamin Dunn (R) 71.52% Sen. Mia McCleod District 22, Richland Lee Blatt (R) 76.26% David Larson (R) Sen. Nikki Setzler District 26, Lexington Perry Finch (R) Chris Smith (R) 68.79% Sen. Gerald Malloy District 29, Marlboro JD Chaplin (R) 82.40% Ronald Reese Page (R) Sen. Kent Williams 76.73% District 30, Dillon, Florence, Patrick Richardson (D) Horry Marion, Marlboro Sen. Ronnie Saab 71.22% District 32, Berkeley, Manley Collins (D) Florence, Georgetown, Horry, Kelly Spann (D) Williamsburg Ted Brown (D) Sen. -

Table of Contents

ELECTION REPORT 2008 Prepared and published by the S.C. State Election Commission May 2009 www.scvotes.org 1 1. COMMISSIONERS AND STAFF ..................................................................................4 2. COUNTY ELECTION COMMISSION DIRECTORY .....................................................5 3. COUNTY VOTER REGISTRATION DIRECTORY........................................................7 4. CERTIFIED POLITICAL PARTIES OF SC...................................................................9 5. SPECIAL ELECTIONS ...............................................................................................10 5.1 STATE SENATE DISTRICT 46 (BEAUFORT).................................................................10 5.1.1 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY – May 1, 2007 .........................................................10 5.1.2 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY RUNOFF – May 15, 2007 .......................................10 5.1.3 SPECIAL ELECTION – June 19, 2007.............................................................10 5.2 STATE SENATE DISTRICT 44 (BERKELEY) .................................................................11 5.2.1 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY – June 19, 2007 ......................................................11 5.2.2 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY RUNOFF – July 3, 2007..........................................11 5.2.3 SPECIAL ELECTION – August 7, 2007 ...........................................................11 5.3 STATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT 124 (BEAUFORT) .............................12 5.3.1 REPUBLICAN PRIMARY – September 4,