September 24, 2008 SENT VIA FACSIMILE and CERTIFIED MAIL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Park Science 19(1): Arctic Alaska Are Living at the Species’ Northern-Most to Identify Habitats Most Frequented by Bears and 4-9

National Park Service US Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Region 11, Alaska Below the Surface Fish and Our Changing Underwater World Volume 19, Issue 1 Noatak National Preserve Cape Krusenstern Gates of the Arctic Alaska Park Science National Monument National Park and Preserve Kobuk Valley Volume 19, Issue 1 National Park June 2020 Bering Land Bridge Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Preserve Denali National Wrangell-St Elias National Editorial Board: Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Leigh Welling Debora Cooper Grant Hilderbrand Klondike Gold Rush Jim Lawler Lake Clark National National Historical Park Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Park and Preserve Guest Editor: Carol Ann Woody Kenai Fjords Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Katmai National Glacier Bay National National Park Design: Nina Chambers Park and Preserve Park and Preserve Sitka National A special thanks to Sarah Apsens for her diligent Historical Park efforts in assembling articles for this issue. Her Aniakchak National efforts helped make this issue possible. Monument and Preserve Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Below the Surface: Fish and Our Changing Environmental DNA: An Emerging Tool for Permafrost Carbon in Stream Food Webs of Underwater World Understanding Aquatic Biodiversity Arctic Alaska C. -

Appendix C.5-California Red Legged Frog Report

Appendix C: Biological Resources PROTOCOL-LEVEL CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG SURVEY REPORT FOR THE FORMER SAN LUIS OBISPO TANK FARM SITE (TANK FARM) SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: CHEVRON ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT COMPANY December 2008 C.5-1 Chevron Tank Farm EIR Appendix C: Biological Resources Chevron Tank Farm Site California Red-Legged Frog Survey Report Project No. 0601-3281 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................... 1 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION.................................................... 1 3.0 PROJECT SITE SETTING................................................................................ 1 3.1 EAST BRANCH OF SAN LUIS OBISPO CREEK ................................. 2 3.2 FRESHWATER MARSH ....................................................................... 2 3.3 SEASONAL WET MEADOW................................................................. 3 4.0 CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG LIFE HISTORY....................................... 3 5.0 SURVEY METHODOLOGY .............................................................................. 4 6.0 CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG LITERATURE REVIEW.......................... 5 7.0 FIELD SURVEY RESULTS............................................................................... 7 8.0 CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG PREDATOR CONTROL......................... 10 9.0 CONCLUSION .................................................................................................. 10 -

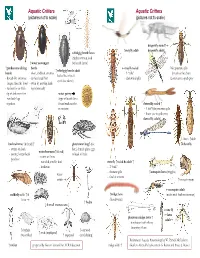

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Habitat Use of Amphibians in Southeast Alaska

Discovery Southeast Founded in 1989 in Juneau and serving communities throughout Southeast Alaska, Discovery Southeast is a nonprofit organization that promotes direct, hands-on learning from nature through natural science and outdoor education programs for youth and adults, students and teachers. Discovery Southeast naturalists aim to deepen the bonds between people and nature. (907) 463-1500 fax 463-1587 [email protected] www.discoverysoutheast.org PO Box 21867 Juneau, AK 99802 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 2 1 Methods ....................................................................................................... 5 Initial pond mapping with GIS and photointerpretation ................................ 5 Selection of study ponds ............................................................................. 6 Pond habitat assessments .......................................................................... 8 Amphibian surveys .....................................................................................10 Temperature loggers ..................................................................................13 Atlas of SE Alaskan amphibian records ....................................................15 2 Juneau area breeding pond survey .........................................................17 3 Aquatic vegetation ....................................................................................21 Submerged .................................................................................................21 -

'Handedness' in the Pacific Tree Frog (Hyla Regilla)

1926 CAN. J. ZOOL. VOL. 55, 1977 JAIRAJPURI, M. S. 1971. On Scutylenchus mamillatus lonolaimidae n.rank. Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 37: (Tobar-Jimenez, 1966) n.comb. Natl. Acad. Sci., India, 68-77. 40th Session, Feb. Vol. 18. Wu, L.-Y. 1969. Three new species of genus Tylen- SIDDIQI,M. R. 1970. On the plant-parasitic nematode gen- chorhynchus Cobb, 1913 (Tylenchidae: Nematoda)from era Merlinius gen.n. and Tylenchorhynchus Cobb and Canada. Can. J. Zool. 47: 563-567. the classification of the families Dolichodoridae and Be- 'Handedness' in the Pacific tree frog (Hyla regilla) LAWRENCEM. DILL Department ofBiologica1 Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, B.C., Canada V5A IS6 Received May 9, 1977 DILL,L. M. 1977. 'Handedness' inthe Pacific treefrog(Hy1a regilla). Can. J. Zool. 55: 1926-1929. The jumping directions of 24 individual Pacific tree frogs (Hyla regilla), in response to repeated presentations of a model predator, were recorded. The mean jump angle was 70" from the frog's initial bearing regardless of whether the jump was to the left or the right. There was a slight bias within the sample towards left jumps, and most frogs had longer right than left hindlimbs. Some individual frogs jumped preferentially to the left, indicating the existence of 'handedness' in this species. DILL,L. M. 1977. 'Handedness' inthe Pacific tree frog (Hylaregilla). Can. J. Zool. 55: 1926-1929. Vingt-quatre grenouilles arboricoles Hyla regilla ont ete soumises a la presence repetee d'un leurre de predateur; on a note chaque fois ladirectiondu saut defuite. L'angle moyendu saut est a 70" de la position initiale, que ce saut soit vers la droite ou vers la gauche. -

Survey for CA Red-Legged Forg at Site, W/Contact Rpt 11/20/95

APPENDIX E SDMSDocID 2003220 Survey for California Red-legged Frog (Rana aurora draytotiii) at the Lava Cap Mine Project Bechtel Project 22447-261-020 Report prepared bj Roy A. Woodward. Ph.D August 1995 Introduction The Lava Cap Mine site is within the historic range of the California red-legged frog (Rana aurora draytonn) (referred to herein as 'red-legged frog', scientific names follow Robert C Stebbms. Western Reptiles and Amphibians, 1985), a species proposed for listing on the federal endangered species list In order to ascertain the presence/absence of the species at the Lava Cap Mine site, a survey was conducted on July 27 and 28, 1995 by Bechtel biologist Roy Woodward and Bechtel site leader Tom Jenoho Methods Prior to beginning the field survey a literature search was conducted at the University of California, Santa Cruz to obtain pertinent information about red-legged frog behavior and taxonomv Also, interviews were held with recogni7ed frog experts Dr Robert Fisher University of California San Diego, and Dr Mark Jennings U S Biological Survey in Davis, California It was determined from the literature and interviews that the vicinity of the Lava Cap Mine site was at one time inhabited b) red legged frogs, but there have been no reliable reports of the species in this area of the Sierra Nevada foothills for over thirty years Red-legged frogs have become rare throughout California as a result of habitat degradation, over-harvesting by humans for frog legs and competition from exotic amphibians such as bullfrogs Dr Jennings and -

Biology 2 Lab Packet for Practical 4

1 Biology 2 Lab Packet For Practical 4 2 CLASSIFICATION: Domain: Eukarya Supergroup: Unikonta Clade: Opisthokonts Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata – Chordates Subphylum: Urochordata - Tunicates Class: Amphibia – Amphibians Subphylum: Cephalochordata - Lancelets Order: Urodela - Salamanders Subphylum: Vertebrata – Vertebrates Order: Apodans - Caecilians Superclass: Agnatha Order: Anurans – Frogs/Toads Order: Myxiniformes – Hagfish Class: Testudines – Turtles Order: Petromyzontiformes – Lamprey Class: Sphenodontia – Tuataras Superclass: Gnathostomata – Jawed Vertebrates Class: Squamata – Lizards/Snakes Class: Chondrichthyes - Cartilaginous Fish Lizards Subclass: Elasmobranchii – Sharks, Skates and Rays Order: Lamniiformes – Great White Sharks Family – Agamidae – Old World Lizards Order: Carcharhiniformes – Ground Sharks Family – Anguidae – Glass Lizards Order: Orectolobiniformes – Whale Sharks Family – Chameleonidae – Chameleons Order: Rajiiformes – Skates Family – Corytophanidae – Helmet Lizards Order: Myliobatiformes - Rays Family - Crotaphytidae – Collared Lizards Subclass: Holocephali – Ratfish Family – Helodermatidae – Gila monster Order: Chimaeriformes - Chimaeras Family – Iguanidae – Iguanids Class: Sarcopterygii – Lobe-finned fish Family – Phrynosomatidae – NA Spiny Lizards Subclass: Actinistia - Coelocanths Family – Polychrotidae – Anoles Subclass: Dipnoi – Lungfish Family – Geckonidae – Geckos Class: Actinopterygii – Ray-finned Fish Family – Scincidae – Skinks Order: Acipenseriformes – Sturgeon, Paddlefish Family – Anniellidae -

1 CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens

CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens List updated November 2019 0-CWU-Collection-List.docx Specimens collected primarily from North American mid-continent and coastal Alaska for zooarchaeological research and teaching purposes. Curated at the Zooarchaeology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University, under the direction of Dr. Pat Lubinski, [email protected]. Facility is located in Dean Hall Room 222 at CWU’s campus in Ellensburg, Washington. Numbers on right margin provide a count of complete or near-complete specimens in the collection. Specimens on loan from other institutions are not listed. There may also be a listing of mount (commercially mounted articulated skeletons), part (partial skeletons), skull (skulls), or * (in freezer but not yet processed). Vertebrate specimens in taxonomic order, then invertebrates. Taxonomy follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System online (www.itis.gov) as of June 2016 unless otherwise noted. VERTEBRATES: Phylum Chordata, Class Petromyzontida (lampreys) Order Petromyzontiformes Family Petromyzontidae: Pacific lamprey ............................................................. Entosphenus tridentatus.................................... 1 Phylum Chordata, Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes) unidentified shark teeth ........................................................ ........................................................................... 3 Order Squaliformes Family Squalidae Spiny dogfish ........................................................ -

Amphibians in Managed Woodlands: Tools for Family Forestland Owners

Woodland Fish & Wildlife • 2017 Amphibians in Managed Woodlands Tools for Family Forestland Owners Authors: Lauren Grand, OSU Extension, Ken Bevis, Washington Department of Natural Resources Edited by: Fran Cafferata Coe, Cafferata Consulting Pacific Tree (chorus) Frog Introduction good indicators of habitat quality (e.g., Amphibians are among the most ancient habitat diversity, habitat connectivity, water vertebrate fauna on earth. They occur on all quality). Amphibians also play a key role in continents, except Antarctica, and display a food webs and nutrient cycling as they are dazzling array of shapes, sizes and adapta- both prey (eaten by fish, mammals, birds, tions to local conditions. There are 32 species and reptiles) and predators (eating insects, of amphibians found in Oregon and Wash- snails, slugs, worms, and in some cases, ington. Many are strongly associated with small mammals). The presence of forest freshwater habitats, such as rivers, streams, salamanders has also been positively cor- wetlands, and artificial ponds. While most related to soil building processes (Best and amphibians spend at least part of their life- Welsh 2014). cycle in water, some species are fully terres- Landowners can promote amphib- trial, spending their entire life-cycle on land ian habitat on their property to improve or in the ground, generally utilizing moist overall ecosystem health and to support areas within forests (Corkran and Thoms the species themselves, many of which 2006, Leonard et. al 1993). have declining or threatened populations. The following sections of this publica- Photo by Kelly McAllister. Amphibians are of great ecological impor- tance and can be found in all forest age tion describe amphibian habitats, which classes. -

Call of the Chorus Frog: an Undergraduate Experience in Field Research in the Elwha River Basin

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Call of the Chorus Frog: An Undergraduate Experience in Field Research in the Elwha River Basin Nicole VandePutte Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation VandePutte, Nicole, "Call of the Chorus Frog: An Undergraduate Experience in Field Research in the Elwha River Basin" (2020). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 388. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/388 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Call of the Chorus Frog By Nicole VandePutte By the light of our headlamps, we hiked once more towards the ponds deep in the forest. Our group traveled in silence. The only sounds heard were those of our footsteps and the rushing of the Elwha River in the distance. We had traversed these trails countless times in the past two weeks, but night had a way of making the forest unfamiliar. Luckily, my fellow researchers Sverre and Nora have an impeccable sense of direction, so I followed their lead. Soon, from a distance, we heard the chorus of frogs. The group collectively paused. We turned off our headlamps, and continued in utter darkness as quietly as possible. Caution was paramount. -

Report on Diamond Lake Post-Rotenone Amphibian Assessment, 2007-2009

2007-2009 Diamond Lake Amphibian Assessment By Chris Rombough 31 December 2009 Summary Amphibian surveys of Diamond Lake and surrounding areas were conducted from 2007-2009, following a 2006 rotenone treatment of the lake. Data collected during this study indicates that populations of all amphibian species (except for rough-skinned newt) have increased since 2007. The effects of rotenone in establishing 2007 amphibian population sizes are not completely known, but were probably greatest on the northwestern salamanders and rough-skinned newts inhabiting the lake. Population sizes of the remaining amphibian species (Cascades frog, Pacific tree frog, western toad, and long-toed salamander) are probably less affected by rotenone treatment of the lake than the two aforementioned salamanders. Survey data indicate that aquatic areas away from Diamond Lake are more important to these species than the lake itself, and that physical factors such as annual precipitation may play a greater role in structuring their populations than any treatment of the lake. Part 1. 2009 Amphibian Sampling Introduction The 2009 amphibian sampling results for both spring and fall surveys are reported here. The format follows that of previous reports (e.g., Hayes and Price 2007, Hayes and Rombough 2008), with the exception that the number and distribution of amphibian captures are summarized for each area surveyed, rather than simply reporting catch per unit effort. There are two reasons for this. First, catch or observation of amphibians during visual surveys varies tremendously as a function of many factors, including time, weather, and surveyor capacity. In the case of this report, where data from multiple surveyors with varying degrees of skill are combined, a more informative metric than catch per unit effort are changes in the patterns of distribution, relative abundance, and life stages of amphibians observed across the survey areas. -

Coastal Tailed Frog Ascaphus Truei

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Coastal Tailed Frog Ascaphus truei in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Coastal Tailed Frog Ascaphus truei in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 53 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog Ascaphus montanus and the Coast Tailed Frog Ascaphus truei in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 30 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Dupuis, L.A. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the on the Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog Ascaphus montanus and the Coast Tailed Frog Ascaphus truei in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-30 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Linda Dupuis for writing the status report on the Coastal Tailed Frog (Ascaphus truei) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Ronald J. Brooks and Kristiina Ovaska, Co-chairs of the COSEWIC Amphibians and Reptiles Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Grenouille-à-queue côtière (Ascaphus truei) au Canada.