A Lighter Shade of Green: Reproducing Nature in Central Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disney's Contemporary Resort

WALT DISNEY WORLD DELUXE RESORT DISNEY’S CONTEMPORARY RESORT Disney’s Contemporary Resort Some images do not represent current operational guidelines or health and safety measures, such as face coverings. Some locations, experiences, and services may be modified or unavailable, may have limited capacity and may be subject to limited availability or even closure. Visit disneytraveltradeinfo.com/wdwresorthotels for important details. Retreat to this ultra-modern Disney Resort hotel and discover award-winning dining, spectacular views and dazzling pools. Whether you’re staying in the iconic A-frame ROOMS AT A GLANCE Contemporary tower or the nearby Garden Wing, you can walk to Magic Kingdom® Park 1000+ Guest Rooms main gate or catch the monorail as it breezes through the tower. Inside a 90-foot-tall 428 Villas 633 Deluxe Rooms mural by Disney Legend Mary Blair—responsible for the distinct look and feel of the “it’s a 23 Suites small world” attraction—celebrates the Grand Canyon and the American Southwest. ® sleeps up to four Guests, 4+1 plus one child under age 3 in a crib Standard Rooms 2 queen-size beds & 1 single day bed or 1 king-size bed & 1 single day bed Club Level Guests choosing Club Level accommodations Standard Room at the Tower Club or Atrium Club receive personalized concierge service and lounge with continental breakfast, midday snacks and evening wine, hors d’oeuvres, cordials and desserts. TRANSPORTATION Bus Service to Walt Disney World® Resort Theme Parks, Water Parks Typical Standard Room Parking & Landscaping View, with 1 king-size bed and 1 single day bed or 2 California Grill and Disney Springs® queens and 1 single day bed, 437 sq. -

The Disney Bloodline

Get Your Free 150 MB Website Now! THE SKILL OF LYING, THE ART OF DECEIT The Disney Bloodline The Illuminati have refined the art of deception far beyond what the common man has imagined. The very life & liberty of humanity requires the unmasking of their deceptions. That is what this book is about. Honesty is a necessary ingredient for any society to function successfully. Deception has become a national pastime, starting with our business and political leaders and cascading down to the grass roots. The deceptions of the Illuminati's mind-control may be hidden, but in their wake they are leaving tidal waves of distrust that are destroying America. While the CIA pretend to have our nations best interest at heart, anyone who has seriously studied the consequences of deception on a society will tell you that deception will seriously damage any society until it collapses. Lies seriously damage a community, because trust and honesty are essential to communication and productivity. Trust in some form is a foundation upon which humans build relationships. When trust is shattered human institutions collapse. If a person distrusts the words of another person, he will have difficulty also trusting that the person will treat him fairly, have his best interests at heart, and refrain from harming him. With such fears, an atmosphere of death is created that will eventually work to destroy or wear down the cooperation that people need. The millions of victims of total mind- control are stripped of all trust, and they quietly spread their fears and distrust on a subconscious level throughout society. -

Discover the Sophisticated Side of Walt Disney World® Resort

DISCOVER THE SOPHISTICATED SIDE OF WALT DISNEY WORLD® RESORT Is it possible for sophisticated travelers to really enjoy themselves in the land of Mickey Mouse? Absolutely! Walt Disney World Resort has undergone an amazing transformation with an abundance of fantastic themed resorts and sumptuous dining choices. Maybe your image of Disney is of lackluster, motel-style accommodations. Not so! All of Disney’s Deluxe Resort choices are unique and offer that special Disney touch. You’ll find them to be adorned with impressive lobbies, painstakingly landscaped grounds, first-rate restaurants, elaborately themed pools, and gracious accommodations. All offer top-notch recreational facilities and services. In fact it can be quite difficult to choose which fantasy you wish to indulge. Let me tell you about my favorites: v Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort & Spa, with its red-gabled roofs and Victorian elegance, draws inspiration from the grand Florida seaside “palace hotels” of 19th- century America’s Gilded Age. Just a short monorail ride to the Magic Kingdom®, it spreads along the shore of the Seven Seas Lagoon with spectacular views of Cinderella Castle and the Wishes fireworks show. Aquatic enticements include a crescent white sand beach dotted with brightly striped, canopied lounge chairs, a large sophisticated pool in the central courtyard, a new beachside Florida springs-style pool, and a classy marina sporting a wide assortment of watercraft. A full service health club and spa, tennis courts, 5 restaurants, two lounges, and sophisticated shopping round out the list of exceptional offerings. v A navy blue blazer should be in order for a stay at Disney’s Yacht Club Resort where guests find the sophisticated ambience of a posh Eastern seaboard hotel of the 1880s. -

Disney's Grand Floridian Resort &

WALT DISNEY WORLD DELUXE RESORT DISNEY’S GRAND FLORIDIAN RESORT & SPA Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort & Spa Some images do not represent current operational guidelines or health and safety measures, such as face coverings. Some locations, experiences, and services may be modified or unavailable, may have limited capacity and may be subject to limited availability or even closure. Visit disneytraveltradeinfo.com/wdwresorthotels for important details. Victorian elegance meets modern sophistication at this lavish bayside Resort hotel. Relax in the sumptuous lobby as the live orchestra plays ragtime, jazz and popular Disney ROOMS AT A GLANCE tunes. Bask on the white-sand beach, indulge in a luxurious massage and watch the 850+ Guest Rooms fireworks light up the sky over Cinderella Castle. Just one stop to Magic Kingdom Park 100 Villas ® 24 Suites on the complimentary Resort Monorail, this timeless Victorian-style marvel evokes Palm Beach’s golden era. sleeps up to five Guests, 5+1 plus one child under age 3 in a crib Standard Rooms 2 queen-size beds & 1 single day bed or 1 king-size bed and 1 queen sleeper sofa or 1 king bed Club Level Guests choosing Club Level accommodations at the Royal Palm Club receive personalized concierge service and lounge with continental Standard Room breakfast, midday snacks and evening wine, hors d’oeuvres, cordials and desserts. TRANSPORTATION Bus Service to Walt Disney World® Resort Theme Parks, Water Parks and Disney Springs Typical Standard Room Garden, Pool and Marina View, with two queen beds and one single ® day bed, one king bed and one queen sleeper sofa or one king bed, and a private patio or 1900 Park Fare balcony. -

Westgate Resorts Look What's FREE at Walt Disney World Resort

WestgateReservations.com $5.95 Westgate Resorts Insider’s Guide Walt Disney World Resort Look what’s FREE at Walt Disney World Resort WestgateReservations.com INSIder’s GuIDE | Walt Disney Wold Resort Disney Insider’s Guide Look what’s FREE at Walt Disney World Resort From travel expenses and theme This Insider’s Guide to Walt park tickets to souvenirs, accom- Disney World Resort is your modations and meals, the costs source for big savings and big of a Walt Disney World vacation fun in and around Walt Disney can add up quickly. Yet when it World Resort! comes to creating a magical and memorable Disney World vaca- Make the most of your Disney tion for your family, there are a World vacation by making the wide variety of fun options that most of the following 10 free are absolutely free! activities. WestgateReservations.com INSIder’s GuIDE | Walt Disney Wold Resort Hunt for Hidden Mickeys Disney World offers a massive playground for playing “I Spy.” All PhotoS By JAIme RuffneR Disney’s Imagineers Simple have created visit the a long-running front desk of tradition of the resort and incorporating hidden ask for a paper Mickey Mouse head that outlines the hunt silhouettes into their and offers clues. You can designs and construction Mickey Mouse silhouette spend a couple hours of throughout Disney’s in plain sight. The concept fun exploring the beautiful theme parks, resorts and quickly became a tradition hotel while searching for other areas. and today Disney fans the elusive hidden mouse endlessly search for silhouettes. If you’re The Hidden Mickey hidden Mickeys in theme searching in the vicinity concept originally started parks, hotels and even in of Bay Lake, near one of as an inside joke among Disney movies. -

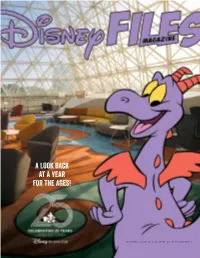

A Look Back at a Year for the Ages!

A LOOK BACK AT A YEAR FOR THE AGES! winter 2016 • Volume 25 • Number 4 I recently met some seasoned travelers who treat Walt Disney World Resorts as second homes, returning year after year and passing down their vacation traditions from generation to generation. They receive world-class service from dedicated Cast Members despite no cash changing hands at the end of their stay, and while they’re here, they make a lot of babies. Wait, you thought I was talking about Members? Sorry, I should’ve clarified. I’m talking about birds – purple martins, to be specific. Each year, these agile aerial acrobats fly more than 3,000 miles from the Brazilian Amazon to Walt Disney World Resort, where they settle into specially created accommodations perched on pedestals before finding mates and…well…you know the rest. You can learn more about these curious creatures through the latest installment of our “Quiz Ed” feature on pages 7-8. I mention the birds here because, like many stories in the pages ahead, theirs is as much about where they’re going as where they’ve been. Our community hasn’t just celebrated the past 25 years in 2016; we’ve celebrated 25 years and beyond. So where does Membership Magic go in that great “beyond?” For starters, it sees some of the most popular elements of our 25th anniversary celebration continue in the New Year (pages 3-4), it sees Members sail the Rhine in distinctive fashion (pages 5-6) and it sees one of the most beloved resorts in our neighborhood blaze new trails through the wilderness (page 9). -

The Best of the Best of Walt Disney World Resorts

The Best of the Best of Walt Disney World Resorts Best Resort Pools Disney’s Yacht and Beach Resort’s Club’s Storm-along Bay, a three- acre miniature water park; the Nanea Volcano Pool at Disney’s Polynesian Resort with its luxuriant waterfall, smoking peak, and perfect views of Cinderella Castle; and the boulder-strewn Silver Creek Springs Pool at Disney’s Wilderness Lodge with its own erupting geyser. Best Deluxe Resort On Disney property it’s Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort & Spa’s public areas with its upscale Victorian ambience and lagoon side setting facing the Magic Kingdom® (guest rooms here need a redo, something that is scheduled to early 2014). Off-property it is the Waldorf Astoria Orlando where you may be tempted never to leave the resort. And stay tuned for the new Four Seasons Resort Orlando at Walt Disney World Resort, sure to be tops on this list! Best Disney Deluxe Villa Resort The Villas at Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort & Spa, the newest Disney Deluxe Villa Resort in its repertoire. Second runner up is Bay Lake Tower at Disney’s Contemporary Resort with is hip, modern look, monorail access, and spectacular views of the Magic Kingdom. Best Atmosphere Disney’s Animal Kingdom Lodge, where hundreds of animals roam the savanna and the air is pulsating to the beat of African drums. Best Lobby How to choose? Three make the cut: Disney’s Wilderness Lodge, Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort & Spa, and Disney’s Animal Kingdom Lodge, all eye-popping in their grandeur. Best Access to the Parks Disney’s Contemporary Resort with not only monorail access to the Magic Kingdom but a walking path as well. -

Magic Kingdom Park Resort Area

MAGIC KINGDOM PARK RESORT AREA DISNEY’S GRAND FLORIDIAN RESORT & SPA DISNEY’S POLYNESIAN VILLAGE RESORT DISNEY’S WILDERNESS LODGE DISNEY’S FORT WILDERNESS RESORT & CAMPGROUND DISNEY’S CONTEMPORARY RESORT WALT DISNEY WORLD DELUXE RESORT DISNEY’S GRAND FLORIDIAN RESORT & SPA Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort & Spa Victorian elegance meets modern sophistication at this lavish bayside Resort hotel. Relax in the sumptuous lobby as the live orchestra plays ragtime, jazz and popular Disney ROOMS AT A GLANCE tunes. Bask on the white-sand beach, indulge in a luxurious massage and watch the 850+ Guest Rooms fi reworks light up the sky over Cinderella Castle. Just one stop to Magic Kingdom Park 100 Villas ® 24 Suites on the complimentary Resort Monorail, this timeless Victorian-style marvel evokes Palm Beach’s golden era. sleeps up to fi ve Guests, 5+1 plus one child under age 3 in a crib Standard Rooms 2 queen-size beds & 1 single day bed or 1 king-size bed and 1 queen sleeper sofa or 1 king bed Club Level Guests choosing Club Level accommodations at the Royal Palm Club receive personalized concierge service and lounge with continental Standard Room breakfast, midday snacks and evening wine, hors d’oeuvres, cordials and desserts. TRANSPORTATION Bus Service to Walt Disney World® Resort Theme Parks, Water Parks and Disney Springs Typical Standard Room Garden, Pool and Marina View, with two queen beds and one single ® day bed, one king bed and one queen sleeper sofa or one king bed, and a private patio or 1900 Park Fare balcony. 448 sq. -

Simulation of Runoff and Water Quality for 1990 and 2008 Land-Use Conditions in the Reedy Creek Watershed, East-Central Florida

Simulation of Runoff and Water Quality for 1990 and 2008 Land-Use Conditions in the Reedy Creek Watershed, East-Central Florida U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4018 Prepared in cooperation with the Reedy Creek Improvement District Cover photographs by Eddie Snell, Reedy Creek Improvement District, Florida. Simulation of Runoff and Water Quality for 1990 and 2008 Land-Use Conditions in the Reedy Creek Watershed, East-Central Florida By Shaun M. Wicklein and Donna M. Schiffer U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02–4018 Prepared in cooperation with the Reedy Creek Improvement District Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey, WRD U.S. Geological Survey Suite 3015 Branch of Information Services 227 North Bronough Street Box 25286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the Internet at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Walt Disney World Resort

confidence character courage &+:' " Badges at the ® Resort. !" #$%"&'(#( ""("&"(" "(!#'!)( *!")!"!"$ +)!#!!''&)& ")- !® Resort! !"-' '!®!"$"! _ bug at +"1"®(!) '"2! _ 3 at Epcot®(" 4)®"#)!3# _ (!(231"® Park !!7 8!!$")! (!#''&!)#)! '"""$ Use this handbook to get inspired and see the options available to !$!!" _ these should serve as a visual guide !#)!#$ )!)'9!'!7 Special Thanks to the Girl Scouts of Citrus! ©Disney GS2012-6811 = 31" = Epcot ® Park ® = 4 ) = +"1" ® = ® Park ® Resort Daisies Lupe - Honest & Fair Become an apprentice sorcerer and set off on a quest to stop the Disney Villains from taking over the Magic Kingdom Park, as you play Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom. Magic spells in the form of special cards will lead you to the Villains’ hiding places. Share your cards with friends and take turns defeating the Villains to help save the park. Sunny - Friendly & Helpful Take a moment to chat with a Disney Cast Member about their job at the Walt Disney World Resort. They will enjoy sharing some Disney magic with you! Zinni - Considerate and Caring Create a souvenir Duffy the Disney Bear cut-out as you visit the Kidcot Fun Stops located throughout World Showcase in Epcot. Swap your Duffy with a fellow Girl Scout at different locations and take turns coloring and drawing to observe each person’s creativity. Once you’re done, share your Duffy with a friend. Tula - Courageous and Strong Catch the fun-filled, dream-inspired musical stage show, Dream Along With Mickey at the Magic Kingdom Park. Observe how your favorite Disney Characters are courageous and strong. For instance, Peter Pan displays courage when he accepts Captain Hook’s challenge. -

Walt Disney World® Resort Wow Experiences!

WALT DISNEY WORLD® RESORT WOW EXPERIENCES! So many things at Walt Disney World seem special, but a handful of experiences really take the cake. Plan on at least one or two of the following excursions to make your stay extra-unique, a memory to last a lifetime. Swim with the Sharks Take the ultimate dive in Epcot’s 5.7-million-gallon aquarium at The Seas with Nemo & Friends with more than 65 species of marine life, including sharks, turtles, eagle rays, and diverse tropical fish. With DiveQuest you become part of the show and enjoy guaranteed calm seas, no current, and unlimited visibility. Even more fun, your family and friends can view your dive through the aquarium’s giant acrylic windows. Guests must be at least 10 years of age and provide proof of SCUBA certification to participate. $175. Call 407/WDW- TOUR for information. Catch a Wave If the ocean is a bit too intimidating, learn to “Hang 10” from the experts in a safe and controlled environment at Typhoon Lagoon with waves up to six feet and up to four rounds of surfing. Lessons begin before park opening hours so guests must furnish their own transportation to the park since buses are not up and running quite so early in the morning. Offered Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday for $150. Participants must be at least eight years old and strong swimmers. Maximum of thirteen people per class with surfboards provided. Call (407) WDW-PLAY or (407) 939-7529 for reservations. Celebrate Your Special Day Step aboard a pontoon boat for an especially memorable birthday cruise around Disney’s waterways complete with driver, bag snacks, and beverages. -

WDW Bay Lake

The Intentional Traveler’s Guide To Walt Disney World THE INTENTIONAL TRAVELER • INTEND2TRAVEL.COM • DEC 2019 Insider Tips On How To Get The Most Out Of Your Walt Disney World Vacation WDW Bay Lake & Seven Seas Lagoon Selecting Your WDW has an impact on how on the shores of the you get to the parks and lagoon: Vacation Neighborhood what other entertainment options The Contemporary Walt Disney World are nearby. At the time Resort – An ultra Neighborhoods: Bay Lake & of the Disney World modern, multi-story A- Seven Seas Lagoon grand opening there Frame hotel with the were only two of these monorail gliding neighborhood areas, through its' center. It is Seven Seas Lagoon and located on the lake, Lake Buena Vista near the channel that Shopping Village. connects Seven Seas Lagoon with the larger Even today, just as it Bay Lake. In addition to was forty-five years ago, Seven monorail service there are also Seas Lagoon is the center of motor launches that will take attention. People driving in to guests to the park entrance. visit The Magic Kingdom, once they park, first experience The Polynesian Resort – Built crossing the lagoon. At the on the tradition of Polynesian Transportation Center, visitors great houses, it sits on the shore can cross the water on a New of the lagoon and has a monorail York City style ferry or a station at its' front door that will smaller motor launch or they take you to The Magic can ride a monorail that Kingdom. At the park monorail continuously circles the lagoon stop you can also switch to the Inside Disney World Florida transporting them to The Magic Epcot monorail.