Guidelines for Preparation of Integrated Transport Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icomera Delivers Onboard Entertainment System for Transwa's

Press release 19th November 2020 Icomera Delivers Onboard Entertainment System for Transwa’s Fleet of Coaches in Australia Icomera has recently completed the roll-out of an onboard entertainment system for Transwa’s luxury coach fleet, further increasing comfort levels for passengers travelling with Western Australia's regional public transport provider. ENGIE Solutions, through its subsidiary Icomera, is the world's leading provider of wireless Internet connectivity for public transport; Transwa’s onboard entertainment system will help facilitate the choice to travel by coach in the region, a move fully in line with ENGIE Solutions' objective to reinvent living environments for a more virtuous and sustainable world. Installed on Transwa’s 23 Volvo B11R Irizar i6 coaches, the “Bring Your Own Device” (BYOD) solution will enable passengers to access a wide range of media content, from Hollywood movies and TV shows, to magazines, audiobooks and games, directly from their personal phones, tablets and laptops. The onboard entertainment content is hosted locally on board the vehicle by Icomera’s powerful X³ multi- modem mobile access & applications router; the media content on offer will be regularly refreshed over- the-air and fleet-wide using the mobile Internet connection supplied by Icomera’s platform. Tim Woolerson, General Manager at Transwa, said: “As a regional public transport provider in a state as vast as Western Australia, our aim at Transwa is to improve the amenity for passengers on what are often very long trips (on average 300 -

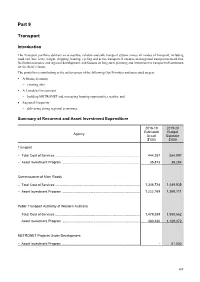

2019-20 Budget Statements Part 9 Transport

Part 9 Transport Introduction The Transport portfolio delivers an accessible, reliable and safe transport system across all modes of transport, including road, rail, bus, ferry, freight, shipping, boating, cycling and active transport. It ensures an integrated transport network that facilitates economic and regional development, and focuses on long-term planning and investment in transport infrastructure for the State’s future. The portfolio is contributing to the achievement of the following Our Priorities and associated targets: • A Strong Economy − creating jobs; • A Liveable Environment − building METRONET and increasing housing opportunities nearby; and • Regional Prosperity − delivering strong regional economies. Summary of Recurrent and Asset Investment Expenditure 2018-19 2019-20 Estimated Budget Agency Actual Estimate $’000 $’000 Transport − Total Cost of Services ........................................................................................... 444,257 554,997 − Asset Investment Program .................................................................................... 35,873 38,284 Commissioner of Main Roads − Total Cost of Services ........................................................................................... 1,346,728 1,489,935 − Asset Investment Program .................................................................................... 1,222,169 1,265,111 Public Transport Authority of Western Australia − Total Cost of Services .......................................................................................... -

Timetable Merredinlink Avonlink

Bookings Wheelchair Passengers Reservations are essential on all services, excluding the Transwa trains and road coaches are fitted to accommodate AvonLink, and may be made up to three months in advance. To people in wheelchairs. Bookings are essential and any book call 1300 662 205 (Australia wide, cost of a local call) from requirements should be explained to ensure availability. Some 8.30am - 5.00pm Monday to Friday, 8.30am - 4.30pm Saturday restrictions apply for motorised gophers/scooters. and 10.00am - 4.00pm Sunday (WST), or visit a Transwa Timetable booking centre or an accredited ticketing agent (locations can Payment be found on our website). Alternatively, visit transwa.wa.gov.au. Ticket payments made via telephone or online are accepted by MerredinLink AvonLink TTY callers may call the National Relay Service on 13 36 77 then Visa and MasterCard. Transwa booking centres, Prospector and quote 1300 662 205. Australind services also accept Visa, MasterCard or EFTPOS East Perth Terminal Midland for payment. Payment for tickets on board any road service, Concessions AvonLink or MerredinLink service is by CASH only. Please check At Transwa we offer discounted travel for all ages, including with accredited ticketing agents for payment options. • Midland WA Pensioners, WA Health Care, Seniors, Veterans, full-time • Toodyay students and children under 16 years of age. If you would like Cancellations • Toodyay to purchase a ticket using your valid concession ensure you Refunds will only be made when tickets are cancelled prior to have your card on you when you book, and while on board. If the scheduled departure of the booked service and are only • Northam required, you may be asked to show another form of ID. -

September 2013

OCM068.3/10/13 THEVOICEOFLOCALGOVERNMENT SEPTEMBER 2013 STATECOUNCILFULL MINUTES WALGA State Council Meeting Wednesday 4 September 2013 Page 1 W A L G A State Council Agenda OCM068.3/10/13 NOTICE OF MEETING Meeting No. 4 of 2013 of the Western Australian Local Government Association State Council to be held at WALGA, 15 Altona St, West Perth on Wednesday 4 September 2013 beginning at 4:00pm. 1. ATTENDANCE, APOLOGIES & ANNOUNCEMENTS 1.1 Attendance Chairman President of WALGA Mayor Troy Pickard Members Avon-Midland Country Zone Cr Lawrie Short Pilbara Country Zone Mayor Kelly Howlett (Deputy) Central Country Zone Mayor Don Ennis Central Metropolitan Zone Cr Janet Davidson JP Mayor Heather Henderson East Metropolitan Zone Mayor Terence Kenyon JP Cr Mick Wainwright Goldfields Esperance Country Zone Mayor Ron Yuryevich AM RFD Great Eastern Country Zone President Cr Eileen O’Connell Great Southern Country Zone President Cr Ken Clements (Deputy) Kimberley Country Zone Cr Chris Mitchell Murchison Country Zone President Cr Simon Broad Gascoyne Country Zone Cr Ross Winzer North Metropolitan Zone Cr Stuart MacKenzie (Deputy) Northern Country Zone President Cr Karen Chappel Peel Country Zone President Cr Wally Barrett South East Metropolitan Zone Mayor Cr Henry Zelones JP Cr Julie Brown South Metropolitan Zone Mayor Cr Carol Adams Cr Doug Thompson Cr Tony Romano South West Country Zone President Cr Wayne Sanford Ex-Officio Local Government Managers Australia Dr Shayne Silcox Secretariat Chief Executive Officer Ms Ricky Burges Deputy Chief Executive -

2004–05 Budget

2004–05 BUDGET BUDGET STATEMENTS Volume 3 PRESENTED TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ON 6 MAY 2004 Budget Paper No.2 2004–05 Budget Statements (Budget Paper No. 2 Volume 3) © Government of Western Australia Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced, with appropriate acknowledgement, as permitted under the Copyright Act. For further information please contact: Department of Treasury and Finance 197 St George’s Terrace Perth WA 6000 Telephone:+61 8 9222 9222 Facsimile: +61 8 9222 9117 Website: http://ourstatebudget.wa.gov.au Published May 2004 John A. Strijk, Government Printer ISSN 1448–2630 BUDGET 2004-05 BUDGET STATEMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume Page Chapter 1: Consolidated Fund Expenditure Estimates ............... 1 1 Chapter 2: Net Appropriation Determinations ............................ 1 23 Chapter 3: Agency Information in Support of the Estimates ...... 1 33 PART 1 – PARLIAMENT Parliament .......................................................................................... 1 37 Parliamentary Commissioner for Administrative Investigations ....... 1 54 PART 2 - PREMIER; MINISTER FOR PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGEMENT; FEDERAL AFFAIRS; SCIENCE; CITIZENSHIP AND MULTICULTURAL INTERESTS Premier and Cabinet........................................................................... 1 67 Royal Commission Into Whether There Has Been Any Corrupt or Criminal Conduct by Western Australian Police Officers ........... 1 106 Anti-Corruption Commission............................................................. 1 110 Governor's Establishment.................................................................. -

Australind Timetable TTY Callers May Call the National Relay Service on 13 36 77 Then Visa and Mastercard

Bookings Wheelchair Passengers Reservations are essential on all services, excluding the Transwa trains and road coaches are fitted to accommodate AvonLink, and may be made up to three months in advance. To people in wheelchairs. Bookings are essential and any book call 1300 662 205 (Australia wide, cost of a local call) from requirements should be explained to ensure availability. Some 8.30am - 5.00pm Monday to Friday, 8.30am - 4.30pm Saturday restrictions apply for motorised gophers/scooters. and 10.00am - 4.00pm Sunday (WST), or visit a Transwa booking centre or an accredited ticketing agent (locations can Payment be found on our website). Alternatively, visit transwa.wa.gov.au. Ticket payments made via telephone or online are accepted by Australind Timetable TTY callers may call the National Relay Service on 13 36 77 then Visa and MasterCard. Transwa booking centres, Prospector and quote 1300 662 205. Australind services also accept Visa, MasterCard or EFTPOS Perth Station for payment. Payment for tickets on board any road service, Concessions AvonLink or MerredinLink service is by CASH only. Please check At Transwa we offer discounted travel for all ages, including with accredited ticketing agents for payment options. • Armadale WA Pensioners, WA Health Care, Seniors, Veterans, full-time students and children under 16 years of age. If you would like Cancellations • Byford to purchase a ticket using your valid concession ensure you Refunds will only be made when tickets are cancelled prior to have your card on you when you book, and while on board. If the scheduled departure of the booked service and are only • Mundijong required, you may be asked to show another form of ID. -

02 Operational Report

18 PTA Annual Report / Operational Report 02 Operational Report Photo: Stephen Endicott, N&I The summary is broken down as follows: A 2016-17 • 2.1 Our services – fleet, patronage, reliability, summary of our capacity and key operational activities. • 2.2 Fares and other revenue – overview of performance revenue and expenditure. • 2.3 PTA in the community – our commitment in providing to providing satisfactory, safe, well- safe, customer- communicated and sustainable operations. • 2.4 Infrastructure delivery – planning, focussed, projects, maintenance, upgrades and asset management. integrated and • 2.5 Our people – overview of our workforce and our strategy for developing, attracting and efficient transport retaining employees. services. A detailed overview of our targets and performance is available in the key performance indicators. PTA Annual Report / Our Services 19 Within the fleet, 677 buses conform to Euro5 and 2.1 Our services Euro6 emission standards (46 per cent of the total), and 492 buses to Euro4 (33.5 per cent). The other 300 buses conform to Euro0 and 2.1.1 Metro (Transperth) Euro3. Transperth is the brand and operating name of Transperth buses covered 280 standard the public transport system in the greater Perth timetabled bus routes (plus 32 non-timetabled metropolitan area. special event routes), 297 school routes and 10 The Transperth system consists of a bus network, CAT (Central Area Transit) routes. On a typical a fully-electrified urban train system and a ferry weekday this involved operating 15,317 standard service. It is managed by our Transperth branch service trips, 298 school service trips and 981 and covers key functions such as system CAT service trips. -

Transwa Tickets Can Be Purchased Online, Via Lancelin • • York Coolgardie • Telephone Or by Visiting a Transwa Booking • Beverley • Kambalda West

Where weLegend go • Cue Meekatharra • Mt Magnet Australind GE1 GS1 N1 SW1 Kalbarri Yalgoo • AvonLink GE2 GS2 N2 SW2 MerredinLink N3 Mullewa GE3 GS3 SW3 Northampton • Prospector GE4 N4 *Low Level Platform N5 Geraldton Railway Line Destination Service Connection and Station Green Type Transperth Station Contractor Service Route Termination • Morawa Dongara • Port Denison • • Mingenew • Three Springs • Wubin Leeman • • Dalwallinu Carnamah • • Moora Coorow • Bookings Jurien Bay • • Wongan Hills Northam Eneabba • • New Norcia Toodyay and enquiries Cervantes • Cataby • • Bindoon • Goomalling Cunderdin Kellerberrin Merredin Kalgoorlie Tickets Gingin • • Boulder Transwa tickets can be purchased online, via Lancelin • • York Coolgardie • telephone or by visiting a Transwa Booking • Beverley • Kambalda West Joondalup • Quairading • Centre. Bookings are essential for all services East Perth Midland excluding the AvonLink. Terminal Armadale Corrigin • Cockburn Central • Perth Concessions Station • Pingelly Mandurah • Kondinin • Transwa offers a 50% concession to Seniors • Hyden Norseman • Serpentine nationally, WA Pensioners, Veterans and Heath Pinjarra • Kulin Care card holders, WA full-time Students and Waroona • Narrogin Williams • Wagin children aged under 16 years. • Dumbleyung Harvey Lake Ravensthorpe Contact us Australind • Katanning Grace • Esperance Brunswick Junction Kojonup • 1300 662 205 Bunbury Terminal • Boyanup Gnowangerup (TIS 13 14 50) • Collie Busselton • Hearing or speech impaired? • Donnybrook Dunsborough • • Balingup Call via -

Directions to Muresk Institute

Directions to Muresk Institute CLACKLINE–SPENCERS BROOK RD S P E N C E R S B R O O K– YO RK R D T: 1300 994 031 E: [email protected] W: dtwd.wa.gov.au/mureskinstitute Postal address: Muresk Institute, Locked Bag 2, Northam, WA 6401 Location address: Muresk Institute, Spencers Brook Road, Northam, WA 6401 From the west (Perth) • From Midland, take the Great Eastern Highway and head east. • At Clackline, turn right on to Spencers Brook Road just after the Clackline bridge. Continue on this road for approximately 19 km. • Go past the Spencers Brook Tavern, over the railway crossing and the Avon River Bridge. • Look for the Muresk Institute signpost and turn right into Muresk Drive. From the south (Albany) • Travel to York township, continue straight through the main street (Avon Terrace). • Avon Terrace will become Spencers Brook-York Road. • At Spencers Brook there is a T junction, turn right, go over the bridge and then turn right into Muresk Institute. From the north (Geraldton) • Take Great Northern Highway to Moora and then the Piawaning turn off (this is clearly signposted when travelling south along Great Northern Highway, 18km south of Walebing). This road is called the Waddington-Wongan Hills Road. • Once at Piawaning, turn right at the T junction and then take another right once over the railway line (you will then be heading south). From there you will pass through Yerecoin, Calingiri, Bolgart, Toodyay and Clackline. • Drive another 19 km (after turning left at the Clackline T junction), passing through Spencers Brook. -

TRANSWA Ephemera PR14931

TRANSWA Ephemera PR14931 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia CALL NO. DESCRIPTION PR14931/1 Prospector train. Australia’s newest regional passenger train. Paper ‘press out’ model. No date. PR14931/2 Want to be here? Transwa can take you there. Folded brochure. Undated. PR14931/3 Transwa Making the connection to Regional Western Australia. Network Map. Include Prospector Safety Information. Brochure. 2005. PR14931/4 A new name. And a whole new standard of service. Leaflet. Undated [2003?]. PR14931/5 Transwa. Bringing WA closer. Information leaflet. Undated. [2017?] PR14931/6 Transwa. Timetable GS3. Perth to Albany via Bunbury and Walpole. Effective 26 November, 2017. PR14931/7 Transwa. Timetable SW1. Perth to Augusta via Bunbury, to Pemberton via Bunbury and Augusta. Effective 15 February, 2013. PR14931/8 Transwa. Timetable N3. Perth to Geraldton via Northam and Mullewa. Effective 11 March, 2015. PR14931/9 Transwa. Timetable N3. Perth to Geraldton via Northam and Mullewa. Effective 9 December, 2016. PR14931/10 Transwa. Timetable GS2. Perth to Albany via Northam and Narrogin, to Gnowangerup, To Katanning. Effective 14 September, 2015. PR14931/11 Transwa. Timetable N1. Perth to Kalbarri via Eneabba, to Geraldton via Eneabba. Effective 9 December, 2016. PR14931/12 Transwa. Timetable N5. Perth to Geraldton via Jurien Bay. Effective 13 December, 2015. PR14931/13 Transwa. Timetable GE2. Perth to Esperance via Kulin or via Hyden. Effective 9 December, 2016. PR14931/14 Transwa. Timetable SW2. Perth to Pemberton via Bunbury and Donnybrook. Effective 27 December, 2015. PR14931/15 Transwa. Timetable GS1. Perth to Albany via Williams and Kojonup. Effective2 December, 2015. -

Nine New Avonlink Trains This Month Michael Sinclair-Jones

Postage Paid TO THE HOUSEHOLDER Toodyay 6566 West Aust Your locally owned PO Box 100, Toodyay, WA 6566, Phone/Fax: (08) 9574 2106 email - [email protected] or September 2014 community newspaper [email protected] Volume 328 www.toodyayherald.com.au Circulation 3600 Nine new AvonLink trains this month Michael Sinclair-Jones TOODYAY will get nine new weekly AvonLink rail services – including a new weekend service – starting from December 1 under new $6.6 million Royalties for Regions funding. The expanded passenger rail service spells victory for local community activists who have fought hard to save the AvonLink from shock closure announced by former Targa West under fire WA Treasurer Troy Buswell last year. Page 3 WA Nationals Leader Terry Redman announced the new funding at Toodyay Railway Station earlier this month after State Cabinet endorsed a detailed rescue plan prepared by the Wheatbelt Development Commission and Transwa. Two extra daily AvonLink passenger return services on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays will aim to meet local residents’ concerns that the current Local residents vote ‘no’ to bauxite mining at Morangup 7am-6.45pm weekday-only return service is too restrictive. A new AvonLink return service will start on weekends, although Transwa has Morangup unites to yet to decide if it will run on Saturdays or Sundays, or on a mix of both – possibly over six-month trial periods for each. Poppies for Toodyay In addition, the AvonLink will provide fight bauxite mine Page 11 10 extra return services per year for special events, such as Toodyay’s annual MORANGUP residents have vowed to stop One speaker compared this with the Shire Moondyne Festival and Avon Descent two planned new open-cut bauxite mines that of Swan, who they said wrote to all affected white water event that draw thousands of will extend 20km across the Avon Valley and ratepayers within a few months of being told visitors to town. -

Pdf Download

26273 AnnualRpt_PTA 23/9/05 12:57 PM Page a 26273 AnnualRpt_PTA 23/9/05 12:57 PM Page b Fulfilling the Government’s Vision The Organisation for Western Australia The Public Transport Authority (PTA) is required to The Public Transport Authority is responsible for the demonstrate in its annual report that it contributes following transport services in Western Australia: to the State Government achieving its vision for • rail, bus and ferry services in the metropolitan Western Australia.The vision is set out in the 2003 area under the brand Transperth; document Better Planning: Better Services which • public transport services in regional centres; establishes strategic outcome goals under the five • road coach and rail passenger services to headings: regional areas under the brand Transwa; and 1. People and Communities • school buses. 2. The Economy In addition to these transport services, it is 3. The Environment responsible for designing and building transport 4. The Regions infrastructure, principally through its entity New 5. Governance MetroRail which is extending the Perth In this report, the PTA has fulfilled this reporting metropolitan rail network, and for protecting the obligation by identifying the strategic outcomes long-term functionality of Western Australia’s freight applicable to itself and the contribution it has made rail corridor and infrastructure. to them in 2004/05 through: The PTA was formed by the Public Transport • Operational reports which show the Authority Act 2003 and began operating on 1 July effectiveness and efficiency of the PTA’s 2003. transport services - see pages 5-30 • A Better Planning: Better Services report - see pages 31-38 Purpose • Audited and unaudited performance indicator reports - see pages 46-62 To increase the use of public transport through the • Audited financial report - see pages 64-89 provision of customer-focused, safe and cost- effective passenger transport services.