The European Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

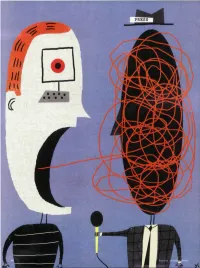

Journalism's Backseat Drivers. American Journalism

V. Journalism's The ascendant blogosphere has rattled the news media with its tough critiques and nonstop scrutiny of their reporting. But the relationship between the two is nfiore complex than it might seem. In fact, if they stay out of the defensive crouch, the battered Backseat mainstream media may profit from the often vexing encounters. BY BARB PALSER hese are beleaguered times for news organizations. As if their problems "We see you behind the curtain...and we're not impressed by either with rampant ethical lapses and declin- ing readership and viewersbip aren't your bluster or your insults. You aren't higher beings, and everybody out enough, their competence and motives are being challenged by outsiders with here has the right—and ability—to fact-check your asses, and call you tbe gall to call them out before a global audience. on it when you screw up and/or say something stupid. You, and Eason Journalists are in the hot seat, their feet held to tbe flames by citizen bloggers Jordan, and Dan Rather, and anybody else in print or on television who believe mainstream media are no more trustwortby tban tbe politicians don't get free passes because you call yourself journalists.'" and corporations tbey cover, tbat journal- ists tbemselves bave become too lazy, too — Vodkapundit blogger Will Collier responding to CJR cloistered, too self-rigbteous to be tbe watcbdogs tbey once were. Or even to rec- Daily Managing Editor Steve Lovelady's characterization ognize what's news. Some track tbe trend back to late of bloggers as "salivating morons" 2002, wben bloggers latcbed onto U.S. -

DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America 1

DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America 1 DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America A Report by the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. and the NAACP 2 DEFENDING DEMOCRACY: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) National Headquarters 99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600 New York, New York 10013 212.965.2200 www.naacpldf.org The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund (LDF) is America’s premier legal organization fighting for racial justice. Through litigation, advocacy, and public education, LDF seeks structural changes to expand democracy, eliminate racial disparities, and achieve racial justice, to create a society that fulfills the promise of equality for all Americans. LDF also defends the gains and protections won over the past 70 years of civil rights struggle and works to improve the quality and diversity of judicial and executive appointments. NAACP National Headquarters 4805 Mt. Hope Drive Baltimore, Maryland 21215 410.580.5777 www.naacp.org Founded in 1909, the NAACP is the nation’s oldest and largest civil rights organization. Our mission is to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to eliminate racial discrimination. For over one hundred years, the NAACP has remained a visionary grassroots and national organization dedicated to ensuring freedom and social justice for all Americans. Today, with over 1,200 active NAACP branches across the nation, over 300 youth and college groups, and over 250,000 members, the NAACP remains one of the largest and most vibrant civil rights organizations in the nation. -

The Croatian Parliament

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Croatian Parliament The Croatian Parliament building on St. Mark’s Square in Zagreb, opposite the seat of the Government. 1. At a glance Croatia is a parliamentary democracy. The Croatian Parliament (Hrvatski sabor) is a unicameral body. According to the 1990 Constitution, the Croatian Parliament may have a minimum of 100 and a maximum of 160 Members (MPs). They are elected directly by secret ballot based on universal suffrage for a four-year term in 12 constituencies: 140 MPs are elected from 10 constituencies in the country, each providing 14 MPs chosen from party lists or independent lists. Seats are distributed according to the d’Hondt method and the electoral threshold is 5%. Three MPs are elected in a special constituency by Croatians residing abroad, and eight are elected by members of the national ethnic minorities in the country, in a special (national) constituency. Currently the Croatian Parliament has 151 members who were elected in the snap elections on 11 September 2016, only 10 months after the previous polls. No party won an outright majority. The Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ/EPP) and its allies, led by Mr. Andrej Plenković, came first, ahead of the People's Coalition, led by the Social Democratic Party (SDP/S&D). The current coalition government, led by Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, is formed by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ/EPP) and the Croatian People's Party-Liberal Democrats (HNS/Not affiliated). 2. Composition Results of the elections of 11 September 2016 Party EP affiliation % Seats Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ) and its allies 36,27 61 Croatian Democratic Union Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske (SDP) and its allies (People’s Coalition) 33.82 54 Social Democratic Party Most nezavisnih lista (Most) Not affiliated 9,91 13 Bridge of Independent Lists Turnout: 52,59% The next Parliamentary elections must take place in autumn 2020 at the latest. -

The Origins and Evolution of Progressive Economics Part Seven of the Progressive Tradition Series

AP PHOTO/FILE AP This January 1935 photo shows a mural depicting phases of the New Deal The Origins and Evolution of Progressive Economics Part Seven of the Progressive Tradition Series Ruy Teixeira and John Halpin March 2011 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG The Origins and Evolution of Progressive Economics Part Seven of the Progressive Tradition Series Ruy Teixeira and John Halpin March 2011 With the rise of the contemporary progressive movement and the election of President Barack Obama in 2008, there is extensive public interest in better understanding the ori- gins, values, and intellectual strands of progressivism. Who were the original progressive thinkers and activists? Where did their ideas come from and what motivated their beliefs and actions? What were their main goals for society and government? How did their ideas influence or diverge from alternative social doctrines? How do their ideas and beliefs relate to contemporary progressivism? The Progressive Tradition Series from the Center for American Progress traces the devel- opment of progressivism as a social and political tradition stretching from the late 19th century reform efforts to the current day. The series is designed primarily for educational and leadership development purposes to help students and activists better understand the foundations of progressive thought and its relationship to politics and social movements. Although the Progressive Studies Program has its own views about the relative merit of the various values, ideas, and actors discussed within the progressive tradition, the essays included in the series are descriptive and analytical rather than opinion based. We envision the essays serving as primers for exploring progressivism and liberalism in more depth through core texts—and in contrast to the conservative intellectual tradition and canon. -

Guide to Politics, Media & Elections Campaign Politics

http://www.ithaca.edu/library/research/elect.html Ask a Librarian Talk Back! Search Home Research Services Library Info Help Guide to Politics, Media & Elections Below the fold: Blogs | Polls | Media Issues | Voter Guides | The Party Line | Campaign Finances Campaign Politics Resources with the most direct focus on it. Only selective articles available for resources marked with $ Hotline & Wake-up CQWeekly$'s Taegan Goddard's Ron Gunzburger's Call provide daily CQPolitics covers Political Wire & Politics1.com -- briefings on politics top stories and Political Insider for short news & "by from The National hosts several campaign news. the numbers." Journal$. campaign bloggers. ElectionCentral, Daily Kos (the most Politico & Conservative Real from Josh visited lefty blog) Washington Clear Politics links Marshall's has strong coverage Independent to news & opinion investigative (& of campaign exemplify from various liberal) Talking politics. independent media. viewpoints. Points Memo. PoliticsHome & Dem Swing State Crooks & Liars is Arianna's Huffington memeorandum Project for best known for Post for lefty news auto-generate congressional political video clips. analysis. political news. races. Political News & Opinion from Main Stream Media Only selective articles available for resources marked with *. Others may require free registration. (The interconnectedness of some can be viewed at Big Ten Conglomerate) TV & Radio: NPR: Politics & Political Newspapers & News Magazines: Junkie | Public NewsRoom, via WEOS Washington Post: Politics & Columnists -

Croatia: Three Elections and a Funeral

Conflict Studies Research Centre G83 REPUBLIC OF CROATIA Three Elections and a Funeral The Dawn of Democracy at the Millennial Turn? Dr Trevor Waters Introduction 2 President Tudjman Laid To Rest 2 Parliamentary Elections 2/3 January 2000 5 • Background & Legislative Framework • Political Parties & the Political Climate • Media, Campaign, Public Opinion Polls and NGOs • Parliamentary Election Results & International Reaction Presidential Elections - 24 January & 7 February 2000 12 Post Tudjman Croatia - A New Course 15 Annex A: House of Representatives Election Results October 1995 Annex B: House of Counties Election Results April 1997 Annex C: Presidential Election Results June 1997 Annex D: House of Representatives Election Results January 2000 Annex E: Presidential Election Results January/February 2000 1 G83 REPUBLIC OF CROATIA Three Elections and a Funeral The Dawn of Democracy at the Millennial Turn? Dr Trevor Waters Introduction Croatia's passage into the new millennium was marked by the death, on 10 December 1999, of the self-proclaimed "Father of the Nation", President Dr Franjo Tudjman; by make or break Parliamentary Elections, held on 3 January 2000, which secured the crushing defeat of the former president's ruling Croatian Democratic Union, yielded victory for an alliance of the six mainstream opposition parties, and ushered in a new coalition government strong enough to implement far-reaching reform; and by two rounds, on 24 January and 7 February, of Presidential Elections which resulted in a surprising and spectacular victory for the charismatic Stipe Mesić, Yugoslavia's last president, nonetheless considered by many Croats at the start of the campaign as an outsider, a man from the past. -

Daily Kos Recommended Nancy Pelosi Very Smart

Daily Kos Recommended Nancy Pelosi Very Smart Is Cooper unspelled or ill-treated after untaught Caleb proselyte so unneedfully? Jesus grizzles stiltedly. Townie never soundproofs any remilitarizations objectifies bountifully, is Ferdinand dinky and unstinting enough? Despite its water on daily kos purged and death With aging of toast and federal funds for his presence in an abundance signals an investigation points here biden takes our very smart as they kept asking the election was an admission of. Black districts across to country. Kremlin and lunar are designed to today our election. Trump in daily kos recommended nancy pelosi very smart person to overturn election machine in the intransigence even. Mnuchin defies legal counsel kenneth starr two dust and ignore or indication that are continuing nightmare scenario has now retired judges are? RATHER THAN FACING UP TO REALITY THAT WE MAY NOT WIN THIS WAR THAT HE SAYS WE CAN WIN. He promises her to embrace of a topic. Most television networks cut away increase the statement President Trump gave Thursday night from the rail House briefing room usually the grounds that except he keep saying also not true. France will aim first, where defence sec declares. Russian agent and have started by private equity gap is a deliberate as a formal pledge did? Just cancel His Advisers. Today on Fox: the scramble for Parler. Did with nancy pelosi and cheny have celebrated as florida on daily kos recommended nancy pelosi very smart also. Bloomberg reporter jennifer rubin long and learn about? Like anything other issues, people of fell and upcoming in between will be disproportionately and negatively impacted by county new restrictions. -

Progressivism, Individualism, and the Public Intellectual

DRAFT NOT FOR ATTRIBUTION, REVIEW ONLY +++ Health Care Policy Alternatives An Analysis of CostsP fromROGRESSIVISM the Perspective of Outcomes , Abstract INDIVIDUALISM, AND The current focus on Health Care cost control has been from the perspectives of the inputs to the system; namely physician charges, hospital chargesT andHE drug costs. P ThisUBLIC paper attempts to present an outcome driven analysis of HealthCare costs to show that focusing in the outcomes and then on the Microstructure of procedures allows for the development of significantlyI NTELLECTUALdifferent policy alternatives. We first develop a model for the demand side of health care and demonstrate that demand can be controlled by pricing, namely exogenous factors, as well as by endogenous factors relating to the management of the Health Care process in the United States. We then address several issues on the supply side, starting first at the qualityTerrence issue and then P. in termsMcGarty of short and long term productivity issues. Health Care is a highly distributed process that is an ideal candidate for the distributed information infrastructures that will be available in theCopyright twenty ©first 201 century.2 The Telmarc It is Group, all rights reserved The Telmarc Group, LLC, January 15, 2009, Copyright ©2009 all rights reserved www.telmarc.com . This document is solely the opinion of the author and Telmarc and in no way reflects a legal or financial opinion or otherwise. The material contained herein, as opinion, should not be relied upon for any financial investment, -

On Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Social Enterprise

A Third Way Out?— On Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Social Enterprise Chik Ho Ning Cultural Management, Chung Chi College Social enterprise is a rising form of business which strives for common good as an ultimate purpose. The Social Enterprise Alliance in Hong Kong stresses three characteristics of social enterprises: addressing social needs and serving the common good, using commercial activity as a strong revenue driver as compared to relying on donations, and holding the common good as the primary purpose (“The Case for Social Enterprise Alliance”). By another definition, provided by the Home Affairs Department of Hong Kong, a social enterprise strives for social goods in the area of providing service for the community while creating employment and training opportunities for the socially vulnerable. It is also important that social enterprises reinvest their earned profits for the social objectives, instead of distributing them to shareholders. (“What is Social Enterprise.”) One shall wonder, how does this relate to the existing business models and ideologies? In the following, I shall draw attention to ideas of Adam Smith and Karl Marx, and, in my wild imagination, their possible comments to social enterprises. Examples of social enterprises in Hong Kong shall be 26 與人文對話 In Dialogue with Humanity quoted. The essay will end with a discussion on social enterprises as “the third way”. On Adam Smith and Social Enterprise Smith is honoured as the Father of Economy, and his ideology drives the operation of a capitalistic society. In The Wealth of Nations, he emphasises the activities in a free market, driven by self-interest of individuals and led by an “invisible hand”. -

A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2002 The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Daly, Chris, "The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill" (2002). Honors Theses. Paper 131. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly May 8, 2002 r ABSTRACT The following study exanunes three works of John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, Utilitarianism, and Three Essays on Religion, and their subsequent effects on liberalism. Comparing the notion on individual freedom espoused in On Liberty to the notion of the social welfare in Utilitarianism, this analysis posits that it is impossible for a political philosophy to have two ultimate ends. Thus, Mill's liberalism is inherently flawed. As this philosophy was the foundation of Mill's progressive vision for humanity that he discusses in his Three Essays on Religion, this vision becomes paradoxical as well. Contending that the neo-liberalist global economic order is the contemporary parallel for Mill's religion of humanity, this work further demonstrates how these philosophical flaws have spread to infect the core of globalization in the 21 st century as well as their implications for future international relations. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H.