Etudes Irlandaises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragging up the Past: Subversive Performance of Gender and Sexual Identities in Traditional and Contemporary Irish Culture

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Dragging up the past: subversive performance of gender and sexual identities in traditional and contemporary Irish culture Author(s) Woods, Jeannine Publication Date 2018 Woods, Jeannine. (2018). Dragging up the Past: Performance Publication of Subversive Gender and Sexual Identities in Traditional and Information Contemporary Irish Culture. In Pilar Villar Argaíz (Ed.), Irishness on the Margins: Minority and Dissident Identities. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Publisher Palgrave Macmillan Link to publisher's https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9783319745664 version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/15189 Downloaded 2021-09-25T10:16:01Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Dragging up the Past: Subversive Performance of Gender and Sexual Identities in Traditional and Contemporary Irish Culture Jeannine Woods This chapter places contemporary drag performance in Ireland within a historical context of dissident, subversive elements of Irish popular culture. The practice of drag, as a performative and political strategy with the potential to disrupt and destabilise fixed gender dichotomies and heteronormative hierarchies of identity, is an international phenomenon associated with the LGBT movement. Drag performance among the LGBT movement in Ireland as explored here serves as a performative practice that queers dominant and intersecting discourses on gender, sexuality and national identity; it also reinflects Bakhtin’s conception of the carnivalesque in a critical engagement with the field of the political. As a practice that draws both on the queer and the carnivalesque, critical drag performance in Ireland both engages with local, national and international cultural politics and also resonates with aspects of traditional Irish popular culture, notably in the context of traditional wake games. -

The Irish Student Movement As an Agent of Social Change: a Case Study Analysis of the Role Students Played in the Liberalisation of Sex and Sexuality in Public Policy

The Irish student movement as an agent of social change: a case study analysis of the role students played in the liberalisation of sex and sexuality in public policy. Steve Conlon BA Thesis Submitted for the Award of Doctorate of Philosophy School of Communication Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr Mark O’Brien May 2016 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctorate of Philosophy is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ______________________ ID No.: 58869651 Date: _____________ i ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to my supervisor Dr Mark O’Brien, a tremendous advocate and mentor whom I have had the privilege of working with. His foresight and patience were tested throughout this project and yet he provided all the necessary guidance and independence to see this work to the end. I must acknowledge too, Prof. Brian MacCraith, president of DCU, for his support towards the research. He recognised that it was both valuable and important, and he forever will have my appreciation. I extend my thanks also to Gary Redmond, former president of USI, for facilitating the donation of the USI archive to my research project and to USI itself for agreeing to the donation. -

11 February Draft

“I’m Coming Out” The expression of queer identity through Irish nightclub flyers, 1980s—2000s Emer Brennan 2018 Visual Communication Design IADT Dun Laoghaire !i This dissertation is submitted by the undersigned to the Institute of Art Design and Technology, Dun Laoghaire in partial fulfilment for the BA (Hons) in Visual Communication. It is entirely the author’s own work, except where noted, and has not been submitted for an award from this or any other educational institution. Signed:____________________________________________________________________ Title image: GAG nightclub flyer, Niall Sweeney, 1996 Courtesy of the Irish Queer Archive Abstract This dissertation examines the expression of queer identity through Irish nightclub posters and flyers from the Irish Queer Archive in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. It gives a cultural and historical context of Ireland and it’s relation to the LGBT community and maps out political and cultural shifs that create social change and set the basis for a more accepting society and community. Further investigation is made into queer culture and how international queer culture affects and influences Ireland at the end of the 20th century. With the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Ireland in June 1993, the boom in club culture and the opening of super clubs in the mid 1990s, a new social scene was created in Dublin for people of all genders, sexualities and interests. The graphic design and production of the flyers and posters for gay nightclubs and events not only created the beginning of a new social scene in Ireland, but also of a new distinct graphic style that is very specific to Dublin and very specific to the time. -

CHROMA. Exhibition Guide. IMMA, Dublin. 2019

IMMA PROJECT SPACES 06 DEC 2019 - 29 MAR 2020 CHROMA Large Print Guide Chroma, A Book of Colour – June ‘93 by Derek Jarman is an intensely personal exploration of colour, written during the final year of the artist’s life as his eyesight failed him. Described as an AIDS autobiography, Chroma is also a work of visceral prose, merging aesthetic and queer thinking with the intensely personal, and politically reactive. Published in the same year as the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the Republic of Ireland, Chroma subverts perceived populist norms and is, by default, an inclusive read. Taking this as its cue, CHROMA explores a prism of protest in various guises of play, art, dance, film, language, politics and poetics. Project themes include bodily relations to colour and space, identity politics, cultural blindness, forced anonymity, and the theatrics of (in)visibilities. Embracing the self-determination and quest for personal freedom that underlines many LGBTQ personal histories and experiences, the project will build new alliances across the queer community, providing a dazzling plinth to co- host a multivocal programme of discussions, screenings, workshops and experimental performances. The project interweaves chromatic musings, evocative memories and archival reflections on continued desires to integrate and transform society. Featured projects include Club Chroma by artist and designer Niall Sweeney of Pony Ltd., who turns the gallery into a glittering stage for celebrating colourful community. This draws on Pony’s Page Two Queer Notions, Alternative Miss Ireland collective studio archive, and longstanding manifesto of subverting conformity through dancing, dressing-up and having fun. Featuring interactive agitprops and projected imagery from twenty five years of the Alternative Miss Ireland scene, Niall calls on visitors to unite in becoming agitators, visionaries and glorious outsiders. -

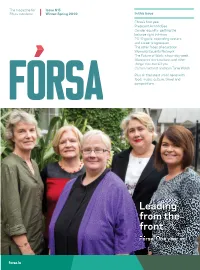

Fo Rsa Issue 5 Cover Layout 1

The magazine for Issue No5 Fórsa members Winter-Spring 2019 In this issue Fórsa’s first year President Ann McGee Gender equality: getting the balance right in Fórsa 2019 goals: expanding sectors and career progression The other faces of education Women’s Equality Network The Future of Work: a four-day week ‘Always on’ work culture, and other things that can kill you Cultural activist and icon Tonie Walsh Plus all the latest union news with food, music, culture, travel and competitions. Leading from the front Fórsa: One year on forsa.ie LOOKING FOR AN ALTERNATIVE TO YOUR EXISTING HOME INSURANCE POLICY? JLT Ireland can offer you a very competitive home For all insurance quote. new policies taken out enjoy Call our team today on €25 1800 200 200 or visit www.jltonline.ie CASH BACK as a gift to you! Subject to underwriting and acceptance criteria. Terms and conditions apply. JLT Insurance Brokers Ireland Limited trading as JLT Ireland, JLT Financial Services, GIS Ireland, Charity Insurance, Teacherwise, Childcare Insurance, JLT Online, JLT Trade Credit Insurance, JLT Sport is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland Directors: Eamonn Bergin, Paul Doherty, Adrian Girling (British), Aidan Gordon, Patrick Howett, Michael Lacey, Dan McCarthy, Raymond O’Higgins. Registered Office: Cherrywood Business Park, Loughlinstown, Dublin 18. A member of Jardine Lloyd Thompson Group plc. Registered in Ireland No. 21622. VAT No. 0042175W. Private Company Limited by Shares. President’s foreword One year on and Winter-Spring 2019 Leading from looking good Fórsa the front Fórsa: One year on AS WE mark the first year of Fórsa in this edition, and look forward to a full and challenging year ahead in 2019, I am keen to express my personal gratitude to all of Fórsa is produced by Fórsa trade the people who’ve worked so hard to make this past year a success. -

Download the Archive Issue 18

TheJournal of The Cork FolkloreArchive Project • Iris Bhéaloideas Chorcaí Issue 18 • 2014 Free Copy Uimhir a hOcht Déag ISSN 1649 2943 Contents The Archive Project Team 3 Vampires in Folklore Project Manager: Mary O’ Driscoll By Dr Jenny Butler Editorial Advisor: Ciarán Ó Gealbháin Design/Layout: Dermot Casey 4 Our Treasure Editorial Team: Alvina Cassidy, Seán Moraghan, By Billy MacCarthy Mary O’Driscoll, Ciarán Ó Gealbháin Research Director: Dr Clíona O’ Carroll 5 Goodbye to Crowley’s Project Researchers: Alvina Cassidy, Stephen Dee, By Dr Marie-Annick Desplanques Geraldine Healy, Penny Johnston, 6 A Life Less Ordinary: The Patrick Hennessy Story Annmarie McIntyre, Seán Moraghan, Margaret Steele, Ian Stephenson By Stephen Dee 8 The Fighting Irish: Faction Fighting in Cork Acknowledgements The Cork Folklore Project would like to thank: Dept By Seán Moraghan of Social Protection, Susan Kirby; Management 10 Getting the Hang of It: Competition and Community in and staff of Northside Community Enterprises; Fr John O’Donovan, Noreen Hegarty, Roinn an Cork’s Ring Leagues Bhéaloidis / Dept of Folklore and Ethnology, By Margaret Steele University College Cork, Dr Stiofán Ó Cadhla, Dr Marie-Annick Desplanques, Dr Clíona O’Carroll, 12 William Thompson: Cork’s Forgotten Pioneer of Social Ciarán Ó Gealbháin, Bláthnaid Ní Bheaglaoí and Science, Women’s Rights and Co-operatives Colin MacHale; Cork City Council, Cllr Kieran McCarthy; Cork City Heritage Officer, Niamh By Dr Ian Stephenson Twomey; Cork City and County Archives, Brian 14 Sound Excerpts McGee; Cork City Library, Local Studies; Blarney Nursing and Retirement Home; Brian O’ Connor, Excerpts from interviews conducted for our DVD Michael Lenihan, Dan Breen, Dr Carol Dundon, If the Walls Could Talk selected by Ian Stephenson, Nuala de Burca. -

ED MADDEN Department of English Home

ED MADDEN curriculum vitae Department of English Home Address: University of South Carolina 1906 Melissa Lane Columbia, SC 29208 Columbia, SC 29210 803.777.4203 803.731.5280 / 803.445.4129 (cell) [email protected] [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Associate Professor of English, University of South Carolina Interim Director, Women’s & Gender Studies Program, USC • Research interests: late 19th-century and 20th-century British and Irish poetry, British and Irish modernisms, Irish culture, sexuality studies • Teaching experience: 19th and 20th-century British literature, Irish literature (including study abroad in Ireland), sexuality studies, literature and AIDS, creative writing, pedagogy EDUCATION • Ph.D., English, University of Texas, Austin, TX, August 1994 Dissertation: “Lyrical Transvestism: Gender and Voice in Modernist Literature” Major field: late 19th- and early 20th-century English poetry Director: Elizabeth Cullingford • B.S., Biblical Studies, summa cum laude, Institute for Christian Studies (now Austin Graduate School of Theology), Austin, TX, 1992 • M.A., English, University of Texas, Austin, TX, 1989 Thesis: “Fetish, Space, Boundary: Theories of Textual Desire and Sharon Olds’s Poetic Practice” • B.A., English and French, summa cum laude, Harding University, Searcy, AR, 1985 PUBLICATIONS Books • Tiresian Poetics: Modernism, Sexuality, Voice 1888-2001. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2008. • Nest [poems]. Cliffs of Moher, Ireland: Salmon Poetry, 2014.. • Prodigal: Variations [poems.] Maple Shade, NJ: Lethe Press, 2011. • Signals: Poems. Winner of the 2007 South Carolina Poetry Book Prize. Forward by Afaa Weaver. Columbia, SC: U of SC Press, 2008. Finalist for the 2009 SIBA Book Award in poetry. Edited collections • Out Loud: The Best of Rainbow Radio [collection of radio essays]. -

DAA Annual Report 2010

A nnual R eport 2 010 Dublin AIDS Alliance Dublin AIDS Alliance Ltd — Annual Report 2010 1—2 Dublin AIDS Alliance (DAA) is a registered charity operating Our Mission at local, national and European level. The principal aim of Working to improve conditions for people living with HIV and AIDS, their the organisation is to improve, through a range of support families and their caregivers, while actively promoting HIV and sexual health services, conditions for people living with HIV and AIDS and/ awareness in the general population. or Hepatitis, their families and their caregivers, while further promoting sexual health in the general population. Since 1987, Our Vision DAA has been pioneering services in sexual health education To contribute to a reduction in the prevalence of HIV in Ireland. and promotion, and has consistently engaged in lobbying and campaigning in the promotion of human rights. Organisational Objectives: – To support those living with and affected by HIV and AIDS – To confront the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV and AIDS – To increase public awareness through the promotion of HIV and sexual health education Background – To influence policy through partnership and active campaigning DAA is acutely aware of the cultural and economic barriers that can affect life choices, rendering both men and women more vulnerable to HIV. Our support, prevention, education and training programmes are therefore rooted in capacity building and experiential learning techniques, which enable the negotiation of safer sex and/or injecting practices. While supporting service users around the choices available, DAA’s approach broadly reflects a harm minimisation model, which emphasises practical rather than idealised goals. -

The Diceman's Queer Performance Activism And

Études irlandaises 42-1 | 2017 Incarner / Désincarner l’Irlande Making a Scene: The Diceman’s Queer Performance Activism and Irish Public Culture Tina O’Toole Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5170 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.5170 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 29 June 2017 Number of pages: 179-185 ISBN: 978-2-7535-5495-5 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Tina O’Toole, « Making a Scene: The Diceman’s Queer Performance Activism and Irish Public Culture », Études irlandaises [Online], 42-1 | 2017, Online since 29 June 2019, connection on 07 September 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5170 ; DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.5170 © Presses universitaires de Rennes Making a Scene: The Diceman’s Queer Performance Activism and Irish Public Culture Tina O’Toole University of Limerick, Ireland Abstract This essay explores two key interventions in the twentieth-century urban history of Irish LGBTQ+ protest. Over the past five decades, there has been a transformation in attitudes to / representations of sexual identities in Ireland. Ever since 1983, when a broad-based protest march moved through Dublin in response to the gaybashing and murder of Declan Flynn in Fairview Park, street demonstrations, guerrilla theatre, and public performance have been used by Irish queer activists to protest the pathologising of sexualities and impact of biopower on all of our lives. Focusing on the street theatre of “The Diceman” [Thom McGinty], this essay captures the public staging of Irish queer resistance in 1980s/90s Dublin. Drawing on Judith Butler’s theory of performance activism (and its roots in Hannah Arendt’s work), it explores the The Diceman’s key role in creating a public identity for Irish LBGTQ+ people in the period before the decriminalization of (male) homosexuality in 1993. -

Gay Visibility in the Irish Media, 1974-2008

Queering in the Years: Gay Visibility in the Irish Media, 1974-2008 Páraic Kerrigan A major thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Studies Maynooth University Department of Media Studies October 2018 Supervisors: Professor Maria Pramaggiore and Dr. Stephanie Rains Head of Department: Dr. Kylie Jarrett Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………...….v Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….....……..vi List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………..………....ix List of Appendices………………………………………………………………..…………xi List of Abbreviations and Acronyms…………………………………………………………………………...xii Introduction: Did They Really Notice Us?...............................................................1 Queer Media and Irish Studies…………………………………………………….5 Que(e)rying Irish Media Visibility……..………………………………………...12 Methodological Approach……………………………..…………………………14 Structural Approach………………………..…………………………………….18 Chapter One: ‘Lavender Flying Columns’ and ‘Guerrilla Activism’: The Politics of Gay Visibility Introduction……………………………………………………..………………..22 Visibility as Social Recognition……………………..…………………………...23 Theorising Queer Visibility………………………..……………………………..25 Visibility and Irish Media History…………………………………...…………...31 Discourses of Queer Irish Visibility…………………………………..………….35 Transnational Queer Visibility…………………………………………..……….43 Conclusion…………..……………………………………………………………45 Chapter Two: Respectably Gay?: Queer Visibility on Broadcast Television (1975-1980) Introduction…………………….…………………………………………………..46 Mainstreaming and the Confessional………………………………..…………...48 -

Études Irlandaises, 42-1 | 2017, « Incarner / Désincarner L’Irlande » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 29 Juin 2019, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020

Études irlandaises 42-1 | 2017 Incarner / Désincarner l’Irlande Embodying / Disembodying Ireland Fiona McCann et Alexandra Poulain (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5077 DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.5077 ISSN : 2259-8863 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Caen Édition imprimée Date de publication : 29 juin 2017 ISBN : 978-2-7535-5495-5 ISSN : 0183-973X Référence électronique Fiona McCann et Alexandra Poulain (dir.), Études irlandaises, 42-1 | 2017, « Incarner / Désincarner l’Irlande » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 29 juin 2019, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/5077 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesirlandaises. 5077 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2020. Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Erratum Comité de rédaction Introduction Fiona McCann et Alexandra Poulain Corps de femmes, corps dociles : le cas Magdalen Laundries Nathalie Sebbane De-composing the Gothic Body in Maria Edgeworth’s Castle Rackrent Nancy Marck Cantwell “Away, come away”: Moving Dead Women and Irish Emigration in W. B. Yeats’s Early Poetry Hannah Simpson An Uncanny Myth of Ireland: The Spectralisation of Cuchulain’s Body in W. B. Yeats’s Plays Zsuzsanna Balázs Embodying the Trauma of the Somme as an Ulster Protestant Veteran in Christina Reid’s My Name, Shall I Tell You My Name? Andréa Caloiaro Intimations of Mortality: Stewart Parker’s Hopdance Marilynn Richtarik Performing trauma in post-conflict Northern Ireland: ethics, representation and the witnessing body Alexander Coupe Ciaran Carson and the Theory of Relativity Julia C. -

Billy Quinn: an Artist for a Time of Plague Work from the 1990S

Billy Quinn: An Artist for a Time of Plague Work from the 1990s Patrick Anthony Caffrey MPhil in Irish Art History 2017 University of Dublin, Trinity College Dublin 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Patrick Anthony Caffrey 2 Acknowledgements This has been nothing if not a collaborative effort. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Catherine Lawless, for her encouragement and guidance. Second, my thanks to the staff of the Department of History of Art and Architecture, in particular Laura Cleaver and Yvonne Scott of TRIARC. My thanks also are owed to Catherine Marshall, who was instrumental in introducing me to Billy Quinn, without whose generosity and patience this effort could not have come to fruition. Thanks also to my friend Martin McCann who introduced me to John McBratney, Alan Phelan, Tonie Walsh, Mick Wilson and Aengus Carroll. For assistance in gaining access to the IMMA archive, my thanks to Seán Kissane and Olive Barre, both of IMMA. Thanks also to Seán Hughes, Subject Librarian at TCD, for his advice and patience with my grappling with Endnote. There are others to whom I am indebted, in particular my cousin Margaret who patiently read and commented on everything I wrote.