The French Connection Programme Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU

RAMEAU LES BORÉADES Václav Luks MENU Tracklist Distribution L'œuvre Compositeur Artistes Synopsis Textes chantés L'Opéra Royal 1 MENU LES BORÉADES VOLUME 1 69'21 1 Ouverture 2'28 2 Menuet 0'44 3 Allegro 1'32 ACTE I 4 Scène 1 - Alphise et Sémire 3'19 Récits en duo et Airs d'Alphise «Suivez la chasse» Deborah Cachet, Caroline Weynants 5 Scène 2 - Borilée et les Précédents 0'29 Air et Récit de Borilée «La chasse à mes regards» Tomáš Šelc 6 Scène 3 - Calisis et les Précédents 2'08 Récit et Air de Calisis «À descendre en ces lieux» Deborah Cachet, Benedikt Kristjánsson 7 Scène 4 - Troupe travestie en Plaisirs et Grâces 0'35 Air de Calisis «Cette troupe aimable» Caroline Weynants, Benedikt Kristjánsson 8 Air gracieux (Ballet) 1'51 9 Air de Sémire «Si l'hymen a des chaines» – Caroline Weynants 0'40 10 Première Gavotte gracieuse 0'32 11 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'46 12 Première Gavotte da capo (Ballet) 0'18 2 13 Air de Calisis «C'est dans cet aimable séjour» – Benedikt Kristjánsson 0'46 14 Rondeau vif (Ballet) – Caroline Weynants 2'23 15 Gavotte vive (Ballet) 0'51 16 Deuxième Gavotte (Ballet) 0'53 17 Ariette pour Alphise ou la Confidente (Sémire) «Un horizon serein» 7'37 Deborah Cachet ou Caroline Weynants 18 Contredanse en Rondeau (Ballet) 1'57 19 L'Ouverture pour Entracte ACTE II 20 Scène 1 - Abaris 2'25 Air d'Abaris «Charmes trop dangereux» Mathias Vidal 21 Scène 2 - Adamas et Abaris 0'31 Récit d'Adamas «J'aperçois ce mortel» Benoît Arnould 22 Air d'Adamas «Lorsque la lumière féconde» – Benoît Arnould 1'08 23 Récit d'Abaris et Adamas «Quelle -

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Tbsi Orch-Choir Repertoire 02-17

ORCHESTRA & CHOIR REPERTOIRE FROM PAST INSTITUTES TBSI 2017 Fasch/Purcell Orchestra [dir. J. Lamon] Fasch Concerto in D Minor (2 fl, 2 ob, 2 bsn, str 4/5/3/3/1, 2 hp) Purcell Suite from Ayres for the Theatre (str 4/5/3/3/1, 2 hp, 3 lute/gtr) Lully/Vivaldi Orchestra [dir. J. Lamon] Lully Suite from Phaëton (4 fl, 3 obs, 4 bsn, 6 vln, 4 haute-contre, 3 taille, 2 quinte, 4 vc, 2 cb, 2 hp, 2 lute/gtr) Vivaldi Concerto for strings in C Major, RV 117 (str 5/5/5/4/2, 2 hp, 2 lute) Cantata Choir [dir. I. Taurins] J. Ch. Bach Sterb-Aria “Es is nun aus” (SS-AA-ATT-BB) J.S. Bach Chorus “Christum wir wollen loben” from Cantata 121 (SS-AA-TT-BB + 2 vln, vla, bsn, vc, cb, org) Chorus “Brich den Hungrigen dein Brot” from Cantata 39 (SS-AA-TT-BB + 2 ob, 4 vln, vla, bsn, vc, cb, org) Kyrie Choir [dir. I. Taurins] Purcell Anthem “I was glad” (SS-SS-AA-TT-BB + org) J.S. Bach Kyrie-Christe du Lamm Gottes, BWV 233a (SS-SS-AA-TT-BB + vc, cb, org) Cum sancto spiritu, from Mass in A Major, BWV 234 (SSS-AAA-TT-BB + fl, 2 vln, vla, vc cb, org) Grand Finale 2017 Handel Concerto grosso op. 6, no. 9 [dir. J. Lamon] (str 12/11/9/8/6, 4 hp, org, 4 lute) Rameau Suite from Zoroastre & Les Fêtes d’Hébé [dir. J. Lamon] (7 fl, 5 ob, 7 bsn, str 12/11/5 h-c/4 taille/8/6, 8 lute/gtr, 4 hp) Charpentier Messe des Morts, H.10 [dir. -

Jean-Philippe Rameau 讓-菲利普·拉摩

18th Century French Keyboard Music & Ornamentation 生平 • 1683年-1764年 • 生涯分早期(1683-1732)與後期(1733-1764) • 法國人 生平-早期(1) • 早期為1683年-1732年。 • 生於法國第戎(Dijon)。 • 父親在教堂擔任管風琴手;母親(Claudine Demartinécourt)來 自貴族家庭。 • 家中共有11個小孩,5個女生和6個男生,拉摩排名第7。 • 拉摩幼年時被送往戈德朗斯(Godrans)的耶穌會學院學習法律, 但他真正喜愛的是音樂和作曲,在決定未來要成為一位音樂 家後,他父親便讓他前往義大利米蘭學習音樂。 生平-早期(2) • 1706年,在米蘭的拉摩出版了他知名的作品《大鍵琴曲集》 (Pièces de clavecin)第一部。 • 1709年,他回到第戎並接手他父親在巴黎聖母院管風琴手 的職位,還創作了不少供教堂表演的經文歌和世俗清唱劇。 • 1722年,他前往巴黎,出版了他此 生最重要的理論作品《和聲學》 (Traité de l‘harmonie),因而聲名大噪。 生平-早期(3) • 1726年,拉摩又發表了另外一本理論作品《音樂理論的新 體系》(Nouveau système de musique théorique)。 • 1726年二月,他娶了19歲的 瑪麗-路易絲·芒戈(Marie- Louise Mangot)為妻,她是一 位出色的歌手及器樂家,他 們共生了4個小孩,2男2女。 生平-後期(1) • 後期為1733年-1764年。 • 直到拉摩50歲,才開始了他的歌劇創作生涯。 • 1732年,受到Montéclair的歌劇作品“Jephté”影響,他開始 著手他的法國歌劇創作─抒情悲劇(tragédie en musique)。 • 1733年,他的第一部歌劇《希波呂托斯與阿里奇埃》 (Hippolyte et Aricie)於10月1日公演而造成轟動,被眾人認 為是繼盧利之後,最偉大的歌劇作品。 生平-後期(2) • 《希波呂托斯與阿里奇埃》問世後,觀眾反應兩極,有 一派認為這部作品不僅有拉摩自己的原創性,還做了許 多創新;另一派則指出這部作品在和聲上的創新是不和 諧的,認為拉摩牴觸了法國的傳統音樂。 • 此後,兩派便發展成所謂的「盧利派」(Lullyistes),以及 「拉摩派」(Rameauneurs),也因為這個事件爭吵了至少 十年之久。 生平-後期(3) • 這段時期,他還認識了一個很有勢力的財主Alexandre Le Riche de La Pouplinière(後來在1753年時成為拉摩的贊助者)。 • 1731年,拉摩擔任La Pouplinière的私人樂團指揮,長達22 年之久,也藉此認識了很多當時文化的領導人物。 • 後來拉摩也將他新式的音樂風格移植到歌劇芭蕾(opéra- ballet)去創作,像是作品《殷勤的印第安人》(Les Indes galantes)獲得很高的評價。 生平-後期(4) • 1737年與1739年,創作抒情悲劇《雙子星卡斯托耳與波呂 丟刻斯》(Castor et Pollux)以及《達耳達諾斯》(Dardanus) 。 • 同年,還創作另一部歌劇芭蕾─《赫伯的節日或抒情天才》 (Les fêtes d‘Hébé)。這些都被視為拉摩最出色的歌劇作品。 • 1741年,他創作了此生唯一的室內樂作品《大鍵琴合奏曲 集》(Les pièces de clavecin en concert)。 生平-後期(5) • 1745年他被任命為王家室內樂作曲家(Compositeur de -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02156-3 - Dramatic Expression in Rameau’s Tragédie en Musique: Between Tradition and Enlightenment Cynthia Verba Index More information Index accompanied recitative chromatics, 27, 38, 62, 68, 69, 72, 75–76, 78, as tonal anchors, 32 80, 86, 88–89, 92–93, 140, 147, 148, in Dardanus, 131, 194–196, 203 169, 175, 176, 179, 185, 186, 193, 196, in Hippolyte et Aricie, 66, 67, 72, 79–80, 90, 210, 244, 249, 286, 291 115 classical models of tragedy, 85, 181 (see also in Les Bor´eades, 218 Aristotelian poetics) in Zoroastre, 292–295 Cohen, David E., 30–31 airs contrary duos, 67–68, 69–71, as tonal anchors, 32, 34, 36 251–253 in Castor et Pollux, 124 Cowart, Georgia, 8–10 in Dardanus, 129, 196–199, 291–292 in Hippolyte et Aricie, 51–53, 54–62, 65, 74, da capo arias, 4, 144, 163, 183–188, 200–203, 79, 80–84, 86, 90–93 210, 212, 247–249 in Les Bor´eades, 169, 171–172, 175, 178–179, terminology, x 214–216, 217–218 D’Alembert,JeanleRond,2–3 in Lully’s operas, 7, 17–18 deities in Zoroastre, 134, 137, 140–141, 147, interventions, imposed by deities, 84, 148–149, 152, 153–154, 155, 203–207 89–90, 116, 117, 118, 119, 123–124, terminology, x, 56 127, 129, 145, 161, 170, 175, 177, 179, Allanbrook, Wye Jamison, 32 301–302 ancien r´egime, 1, 7, 9–11, 14, 16, 108, 109, 314, invocations, addressing deities, 79–84, 316–317 85–89, 112, 115, 116, 125, 146–147, Anthony, James, 16, 20, 21 152–153, 174, 200–203 ariettes, 117, 124, 144, 163–167, 170, 172, 176, Diderot, Denis, 2, 3, 20, 31–32 302 Dill, Charles, 5, 8, 19, 21–22, 44, -

Rameau, Jean-Philippe

Rameau, Jean-Philippe (b Dijon, bap. 25 Sept 1683; d Paris, 12 Sept 1764). French composer and theorist. He was one of the greatest figures in French musical history, a theorist of European stature and France's leading 18th-century composer. He made important contributions to the cantata, the motet and, more especially, keyboard music, and many of his dramatic compositions stand alongside those of Lully and Gluck as the pinnacles of pre-Revolutionary French opera. 1. Life. 2. Cantatas and motets. 3. Keyboard music. 4. Dramatic music. 5. Theoretical writings. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GRAHAM SADLER (1–4, work-list, bibliography) THOMAS CHRISTENSEN (5, bibliog- raphy) 1. Life. (i) Early life. (ii) 1722–32. (iii) 1733–44. (iv) 1745–51. (v) 1752–64. (i) Early life. His father Jean, a local organist, was apparently the first professional musician in a family that was to include several notable keyboard players: Jean-Philippe himself, his younger brother Claude and sister Catherine, Claude's son Jean-François (the eccentric ‘neveu de Rameau’ of Diderot's novel) and Jean-François's half-brother Lazare. Jean Rameau, the founder of this dynasty, held various organ appointments in Dijon, several of them concurrently; these included the collegiate church of St Etienne (1662–89), the abbey of StSt Bénigne (1662–82), Notre Dame (1690–1709) and St Michel (1704–14). Jean-Philippe's mother, Claudine Demartinécourt, was a notary's daughter from the nearby village of Gémeaux. Al- though she was a member of the lesser nobility, her family, like that of her husband, included many in humble occupations. -

Haydn Rawstron Limited

HAYDN RAWSTRON LIMITED Berg - Wozzeck - Madman Berg - Lulu - The Prince Berg - Wozzeck - Captain Berg - Wozzeck - Andres Britten - A Midsummer Night's Dream - Flute Alexander Kravets Tenor Britten - Peter Grimes - Rev. Horace Adams Britten - Peter Grimes - Bob Boles Opera Repertoire Campra - Idomenee - Idamante Page 1/4 Chabrier - Une education manquee - Gontran Charpentier - Medee - Jason Charpentier - Orphee - Orphee Charpentier - David et Jonathas - David Charpentier - Acteon - Acteon Donizetti - La fille du regiment - Tonio Donizetti - Lucia di Lammermoor - Normanno Gluck - Orfeo ed Euridice - Orfeo Gluck - Alceste - Admeto Humperdinck - Hänsel und Gretel - The Gingerbread Witch Janacek - From the House of the Dead - Sapkin Janacek - The Makropolus Case - Hauk-Sendorf Janacek - The Makropolus Case - Vitek Janacek - The Cunning Little Vixen - Schoolmaster Janacek - The Excursions of Mr. Broucek - Matej Broucek September 2015 55 LANGLEY WAY, WEST WICKHAM, KENT BR4 0DH, ENGLAND Telephone: + 44(0)20 8777 9214 Mobile: +44 (0)7889 469941 Email: [email protected] Website: www.haydnrawstron.com Alexander Kravets Janacek - Katia Kabanova - Vana Kudrjash Tenor Opera Repertoire Janacek - Jenufa - Laca Klemen Page 2/4 Leoncavallo - Pagliacci - Beppe Lortzing - Zar und Zimmermann - Marquis de Chateauneuf Lully - Armide - Renaud Lully - Phaeton - Phaeton Lully - Acis et Galathee - Acis Lully - Alceste - Admete Monteverdi - Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria - Telemaco Monteverdi - L'incoronazione di Poppea - Arnalta Monteverdi - L'Orfeo - -

AU's LE BERGER Fideole: an ANALYSIS for PERFORMANCE

RAKV1;AU'S LE BERGER FIDEoLE: AN ANALYSIS FOR PERFORMANCE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Lillian Lucille Loe Denton, Texas December, 1972 Loe, Lillian Lucille, Rameau's Le Berger Fidele: An Analysis for Performance, Master of Music (Voice), December, 1972, 102 pp., 4 tables, 15 illustrations, bibliography, 47 titles. It is assumed that the performer of Le Berger Fidele will be capable of a more accurate performance and a more historically authoritative interpretation if he thoroughly understands all musical aspects of the cantata. Due to the lack of written directions from earlier composers, it is important that the performer research the period, composer, and composition to insure a more accurate, interpretive per- formance. The first chapter delves into the life and works of Rameau. The second chapter follows the development of the French solo cantata from the beginning of the art song to its culmination. Ornaments peculiar to French cantata are dis- cussed in the third chapter. In Chapter IV each pair of recitative and aria is examined and analyzed according to form, harmony, rhythm, melody (including phrasing), dynamics and ornaments, and instrumentation. The cantata is built up in a succession of three arias. Each aria is da capo in form and is preceded by a recitative and an instrumental introduction. Each air is concluded with an instrumental postlude. The instruments (first and second violins, cello, and harpsichord) play an integral part throughout the cantata. The interludes establish or change moods. -

Jean-Philippe Rameau Suite from Naïs

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Jean-Philippe Rameau Born before September 25, 1683, Dijon, France. Died September 12, 1764, Paris, France. Suite from Naïs Rameau composed his dramatic work, Naïs, a pastorale-héroïque, in 1748-49. The premiere was given on April 22, 1749, at the Paris Opera. The orchestra for this suite of instrumental selections consists of four flutes and two piccolos, four oboes, musette (a small French bagpipe), four bassoons, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these performances, the musette is played by Jean-Pierre van Hees. Performance time is approximately thirty minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra first performed Rameau’s Suite from Naïs on April 6, 2006. Jean-Philippe Rameau is one of the orchestral world’s neglected masters. Although he is regularly acknowledged as one of the most important and influential composers of the French baroque, modern symphony orchestras today rarely play his music. When the Chicago Symphony performed Rameau’s music for the first time in 1900, the program book painted him as a worthy companion to Bach, pointing out that when he died “all France mourned for him; Paris gave him a magnificent funeral, and in many other towns funeral services were held in his honor.” The Orchestra played selections from his opera Castor et Pollux the next season, but Rameau’s music was rarely performed again after that. In the past four decades, his name has appeared on Chicago Symphony programs just once, on a pension fund concert in 1981, when the Overture to Les Paladins was performed. A contemporary of Bach and Handel (he was born just two years before them and outlived Bach by fourteen years), Rameau was the greatest French composer of the eighteenth century and one of the giants of the Enlightenment. -

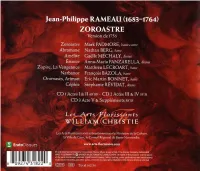

ZOROASTRE Version De 1756

Jean-Philippe RAMEAU (1683-1764) ZOROASTRE Version de 1756 Zoroastre Mark PADMORE, haute<outre Abramane Nathan BERG, basse Amélite Gaëlle MÉCHALY, dessus Érinice Anna-Maria PANZARELLA, dessus Zopire, La Vengeance Matthieu LÉCROART, basse Narbanor François BAZOLA, basse Oromasès, Ariman Éric Martin BONNET, basse Céphie Stéphanie REVIDAT, dessus CD 1 Actes I & 11 68'08 CD 2 Actes 111 & IV 55'51 CD 3 Acte V & Suppléments 38'35 Rameau zoroastre RAMEAU Z O ROAS TRE JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683-1764) Zoroastre^ Livret de Louis de Cahusac Version de 1756 ZOROASTRE, instituteur des Mages Mark Padmore, haute-contre founder of the Magi der Lehrmeister der Magier ABRAMANE, Grand Prêtre d'Ariman Nathan Berg, basse High Priest of Ariman • Oberpriester des Ariman AMÉLITE, héritière présomptive du trône de la Bactriane Gaëlle Méchaly, dessus presumptive heiress to the throne of Bactria die mutmaßliche Thronfolgerin des Königreichs Baktrien ÉRINICE, princesse du sang des rois de la Bactriane Anna Maria Panzarella, dessus princess of the blood ofthe kings ofBactria eine Prinzessin aus dem Geblüt der Könige von Baktrien ZOPIRE, prêtre d'Ariman Matthieu Lécroart, basse priest of Ariman - Priester des Ariman NARBANOR, prêtre d'Ariman François Bazola, basse priest of Ariman Priester des Ariman OROMASÈS, roi des Génies Éric Martin Bonnet, basse king of the Genii - der König der guten Geister CÉPHIE, jeune Bactrienne de la Cour d'Amélite Stéphanie Révidat, dessus Bactrian girl ofAme'lite's court eine junge Baktrerin am Hofe Amelites LA VENGEANCE Matthieu Lécroart, -

Download Booklet

LIGHT DIVINE INTRODUCTION 1 Concerto in F, HWV 331 George Frideric Handel, [4.18] Aksel and I first met in the Oslo Chamber Music Arr. Mark Bennett Festival in 2016. Aksel had already recorded his 2 Eternal Source of Light Divine, HWV 74 George Frideric Handel [3.10] first album in the UK with the Orchestra of the Age 3 Passacaille from Sonata in G, Op. 5, No. 5, HWV 399 George Frideric Handel [4.54] of Enlightenment and had performed some of the Arr. Mark Bennett more well known music for soprano and trumpet. 4 What Passion Cannot Music Raise And Quell, HWV 76 George Frideric Handel [8.18] 5 Alla caccia (Diana cacciatrice), HWV 79 George Frideric Handel [6.25] We worked together on a few more projects and Arr. Mark Bennett continued to play these same pieces. A few months were - in Jar Kirke, Oslo, making it all happen. 6 Vien con nuova orribil guerra, from La Statira Tomaso Albinoni [5.33] later I was given some opportunities to direct and Despite the issues of summer holidays and Ornaments by Mark Bennett lead my own productions and I invited Aksel along. various summer festivals, it just all fell into 7 Ciaccona à 7 Philipp Jakob Rittler [4.58] place. It was a miracle. 8 Ritournelle, from Hippolyte et Aricie Jean-Philippe Rameau [1.50] I started to introduce new repertoire to Aksel Arr. Aareskjold/Bennett and he just seemed to thrive on this challenge. The MIN Ensemble, although a modern 9 Entrée d’Abaris, from Les Boréades Jean-Philippe Rameau [3.47] Projects with The Norwegian Radio Orchestra instrument group, were enthusiastic about my 0 Tristes apprêts, from Castor et Pollux Jean-Philippe Rameau [6.20] and the Oslo-based period instrument orchestra more early music approach.