Power Line Strips Provide Nest Sites and Floral Resources for Cavity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elytra Reduction May Affect the Evolution of Beetle Hind Wings

Zoomorphology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-017-0388-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Elytra reduction may affect the evolution of beetle hind wings Jakub Goczał1 · Robert Rossa1 · Adam Tofilski2 Received: 21 July 2017 / Revised: 31 October 2017 / Accepted: 14 November 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Beetles are one of the largest and most diverse groups of animals in the world. Conversion of forewings into hardened shields is perceived as a key adaptation that has greatly supported the evolutionary success of this taxa. Beetle elytra play an essential role: they minimize the influence of unfavorable external factors and protect insects against predators. Therefore, it is particularly interesting why some beetles have reduced their shields. This rare phenomenon is called brachelytry and its evolution and implications remain largely unexplored. In this paper, we focused on rare group of brachelytrous beetles with exposed hind wings. We have investigated whether the elytra loss in different beetle taxa is accompanied with the hind wing shape modification, and whether these changes are similar among unrelated beetle taxa. We found that hind wings shape differ markedly between related brachelytrous and macroelytrous beetles. Moreover, we revealed that modifications of hind wings have followed similar patterns and resulted in homoplasy in this trait among some unrelated groups of wing-exposed brachelytrous beetles. Our results suggest that elytra reduction may affect the evolution of beetle hind wings. Keywords Beetle · Elytra · Evolution · Wings · Homoplasy · Brachelytry Introduction same mechanism determines wing modification in all other insects, including beetles. However, recent studies have The Coleoptera order encompasses almost the quarter of all provided evidence that formation of elytra in beetles is less currently known animal species (Grimaldi and Engel 2005; affected by Hox gene than previously expected (Tomoyasu Hunt et al. -

Final Report 1

Sand pit for Biodiversity at Cep II quarry Researcher: Klára Řehounková Research group: Petr Bogusch, David Boukal, Milan Boukal, Lukáš Čížek, František Grycz, Petr Hesoun, Kamila Lencová, Anna Lepšová, Jan Máca, Pavel Marhoul, Klára Řehounková, Jiří Řehounek, Lenka Schmidtmayerová, Robert Tropek Březen – září 2012 Abstract We compared the effect of restoration status (technical reclamation, spontaneous succession, disturbed succession) on the communities of vascular plants and assemblages of arthropods in CEP II sand pit (T řebo ňsko region, SW part of the Czech Republic) to evaluate their biodiversity and conservation potential. We also studied the experimental restoration of psammophytic grasslands to compare the impact of two near-natural restoration methods (spontaneous and assisted succession) to establishment of target species. The sand pit comprises stages of 2 to 30 years since site abandonment with moisture gradient from wet to dry habitats. In all studied groups, i.e. vascular pants and arthropods, open spontaneously revegetated sites continuously disturbed by intensive recreation activities hosted the largest proportion of target and endangered species which occurred less in the more closed spontaneously revegetated sites and which were nearly absent in technically reclaimed sites. Out results provide clear evidence that the mosaics of spontaneously established forests habitats and open sand habitats are the most valuable stands from the conservation point of view. It has been documented that no expensive technical reclamations are needed to restore post-mining sites which can serve as secondary habitats for many endangered and declining species. The experimental restoration of rare and endangered plant communities seems to be efficient and promising method for a future large-scale restoration projects in abandoned sand pits. -

LONGHORN BEETLE CHECKLIST - Beds, Cambs and Northants

LONGHORN BEETLE CHECKLIST - Beds, Cambs and Northants BCN status Conservation Designation/ current status Length mm In key? Species English name UK status Habitats Acanthocinus aedilis Timberman Beetle o Nb 12-20 conifers, esp pine n Agapanthia cardui vr herbaceous plants (very recent arrival in UK) n Agapanthia villosoviridescens Golden-bloomed Grey LHB o f 10-22 mainly thistles & hogweed y Alosterna tabacicolor Tobacco-coloured LHB a f 6-8 misc deciduous, esp. oak, hazel y Anaglyptus mysticus Rufous-shouldered LHB o f Nb 6-14 misc trees and shrubs y Anastrangalia (Anoplodera) sanguinolenta r RDB3 9-12 Scots pine stumps n Anoplodera sexguttata Six-spotted LHB r vr RDB3 12-15 old oak and beech? n Anoplophora glabripennis Asian LHB vr introd 20-40 Potential invasive species n Arhopalus ferus (tristis) r r introd 13-25 pines n Arhopalus rusticus Dusky LHB o o introd 10-30 conifers y Aromia moschata Musk Beetle o f Nb 13-34 willows y Asemum striatum Pine-stump Borer o r introd 8-23 dead, fairly fresh pine stumps y Callidium violaceum Violet LHB r r introd 8-16 misc trees n Cerambyx cerdo ext ext introd 23-53 oak n Cerambyx scopolii ext introd 8-20 misc deciduous n Clytus arietus Wasp Beetle a a 6-15 misc., esp dead branches, posts y Dinoptera collaris r RDB1 7-9 rotten wood with other longhorns n Glaphyra (Molorchus) umbellatarum Pear Shortwing Beetle r o Na 5-8 misc trees & shrubs, esp rose stems y Gracilia minuta o r RDB2 2.5-7 woodland & scrub n Grammoptera abdominalis Black Grammoptera r r Na 6-9 broadleaf, mainly oak y Grammoptera ruficornis -

Integrating Cultural Tactics Into the Management of Bark Beetle and Reforestation Pests1

DA United States US Department of Proceedings --z:;;-;;; Agriculture Forest Service Integrating Cultural Tactics into Northeastern Forest Experiment Station the Management of Bark Beetle General Technical Report NE-236 and Reforestation Pests Edited by: Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team J.C. Gregoire A.M. Liebhold F.M. Stephen K.R. Day S.M.Salom Vallombrosa, Italy September 1-3, 1996 Most of the papers in this publication were submitted electronically and were edited to achieve a uniform format and type face. Each contributor is responsible for the accuracy and content of his or her own paper. Statements of the contributors from outside the U.S. Department of Agriculture may not necessarily reflect the policy of the Department. Some participants did not submit papers so they have not been included. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. Remarks about pesticides appear in some technical papers contained in these proceedings. Publication of these statements does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of them by the conference sponsors, nor does it imply that uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by State and Federal Law. Applicable regulations must be obtained from the appropriate regulatory agencies. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish and other wildlife - if they are not handled and applied properly. -

Clear-Cut and Substrate Characteristics Important for the Occurrence of the Beetle Upis Ceramboides

Department of Ecology Clear-cut and substrate characteristics important for the occurrence of the beetle Upis ceramboides Ronny Naalisvaara Master’s thesis Uppsala 2013 Independent project/Degree project / SLU, Department of Ecology 2013:3 Clear-cut and substrate characteristics important for the occurrence of the beetle Upis ceramboides Ronny Naalisvaara Supervisor: Thomas Ranius, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Ecology Examiner: Erik Öckinger, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Ecology Credits: 30 hec Level: A1E Course title: Degree project in Biology/Examensarbete i biologi Course code: EX0009 Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2013 Cover picture: Ronny Naalisvaara Title of series: Independent project/Degree project / SLU, Department of Ecology Part no: 2013:3 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Keywords: Upis ceramboides, dead wood, clear-cut, prescribed burning Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Ecology 1 Abstract Disturbances, such as fire and wind, are important for saproxylic beetles (= beetles depending on decaying wood) to gain substrate in boreal forests. Clear-cutting is an example of a man-made disturbance. Measures such as prescribed burning have been made to resemble natural disturbances. The aim of this study was to see which clear-cut characteristics are important for the occurrence of the saproxylic beetle Upis ceramboides. This is a species favored by open habitats and is said to respond positively to forest fires. The distribution area in Sweden for this species has decreased during the last two centuries and I wanted to see if there were differences between clear-cuts in Hälsingland, where it is very rare and decreasing, and Norrbotten where this study was conducted. -

Bee-Plant Networks: Structure, Dynamics and the Metacommunity Concept

Ber. d. Reinh.-Tüxen-Ges. 28, 23-40. Hannover 2016 Bee-plant networks: structure, dynamics and the metacommunity concept – Anselm Kratochwil und Sabrina Krausch, Osnabrück – Abstract Wild bees play an important role within pollinator-plant webs. The structure of such net- works is influenced by the regional species pool. After special filtering processes an actual pool will be established. According to the results of model studies these processes can be elu- cidated, especially for dry sandy grassland habitats. After restoration of specific plant com- munities (which had been developed mainly by inoculation of plant material) in a sandy area which was not or hardly populated by bees before the colonization process of bees proceeded very quickly. Foraging and nesting resources are triggering the bee species composition. Dis- persal and genetic bottlenecks seem to play a minor role. Functional aspects (e.g. number of generalists, specialists and cleptoparasites; body-size distributions) of the bee communities show that ecosystem stabilizing factors may be restored rapidly. Higher wild-bee diversity and higher numbers of specialized species were found at drier plots, e.g. communities of Koelerio-Corynephoretea and Festuco-Brometea. Bee-plant webs are highly complex systems and combine elements of nestedness, modularization and gradients. Beside structural com- plexity bee-plant networks can be characterized as dynamic systems. This is shown by using the metacommunity concept. Zusammenfassung: Wildbienen-Pflanzenarten-Netzwerke: Struktur, Dynamik und das Metacommunity-Konzept. Wildbienen spielen eine wichtige Rolle innerhalb von Bestäuber-Pflanzen-Netzwerken. Ihre Struktur wird vom jeweiligen regionalen Artenpool bestimmt. Nach spezifischen Filter- prozessen bildet sich ein aktueller Artenpool. -

Use of Human-Made Nesting Structures by Wild Bees in an Urban Environment

J Insect Conserv DOI 10.1007/s10841-016-9857-y ORIGINAL PAPER Use of human-made nesting structures by wild bees in an urban environment 1 1,2 1,2 3 Laura Fortel • Mickae¨l Henry • Laurent Guilbaud • Hugues Mouret • Bernard E. Vaissie`re1,2 Received: 25 October 2015 / Accepted: 7 March 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Most bees display an array of strategies for O. bicornis showed a preference for some substrates, namely building their nests, and the availability of nesting resources Acer sp. and Catalpa sp. In a context of increasing urban- plays a significant role in organizing bee communities. ization and declining bee populations, much attention has Although urbanization can cause local species extinction, focused upon improving the floral resources available for many bee species persist in urbanized areas. We studied the bees, while little effort has been paid to nesting resources. response of a bee community to winter-installed human- Our results indicate that, in addition to floral availability, made nesting structures (bee hotels and soil squares, i.e. nesting resources should be taken into account in the 0.5 m deep holes filled with soil) in urbanized sites. We development of urban green areas to promote a diverse bee investigated the colonization pattern of these structures over community. two consecutive years to evaluate the effect of age and the type of substrates (e.g. logs, stems) provided on colonization. Keywords Wild bees Á Nesting resource availability Á Overall, we collected 54 species. In the hotels, two gregari- Nest-site fidelity Á Phylopatry Á Nest-site selection Á ous species, Osmia bicornis L. -

Kew Science Publications for the Academic Year 2017–18

KEW SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2017–18 FOR THE ACADEMIC Kew Science Publications kew.org For the academic year 2017–18 ¥ Z i 9E ' ' . -,i,c-"'.'f'l] Foreword Kew’s mission is to be a global resource in We present these publications under the four plant and fungal knowledge. Kew currently has key questions set out in Kew’s Science Strategy over 300 scientists undertaking collection- 2015–2020: based research and collaborating with more than 400 organisations in over 100 countries What plants and fungi occur to deliver this mission. The knowledge obtained 1 on Earth and how is this from this research is disseminated in a number diversity distributed? p2 of different ways from annual reports (e.g. stateoftheworldsplants.org) and web-based What drivers and processes portals (e.g. plantsoftheworldonline.org) to 2 underpin global plant and academic papers. fungal diversity? p32 In the academic year 2017-2018, Kew scientists, in collaboration with numerous What plant and fungal diversity is national and international research partners, 3 under threat and what needs to be published 358 papers in international peer conserved to provide resilience reviewed journals and books. Here we bring to global change? p54 together the abstracts of some of these papers. Due to space constraints we have Which plants and fungi contribute to included only those which are led by a Kew 4 important ecosystem services, scientist; a full list of publications, however, can sustainable livelihoods and natural be found at kew.org/publications capital and how do we manage them? p72 * Indicates Kew staff or research associate authors. -

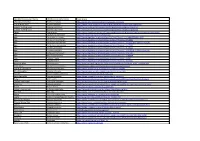

The PDF, Here, Is a Full List of All Mentioned

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

(Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains in Northern Michigan

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 19 Number 3 - Fall 1986 Number 3 - Fall 1986 Article 3 October 1986 Ecology of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains in Northern Michigan D. C. L. Gosling Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Gosling, D. C. L. 1986. "Ecology of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains in Northern Michigan," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 19 (3) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol19/iss3/3 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Gosling: Ecology of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains i 1986 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 153 ECOLOGY OF THE CERAMBYCIDAE (COLEOPTERA) OF THE HURON MOUNTAINS IN NORTHERN MICHIGAN D. C. L Gosling! ABSTRACT Eighty-nine species of Cerambycidae were collected during a five-year survey of the woodboring beetle fauna of the Huron Mountains in Marquette County, Michigan. Host plants were deteTITIined for 51 species. Observations were made of species abundance and phenology, and the blossoms visited by anthophilous cerambycids. The Huron Mountains area comprises approximately 13,000 ha of forested land in northern Marquette County in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. More than 7000 ha are privately owned by the Huron Mountain Club, including a designated, 2200 ha, Nature Research Area. The variety of habitats combines with differences in the nature and extent of prior disturbance to produce an exceptional diversity of forest communities, making the area particularly valuable for studies of forest insects. -

The Shared Microbiome of Bees and Flowers

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect (More than) Hitchhikers through the network: The shared microbiome of bees and flowers 1,2,8 3,8 Alexander Keller , Quinn S McFrederick , 4 4,5 6 Prarthana Dharampal , Shawn Steffan , Bryan N Danforth and 7 Sara D Leonhardt Growing evidence reveals strong overlap between production, biodiversity, and ecosystem functions. There- microbiomes of flowers and bees, suggesting that flowers are fore, hubs of microbial transmission. Whether floral transmission is pollination is an intensively studied research field. One the main driver of bee microbiome assembly, and whether emerging facet is the interaction of bees and plants with functional importance of florally sourced microbes shapes bee microbes [1,2]. Microbes can contribute positively or nega- foraging decisions are intriguing questions that remain tively to host health, development and fecundity.Detrimen- unanswered. We suggest that interaction network properties, tal effects on bees and plants are caused by pathogens and such as nestedness, connectedness, and modularity, as well competitors, while beneficial symbionts affect nutrition, as specialization patterns can predict potential transmission detoxification, and pathogen defense [1,2]. Insights into routes of microbes between hosts. Yet microbial filtering by the occurrence, nature, and implications of these associations plant and bee hosts determines realized microbial niches. strongly contribute to our understanding of the current risk Functionally, shared floral microbes can provide benefits for factors threatening bee and plant populations. bees by enhancing nutritional quality, detoxification, and disintegration of pollen. Flower microbes can also alter the Microbe-host associations in pollination systems are how- attractiveness of floral resources. Together, these mechanisms ever not isolated, but embedded in complex and multi- may affect the structure of the flower-bee interaction network. -

(Insects). Note 1

Muzeul Olteniei Craiova. Oltenia. Studii úi comunicări. ùtiinĠele Naturii. Tom. 29, No. 2/2013 ISSN 1454-6914 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE KNOWLEDGE OF RESEARCH ON BEETLE PARASITE FAUNA (INSECTS). NOTE 1. LILA Gima Abstract. The paper presents a synthesis of the data on the parasite fauna of longhorn beetles taken from papers published between 1959 and 2009 ((CONSTANTINEANU, 1959; PANIN &SĂVULESCU, 1961; BALTHASAR, 1963; TUDOR, 1969; PISICĂ, 2001; PISICĂ &POPESCU, 2009) and abroad, between 1945-1966 (GYORFI, 1945-1947; BALACHOWSKY, 1962-1963; HURPIN 1962 - for parasites and parasitoids species found in species of beetles and GRASSE 1953 and KUDO 1966 - to protozoa (Protozoa, sporozoite Gregarinomorpha) parasitic on beetles). In conclusion, beetles are host species for bacteria, protozoa, fungi, nematodes, mites, Hymenoptera and Diptera. To complete data about parasite fauna beetles still will consult other papers from country and from abroad. Keywords: parasites, parasitoids, beetle-host. Rezumat. ContribuĠii la cunoaúterea cercetărilor privind parazitofauna la coleoptere (Insecta). Lucrarea prezintă o sinteză a datelor referitoare la parazitofauna unor specii de coleoptere preluate din lucrări publicate pentru România între 1959-2009 (CONSTANTINEANU, 1959; PANIN &SĂVULESCU, 1961; BALTHASAR, 1963; TUDOR, 1969; PISICĂ, 2001; PISICĂ &POPESCU, 2009) úi pentru străinătate între 1945-1966 (GYORFI, 1945-1947; BALACHOWSKY, 1962-1963; HURPIN 1962 pentru paraziĠi úi parazitoizi găsiĠi la specii de coleoptere precum úi GRASSE 1953 úi KUDO 1966, pentru protozoare parazite la diverse specii de coleoptere). În concluzie, gândaci sunt specii gazdă pentru bacterii, protozoare, ciuperci, nematode, acarieni, hymenoptere úi diptere. Pentru a avea date cât mai complete despre parazitofauna la coleoptere, în continuare vom consulta úi alte lucrări de specialitate din Ġarӽ cât úi din strӽinătate.