Use of Human-Made Nesting Structures by Wild Bees in an Urban Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Megachile (Callomegachile) Sculpturalis Smith, 1853 (Apoidea: Megachilidae): a New Exotic Species in the Iberian Peninsula, and Some Notes About Its Biology

Butlletí de la Institució Catalana d’Història Natural, 82: 157-162. 2018 ISSN 2013-3987 (online edition): ISSN: 1133-6889 (print edition)157 GEA, FLORA ET fauna GEA, FLORA ET FAUNA Megachile (Callomegachile) sculpturalis Smith, 1853 (Apoidea: Megachilidae): a new exotic species in the Iberian Peninsula, and some notes about its biology Oscar Aguado1, Carlos Hernández-Castellano2, Emili Bassols3, Marta Miralles4, David Navarro5, Constantí Stefanescu2,6 & Narcís Vicens7 1 Andrena Iniciativas y Estudios Medioambientales. 47007 Valladolid. Spain. 2 CREAF. 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès. Spain. 3 Parc Natural de la Zona Volcànica de la Garrotxa. 17800 Olot. Spain. 4 Ajuntament de Sant Celoni. Bruc, 26. 08470 Sant Celoni. Spain. 5 Unitat de Botànica. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès. Spain. 6 Museu de Ciències Naturals de Granollers. 08402 Granollers. Spain. 7 Servei de Medi Ambient. Diputació de Girona. 17004 Girona. Spain. Corresponding author: Oscar Aguado. A/e: [email protected] Rebut: 20.09.2018; Acceptat: 26.09.2018; Publicat: 30.09.2018 Abstract The exotic bee Megachile sculpturalis has colonized the European continent in the last decade, including some Mediterranean countries such as France and Italy. In summer 2018 it was recorded for the first time in Spain, from several sites in Catalonia (NE Iberian Peninsula). Here we give details on these first records and provide data on its biology, particularly of nesting and floral resources, mating behaviour and interactions with other species. Key words: Hymenoptera, Megachilidae, Megachile sculpturalis, exotic species, biology, Iberian Peninsula. Resum Megachile (Callomegachile) sculpturalis Smith, 1853 (Apoidea: Megachilidae): una nova espècie exòtica a la península Ibèrica, amb notes sobre la seva biologia L’abella exòtica Megachile sculpturalis ha colonitzat el continent europeu en l’última dècada, incloent alguns països mediterranis com França i Itàlia. -

Torix Rickettsia Are Widespread in Arthropods and Reflect a Neglected Symbiosis

GigaScience, 10, 2021, 1–19 doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab021 RESEARCH RESEARCH Torix Rickettsia are widespread in arthropods and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/gigascience/article/10/3/giab021/6187866 by guest on 05 August 2021 reflect a neglected symbiosis Jack Pilgrim 1,*, Panupong Thongprem 1, Helen R. Davison 1, Stefanos Siozios 1, Matthew Baylis1,2, Evgeny V. Zakharov3, Sujeevan Ratnasingham 3, Jeremy R. deWaard3, Craig R. Macadam4,M. Alex Smith5 and Gregory D. D. Hurst 1 1Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Liverpool, Leahurst Campus, Chester High Road, Neston, Wirral CH64 7TE, UK; 2Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, University of Liverpool, 8 West Derby Street, Liverpool L69 7BE, UK; 3Centre for Biodiversity Genomics, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Road East, Guelph, Ontario N1G2W1, Canada; 4Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust, Balallan House, 24 Allan Park, Stirling FK8 2QG, UK and 5Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Summerlee Science Complex, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, Canada ∗Correspondence address. Jack Pilgrim, Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. E-mail: [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2941-1482 Abstract Background: Rickettsia are intracellular bacteria best known as the causative agents of human and animal diseases. Although these medically important Rickettsia are often transmitted via haematophagous arthropods, other Rickettsia, such as those in the Torix group, appear to reside exclusively in invertebrates and protists with no secondary vertebrate host. Importantly, little is known about the diversity or host range of Torix group Rickettsia. -

Bees in the Genus Rhodanthidium. a Review and Identification

The genus Rhodanthidium is small group of pollinator bees which are found from the Moroccan Atlantic coast to the high mountainous areas of Central Asia. They include both small inconspicuous species, large species with an appearance much like a hornet, and vivid species with rich red colouration. Some of them use empty snail shells for nesting with a fascinating mating and nesting behaviour. This publication gives for the first time a complete Rhodanthidium overview of the genus, with an identification key, the first in the English language. All species are fully illustrated in both sexes with 178 photographs and 60 line drawings. Information is given on flowers visited, taxonomy, and seasonal occurrence; distribution maps are including for all species. This publication summarises our knowledge of this group of bees and aims at stimulating further Supplement 24, 132 Seiten ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. April 2019 research. Kasparek, Bees in the Genus Max Kasparek Bees in the Genus Rhodanthidium A Review and Identification Guide Entomofauna, Supplementum 24 ISSN 02504413 © Maximilian Schwarz, Ansfelden, 2019 Edited and Published by Prof. Maximilian Schwarz Konsulent für Wissenschaft der Oberösterreichischen Landesregierung Eibenweg 6 4052 Ansfelden, Austria EMail: [email protected] Editorial Board Fritz Gusenleitner, Biologiezentrum, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Linz Karin Traxler, Biologiezentrum, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Linz Printed by Plöchl Druck GmbH, 4240 Freistadt, Austria with 100 % renewable energy Cover Picture Rhodanthidium aculeatum, female from Konya province, Turkey Biologiezentrum, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Linz (Austria) Author’s Address Dr. Max Kasparek Mönchhofstr. 16 69120 Heidelberg, Germany Email: Kasparek@tonline.de Supplement 24, 132 Seiten ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. -

Estimating Potential Range Shift of Some Wild Bees in Response To

Rahimi et al. Journal of Ecology and Environment (2021) 45:14 Journal of Ecology https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-021-00189-8 and Environment RESEARCH Open Access Estimating potential range shift of some wild bees in response to climate change scenarios in northwestern regions of Iran Ehsan Rahimi1* , Shahindokht Barghjelveh1 and Pinliang Dong2 Abstract Background: Climate change is occurring rapidly around the world, and is predicted to have a large impact on biodiversity. Various studies have shown that climate change can alter the geographical distribution of wild bees. As climate change affects the species distribution and causes range shift, the degree of range shift and the quality of the habitats are becoming more important for securing the species diversity. In addition, those pollinator insects are contributing not only to shaping the natural ecosystem but also to increased crop production. The distributional and habitat quality changes of wild bees are of utmost importance in the climate change era. This study aims to investigate the impact of climate change on distributional and habitat quality changes of five wild bees in northwestern regions of Iran under two representative concentration pathway scenarios (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5). We used species distribution models to predict the potential range shift of these species in the year 2070. Result: The effects of climate change on different species are different, and the increase in temperature mainly expands the distribution ranges of wild bees, except for one species that is estimated to have a reduced potential range. Therefore, the increase in temperature would force wild bees to shift to higher latitudes. -

Bee-Plant Networks: Structure, Dynamics and the Metacommunity Concept

Ber. d. Reinh.-Tüxen-Ges. 28, 23-40. Hannover 2016 Bee-plant networks: structure, dynamics and the metacommunity concept – Anselm Kratochwil und Sabrina Krausch, Osnabrück – Abstract Wild bees play an important role within pollinator-plant webs. The structure of such net- works is influenced by the regional species pool. After special filtering processes an actual pool will be established. According to the results of model studies these processes can be elu- cidated, especially for dry sandy grassland habitats. After restoration of specific plant com- munities (which had been developed mainly by inoculation of plant material) in a sandy area which was not or hardly populated by bees before the colonization process of bees proceeded very quickly. Foraging and nesting resources are triggering the bee species composition. Dis- persal and genetic bottlenecks seem to play a minor role. Functional aspects (e.g. number of generalists, specialists and cleptoparasites; body-size distributions) of the bee communities show that ecosystem stabilizing factors may be restored rapidly. Higher wild-bee diversity and higher numbers of specialized species were found at drier plots, e.g. communities of Koelerio-Corynephoretea and Festuco-Brometea. Bee-plant webs are highly complex systems and combine elements of nestedness, modularization and gradients. Beside structural com- plexity bee-plant networks can be characterized as dynamic systems. This is shown by using the metacommunity concept. Zusammenfassung: Wildbienen-Pflanzenarten-Netzwerke: Struktur, Dynamik und das Metacommunity-Konzept. Wildbienen spielen eine wichtige Rolle innerhalb von Bestäuber-Pflanzen-Netzwerken. Ihre Struktur wird vom jeweiligen regionalen Artenpool bestimmt. Nach spezifischen Filter- prozessen bildet sich ein aktueller Artenpool. -

Kew Science Publications for the Academic Year 2017–18

KEW SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2017–18 FOR THE ACADEMIC Kew Science Publications kew.org For the academic year 2017–18 ¥ Z i 9E ' ' . -,i,c-"'.'f'l] Foreword Kew’s mission is to be a global resource in We present these publications under the four plant and fungal knowledge. Kew currently has key questions set out in Kew’s Science Strategy over 300 scientists undertaking collection- 2015–2020: based research and collaborating with more than 400 organisations in over 100 countries What plants and fungi occur to deliver this mission. The knowledge obtained 1 on Earth and how is this from this research is disseminated in a number diversity distributed? p2 of different ways from annual reports (e.g. stateoftheworldsplants.org) and web-based What drivers and processes portals (e.g. plantsoftheworldonline.org) to 2 underpin global plant and academic papers. fungal diversity? p32 In the academic year 2017-2018, Kew scientists, in collaboration with numerous What plant and fungal diversity is national and international research partners, 3 under threat and what needs to be published 358 papers in international peer conserved to provide resilience reviewed journals and books. Here we bring to global change? p54 together the abstracts of some of these papers. Due to space constraints we have Which plants and fungi contribute to included only those which are led by a Kew 4 important ecosystem services, scientist; a full list of publications, however, can sustainable livelihoods and natural be found at kew.org/publications capital and how do we manage them? p72 * Indicates Kew staff or research associate authors. -

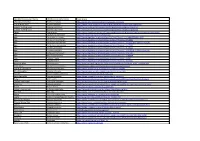

The PDF, Here, Is a Full List of All Mentioned

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

Machine Learning and Pollination Networks: the Right Flower for Every Bee

MACHINE LEARNING AND POLLINATION NETWORKS: THE RIGHT FLOWER FOR EVERY BEE Aantal woorden: 31 707 Sarah Vanbesien Studentennummer: 01300049 Promotor: prof. dr. Bernard De Baets Copromotor: prof. dr. ir. Guy Smagghe Tutor(s): dr. ir. Michiel Stock, ir. Niels Piot Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad: master in de richting Bio-ingenieurswetenschappen: Milieutechnologie. Academiejaar: 2017 - 2018 De auteur en promotor geven de toelating deze scriptie voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen en delen ervan te kopiëren voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting uitdrukkelijk de bron te vermelden bij het aanhalen van resultaten uit deze scriptie. The author and promoter give the permission to use this thesis for consultation and to copy parts of it for personal use. Every other use is subject to the copyright laws, more specifically the source must be extensively specified when using results from this thesis. Ghent, June 8, 2018 The promoter, The copromoter, prof. dr. Bernard De Baets prof. dr. ir. Guy Smagghe The tutor, The tutor, The author, dr. ir. Michiel Stock ir. Niels Piot Sarah Vanbesien 4 DANKWOORD ’Oh, een thesis over bloemetjes en bijtjes?’ Het wekt initieël toch net iets senuelere gedachten op dan nodig. Je zou denken dat er wanneer je dan de minder sexy kant van je onderzoek begint uit te leggen veel mensen afhaken, en wel, dat klopt. Gelukkig zit ik in een vakgroep vol mensen die formules en modelleren even interes- sant vinden als ik. Allereerst mijn tutor Michiel, naar jou gaat zonder twijfel mijn grootste dank uit! Iedere dag stond je klaar om mijn ontelbare vragen te beantwoorden. -

The Shared Microbiome of Bees and Flowers

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect (More than) Hitchhikers through the network: The shared microbiome of bees and flowers 1,2,8 3,8 Alexander Keller , Quinn S McFrederick , 4 4,5 6 Prarthana Dharampal , Shawn Steffan , Bryan N Danforth and 7 Sara D Leonhardt Growing evidence reveals strong overlap between production, biodiversity, and ecosystem functions. There- microbiomes of flowers and bees, suggesting that flowers are fore, hubs of microbial transmission. Whether floral transmission is pollination is an intensively studied research field. One the main driver of bee microbiome assembly, and whether emerging facet is the interaction of bees and plants with functional importance of florally sourced microbes shapes bee microbes [1,2]. Microbes can contribute positively or nega- foraging decisions are intriguing questions that remain tively to host health, development and fecundity.Detrimen- unanswered. We suggest that interaction network properties, tal effects on bees and plants are caused by pathogens and such as nestedness, connectedness, and modularity, as well competitors, while beneficial symbionts affect nutrition, as specialization patterns can predict potential transmission detoxification, and pathogen defense [1,2]. Insights into routes of microbes between hosts. Yet microbial filtering by the occurrence, nature, and implications of these associations plant and bee hosts determines realized microbial niches. strongly contribute to our understanding of the current risk Functionally, shared floral microbes can provide benefits for factors threatening bee and plant populations. bees by enhancing nutritional quality, detoxification, and disintegration of pollen. Flower microbes can also alter the Microbe-host associations in pollination systems are how- attractiveness of floral resources. Together, these mechanisms ever not isolated, but embedded in complex and multi- may affect the structure of the flower-bee interaction network. -

A Faunistic Study on Megachilidae (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of Northern Iran

Egypt. J. Plant Prot. Res. Inst. (2020), 3 (1): 398 - 408 Egyptian Journal of Plant Protection Research Institute www.ejppri.eg.net A faunistic study on Megachilidae (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of Northern Iran Hamid, Sakenin1; Shaaban, Abd-Rabou2; Nil, Bagriacik3; Majid, Navaeian4; Hassan, Ghahari4 and Siavash, Tirgari5 1Department of Plant Protection, Qaemshahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Mazandaran, Iran. 2Plant Protection Research Institute, Agricultural Reseach Center, Dokki, Giza, Egypt. 3 Niğde Omer Halisdemir University, Faculty of Science and Art, Department of Biology, 51100 Niğde Turkey. 4Faculty of Engineering, Yadegar- e- Imam Khomeini (RAH) Shahre Rey Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. 5Department of Entomology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. ARTICLE INFO Abstract: Article History In this faunistic research, totally 24 species of Received: 11/ 2/ 2020 Megachilidae (Hymenoptera) from 8 genera Anthidium Accepted: 20/ 3 /2020 Fabricius, 1805, Chelostoma Latreille, 1809, Coelioxys Keywords Latreille, 1809, Haetosmia Popov, 1952, Hoplitis Klug, 1807, Megachilidae, Apocrita, Lithurgus Berthold, 1827, Megachile Latreille, 1802, Osmia fauna, distribution and Panzer, 1806 were collected and identified from different Iran. regions of Iran. Two species are new records for the fauna of Iran: Coelioxys (Coelioxys) aurolimbata Förster, 1853, and Megachile (Eutricharaea) apicalis Spinola, 1808. Introduction Megachilidae (Hymenoptera) with belonging to the Megachilidae are more than 4000 described species effective pollinators in some plants worldwide (Michener, 2007) is a large (Bosch and Blas, 1994 and Vicens and family of specialized, morphologically Bosch, 2000). These solitary bees are rather uniform bees found in a wide both ecologically and economically diversity of habitats on all continents relevant; they include many pollinators of except Antarctica, ranging from lowland natural, urban and agricultural vegetation tropical rain forests to deserts to alpine (Gonzalez et al., 2012). -

Zweitfund Der Wespenbiene Nomada Stoeckherti Pittioni, 1951

©Ampulex online, Christian Schmid-Egger; download unter http://www.ampulex.de oder www.zobodat.at Witt & Schmalz: Zweitfund von Nomada stoeckhertiin Deutschland AMPULEX 10|2018 Zweitfund der Wespenbiene Nomada stoeckherti Pittioni, 1951 in Deutschland (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) Rolf Witt1, Karl-Heinz Schmalz2 1 Friedrichsfehner Straße 39 | 26188 Edewecht | Germany | [email protected] 2 Turmstraße 45 | 36124 Eichenzell | Germany | [email protected] Zusammenfassung Von der Zweizelligen Wespenbiene Nomada stoeckherti Pittioni, 1951 konnte 2016 aus einem Steinbruch bei Fulda der zweite Nach- weis für Deutschland und Erstnachweis für Hessen erbracht werden. Der Erstfund der Art für Deutschland stammt aus dem Jahr 2005. Potentielle Wirtsarten aus der Andrena minutula-Gruppe werden diskutiert. Summary Rolf Witt & Karl-Heinz Schmalz: Second record of the nomad bee Nomada stoeckherti Pittioni, 1951 for Germany (Hymenoptera: Anthophila). The second record for Germany of the nomad cuckoo bee Nomada stoeckherti Pittioni 1951 is reported from quarry near Fulda. This is also the first record for Hesse. The first record for Germany dated from 2005. Potential host species of the Andrena minutula-group are discussed. Einleitung te sehr zerstreute Funde aus der Slowakei, Ungarn, Ru- Für die Zweizellige Wespenbiene Nomada stoeckherti mänien, Bulgarien, Spanien (Andalusien), Griechenland Pittioni, 1951 lag bisher nur der Nachweis eines Weib- (Peleponnes, Kreta, Ägäis), Türkei, Israel und Algerien. chens aus dem Jahr 2007 vor. Esser (2008) meldete Die Art ist anhand ihrer zwei Cubitalzellen auch im Ge- die Art erstmals für Deutschland. Er fing das Tier eher lände gut zu bestimmen. Normalerweise wird auf die- zufällig während einer Pause am Rande einer Sandab- ses Merkmal bei der Gattung Nomada allerdings kaum baugrube bei Warnstedt am nördlichen Harzrand im geachtet, da die Flügeladerung zur Artdifferenzierung Rahmen einer anderweitigen Untersuchung (Esser, in der Gattung ansonsten kaum Relevanz hat. -

(Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Anthophila) in Serbia

ZooKeys 1053: 43–105 (2021) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.1053.67288 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Contribution to the knowledge of the bee fauna (Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Anthophila) in Serbia Sonja Mudri-Stojnić1, Andrijana Andrić2, Zlata Markov-Ristić1, Aleksandar Đukić3, Ante Vujić1 1 University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology and Ecology, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 2, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia 2 University of Novi Sad, BioSense Institute, Dr Zorana Đinđića 1, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia 3 Scientific Research Society of Biology and Ecology Students “Josif Pančić”, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 2, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia Corresponding author: Sonja Mudri-Stojnić ([email protected]) Academic editor: Thorleif Dörfel | Received 13 April 2021 | Accepted 1 June 2021 | Published 2 August 2021 http://zoobank.org/88717A86-19ED-4E8A-8F1E-9BF0EE60959B Citation: Mudri-Stojnić S, Andrić A, Markov-Ristić Z, Đukić A, Vujić A (2021) Contribution to the knowledge of the bee fauna (Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Anthophila) in Serbia. ZooKeys 1053: 43–105. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1053.67288 Abstract The current work represents summarised data on the bee fauna in Serbia from previous publications, collections, and field data in the period from 1890 to 2020. A total of 706 species from all six of the globally widespread bee families is recorded; of the total number of recorded species, 314 have been con- firmed by determination, while 392 species are from published data. Fourteen species, collected in the last three years, are the first published records of these taxa from Serbia:Andrena barbareae (Panzer, 1805), A.