Volume 310, No. 3 Opinions Filed in October-December 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

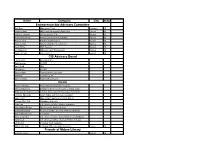

CARES Fund Disbursement Detailed

THE HOLTON INSIDE SALUTE GOFF, KAN. Enter this Hometown of week’s Football Max Niehues Pick’em Holton Recorder subscriber Contest! for 14 years. RECORDERServing the Jackson County Community for 153 years See pages 6A-7A. Volume 153, Issues 81 & 82 HOLTON, KANSAS • Mon./Wed. Oct. 12 & 14, 2020 26 Pages $1.00 CARES fund New flagpole up at Linscott Park By Brian Sanders Many young people in the disbursement Holton school district took ad- vantage of a day off on Mon- day for staff develop ment — some could be found taking detailed advantage of the play area at Linscott Park that afternoon. By Ali Holcomb the polling location was moved In another part of the park, Funds from Jackson Coun- to the Royal Valley Elementary a Holton High School student ty’s $2.9 million share of the School gym. spent Columbus Day involved Coronavirus Aid Relief and Eco- Members of the Hoyt City in hoisting a new, 30-foot flag- nomic Security (CARES) Act Council sought CARES Act pole between the two military have been allocated to a variety funds from the county to help monuments located at the of businesses, school districts, remedy the issue. park, with some help from the organizations and projects, but A total of $40,000 in CARES city’s electrical distribution not everyone is happy with their Act funds were allocated and depart ment and others. share. divided up between each of the The flagpole is one part of a During the Hoyt City Council county’s nine towns, and dis- three-part Eagle Scout project meeting last week, which was bursements included: undertaken -

Seeing the Future of Child Support with Open Eyes by Bethany Roberts and Casey E

Your Partner in the Profession | July/August 2020 • Vol. 89 • No. 6 Cigarettes and Tobacco Sale and Use Case: City Home Rule Prevails by Mike Heim P. 26 Kansas Child Support 2020: Seeing the Future of Child Support with Open Eyes by Bethany Roberts and Casey E. Forsyth P. 36 Mira Mdivani Charles E. Branson KBA Immediate Past President KBA President 2020-2021 POWERING PAYMENTS FOR THE Trust Payment IOLTA Deposit Amount LEGAL $ 1,500.00 INDUSTRY Reference The easiest way to accept credit card NEW CASE and eCheck payments online. Card Number **** **** **** 4242 Powerful Technology Developed specifically for the legal industry to ensure comprehensive security and trust account compliance Powering Law Firms Plugs into law firms’ existing workflows to drive cash flow, reduce collections, and make it easy for clients to pay Powering Integrations The payment technology behind the legal industry’s most popular practice management tools Powered by an Unrivaled Track Record 15 years of experience and the only payment technology vetted and approved by 110+ state, local, and specialty bars as well as the ABA ACCEPT MORE PAYMENTS WITH LAWPAY 888-281-8915 | lawpay.com/ksbar POWERING PAYMENTS 26 | Cigarette and Tobacco Sale and Use Case: FOR THE City Home Rule Prevails by Mike Heim Trust Payment IOLTA Deposit 36 | Kansas Child Support 2020: Seeing the Future Amount LEGAL of Child Support with Open Eyes by Bethany Roberts and Casey E. Forsyth $ 1,500.00 INDUSTRY Reference Cover Design by Ryan Purcell The easiest way to accept credit card NEW CASE and eCheck payments online. Special Features Card Number 11 | Kansas Bar Foundation Fellows Recognition (as of June 2020) .................................. -

2020 KBA Awards Avoiding a Quagmire

Your Partner in the Profession | September/October 2020 • Vol. 89 • No. 7 2020 KBA Awards P. 14 Avoiding a Quagmire: Acquiescence in a Judgment as a Bar to Appeal by Casey R. Law P. 30 POWERING PAYMENTS FOR THE Trust Payment IOLTA Deposit Amount LEGAL $ 1,500.00 INDUSTRY Reference The easiest way to accept credit, NEW CASE debit, and eCheck payments Card Number **** **** **** 4242 The ability to accept payments online has become vital for all firms. When you need to get it right, trust LawPay's proven solution. As the industry standard in legal payments, LawPay is the only payment solution vetted and approved by all 50 state bar associations, 60+ local and specialty bars, the ABA, and the ALA. Developed specifically for the legal industry to ensure trust account compliance and deliver the most secure, PCI-compliant technology, LawPay is proud to be the preferred, long-term payment partner for more than 50,000 law firms. ACCEPT MORE PAYMENTS WITH LAWPAY 888-281-8915 | lawpay.com/ksbar POWERING PAYMENTS FOR THE 14 | KBA Awards Trust Payment 30 | Avoiding a Quagmire: Acquiescence in a IOLTA Deposit Judgment as a Bar to Appeal by Casey R. Law Amount LEGAL $ 1,500.00 INDUSTRY Reference Cover Design by Ryan Purcell The easiest way to accept credit, NEW CASE debit, and eCheck payments Special Features Card Number 23 | KBA’s Virtual Annual Meeting—Literally FABULOUS ........................... **** **** **** 4242 The ability to accept payments online has Karla Whitaker become vital for all firms. When you need to 44 | Washburn Law Clinic: Clinic in the Time of Coronavirus...................Michelle Y. -

Selection to the Kansas Supreme Court

Selection to the Kansas Supreme Court by Stephen J. Ware NOVEMBER KANSAS 2007 ABOUT THE FEDERALIST SOCIETY Th e Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies is an organization of 40,000 lawyers, law students, scholars, and other individuals, located in every state and law school in the nation, who are interested in the current state of the legal order. Th e Federalist Society takes no position on particular legal or public policy questions, but is founded on the principles that the state exists to preserve freedom, that the separation of governmental powers is central to our constitution, and that it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be. Th e Federalist Society takes seriously its responsibility as a non-partisan institution engaged in fostering a serious dialogue about legal issues in the public square. We occasionally produce “white papers” on timely and contentious issues in the legal or public policy world, in an eff ort to widen understanding of the facts and principles involved, and to continue that dialogue. Positions taken on specifi c issues in publications, however, are those of the author, and not refl ective of an organization stance. Th is paper presents a number of important issues, and is part of an ongoing conversation. We invite readers to share their responses, thoughts and criticisms by writing to us at [email protected], and, if requested, we will consider posting or airing those perspectives as well. For more information about Th e Federalist Society, please visit our website: www.fed-soc.org. -

KANSAS POLICY REVIEW Policy Research Institute, the University of Kansas KPR KANSAS POLICY REVIEW Vol

Policy Research Institute KANSAS POLICY REVIEW Policy Research Institute, The University of Kansas KPR KANSAS POLICY REVIEW Vol. 27, No. 2 Fall 2005 SPECIAL ISSUE: From the Editor Perspectives on School Finance in Kansas Bruce D. Baker, Guest Editor Public K-12 education is by far the single From the Editor ........................................................... 1 Joshua L. Rosenbloom largest program funded by the State General Joshua Rosenbloom is Professor of History and Economics Fund in Kansas. Over the past decade few issues and Director of the Center for Economic and Business have been as contentious in state policy. During Analysis at the Policy Research Institute, University of Kansas. 2005 the adequacy of the state’s funding as well as the way that funds are distributed across History of School Finance Reform and Litigation in Kansas ............................................ 2 districts resulted in a stand-off between the State Bruce D. Baker Supreme Court and the Legislature. With these Preston C. Green, III issues in mind I asked Professor Bruce Baker if Bruce D. Baker is Associate Professor of Teaching and Leadership at the University of Kansas. He is lead author of he would edit a special issue of the Kansas Financing Education Systems under contract with Merrill/ Prentice-Hall, and author of over 30 articles since 1998 in Policy Review devoted to an analysis of the journals including the Economics of Education Review, legal, economic, political, and educational Journal of Education Finance, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, and American Journal of Education. He has dimensions of this controversy. Professor Baker consulted for the Texas, Missouri, and Wyoming legislatures has done an excellent job, assembling a set of on the design of school finance policy and has served as an expert witness on school finance cases in Kansas and articles that clearly explain the history of the Nebraska. -

August 6, 2020 Honorable Nathan L. Hecht President, Conference Of

August 6, 2020 Honorable Nathan L. Hecht President, Conference of Chief Justices c/o Association and Conference Services 300 Newport Avenue Williamsburg, VA 23185-4147 RE: Bar Examinations and Lawyer Licensing During the COVID-19 Pandemic Dear Chief Justice Hecht: On behalf of the American Bar Association (ABA), the largest voluntary association of lawyers and legal professionals in the world, I write to urge the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) to prioritize the development of a national strategy for bar examinations and lawyer licensing for the thousands of men and women graduating law school during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a temporary change and only as necessary to address the public health and safety issues presented during this crisis without closing the doors to our shared profession. In particular, we recommend that this national strategy urge each jurisdiction to cancel in-person bar examinations during the pandemic unless they can be administered in a safe manner; establish temporary measures to expeditiously license recent law school graduates and other bar applicants; and enact certain practices with respect to the administration of remote bar examinations. We appreciate that some jurisdictions may have already taken some action, such as modifying the bar examination dates or setting or temporarily modifying their admission or practice rules. But the failure of all jurisdictions to take appropriate action presents a crisis for the future of the legal profession that will only cascade into future years. Earlier this week, the ABA House of Delegates discussed this important subject and heard from many different stakeholders within the legal profession, including concerns from the National Conference of Bar Examiners. -

Politics of Judicial Elections 2015 16

THE POLITICS OF JUDICIAL ELECTIONS 201516 Who Pays for Judicial Races? By Alicia Bannon, Cathleen Lisk, and Peter Hardin With Douglas Keith, Laila Robbins, Eric Velasco, Denise Roth Barber, and Linda Casey Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law National Institute on Money and State Politics CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter One: Supreme Court Election Spending Reaches New Heights 4 Spending Overview: 2015-16 Supreme Court Election Cycle 4 Notable Trends: Secret Money and Record Outside Spending 7 Profiled Races: What Factors Contribute to High-Cost Elections? 12 The Bigger Picture: Big Money Races Leave A Mark On A Majority of Elected Courts 15 State Courts as Political Targets 19 Chapter Two: A Closer Look at Interest Groups 21 Overview 21 The Transparency Problem 22 Wisconsin’s Weak Recusal Standards Undermine Fair Courts 26 The Major Players 27 A Parallel Problem: Dark Money and Judicial Nominations 30 Chapter 3: Television Ads and the Politicization of Supreme Court Races 32 Overview 32 A More Pervasive Negative Tone 33 Ad Themes 36 Ad Spotlight 38 Conclusion 40 Appendix 42 IV CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES Introduction Chapter One Estimated Spending on State Supreme Court Races, 2015-16 5 Number of Judges Elected in $1 Million-Plus Elections by Cycle 6 State Supreme Court Election Spending by Cycle (2016 Dollars) 8 Outside Spending by Interest Groups (2016 Dollars) 9 Spending Breakdown for 2015-16 Supreme Court Races 9 Contributions to Candidates by Sector, 2015-16 11 Top 10 Candidate Fundraisers, 2015-16 11 The Rise of Million Dollar Courts 16 Million Dollar Courts in 2016 17 Chapter Two Top 10 Outside Spenders and Secret Money, 2015-16 23 Outside Group Spending: Dark, Gray, and Transparent Money, 2015-16 24 States with Unreported Outside Spending, 2015-16 25 Chapter 3 Total TV Spending, 2015-16 33 Number of Television Ad Spots by Cycle 34 Total TV Spending by Cycle (2016 Dollars) 34 Ad Tone Analysis: Groups vs. -

Kansas Supreme Court: Chief Justice Marla Luckert

Chief Justice Uniquely suited for current role, Luckert seizes historic opportunities. By Angela Lutz From her third-story office in the Kansas Judicial Center, to challenge people to do that investigation in all of their jobs Supreme Court Chief Justice Marla Luckert, BA ’71, JD ’80, in all aspects of the court system, and I hope we are all open to might just have the best view in Topeka. Outside the large seeing where that leads us.” plate-glass window behind her desk, the Kansas State Capitol sits proudly, its pointed, copper dome seeming to scrape the With a successful and varied legal career, Luckert is uniquely cloudless Midwestern sky. suited for her current role. Growing up in rural Kansas during the civil rights era, she knew she wanted to be a lawyer after “It’s a good reminder,” Luckert said, gazing at the iconic reading “To Kill a Mockingbird” in grade school. As soon as building. “I want to do everything I can for citizens of Kansas she could, she joined the debate team and began honing her to make access to justice more than just a statement that we research and analysis skills. After graduating from Washburn throw out. It’s something that’s real and meaningful.” University School of Law, she joined a Topeka firm where she specialized in health care law before being appointed to the Initially appointed to the Kansas Supreme Court by Gov. Shawnee County District Court in 1992. She served on the Bill Graves in 2002, Luckert was sworn in as chief justice district court bench for 10 years and became chief judge in last December. -

2016 State Supreme Courtelections

1 2016 State Supreme Court Elections # of Seats Date of Date of Available # of Primary General Type of for Contested # of Names of Primary Election Names of General Election State Election Election Election Election Seats Candidates Candidates Candidates Contested Partisan and Nonpartisan Elections Position 1: Michael F. "Mike" Bolin, Republican* Position 2: Position 3: Kelli Wise, Republican* Donna J. Beaulieu, Republican Position 3: AL Mar. 1, 2016 Nov. 8, 2016 Partisan 3 0 4 Tom Parker, Republican* Tom Parker, Republican* Chief Justice Seat: Courtney Goodson* Dan Kemp Position 5: No Primary Clark W. Mason AR Election Mar. 1, 2016 Nonpartisan 2 2 4 Not Applicable Shawn. A. Womack No General GA May 24, 2016 Election Nonpartisan 1 0 1 David Nahmias* Not Applicable Seat 1: Seat 1: Roger S. Burdick* Roger S. Burdick* Seat 2: Seat 2: Robyn Brody Robyn Brody Sergio A. Gutierrez Curt McKenzie Curt McKenzie ID May 17, 2016 Nov. 8, 2016 Nonpartisan 2 1 5 Clive J. Strong No Primary Larry VanMeter KY Election Nov. 8, 2016 Nonpartisan 1 1 2 Not Applicable Glenn Acree *—Incumbent Gray—Uncontested general election for all seats Green —Election has passed Bold—Winner 2 # of Seats Date of Date of Available # of Primary General Type of for Contested # of Names of Primary Election Names of General Election State Election Election Election Election Seats Candidates Candidates Candidates 3rd District Justice Marilyn Castle, Republican James “Jimmy” Genovese, Republican No General 4th District Judge LA Nov. 8, 2016 Election Partisan 2 1 3 Marcus Clark, Republican* Not Applicable Nonpartisan (candidates are Seat 1: nominated David Viviano, Republican* through a Doug Dern, Natural Law partisan Party process and Frank Szymanski, Democrat elected in a Seat 2: nonpartisan Joan Larsen, Republican* No Primary general Kerry Morgan, Liberal MI Election Nov. -

Washburn Lawyer, V. 41, No. 1

FA L L / W I N T E R WA S H B U R N 2 0 0 2 - 2 0 0 3 LawyerLawyer History of Women at Washburn Profiles of Women in Leadership Rising Stars Table of Contents THEME: Women at W a s h b u r n Jessie Nye F E A T U R E S : ■ History of Women at Washburn University School of Law – Professor Charlene Smith. .4-9 Copyright 2003, by the Washburn Profiles of Women in Leadership . 13 - 17 University School of Law. 5 Rising Stars . 18 - 20 All rights reserved. Donor Honor Roll . 27 - 35 Matt Memmer Washburn Lawyer is published D E P A R T M E N T S : semiannually by The Washburn Law Letter from the Dean . 3 School Alumni Association. Close-Up Editorial Office: C/O Washburn Matt Memmer (Student) . 21 University School of Law, Alumni Lillian G. Apodaca (Alumni). 22 Relations and Development Office, 21 Professor Loretta Moore (Faculty). 23 1700 SW College Avenue, Centers of Excellence Topeka, KS 66621. Business and Transactional Law Center . 10 Children and Family Law Center . 11 We welcome your responses to Center for Excellence in Advocacy . .12 this publication. Write to: Class Actions . .24 - 26 Editor: The Washburn Lawyer In Memoriam . 36 Washburn University News & Events . .37 - 39 School of Law Michael Manning Keynote Speaker . 37 Alumni Relations and Kansas Supreme Court Appointments . 37 Development Office Bianchino Technology Center Dedication . .38 1700 SW College Avenue Ahrens Genomic Tort Symposium . .38 Topeka, KS 66621 National Jurist Recognition . 39 Partnerships . .39 Or send E-mail to: Events Calendar . -

Counterbalance, Fall 2019, Volume 18, Issue 2

FALL 2019, Vol.18, Issue 2 FALL 2019 1 FALL 2019 2 MISSION NAWJ’s mission is to promote the judicial role of protecting the rights of individuals under the rule of law through strong, President’s Message committed, diverse judicial leadership; fairness and equality in the courts; and struggle of legal professionals facing sexual equal access to justice. 28 Second Annual Texas Law Day ear Members, ON THE COVER harassment in the workplace and provide NAtWJ Visits Vatican for 29 NAWJ’s Mimi Tsankov Leads I am honored to serve as your education and activism through #WeToo In BOARD OF DIRECTORS Pan-American Judges’ Summit on Celebration of International President and stay the course of the the Legal Workplace. Our ongoing EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Social Rights Women’s Day at Fordham impeccable leadership provided by Judge Tamila collaborations with Federal and State Courts PRESIDENT See article and photos on page 20 Ipema and all of our esteemed Past Presidents of fight to end human trafficking – modern day Hon. Bernadette D'Souza 2 President's Message 30 Project Access NAWJ. Stepping into this role, I am humbled by enslavement of women and vulnerable Parish of Orleans Civil District Court, Louisiana both the opportunity and responsibility of this communities. I look forward to bolstering PRESIDENT-ELECT 3 Immediate Past President's Message 32 A Look at NAWJ and the State of office and inspired by the passion, grace and these efforts through support and leadership Hon. Karen Donohue Women in the Legal Profession dedication of our leaders and membership. and will dedicate my term to seeking out King County Superior Court, Seattle, Washington 4 Interim Executive Director's through Our Past Presidents NAWJ provides a vital and unique source of further opportunities to expand our work to a VICE PRESIDENT, DISTRICTS Message community, support, diplomacy and integrity to global scale. -

Advisory Board

Name Company City State Entreprenurship Advisory Committee Dee Bisel Minuteman Press Lawrence KS Martha Piland MB Piland Advertising & Marketing Topeka KS Jeffrey L. Ungerer Jeffrey Ungerer, P.A. Topeka KS Kenneth Schmanke Kansas Commercial Real Estate Topeka KS Heather Gish Branded Clothing Store Topeka KS Tony Aufusto Topeka Chamber of Commerce Topeka KS Kevin Bittner KMC Telecom Topeka KS Jim Klausman Midwest Health Management Topeka KS Peter La Colla Street Corner Topeka KS CIS Advisory Board Tim Blevins KS Dept of Rev Bob Kennedy KS SRS Dave Keith SBG Gary Mcgirr KS SRS Steve Naylor Federal Home Loan Bank Bob Roth Capitol Federal Dave Vonfeldt Payless Shoe Source Victim Helen P. Bradley Victim-Witness Assistance Program Sharon D'Eusanio Dicision of Victim Services and Criminal Justice Anita Armstrong Drummond Criminal Justice and Victims Issues Consultant Christine Edmunds Victim Rights and Services Consultant Karin Ehlert Minnesota Department of Public Safety Richard Ellis, PhD Washburn University Joan Gay U.S. Attorney's Office, District of Kansas Kathy Manis-Findley The Center for Healing & Hope Sandra McGowan New Jersey Office of Victim-Witness Advocacy Sharon Montagnino Consultant Mary Jo Speaker U.S. Attorney's Office, Eastern District of Oklahoma Kathi West U.S. Attorney's Office, Western District of Texas Jill Weston California Youth Authority Arthur V.N. Wint California State University at Fresno Fresno CA Friends of Mabee Library Betty M. Casper Topeka KS Wanda V. Dole Topeka KS Dorothy Hanger Topeka KS Marc Galbraith Topeka KS Ted Heim Topeka KS Rosemary Menninger Topeka KS Larry Peters Topeka KS Robert Richmond Topeka KS Marcia Saville Topeka KS Jim Sloan Topeka KS Warren Taylor Topeka KS Alice Young Topeka KS Friends of Washburn Music Charlotte Adair Blair Anderson Detria Anderson Marilyn Foree Norman Gamboa Kevin Kellim Melanie McQuere John Mullican Norma Pettijohn Anna rev Kirt Saville Ann Marie Snook Lee Snook Robert Webb Law Lillian A.