October 30, 2002 (227.02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Visualization of Geospatial Stream Data Using the Worldwide Telescope

Online Visualization of Geospatial Stream Data using the WorldWide Telescope Mohamed Ali#, Badrish Chandramouli*, Jonathan Fay*, Curtis Wong*, Steven Drucker*, Balan Sethu Raman# #Microsoft SQL Server, One Microsoft Way, Redmond WA 98052 {mali, sethur}@microsoft.com *Microsoft Research, One Microsoft Way, Redmond WA 98052 {badrishc, jfay, curtis.wong, sdrucker}@microsoft.com ABSTRACT execution query pipeline. StreamInsight has been used in the past This demo presents the ongoing effort to meld the stream query to process geospatial data, e.g., in traffic monitoring [4, 5]. processing capabilities of Microsoft StreamInsight with the On the other hand, the WorldWide Telescope (WWT) [9] enables visualization capabilities of the WorldWide Telescope. This effort a computer to function as a virtual telescope, bringing together provides visualization opportunities to manage, analyze, and imagery from the various ground and space-based telescopes in process real-time information that is of spatio-temporal nature. the world. WWT enables a wide range of user experiences, from The demo scenario is based on detecting, tracking and predicting narrated guided tours from astronomers and educators featuring interesting patterns over historical logs and real-time feeds of interesting places in the sky, to the ability to explore the features earthquake data. of planets. One interesting feature of WWT is its use as a 3-D model of earth, enabling its use as an earth viewer. 1. INTRODUCTION Real-time stream data acquisition has been widely used in This demo presents the ongoing work at Microsoft Research and numerous applications such as network monitoring, Microsoft SQL Server groups to meld the value of stream query telecommunications data management, security, manufacturing, processing of StreamInsight with the unique visualization and sensor networks. -

Seeing the Sky Visualization & Astronomers

Seeing the Sky Visualization & Astronomers Alyssa A. Goodman Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics & Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study @aagie WorldWide Telescope Gm1m2 F= gluemultidimensional data exploration R2 Cognition “Paper of the Future” Language* Data Pictures Communication *“Language” includes words & math Why Galileo is my Hero Explore-Explain-Explore Notes for & re-productions of Siderius Nuncius 1610 WorldWide Telescope Galileo’s New Order, A WorldWide Telescope Tour by Goodman, Wong & Udomprasert 2010 WWT Software Wong (inventor, MS Research), Fay (architect, MS Reseearch), et al., now open source, hosted by AAS, Phil Rosenfield, Director see wwtambassadors.org for more on WWT Outreach WorldWide Telescope Galileo’s New Order, A WorldWide Telescope Tour by Goodman, Wong & Udomprasert 2010 WWT Software Wong (inventor, MS Research), Fay (architect, MS Reseearch), et al., now open source, hosted by AAS, Phil Rosenfield, Director see wwtambassadors.org for more on WWT Outreach Cognition “Paper of the Future” Language* Data Pictures Communication *“Language” includes words & math enabled by d3.js (javascript) outputs d3po Cognition Communication [demo] [video] Many thanks to Alberto Pepe, Josh Peek, Chris Beaumont, Tom Robitaille, Adrian Price-Whelan, Elizabeth Newton, Michelle Borkin & Matteo Cantiello for making this posible. 1610 4 Centuries from Galileo to Galileo 1665 1895 2009 2015 WorldWide Telescope Gm1m2 F= gluemultidimensional data exploration R2 WorldWide Telescope gluemultidimensional data exploration WorldWide Telescope gluemultidimensional data exploration Data, Dimensions, Display 1D: Columns = “Spectra”, “SEDs” or “Time Series” 2D: Faces or Slices = “Images” 3D: Volumes = “3D Renderings”, “2D Movies” 4D:4D Time Series of Volumes = “3D Movies” Data, Dimensions, Display Spectral Line Observations Loss of 1 dimension Mountain Range No loss of information Data, Dimensions, Display mm peak (Enoch et al. -

How Do Astronomers Share Data? Reliability and Persistence of Datasets Linked in AAS Publications and a Qualitative Study of Data Practices Among US Astronomers

How Do Astronomers Share Data? Reliability and Persistence of Datasets Linked in AAS Publications and a Qualitative Study of Data Practices among US Astronomers The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Pepe, Alberto, Alyssa Goodman, August Muench, Merce Crosas, and Christopher Erdmann. 2014. “How Do Astronomers Share Data? Reliability and Persistence of Datasets Linked in AAS Publications and a Qualitative Study of Data Practices among US Astronomers.” PLoS ONE 9 (8): e104798. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104798. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104798. Published Version doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104798 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12785853 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA How Do Astronomers Share Data? Reliability and Persistence of Datasets Linked in AAS Publications and a Qualitative Study of Data Practices among US Astronomers Alberto Pepe1,2*, Alyssa Goodman1,2, August Muench1, Merce Crosas2, Christopher Erdmann1 1 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America, 2 Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America Abstract We analyze data sharing practices of astronomers over the past fifteen years. An analysis of URL links embedded in papers published by the American Astronomical Society reveals that the total number of links included in the literature rose dramatically from 1997 until 2005, when it leveled off at around 1500 per year. -

Microsoft Protégé 2012 Case Study Brief OVERVIEW

Microsoft Protégé 2012 Case Study Brief OVERVIEW If you’re an Australian undergraduate Uni student, you’re eligible to enter the Microsoft Protégé Challenge. Your task is to show us how you would market Microsoft Kinect for Windows for use outside the gaming industry. This Case Study Brief gives you some background info, outlines the challenge and details the rules for entry. This is your chance to get your teeth into a real-life marketing challenge and gain experience that will make your CV stand out. And if you’re the Protégé 2012 Grand Prize winner, you’ll also score an amazing prize pack. BACKGROUND: THE KINECT EFFECT Headquartered in Redmond, USA, Microsoft Corporation gestures captured by the 3D sensor as well as the voice is one of the world’s largest technology companies and a commands captured by the microphone array from pioneer in software products for computing devices. someone much further away than someone using a headset or a phone. More importantly, Kinect software can In May 2005, Microsoft released the second iteration of its understand what each user means by a particular gesture hugely popular Xbox video game console, the Xbox 360. or command across a wide range of possible shapes, sizes, Helping the Xbox 360 in its success was the introduction of and actions of real people. Kinect, which became a gaming phenomenon overnight. People were inspired. Six months down the track, a diverse Through the magic of Kinect, controller-free games and group of hobbyists and academics from around the world entertainment – once the stuff of science fiction – had embraced the possibilities of using Kinect with their become a reality. -

A Satellite Constellation Visualization Program for Walkers and Lattice

BOUQUET: A SATELLITE CONSTELLATION VISUALIZATION PROGRAM FOR WALKERS AND LATTICE FLOWER CONSTELLATIONS A Thesis by MANDAKH ENKH Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2011 Major Subject: Aerospace Engineering Bouquet: A Satellite Constellation Visualization Program for Walkers and Lattice Flower Constellations Copyright 2011 Mandakh Enkh BOUQUET: A SATELLITE CONSTELLATION VISUALIZATION PROGRAM FOR WALKERS AND LATTICE FLOWER CONSTELLATIONS A Thesis by MANDAKH ENKH Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved by: Chair of Committee, Daniele Mortari Committee Members, John Hurtado John Junkins J. Maurice Rojas Head of Department, Dimitris Lagoudas August 2011 Major Subject: Aerospace Engineering iii ABSTRACT Bouquet: A Satellite Constellation Visualization Program for Walkers and Lattice Flower Constellations. (August 2011) Mandakh Enkh, B.S., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Daniele Mortari The development of the Flower Constellation theory offers an expanded framework to utilize constellations of satellites for tangible interests. To realize the full potential of this theory, the beta version of Bouquet was developed as a practical computer application that visualizes and edits Flower Constellations in a user-friendly manner. Programmed using C++ and OpenGL within the Qt software development environment for use on Windows systems, this initial version of Bouquet is capable of visualizing numerous user defined satellites in both 3D and 2D, and plot trajectories corresponding to arbitrary coordinate frames. The ultimate goal of Bouquet is to provide a viable open source alternative to commercial satellite orbit analysis programs. -

Presented by Alyssa Goodman, Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study

The Radcliffe Wave presented by Alyssa Goodman, Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study Nature paper by: João Alves1,3, Catherine Zucker2, Alyssa Goodman2,3, Joshua Speagle2, Stefan Meingast1, Thomas Robitaille4, Douglas Finkbeiner3, Edward Schlafly5 & Gregory Green6 representing (1) University of Vienna; (2) Harvard University; (3) Radcliffe Insitute; (4) Aperio Software; (5) Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; (6) Kavli Insitute for Particle Physics and Cosmology The Radcliffe Wave CARTOON* DATA *drawn by Dr. Robert Hurt, in collaboration with Milky Way experts based on data; as shown in screenshot from AAS WorldWide Telescope The Radcliffe Wave Each red dot marks a star-forming blob of gas whose distance from us has been accurately measured. The Radcliffe Wave is 9000 light years long, and 400 light years wide, with crest and trough reaching 500 light years out of the Galactic Plane. Its gas mass is more than three million times the mass of the Sun. video created by the authors using AAS WorldWide Telescope (includes cartoon Milky Way by Robert Hurt) The Radcliffe Wave ACTUALLY 2 IMPORTANT DEVELOPMENTS DISTANCES!! RADWAVE We can now Surprising wave- measure distances like arrangement to gas clouds in our of star-forming gas own Milky Way is the “Local Arm” galaxy to ~5% of the Milky Way. accuracy. Zucker et al. 2019; 2020 Alves et al. 2020 “Why should I believe all this?” DISTANCES!! We can now requires special measure distances regions on the Sky to gas clouds in our (HII regions own Milky Way with masers) galaxy to ~5% accuracy. can be used anywhere there’s dust & measurable stellar properties Zucker et al. -

Microsoft Research Worldwide Telescope Multi-Channel Dome/Frustum Setup Guide

Microsoft Research WorldWide Telescope Multi-Channel Dome/Frustum Setup Guide Prepared by Beau Guest & Doug Roberts Rev. 1.4, October 2013 WorldWide Telescope Multi-Channel Setup Guide Introduction Microsoft Research WorldWide Telescope (WWT) is a free program designed to give users the ability to explore the universe in a simple easy to use interface. Recently support has been developed to include a variety of playback mediums. This document will detail the steps required for a multi-channel display setup for use in a dome or frustum environment. It is recommended before attempting to setup a multi-channel system that you familiarize yourself with WWT as a system. There are many introductory tours that will help in this process that are included with the software. WWT is an ever evolving program and the steps, descriptions, and information contained in this guide is subject to change at any time. Parts of this guide work on the premise that you have the required data regarding projector positioning and field of view/aspect ratio. Please obtain these data before attempting to start this process. WWT is a trademark of Microsoft and all rights are reserved. 2 WorldWide Telescope Multi-Channel Setup Guide Table of Contents Software Installation ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 FOV Values ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Responding to the Event Deluge

Responding to the Event Deluge Roy D. Williams·, Scott D. Barthelmyb, Robert B. Dennyc, Matthew J. Graham', and John Swinbankd 'California Institute of Technology "NASA Goddard Space Flight Center 'DC-3 Dreams SP d University of Amsterdam ABSTRACT We present the VOEventNet infrastructure for large-scale rapid follow-up of astronomical events, including selection, annotation, machine intelligence, and coordination of observations. The VOEvent.standard is central to this vision, with distributed and replicated services rather than centralized facilities. We also describe some of the event brokers, services, and software that .are connected to the network. These technologies will become more important in the coming years, with new event streams from Gaia, LOFAR, LIGO, LSST, and many others. Keywords: VOEvent, GCN, TAN, Skyalert, transients 1. Deluge In the late 199Os, the gamma-ray burst (GRB) community ignited the current excitement over transient astronontical events. Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs) were a real enigma until ultra-fast event dissemination allowed optical identification of afterglOWS, leading to rich data and rich ·science. The events back then were both valuable and infrequent: every new ORB could make a career for a young astronomer, and they were only detected every few days. However, in the next few years, surveys carried out by telescopes sucb as Gaia, LOFAR, Pan-STARRS, LSST and SICA will produce a flood of hundreds of events every 24 hours, with the scientific jewels surrounded by dross, and so both scalability and discrimination will be increasingly important. We should also point out that a deluge of event metadata is also coming, as more transient surveys come online, and each of those spawns its own streams offollow-up events and annotations. -

The Work of Microsoft Research Connections in the Region

• To tell you more about Microsoft Research Connections • Global • EMEA • PhD Programme • Other engagements • • • Microsoft Research Connections Work broadly with the academic and research community to speed research, improve education, foster innovation and improve lives around the world. Accelerate university Support university research and research through education through collaborative technology partnerships investments Inspire the next Drive awareness generation of of Microsoft researchers and contributions scientists to research Engagement and Collaboration Focus Core Computer Natural User Earth Education and Health and Science Interface Energy Scholarly Wellbeing Environment Communication Research Accelerators Global Partnerships People • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Investment Focus Education & Earth, Energy, Health & Computer Science Scholarly and Environment Wellbeing Communication Programming, Natural User WW Telescope, Academic Search, MS Biology Tools, Mobile Interfaces Climate Change Digital Humanities, Foundation & Tools Earth Sciences Publishing Judith Bishop Kris Tolle Dan Fay Lee Dirks Simon Mercer Regional Outreach/Engagements EMEA: Fabrizio Gagliardi LATAM: Jaime Puente India: Vidya Natampally Asia: Lolan Song America/Aus/NZ: Harold Javid Engineering High-quality and high-impact software release and community adoption Derick Campbell CMIC EMIC ILDC • • . New member of MSR family • • • . Telecoms, Security, Online services and Entertainment Microsoft Confidential Regional Collaborations at Joint Institutes INRIA, FRANCE -

Scientific Workflow Workbench

Addressing World-Scale Challenges Computation as a powerful change agent in areas such as Energy, Environment, Healthcare, Education Collaboration and Community Massive amounts of data collected and aggregated from the internet, satellites, sensors, and other sources We need to move from data to knowledge Computing technologies are enabling Astronomy has been one of the first disciplines to embrace data-intensive science with the Virtual Observatory (VO), new approaches applied to world- enabling highly efficient access to data and analysis tools scale challenges in disciplines such at a centralized site. The image shows the as medicine and healthcare, energy Pleiades star cluster form the Digitized Sky Survey combined with an image of the moon, and the environment, educational and synthesized within the WorldWide Telescope service. social progress Research Councils UK Division within Microsoft Research focused on partnerships between academia, industry and government to advance computer science, education, and research in fields that rely heavily upon advanced computing Supporting groundbreaking research to help advance human potential and the wellbeing of our planet Developing advanced technologies and services to support every stage of the research process Microsoft External Research is committed to interoperability and to providing open access, open tools, and open technology Community and Geographic Outreach Education & Earth, Energy & Health & Scholarly Core Computer Environment Wellbeing Science Communication Advanced Research Tools and Services Judith Bishop was in the first group to study computer science in South Africa in 1970 and has stayed at the front of her field of programming languages for distributed systems ever since. She wrote the first BASIC compiler for ICL computers in 1972 and was involved in the first Pascal compiler for the in 1976. -

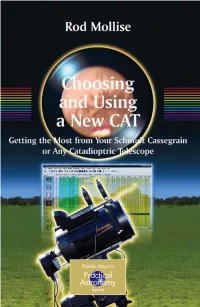

Getting the Most from Your Schmidt Cassegrain Or Any Catadioptric Telescope

Patrick Moore’s Practical Astronomy Series For other titles published in the series, go to www.springer.com/series/3192 Choosing and Using a New CAT Getting the Most from Your Schmidt Cassegrain or Any Catadioptric Telescope Rod Mollise Rod Mollise 1207 Selma Street Mobile AL 36604 USA ISBN 978-0-387-09771-8 e-ISBN 978-0-387-09772-5 DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-09772-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008934774 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by simi- lar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper springer.com About the Author Rod Mollise is an engineer by profession. He is also the author of numerous books and magazine articles on every aspect of amateur astronomy. Known to his fans as “Uncle” Rod Mollise, he is most well known for his books about catadioptric tel- escopes (CATs), which aim to help new CAT owners get past the inexperience and anxiety that often accompanies their entry into this wonderful hobby. -

Worldwide Telescope

WorldWide Telescope 1 WorldWide Telescope Editors Chenzhou Cui (崔辰州) , National Astronomical Observatory of China Ni Jing (景霓), Microsoft Research Asia Cuilan Qiao (乔翠兰) , Huazhong Normal University Rui Qi (齐锐), Beijing Planetarium Haoyi Wan (万昊宜) , Beijing Planetarium Yan Xu (徐艳), Microsoft Research 2 WorldWide Telescope Table of Content Introduction· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 4 Milestones· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 5 Acknowledge · · · · ·· · · · · · · · 42 3 WorldWide Telescope Introduction Interdisciplinary collaboration may be a popular trend but never a low hanging fruit. The success of Microsoft Research WorldWide Telescope (WWT) in China, however, is fortunately the right thing happens at the right time. Over the last three years, WWT has attracted numerous thought leader in astronomy, computer science and engineering, science education, and public outreach. The WWT user community in China has been growing exponentially. Every event we have gone through – the evolution of Virtual Observatory (VO) in the last decade; the involvement of Dr. Jim Gray, a computer scientist at Microsoft, in Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) development; the groundbreaking connection between the National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC) and Microsoft Research (MSR); the first public release of WWT on May 12, 2008; the message from Microsoft Research Asia (MSRA) on engaging Microsoft eScience research with Chinese Academy of Sciences; the award winning demo of the Chinese Valentine Story in WWT at MSRA Faculty Summit 2008; the highly received IYOA2009 Total Solar Eclipse online broadcast by NAOC; the great success of the “Microsoft Cup” WWT Tours Competition 2010 – tells the same successful story: opportunities only come to those who are ready and prepared. This brochure reviews the milestones of WWT being adopted by the Astronomy research and science education communities in China in 2008 – 2010.