Libertarianism: Bogus Anarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

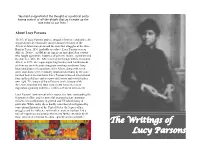

The Writings of Lucy Parsons

“My mind is appalled at the thought of a political party having control of all the details that go to make up the sum total of our lives.” About Lucy Parsons The life of Lucy Parsons and the struggles for peace and justice she engaged provide remarkable insight about the history of the American labor movement and the anarchist struggles of the time. Born in Texas, 1853, probably as a slave, Lucy Parsons was an African-, Native- and Mexican-American anarchist labor activist who fought against the injustices of poverty, racism, capitalism and the state her entire life. After moving to Chicago with her husband, Albert, in 1873, she began organizing workers and led thousands of them out on strike protesting poor working conditions, long hours and abuses of capitalism. After Albert, along with seven other anarchists, were eventually imprisoned or hung by the state for their beliefs in anarchism, Lucy Parsons achieved international fame in their defense and as a powerful orator and activist in her own right. The impact of Lucy Parsons on the history of the American anarchist and labor movements has served as an inspiration spanning now three centuries of social movements. Lucy Parsons' commitment to her causes, her fame surrounding the Haymarket affair, and her powerful orations had an enormous influence in world history in general and US labor history in particular. While today she is hardly remembered and ignored by conventional histories of the United States, the legacy of her struggles and her influence within these movements have left a trail of inspiration and passion that merits further attention by all those interested in human freedom, equality and social justice. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Libertarianism Karl Widerquist, Georgetown University-Qatar

Georgetown University From the SelectedWorks of Karl Widerquist 2008 Libertarianism Karl Widerquist, Georgetown University-Qatar Available at: https://works.bepress.com/widerquist/8/ Libertarianism distinct ideologies using the same label. Yet, they have a few commonalities. [233] [V1b-Edit] [Karl Widerquist] [] [w6728] Libertarian socialism: Libertarian socialists The word “libertarian” in the sense of the believe that all authority (government or combination of the word “liberty” and the private, dictatorial or democratic) is suffix “-ian” literally means “of or about inherently dangerous and possibly tyrannical. freedom.” It is an antonym of “authoritarian,” Some endorse the motto: where there is and the simplest dictionary definition is one authority, there is no freedom. who advocates liberty (Simpson and Weiner Libertarian socialism is also known as 1989). But the name “libertarianism” has “anarchism,” “libertarian communism,” and been adopted by several very different “anarchist communism,” It has a variety of political movements. Property rights offshoots including “anarcho-syndicalism,” advocates have popularized the association of which stresses worker control of enterprises the term with their ideology in the United and was very influential in Latin American States and to a lesser extent in other English- and in Spain in the 1930s (Rocker 1989 speaking countries. But they only began [1938]; Woodcock 1962); “feminist using the term in 1955 (Russell 1955). Before anarchism,” which stresses person freedoms that, and in most of the rest of the world (Brown 1993); and “eco-anarchism” today, the term has been associated almost (Bookchin 1997), which stresses community exclusively with leftists groups advocating control of the local economy and gives egalitarian property rights or even the libertarian socialism connection with Green abolition of private property, such as and environmental movements. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Quong-Left-Libertarianism.Pdf

The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 19, Number 1, 2011, pp. 64–89 Symposium: Ownership and Self-ownership Left-Libertarianism: Rawlsian Not Luck Egalitarian Jonathan Quong Politics, University of Manchester HAT should a theory of justice look like? Any successful answer to this Wquestion must find a way of incorporating and reconciling two moral ideas. The first is a particular conception of individual freedom: because we are agents with plans and projects, we should be accorded a sphere of liberty to protect us from being used as mere means for others’ ends. The second moral idea is that of equality: we are moral equals and as such justice requires either that we receive equal shares of something—of whatever it is that should be used as the metric of distributive justice—or else requires that unequal distributions can be justified in a manner that is consistent with the moral equality of persons. These twin ideas—liberty and equality—are things which no sound conception of justice can properly ignore. Thus, like most political philosophers, I take it as given that the correct conception of justice will be some form of liberal egalitarianism. A deep and difficult challenge for all liberal egalitarians is to determine how the twin values of freedom and equality can be reconciled within a single theory of distributive justice. Of the many attempts to achieve this reconciliation, left-libertarianism is one of the most attractive and compelling. By combining the libertarian commitment to full (or nearly full) self-ownership with an egalitarian principle for the ownership of natural resources, left- libertarians offer an account of justice that appears firmly committed both to individual liberty, and to an egalitarian view of how opportunities or advantages must be distributed. -

Political Ideology Chapter 9: Political Ideology|183

CHAPTER 9: Political Ideology Chapter 9: Political Ideology|183 "Aconservativeisaman withtwoperfectlygood legswho,however,has neverlearnedhowto walkforward." FranklinDelano Roosevelt, 32ndPresidentofthe UnitedStates “Thetroublewithour liberalfriendsisnotthat theyareignorant,but thattheyknowsomuch thatisn'tso.” 9.0 | What’s in a Name? RonaldReagan, 40thPresidentofthe Have you ever been in a discussion, debate, or perhaps even a heated UnitedStates argument about government or politics where one person objected to another person’s claim by saying, “That’s not what I mean by conservative (or liberal)? If so, then join the club. People often have to stop in the middle of a good political discussion when it becomes clear that the participants do not agree on the meanings of the terms that are central to the discussion. This can be the case with ideology because people often use familiar terms such as conservative, liberal, or socialist without agreeing on their meanings. This chapter has three main goals. The first goal is to explain the role ideology plays in modern political systems. The second goal is to define the major American ideologies: conservatism, liberalism, and libertarianism. The primary focus is on modern conservatism and liberalism. The third goal is to explain their role in government and politics. Some attention is also paid to other “isms”—belief systems that have some of the attributes of an ideology—that are relevant to modern American politics such as environmentalism, feminism, terrorism, and fundamentalism. The chapter begins with an examination of ideologies in general. It then examines American conservatism, liberalism, and other belief systems relevant to modern American politics and government. 9.1 | What is an ideology? An ideology is a belief system that consists of a relatively coherent set of ideas, attitudes, or values about government and politics, AND the public policies that are designed to implement the values or achieve the goals. -

Haymarket Riot (Chicago: Alexander J

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS1 MONUMENT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Haymarket Martyrs' Monument Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 863 South Des Plaines Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Forest Park Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code: 031 Zip Code: 60130 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites ___ structures 1 ___ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_Q_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Designated a NATIONAL HISTrjPT LANDMARK on by the Secreury 01 j^ tai-M NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS' MONUMENT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National_P_ark Service___________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Anarchism and Libertarianism

CHAPTER 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism Roderick T. Long Introduction “Libertarianism,” understood as a term for a specific political ideology, origi- nated as a synonym for anarchism, and more precisely the communist anar- chism of Joseph Déjacque (1821–1864), whose use of “libertaire” in this sense dates to 18571—though individualist anarchists soon picked up the term as well.2 Nowadays, however, the term “libertarianism” is frequently associated, particularly in English-speaking countries, with a movement favoring free mar- kets, private property, and economic laissez-faire, generally resting either on the efficiency of the price system in coordinating individuals’ plans,3 or else on an ethical principle of self-ownership or non-aggression4 which is taken to define individuals’ rights against forcible interference with their persons and (justly acquired) property. This is the sense in which the term “libertarian” will be employed here. (Today French actually has two words corresponding to the English libertarian: “libertaire,” meaning an anarchist, particularly a left-wing anarchist, and “libertarien,” for the free-market advocate.) It is with the relation of libertarianism (in the free-market sense) to anarchism that this chapter is concerned. While sometimes considered a form of conservatism, libertarianism dif- fers from typical versions of conservatism in endorsing a broad range of social liberties, and thus opposing, e.g., drug laws, censorship laws, laws restricting consensual sexual activity, and the like. (Libertarians usually, though not al- ways, differ from typical conservatives in opposing military interventionism 1 Joseph Déjacque, De l’être-humain mâle et femelle: Lettre à P.J. Proudhon (New Orleans: Lamarre, 1857). -

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 147 the Haymarket Affair

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 147 The Haymarket Affair - Part I Lead: In early May 1886 in the Haymarket area of Chicago a bloody confrontation occurred between police and workers. There followed the first "Red Scare" in American social history. Intro.: "A Moment in Time" with Dan Roberts. Content: The so-called Haymarket Affair began on May 3 when Chicago police attacked a crowd of strikers at the McCormick Reaper Works, killing and wounding several men. The next night anarchists held a protest rally near Haymarket Square in the commercial area of the City. Just as the meeting was breaking up because of the approach of a storm a squad of police arrived and ordered the crowd to disperse. The speaker Samuel Fielden protested but was getting down from the wagon to comply when someone threw a bomb into the police ranks. The officers lost control of themselves and started firing in all directions killing, and wounding civilians and policemen as well. Chicago that spring was in the grip of wide-scale labor protest focusing on demands for an eight-hour work day. These protests were being organized by labor associations from across the political spectrum. Some of the most effective work was done by the anarchists, a group of libertarian socialists who, in part, took their philosophical inspiration from Mikail Bakunin who opposed Karl Marx’s insistence on a centralized and disciplined Communist party. They wanted a society based on voluntary cooperation of free individuals with no government and private property. Within their ranks, however, there were many who spoke the rhetoric of violence and more than a few were quite willing to use it.