Localising the Humanitarian Toolkit: Lessons from Recent Philippines Disasters August 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

American Meteorological Society 2011 Student Conference Paper

Sea Surface Height and Intensity Change in Western North Pacific Typhoons Julianna K. Kurpis, Marino A. Kokolis, and Grace Terdoslavich: Bard High School Early College, Long Island City, New York Jeremy N. Thomas and Natalia N. Solorzano: Digipen Institute of Technology& Northwest Research Associates, Redmond, Washington Abstract Eastern/Central Pacific Hurricane Felicia (2009) Western North Pacific Typhoon Durian (2006) Although the structure of tropical cyclones (TCs) is well known, there are innumerable factors that contribute to their formation and development. The question that we choose to assess is at the very foundation of what conditions are needed for TC genesis and intensification: How does ocean heat content contribute to TC intensity change? Today, it is generally accepted that warm water promotes TC development. Indeed, TCs can be modeled as heat engines that gain energy from the warm water and, in turn, make the sea surface temperature (SST) cooler. Our study tests the relationship between the heat content of the ocean and the intensification process of strong Western North Pacific (WNP) Typhoons (sustained winds greater than 130 knots). We obtained storm track and wind speed data from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center and sea surface height (SSH) data from AVISO as a merged product from altimeters on three satellites: Jason-1, November/December: 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 Aug: 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jason-2, and Envisat. We used MATLAB to compare the SSH to the wind speeds, The strongest wind for Typhoon Durian occurred when the SSH was below using these as proxies for ocean heat content and intensity, respectively. -

Supporting Shine (School Hydrological Information Network) Increasing Children’S Awareness and Participation in Disaster Risk Reduction

Project ENCORE Enhancing Community Resilience to Disasters Supporting SHINe (School Hydrological Information Network) Increasing children’s awareness and participation in disaster risk reduction On September 26, 2011, Typhoon Nesat (Pedring) hit close to 3,500 communities in the northern region of the Philippines. Typhoon Nalgae (Quiel) hit on October 1, taking the same route. About 4 million were affected by the typhoons, destroying agricultural lands, road and water systems, health centers and 914 schools. A total of 101 people died, including 42 children. Save the Children’s Project ENCORE (Enhancing Community Resilience to Disasters) builds on the Nesat/Nalgae emergency as well as other programs’ experience to increase the understanding of the hazards the province of Bulacan faces. Through an innovative urban disaster risk reduction approach, the project aims to facilitate the organizing of child-led groups to disseminate DRR/mitigation messages and implement DRR/mitigation activities supporting the province's SHINe (School Project ENCORE aims to: Hydrological Information Network) program. Increase the capacity of children In coordination with Ms. Liz Mungcal, Bulacan’s Provincial and youth to identify risks, Disaster Risk Reduction Management Officer, Mr. Hilton solutions, and initiate action on Hernando, Assistant Weather Services Chief of the Pampanga River Basin Flood Forecasting and Warning DRR within their communities; Center/PAGASA which is under the Department of Science and Technology, and the Department of Education Improve the capacity of Division of Bulacan, SHINe orientation sessions were households to adopt appropriate conducted for nine (9) schools covered by ENCORE. waste management and The high school batch was conducted on February 8 at Sta. -

Check List Act Appeals Format

SECRETARIAT 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland TEL: +41 22 791 6033 FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www.actalliance.org Preliminary Appeal Philippines Assistance to Typhoon-affected - PHL111 Appeal Target: US$ 432,313 Geneva, 7 October 2011 Dear colleagues, While recovering from the devastation caused by super Typhoon Mina in August this year, communities and families in many provinces in Luzon were again hit by back to back super typhoons Nesat and Typhoon Nalgae, which wrecked havoc in most parts of Luzon. Nesat affected thousands of families in the 17 cities and municipalities in Metro Manila, especially those living in low-lying and flood-prone areas. The situation was worsened with the Typhoon Nalgae which brought-in heavy rains and badly affected provinces in Northern and Central Luzon. The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) reported that a total of 1,183,530 families or 5,534,410 persons have been affected in 3,252 villages in 349 municipalities, 41 cities in the 34 provinces of Regions I, II, III, IV-A, IV-B, and V, CAR, NCR and Region VI. The number of Typhoon Nesat affected population alone practically comprised three-fourths of the average number of disaster-affected population in a given year, which is at 7 million. The NDRRMC also reported that the national death toll from Typhoons Nesat and Nalgae climbed to 55 individuals with 63 others injured and 30 more others still missing. Destruction of property was placed at 7,540 totally damaged houses and 41,224 partially damaged houses. -

A Domestication Strategy of Indigenous Premium Timber Species by Smallholders in Central Visayas and Northern Mindanao, the Philippines

A DOMESTICATION STRATEGY OF INDIGENOUS PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES BY SMALLHOLDERS IN CENTRAL VISAYAS AND NORTHERN MINDANAO, THE PHILIPPINES Autor: Iria Soto Embodas Supervisors: Hugo de Boer and Manuel Bertomeu Garcia Department: Systematic Botany, Uppsala University Examyear: 2007 Study points: 20 p Table of contents PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. CONTEXT OF THE STUDY AND RATIONALE 3 3. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 18 4. ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY 19 5. METHODOLOGY 20 6. RESULTS 28 7. DISCUSSION: CURRENT CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR DOMESTICATING PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES 75 8. TOWARDS REFORESTATION WITH PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: A PROPOSAL FOR A TREE 81 DOMESTICATION STRATEGY 9. REFERENCES 91 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of the preservation of the tropical rainforest is discussed all over the world (e.g. 1972 Stockholm Conference, 1975 Helsinki Conference, 1992 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, and the 2002 Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development). Tropical rainforest has been recognized as one of the main elements for maintaining climatic conditions, for the prevention of impoverishment of human societies and for the maintenance of biodiversity, since they support an immense richness of life (Withmore, 1990). In addition sustainable management of the environment and elimination of absolute poverty are included as the 21 st Century most important challenges embedded in the Millennium Development Goals. The forest of Southeast Asia constitutes, after the South American, the second most extensive rainforest formation in the world. The archipelago of tropical Southeast Asia is one of the world's great reserves of biodiversity and endemism. This holds true for The Philippines in particular: it is one of the most important “biodiversity hotspots” .1. -

ANNUAL REPORT BUILDING RESILIENCE • EMPOWERING COMMUNITIES Cover Rationale

2016 ANNUAL REPORT BUILDING RESILIENCE • EMPOWERING COMMUNITIES Cover Rationale This year our theme is ‘Resilience’ to give tribute to the various ways in which humans survive and strive through adverse time, such as natural disasters or conict. Surviving and striving through such events however requires a helping hand, that is where MERCY Malaysia plays a signicant role. Through various projects we aim to transfer expert knowledge, skills, provide necessary materials and equipment to enhance communities resilience against the disasters they face. One such project in 2016, which is depicted on the cover, took place in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Sierra Leone was crippled for several months by the Ebola virus, rapidly spreading amongst communities and killing thousands. Although communities showed great strength and courage in ghting the virus, the high level of poverty and lack of sanitation facilities in rural communities made some eorts eeting. Thereby, MERCY Malaysia decided to provide communities with assistance through the activities of building wells, delivering hygiene kits and educating students from 100 schools about hygiene and health, with the objective of increasing the communities’ resilience through the transfer of knowledge and provision of essential sanitation items. It is within our duty to assist communities where they need assistance and ensure communities are prepared for future disasters, all contributing towards making communities resilient. 69 118 100 73 83 CONTENTS Our Approach: Total Disaster Risk Management (TDRM) -

VIETNAM: TYPHOONS 23 January 2007 the Federation’S Mission Is to Improve the Lives of Vulnerable People by Mobilizing the Power of Humanity

Appeal No. MDRVN001 VIETNAM: TYPHOONS 23 January 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in 185 countries. In Brief Operations Update no. 03; Period covered: 10 December - 18 January 2007; Revised Appeal target: CHF 4.2 million (USD 3.4 million or EUR 2.6 million) Appeal coverage: 26%; outstanding needs: CHF 3.1 million (Click here for the attached Contributions List)(click here for the live update) Appeal history: • Preliminary emergency appeal for Typhoon Xangsane launched on 5 Oct 2006 to seek CHF 998,110 (USD 801,177 OR EUR 629,490) for 61,000 beneficiaries for 12 months. • The appeal was revised on 13 October 2006 to CHF 1.67 million (USD 1.4 million or EUR 1.1 million) for 60,400 beneficiaries to reflect operational realities. • The appeal was relaunched as Viet Nam Typhoons Emergency Appeal (MDRVN001) on 7 December 2006 to incorporate Typhoon Durian. It requests CHF 4.2 million (USD 3.4 million or EUR 2.6 million) in cash, kind, or services to assist 98,000 beneficiaries for 12 months. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) allocated: for Xangsane and Durian at CHF 100,000 each. Operational Summary: The Viet Nam Red Cross (VNRC), through its headquarters and its chapters, are committed towards supporting communities affected by a series of typhoons (Xangsane and Durian). The needs are extensive, with 20 cities and provinces stretching from the central regions to southern parts of the country hit hard with losses to lives, property and livelihoods. -

Typhoon Haiyan Action Plan November 2013

Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan Action Plan November 2013 Prepared by the Humanitarian Country Team 100% 92 million total population of the Philippines (as of 2010) 54% 50 million total population of the nine regions hit by Typhoon Haiyan 13% 11.3 million people affected in these nine regions OVERVIEW (as of 12 November) (12 November 2013 OCHA) SITUATION On the morning of 8 November, category 5 Typhoon Haiyan (locally known as Yolanda ) made a direct hit on the Philippines, a densely populated country of 92 million people, devastating areas in 36 provinces. Haiyan is possibly the most powerful storm ever recorded . The typhoon first ma de landfall at 673,000 Guiuan, Eastern Samar province, with wind speeds of 235 km/h and gusts of 275 km/h. Rain fell at rates of up to 30 mm per hour and massive storm displaced people surges up to six metres high hit Leyte and Samar islands. Many cities and (as of 12 November) towns experienced widespread destruction , with as much as 90 per cent of housing destroyed in some areas . Roads are blocked, and airports and seaports impaired; heavy ships have been thrown inland. Water supply and power are cut; much of the food stocks and other goods are d estroyed; many health facilities not functioning and medical supplies quickly being exhausted. Affected area: Regions VIII (Eastern Visayas), VI (Western Visayas) and Total funding requirements VII (Central Visayas) are hardest hit, according to current information. Regions IV-A (CALABARZON), IV-B ( MIMAROPA ), V (Bicol), X $301 million (Northern Mindanao), XI (Davao) and XIII (Caraga) were also affected. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2011

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2011 WMO-No. 1085 WMO-No. 1085 © World Meteorological Organization, 2012 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11085-5 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; the Climatic Research Unit (CRU), University of East Anglia, United Kingdom; the Climate Prediction Center (CPC), the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS), the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States of America; the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), United States; the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), United States; the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), United Kingdom; the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC), Germany; and the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, United States. -

Our Core Values

URÀW RUJDQLVDWLRQ IRFXVLQJ RQ QDEOH KHDOWKUHODWHG GHYHORSPHQW YXOQHUDEOH FRPPXQLWLHV LQ ERWK OUR CORE VALUES • We focus on rapid medical response for the assistance of communities affected by disasters • :HKROGRXUVHOYHVDFFRXQWDEOHWRRXUGRQRUVDQGEHQHÀFLDULHV • We recognise the value of working with partners and volunteers • We provide an opportunity for individuals to serve with professionalism, upholding the Code of Conduct for International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief NEWNNEW LOGOOGOGOGOGO RATIONALERRAATTIOTOONNAALLEE MERCY Malaysia’s UHIUHVKHGORJRHPERGLHVHIÀFLHQF\DQGHIIHFWLYHQHVV DPLGVWKXPLOLW\7KHORJRSHUVRQLÀHVFRXUDJHDQGGHWHUPLQDWLRQDPPLGVWKXP 7KH ORJRSHHUVRQQLÀH FRXUDJHD GHWHUPPLQD LRQWWKURXJKLWVJKLWV clear-cut and minimalist design. The lower case alphabets denotesd humility DVDYDOXHZHHPEUDFHLQRXUDSSURDFKWRRXUZRUNZLWKEHQHÀFLDDV DYDOXHHZHHPE DFH QR U SSURDFKKWR RXU NZLWK EHQHÀFFLDULHULHVDQGHVD G SDUWQHUV\HWWKHEROGIRQWVLJQLÀHVRXUDELOLW\WRIDFHFKDOOSDUWQHUV \HW H OG IRQW VLJQLÀÀHV RX DEL LW\ WR HFKDOOHQHQJHVDQGWREHQJHV DQG WR H HIIHFWLYHLQRXUZRUN7KH5R\DO%OXHVLJQLÀHVFDOPLQWLPHVRIHIIHFWLY LQ ZRUN 7KHH5R\DO%%OXHV JQLÀH FD P WLPHVRIFFULVLV7KH%ULJKWL V %ULJKW RedRed showsshows ourr commitmentcommmitment andan passionsion in workingwworkking withw h disasterdisaster affectedfected DQGLPSRYHULVKHGFRPPXQLWLHV7KHÁRZHURQWKHORJRLVWKHҊ%XQDQGLPPSRYHULVKHG RPP QL H 7KHÁRZZHU RQW RJRLV WKH%XQJDJD5D\Dҋ5D\ KLELVFXV K ELVFXV VLQHQVLV VVLQHQVL ZKLFKZKLFKK LV WKH QDWLRQDOQDW R DO ÁRZHUÁRZHU RI 0DOD\VLD7K0DOD\\VLD 7KLV -

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

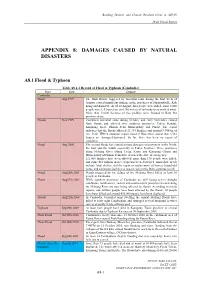

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Tropical Storm Tembin

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Philippines: Tropical Storm Tembin DREF n° MDRPH026 Glide n° TC-2017-000180-PHL; TC-2017-000182-PHL Date of issue: 22 December 2017 Categorization of crisis1: Yellow Operations manager: Point of contact: Patrick Elliott Atty. Oscar Palabyab Operations Manager Secretary General IFRC Philippine Country Office Philippine Red Cross Operation start date: 22 December 2017 Operation timeframe: 1 month, 22 January 2018 Operation budget: CHF 31,764 DREF allocation: CHF 31,764 N° of people affected: To be determined after landfall N° of people to be assisted: 5,000 Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: PRC is working with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in this operation. There are 12 Partner National Societies with presence in the Philippines. PRC and IFRC are also coordinating with International Committee of the Red Cross on this operation. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Government ministries and agencies including the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the Philippine Armed Forces, the Philippine National Police Force and Local Government Units are providing assistance to affected households. PRC have a seat on the NDRRMC. A. SITUATION ANALYSIS Description of the disaster There have been two significant weather systems to enter the Philippines Area of Responsibility (PAR) since 12 December 2017. Tropical Storm Kai-tak: On 12 December 2017, a low-pressure area (LPA) within the PAR developed into a Tropical Depression which was named Kai-tak (locally Urduja). The tropical depression moved north northwest, and by 14 December was reclassified as a Tropical Storm.