Shakespeare and His Collaborators Over the Centuries Pavel Drábek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romeo & Juliet

IMPORTANT NOTICE: The unauthorised copying of the whole or any part of this publication is illegal Romeo & Juliet for Abbey Primary School, Nottingham SCRIPT Copyright © 2014 by Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd Page numbers in this document correspond with those in the Micromusicals | Romeo & Juliet resource book 6 MICROMUSICALS | Romeo & Juliet SCRIPT Stage directions are suggestions only. Owners of a valid performance licence for Micromusicals | Romeo & Juliet may photocopy this script. SCENE 1 A street in Verona, Italy. Backdrop of an archway in the town. The stage is empty, apart for the two NARRATORS, who stand one on each side of the stage. NARRATOR 1 Two families in Verona fair fight endlessly with swords and knives, and as our tale will shortly show two star-crossed lovers lose their lives. NARRATOR 2 The Montagues and Capulets can never find a path to peace till death and sorrow, pain and loss make parents see that war must cease. NARRATOR 1 The lovers in this tale of strife are Romeo and Juliet. They love – although their families cannot forgive, cannot forget. They exit the stage. 1 19 37 SONG 1 | MONTAGUES & CAPULETS (PAGe 18) The ensemble cast are split into houses of MONTAGUES and CAPULETS. MONTAGUES begin off-stage left, and CAPULETS off-stage right. Throughout the song one cast member from each family strides with purpose to a pre-determined point on the stage to meet their counterpart. They face up to one another and mime the process of antagonising their foe. By the end of the song the stage is full of MONTAGUE and CAPULET pairs confronting each other. -

Troilus and Cressida the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Troilus and Cressida The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Cameron McNary (left) and Tyler Layton in Troilus and Cressida, 1999. Contents TroilusInformation and on William Cressida Shakespeare Shakespeare: Words, Words, Words 4 Not of an Age, but for All Mankind 6 Elizabeth’s England 8 History Is Written by the Victors 10 Mr. Shakespeare, I Presume 11 A Nest of Singing Birds 12 Actors in Shakespeare’s Day 14 Audience: A Very Motley Crowd 16 Shakespeare Snapshots 18 Ghosts, Witches, and Shakespeare 20 What They Wore 22 Information on the Play Synopsis 23 Characters 24 Scholarly Articles on the Play An “Iliad” Play 26 Where Are the Heroes and Lovers? 28 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Shakespeare: Words, Words, Words By S. -

Background Notes

Background Notes William Shakespeare and Romeo and Juliet Shakespeare: A brief biography • Shakespeare was born on April 23, 1564 in Stratford-on-Avon, England to an upper/ middle class family. Shakespeare: A brief biography • He learned Latin and Greek history in his grammar school as a child. This would explain the Latin and Greek references in his works. • There is not evidence that Shakespeare continued his schooling after elementary school. Shakespeare: A Brief Biography In 1582 at the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway who was 26. She was pregnant before they were married. Shakespeare: A Brief Biography • After a few years of marriage, Shakespeare left Stratford-on-Avon and his family for London to pursue his career in acting and writing. Shakespeare: A Brief Biography • Shakespeare wrote and acted with The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. This was an acting troupe that would perform during Shakespeare’s time. Shakespeare: A Brief Biography • It is believed that Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616. • In his will, Shakespeare left his daughters the majority of his wealth and possessions. He left his wife his “second best bed”. Shakespeare: A Brief Biography • The inscription on his tomb states: "Good friend for Jesus sake forbeare, To dig the dust enclosed here. Blessed be the man that spares these stones, And cursed be he that moves my bones.” Shakespeare wrote this because in his time, old bodies were dug up and burned to make room for new burials. Shakespeare despised this treatment of bodies, so he wrote this. Romeo and Juliet and Elizabethan Theater • Shakespeare did not create the story of Romeo and Juliet. -

Still Star Crossed 1X01

STILL STAR-CROSSED "A Bloody Summer" Written by Heather Mitchell Revised Studio Draft / Network Draft 1/18/16 ©2016, ABC Studios. All rights reserved. This material is the exclusive property of ABC Studios and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. Distribution to unauthorized persons or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the written consent of ABC Studios is strictly prohibited. Revised Studio Draft/Network Draft "Still Star-Crossed: "A Bloody Summer" ACT ONE EXT. VERONA - NIGHT Where we find ourselves on a WARM SUMMER NIGHT in the Northern Italian city-state of VERONA. We can HEAR the MUSIC and LAUGHTER of some distant PARTY carrying softly through the air... And as we watch, a TEENAGE GIRL steps out onto a BALCONY and speaks the following INCREDIBLY FAMOUS WORDS: JULIET Oh Romeo, Romeo -- wherefore art thou Romeo? And just like that, we know WHERE we are, and WHEN we are, and WHO IT IS we're watching -- because this girl? On this night? Standing on this balcony? Is JULIET CAPULET, a vision of youth, and beauty, and innocence -- and the heroine of THE GREATEST LOVE STORY EVER TOLD. And as she continues... JULIET (CONT'D) Deny thy father, and refuse thy name... ...Her words are DROWNED OUT by the PRE-LAPPED SOUND of some extremely non-innocent PANTING and MOANING, which we follow as we DRIFT FROM THE BALCONY down into... EXT. GARDEN - NIGHT Where a MAN and a WOMAN are busy making the beast with two backs in some surprisingly comfortable bushes. The man, BENVOLIO MONTAGUE (20s; dark and dangerous) stops sharply when he HEARS a MALE VOICE reply to Juliet: MALE VOICE (O.S.) I take thee at thy word. -

Romeo and Juliet Textbook.Pdf

Before Reading Video link at The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet thinkcentral.com Drama by William Shakespeare VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML9-1034 Is LOVE stronger than HATE? It sounds like a story ripped from the tabloids. Two teenagers fall in RL 2 Determine a theme of a love at a party. Then they learn that their parents hate each other. text. RL 3 Analyze how complex The teenagers’ love is forbidden, so not surprisingly, they cling to characters develop over the course of a text, interact with each other even more tightly. Murder and suffering ensue, and by other characters, and advance the the end, a whole town is in mourning. What love can—and cannot— plot or develop the theme. RL 9 Analyze how an author overcome is at the heart of Romeo and Juliet, considered by many to draws on source material in a be the greatest love story of all time. specific work. RL 10 Read and comprehend dramas. L 3 Apply knowledge of language to understand how language DEBATE People say that love conquers all. Is this statement true, functions in different contexts or is it just a cliché? How powerful is love? Discuss this topic in a and to comprehend more fully when reading or listening. small group. Talk about instances in which love has brought people together as well as times when hate has driven them apart. Then form two teams and debate the age-old question, Is love stronger than hate? 1034 NA_L09PE-u10-brRome.indd 1034 1/14/11 8:34:36 AM Overview text analysis: shakespearean drama Act One You can probably guess that a tragedy isn’t going to end We meet the Montagues and the Capulets, with the words “and they all lived happily ever after.” two long-feuding families in the Italian city Shakespearean tragedies are dramas that end in disaster— of Verona. -

Romeo and Juliet Act 3 Page | 69 Act 3, Scene 1

Romeo and Juliet Act 3 Act 3, Scene 1 Enter MERCUTIO, BENVOLIO, Mercutio's PAGE, and others MERCUTIO, his page, and BENVOLIO enter with other men. BENVOLIO BENVOLIO Page | 69 I pray thee, good Mercutio, let's retire. I'm begging you, good Mercutio, let's call it a day. It's hot The day is hot; the Capulets, abroad; outside, and the Capulets are wandering around. If we bump And if we meet we shall not 'scape a brawl, into them, we'll certainly get into a fight. When it's hot outside, For now, these hot days, is the mad blood stirring. people become angry and hotblooded. MERCUTIO MERCUTIO 5 Thou art like one of those fellows that, when he enters the You're like one of those guys who walks into a bar, slams his confines of a tavern, claps me his sword upon the table and says sword on the table, and then says, “I pray I never have to use “God send me no need of thee!” and, by the operation of the you.” By the time he orders his second drink, he pulls his second cup, draws it on the drawer when indeed there is no need. sword on the bartender for no reason at all. BENVOLIO BENVOLIO Am I like such a fellow? Am I really like one of those guys? MERCUTIO MERCUTIO Come, come, thou art as hot a Jack in thy mood as any in Italy, Come on, you can be as angry as any guy in Italy when you're and as soon moved to be moody, and as soon moody to be in the mood. -

Peter Saccio

William Shakespeare: Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies Part I Professor Peter Saccio THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Peter Saccio, Ph.D. Leon D. Black Professor of Shakespearean Studies Dartmouth College Peter Saccio has taught at Dartmouth College since 1966. He chaired the English department from 1984 to 1988; in addition, he has won Dartmouth’s J. Kenneth Huntington Memorial Award for Outstanding Teaching. He has served as visiting professor at Wesleyan University and at University College in London. He received a B.A. from Yale University and a Ph.D. from Princeton. He is the author of The Court Comedies of John Lyly (1969) and Shakespeare's English Kings (1977), the latter a classic in its field. He edited Middleton’s comedy A Mad World, My Masters for the Oxford Complete Works of Thomas Middleton (1996). He has published or delivered at conferences more than twenty papers on Shakespeare and other dramatists. Professor Saccio has directed productions of Twelfth Night, Macbeth, and Cymbeline. He has devised and directed several programs of scenes from Shakespeare and from modern British drama, and he served as dramaturg for the productions of his Dartmouth colleagues. He has acted the Shakespearean roles of Casca, Angelo, Bassanio, and Henry IV as well as various parts in the ancient plays of Plautus and the modern plays of Harold Pinter, Tom Stoppard, and Peter Shaffer. ©1999 The Teaching Company Limited Partnership i Table of Contents William Shakespeare: Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies Part I Professor Biography ........................................................................................... i Foreword .......... ................................................................................................. 1 Lecture One Shakespeare Then and Now...................................... 3 Lecture Two The Nature of Shakespeare’s Plays.......................... -

Romeo and Juliet As a Tragedy of Fate and Character

---.----ROMEO AND JULIET AS A TRAGEDY OF FATE AND CHARACTER By JAGRITI V. DESAI I/ Bachelor of Arts N & A Arts College Vidyanagarv India 1963 ])!laster of Arts Sardar Patel University Vidyanagar, Gujarat, India 1965 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requ.irements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1968 (\1 __,,,! OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OCT 24 1960 ------ROMEO AND JULIET AS A TRAGEDY OF FATE AND CHARACTER Thesis Approved: . .S 11 j 1-AAJ,, _A.,....., Dean brtne"firaduile College ii PREFACE My young heart is always fascinated by the idea of the young love crushed between the giant wheels of love and hat= . ,...__ _ reda Romeo __and Juliet is a tragedy of young love. Shake- speare has written great tragedies. His tragedies present a study in contrast with great Greek tragedies, wherein fate is responsible for the tragic end of the protagonists .. Romeo ~ Juliet is a tragedy which is a fusion of Greek tragedy and" Shakespearean tragedy. My purpose is to show whether Romeo and Juliet is a tragedy of fate, or characterv or both .. In my thesis I have studied the setting, the characters of Romeo and Juliet, and the action in'Romeo ~ Juliete I hmre examined the prologue, the passages which. indicate that the tragedy is predestined. My thorough study of the char= acters of Romeo and Juliet shows that the tragedy is in part the consequence of various flaws in these characters themselves. In presenting a new outlook on the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet,. -

The Montagues and the Capulets • Act II Star-Crossed Lovers • Act III Mercutio and Tybalt • Act IV Fortune’S Fool • Act V with a Kiss, I Die

Contents About the novel page 2 • The author • The plot • The film The play page 3 • The characters • The cast and the costumes • The prompts The script page 5 • Act I The Montagues and the Capulets • Act II Star-Crossed Lovers • Act III Mercutio and Tybalt • Act IV Fortune’s Fool • Act V With a Kiss, I Die Activities page 14 1 Puoi scaricare dal sito www.elilaspigaedizioni.it tutti gli audio in formato MP3. Romeo and Juliet About the novel The author Name William Shakespeare Born 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon Family His father, John, made and sold gloves 1. He was an important person in Stratford. His mother’s name was Mary. John and Mary had eight children, but three of them died when they were young. Curiosity Facts At the age of 18, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway. She was 26. They had a daughter, Susanna, and twins, a boy, Hamnet and a girl, Judith. Hamnet died when he was eleven. By 1595, Shakespeare was famous in London as an actor for an important theatre group which built the Globe Theatre. He was also becoming a successful playwright. During his life he wrote 38 plays and many poems. He is often called England’s national poet. He died in 1616 at the age of 52 and was buried in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. The plot The play is a tragedy about the ‘star-crossed’ 2 young lovers, Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet. The themes running through the play include love and passion, hatred 3 and fate. -

Romeo and Juliet Characters English 9 Romeo

Romeo and Juliet Characters English 9 Romeo • Around 16 years old • Son of Lord and Lady Montague • Not at all interested in violence • Impulsive, immature in some ways • A devoted friend and passionate lover Juliet • 13 years old • Daughter of Lord and Lady Capulet • Trusting, naive, and sheltered • Courageous and intense Juliet’s Nurse • Has cared for Juliet all her life; is a friend and a confidant at this point • Long-winded and sometimes vulgar • Funny and practical Friar Lawrence • A Franciscan monk • Friend to both Romeo and Juliet • Ultimately wants peace between the families • Gives advice and tries to help Tybalt • A Capulet, Juliet’s cousin • Fashion-conscious and a bit vain • Quick to anger and hates the Montagues Mercutio • Romeo’s close friend • Relative of the prince • Imaginative and witty • Hates people who are pretentious or obsessed with the latest fashions • Can be a bit hot-headed Benvolio • Romeo’s cousin and friend • Thoughtful • Tries to help Romeo get his mind off of love • Tries to defuse violence Lord Capulet • Father of Juliet • Enemy (for unknown reasons) of the Montagues • Truly loves his daughter but does not really know her Lady Capulet • Mother of Juliet • Married young herself • Wants Juliet to marry Count Paris, a suitable match in her eyes • Relies on the Nurse to help her raise Juliet Count Paris • A kinsman of the prince • Suitor of Juliet, preferred by Juliet’ s parents • Assumes Juliet will marry him without really asking her or getting to know her Lord Montague • Romeo’s father • Bitter enemy of the Capulets • Worried about Romeo’s moping and melancholy at the beginning of the play Lady Montague • Romeo’s mother • Dies of grief near the end Prince Escalus • Prince of Verona • Kinsman of Mercutio and Paris • Wants public peace at all costs. -

William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet on Screen

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE – FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV ANGLOFONNÍCH LITERATUR A KULTUR William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet on Screen BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Vedoudcí bakalářské práce (supervisor): Zpracovala (author): PhDr. Soňa Nováková, CSc., M.A. Eva Rösslerová Studijní obor (subject): Praha, srpen 2016 Anglistika-amerikanistika 1 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, že jsem řádně citovala všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. I declare that the following BA thesis is my own work for which I used only the sources and literature mentioned, and that this thesis has not been used in the course of other university studies or in order to acquire the same or another type of diploma. V Praze dne 16. srpna 2016 ............................................... 2 Above all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to PhDr. Soňa Nováková, CSc., M.A. for her honest and inspiring feedback throughout my BA studies. I would also like to thank Zdeněk Polívka, Klára Vozábová and Alena Kopečná for their unfaltering words of encouragement. Souhlasím se zapůjčením bakalářské práce ke studijním účelům. I have no objections to the BA thesis being borrowed and used for study purposes 3 THESIS ABSTRACT The aim of the thesis is to explore the film adaptations of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and to compare their thematic shifts of the adapted text. Primary focus will be put on Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968), Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996), and Carlo Carlei’s Romeo & Juliet (2013). This choice does not entirely exclude other adaptations, as they will be alluded to whenever some of their features become relevant to the discussion at hand. -

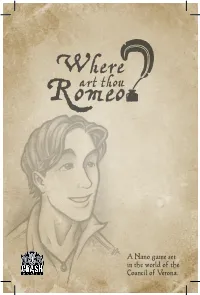

A Nano Game Set in the World of the Council of Verona. Players 3-5 Components: 5 Cards Time: 5-15 Minutes

A Nano game set in the world of the Council of Verona. Players 3-5 Components: 5 cards Time: 5-15 minutes Overview To start the game randomly chose a player to take on the role of Juliet and give that player the Juliet Card face-up. The Juliet role will rotate clockwise each round so that each player will take on the role of Juliet once. In a 3-Player game there will be three rounds, in a four-player game there will be four rounds, etc. Setup The card with a icon is only used in a 4 or 5 player game and the card with the icon is only used in a 5 player game. Shuffle the appropriate cards and randomly deal one of the remaining cards to each player face-down. It is important that these cards are kept secret. Game Play Juliet Each player, other than Juliet, not present. not examines their role card and is Romeo is present. is decides which of the two different Mercutio If is chosen. is roles they wish to play. Once the Romeo If player has decided on their role they place their card face down in such a way that their chosen role is closest to them and the non chosen role is closest to Juliet. This is a 3 player setup. Players 2 and 3 have not yet revealed their When she is ready the Juliet Player roles to player 1, Juliet. 2 will indicate that the 30 second lobby period has begun and players will now begin to tell Juliet whether or not they are Romeo (players may say whatever they wish during the lobby period but may not reveal their card) Players may chose to place their card face down at any point before or during the lobby period but once the role is placed down it may not be changed.