REFIGURING the PAST with THEATRE Mark Fleishman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerging Artists Bare Their Hearts Through Art

GET YOUR COPY with your MR DELIVERY order from FREE Thurs-Sat each week YOUR FREE GUIDE TO YOUR FREE TIME ÷ 18 February - 24 February 2016 ÷ Issue 611 Play exposes dark underbelly of politics – page 3 Clooney takes us back to 50s Hollywood – page 8 - Page 10 Emerging artists bare their hearts through art LaLiga is coming to Cape Town – page 11 Follow us online: @48hrsincapetown • www.facebook.com/next48hours • www.48hours.co.za The Next 48hOURS • Socials Seen at The Discovery Sport Industry Awards 2016 at Sandton Convention Centre - Pictures by Gallo Images Post Valentine’s Day thoughts Looking for interesting things has Am I fast-forwarding or rewind- ers (especially to younger folk) when How does one, for example, un- become part of me, like an append- ing? Actually neither. I am right they say: “Just be yourself.” How derstand “light” if one cannot open age: observing and listening to eve- where I need to be. A re-watching does one “be yourself” if you have oneself to understanding “dark- Encore rything and everyone absorbedly so of ‘Scent of a Woman’ refers. It is no idea who the hell you are? We are ness”? And, I have also always main- that I might find my topic(s) for the the scene where Al Pacino’s character too often so many different versions tained that you only get to know By Rafiek Mammon week to write about. defends Chris O’ Donnell’s character of ourselves. And when we are no your true self if you are prepared to [email protected] Sometimes I get close to deadline at a school hearing, and he speaks longer around someone remembers spend real quality time with said self day and I have very little to write (in pure Pacino style) about snitches some version of who they thought and bare your honest thoughts and about, but the minute I am at the and integrity and about his soul not you were…like a fading polaroid. -

Copy of Tracking 2018

2019 TRACKING OF 5 GRADUATE COHORTS OF MAGNET THEATRE'S FULLTIME TRAINING AND JOB CREATION PROGRAMME MAGNET THEATRE IS ONE OF SOUTH AFRICA’S BEST KNOWN INDEPENDENT PHYSICAL THEATRE COMPANIES THAT HAS BEEN OPERATING IN AND OUTSIDE OF SOUTH AFRICA FOR THE PAST 32 YEARS. MAGNET THEATRE RUNS THE ONLY SUITE OF BRIDGING PROGRAMMES IN THEATRE ARTS FOR UNEMPLOYED YOUTH IN THE WESTERN CAPE. 6 3 % of our graduates are actively employed in the 9 7 % of our graduates creative industry. A find regular employment in further 6% are employed the creative industry and fulltime in the broader broader economy, are self- economy bringing the employed or futhering their studies. employment rate of graduates to 6 9 % . Magnet has been instrumental in facillitating 5 6 % of the graduates access to the University of shared their skills, Cape Town for 3 2 first teaching school learners generation university and young adults in attendees. 17 have community centres, high graduated, 3 with post- schools, tertiary graduate qualifications; and institutions, and 11 are still studying. professional theatres. TEL: +27 21 448 3436 FAX: +27 86 667 3436 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.magnettheatre.co.za 26 3% graduates from the youth 3% 3 % 3 % S development programmes U e l n f e - e m have furthered their studies at m p p l o l o y other tertiary institutions such y e d e as Rhodes University, UNISA, d CPUT, Waterfront Theatre 28% Fulltime 28% students School and others. 66% Employed 1 8 graduates are currently involved in community drama groups. -

BAXTER THEATRE Brilliant Impersonations of the Every Monday @ 7Pm - 9Pm

The Next 48hOURS ≈ Entertainment Guide Jackman proves that there is life after ‘Isidingo’ By Peter Tromp world and trying to find a solution to that numbness that now seems to be al- icola Jackman has the kind most a default setting for most people.” of super alert eyes that are In the play, which takes place in a almost hypnotizing. They are land called MinXa, this sense of unease so bright that they give off the is expressed as the great numbing dis- illusionN that she hardly blinks. ease called the Num-shaQ. “As MAfrika What is more is that she likes to goes through the various stories in the maintain eye contact throughout an in- production, she’s also discovering herself terview and is super aware of her sur- and taking the audience on this journey roundings, almost unnervingly so, even along with her,” says Jackman. paying attention to the notes I was The actress deliberately created the scribbling, reading and comprehending production as a family show that would my handwriting upside down when I appeal to ages five and up, because, have trouble deciphering my hieroglyph- as she says, “I didn’t want to lose the ics at the best of times. chance to connect with the kids.” It was obvious to me during our brief Although Jackman is alone on stage time how much she values human con- during the show, great care has been nection and the extent to which she is lavished on the conceptual elements of attuned to her surroundings. ‘MAfrika-kie’, with smell even playing a These are among the qualities that Nicola Jackman factor in the overall design. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FORUM THEATRE AS THEATRE

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FORUM THEATRE AS THEATRE FOR DEVELOPMENT IN EAST AFRICA Emily Jane Warheit, Doctor of Philosophy, 2017 Dissertation directed by: Associate Professor Laurie Frederik, Theatre and Performance Sturdies Theatre for development (TfD) includes a variety of performance practices that aim to communicate or foster dialogue in a development context. Forum Theatre, developed by Brazilian Director Augusto Boal as part of his Theatre of the Oppressed movement has become one of the most widely used forms in TfD. This dissertation looks at the use of Forum Theatre specifically in public health-focused programs funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Uganda and Kenya. The appeal of Forum Theatre for addressing development issues stems from its participatory nature, particularly as it aligns with current trends towards community involvement in development. However, power imbalances inherent in foreign-funded projects, public health communication theories modeled after advertising, and the realities of life- and livelihood-threatening conditions on the ground all work against the liberatory potential of the form. The focus of Forum Theatre is on identifying and combatting oppression; in developing communities, what oppressions can theatre projects initiated from the top down by USAID actually address in practice? This study is a multi-sited exploration of the organizations and individuals involved in the funding, planning, and executing of two forum theatre projects promoting global public health goals. Through interviews of stakeholders and organization publications including training manuals and project reports, I examine how the organizations involved implement, evaluate, and justify the effectiveness of the use of theatre in their work. -

19Th ASSITEJ World Congress & International Theatre Festival for Children and Young People

PROGRAMME | CRADLE OF CREATIVITY T: 021 822 0070 / 1 / 2 | E: [email protected] | www.assitej2017.org.za Book at 19th ASSITEJ World Congress & International Theatre Festival for Children and Young People 16 - 27 MAY a C ic a 2017 fr p A e th Town Sou PROGRAMME | CRADLE OF CREATIVITY T: 021 822 0070 / 1 / 2 | E: [email protected] | www.assitej2017.org.za Book at A Mano Animal Farm El Patio Teatro Nobulali Productions A Mano (By Hand) is a tender and delicate Seven decades have passed since the first performance, a theatrical diamond that is publication of Orwell’s Animal Farm, yet a tribute to arts and artisans. It is the story the plight of Manor Farm and its animal of a very small but very special hero with denizens is ever relevant in contemporary a great desire to escape from his pottery South Africa. Dressed in what seems to be shop window and those who live there with the broken fatigues of guerrillas, the him. Told with beautifully crafted clay characters embrace both political identity characters and remarkable artistry, A Mano and farm-animal-hood, teetering between is a touching and life-affirming story about the two in terms of their articulated values love, small failures, a potter’s wheel and and increasing hypocrisy. Muriel the goat four hands at play. El Patio Teatro build, and Clover the sheep effectively act as the model, write, direct and play. Together, Spain narrators in the aftermath of the uprising. South Africa they create moving, reflective and The fiery energy that exists between the all beautifully original performances inspired women cast is palpable, and offers a fresh by stories from everyday life and by the Direction: Julián Sáenz-López, Izaskun Fernández| Design: Julián Sáenz-López , approach to critically examining patriarchal Direction: Neil Coppen | Performance: Mpume Mthombeni, Tshego Khutsoane, lives of objects around them. -

SOCIAL RESPONSIVENESS REPORT 2015-2016 Our Mission UCT Aspires to Become a Premier Academic Meeting Point Between South Africa, the Rest of Africa and the World

SOCIAL RESPONSIVENESS REPORT 2015-2016 Our mission UCT aspires to become a premier academic meeting point between South Africa, the rest of Africa and the world. Taking advantage of expanding global networks and our distinct vantage point in Africa, we are committed, through innovative research and scholarship, to grapple with the key issues of our natural and social worlds. We aim to produce graduates whose qualifications are internationally recognised and locally applicable, underpinned by values of engaged citizenship and social justice. UCT will promote diversity and transformation within our institution and beyond, including growing the next generation of academics. CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 PREFACE 4 INTRODUCTION 6 CRITICAL REFLECTIONS ON INSTITUTION-WIDE STRATEGIC INITIATIVES 8 Introduction 9 Schools Improvement Initiative 11 African Climate and Development Initiative 19 Safety and Violence Initiative (SaVI): a reflection 27 Poverty and Inequality Initiative 39 UCT Knowledge Co-op 47 Global Citizenship Initiative 50 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE CAPE HIGHER EDUCATION CONSORTIUM (CHEC) 53 Partnerships with the Western Cape Government (WCG) 54 City of Cape Town 57 Going Global Conference of the British Council 59 Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Colleges 59 REPORT ON INITIATIVES FUNDED THROUGH NRF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT GRANTS 61 FACULTY REPORTS 70 Introduction 71 Faculty of Science 75 Faculty of Health Sciences 87 Faculty of Law 148 Faculty of Commerce 158 Graduate School of Business 186 Engineering and the Built Environment 195 Humanities 208 CHED 230 2 UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN SOCIAL RESPONSIVENESS REPORT 2015-2016 FOREWORD The challenges that confront our country, Africa and the world enjoin universities to begin to think differently about how they bring to bear their resources to engage with these challenges. -

Cultural Affairs Awards

CULTURAL AFFAIRS AWARDS Previous Recipients/Winners of the Awards since 1999 Updated March 2018 Updated March 2018 Page 1 of 27 2017/18 Recipients / Winners Categories ARTS AND CULTURE Stellenbosch International Best Contribution to the Visual Chamber Music Festival Arts, including Public Arts Ivy Meyer Best Contribution to the Performing Arts: Dance Ameera Conrad (The Fall) Best Contribution to the Performing Arts: Drama West Coast Youth Orchestra Best Contribution to the Performing Arts: Music Peter Voges Best Contribution to the Literary Arts, including Poetry, Prose and Play-writing Hein Marais (Township Angels) Best Contribution to Crafts LANGUAGE Louis David Nel Best Project towards the Promotion of South African Sign Language or the Marginalised Indigenous Languages of the Western Cape HERITAGE March Turok (Observatory Civic Most Active Conservation Body Association) MUSEUMS Lwandle Migrant Labour Museum Best Museum Promoting Social Inclusion Education Museum Best Museum Project Hester Charlotte Lotz Museum Volunteer of the Year Education Museum Best Contribution to the Preservation of Local Heritage GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Mountain Passes South Africa Substantial Contribution to Geographical Names in the Western Cape LIBRARIES Oney Emmerentia Le Roux Best Volunteer in a Public Library Friends of Elsies River Library Best Friends of a Public Library Valhalla Park Public Library Best Book Club of a Public Library Ottery Public Library Best Collaborative Public Library Programme/Project ARCHIVES Jeannette Unite Archives Advocacy Dr Johan -

Moyo, Arifani. 'Indigeneity and Theatre in the New South Africa.'

Indigeneity and Theatre in the New South Africa Arifani James Moyo Royal Holloway, University of London PhD in Theatre Studies 2015 Declaration of Authorship I, Arifani James Moyo, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 30 June 2015 2 Acknowledgements The writing, research and all sponsorship for this PhD thesis were part of the international, multidisciplinary humanities research project, Indigeneity in the Contemporary World: Politics, Performance, Belonging (2009 – 2014), a project that Professor Helen Gilbert initiated and led with funding from the European Research Council. The project headquarters was the Centre for International Theatre and Performance Research (CITPR) at the Department of Drama and Theatre, Royal Holloway University of London. The project looked at ―how indigeneity is expressed and understood in our complex, globalising world‖, and the diverse ways in which indigeneity‘s ―cultural, political, ethical and aesthetic issues are negotiated‖ through ―performance as a vital mode of cultural representation and a dynamic social practice‖ (www.indigeneity.net). The core research team included anthropologists and arts scholars with experience in indigenous peoples‘ movements of the Americas, Australia and the Pacific Islands. The project widely networked, and also hosted numerous fellowships, with indigenous scholars, artists and activists from around the globe. My task was to explore the topic of ‗Indigeneity in the New South Africa‘. I thank Professor Gilbert for this extraordinary experience, and for supervising the PhD. I also thank Professor Matthew Cohen, Doctor Lynette Goddard and Professor David Wiles for their generous support of the supervision. -

A Portrait of Prostitution, Told in Six Intimate Parts

A portrait© eentweedee produksies of prostitution, 2011 www.een2dee.co.za told in six intimate parts. We will be using the term sex workers throughout for the sake of consistency but this should not be taken as an argument for the decriminalization of sex work just as the use of the word prostitute should not be taken as an argument for the criminalization of the same trade. ex is an integral part of every human’s life. Whether having it, not having it, wanting it, not wanting it, talking about it, learning about it, we all have a relationship, opinions and expectations around sex. Prostitution, providing sexual service for another person in return for payment, has Sbeen present in every culture in recorded history and continues to operate around the world today. What for most people is a personal practice, for a group of individuals is a trade. Since 1994 there has been an ongoing debate in South Africa about how best to protect the human rights of sex workers. At present the South African Law Reform Commission is reviewing four proposals ranging across the spectrum from full criminalization to full decriminalization. Whilst attending a research forum around these issues earlier last year it struck me that in a room full of erudite and informed experts on this subject, from a variety of disciplines – department of health, NGO’s, academics – there was not one sex worker amongst them. The sex work trade is clearly not going to be eradicated and those who are working in this industry are vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. -

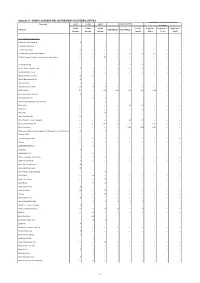

Ann 11 Grants Subs and Contr to Ext Orgs 1415.Xlsx

Annexure 11 - GRANTS, SUBSIDIES AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO EXTERNAL ENTITIES 2014/15 Medium Term Revenue & Expenditure Description 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 Current Year 2013/14 Framework Audited Audited Audited Full Year Budget Year Budget Year +1 Budget Year +2 R thousand Original Budget Adjusted Budget Outcome Outcome Outcome Forecast 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 Cash Transfers to Organisations 1st Bellville South Scout Group 10 – – – – – – – – 1st Bothasig Scout Group – – 5 – – – – – – 1st Ikwezi Scout Group 15 – – – – – – – – 2013 Maboneng Guguletu Arts Experience – – – – 50 50 150 – – 6th World Congress: Paediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery – – 750 – – – – – – 7570 Youth in Action – – – 7 7 7 – – – Abafazi iTemba - Women of Hope 10 – – – – – – – – Abangane Religious Group – 4 – – – – – – – Abaphumeleli Home of Safety 38 20 – – – – – – – Abatsha Environmental Group 96 – – – – – – – – Abba HIV Project 5 5 5 – – – – – – Abigail Women's Movement 72 18 23 – – – – – – ABSA Cape Epic 500 – 1 278 1 350 1 350 1 350 1 445 – – Actor's Voice Davedu-tainment 19 – – – – – – – – ACVV Bothasig Creche – 10 8 – – – – – – ACVV Old Age Home: ACVV Huis Jan Swart – – 15 – – – – – – Africa Centre – – – – 450 450 – – – Africa Tales – 3 – – – – – – – Africa Unite – – 37 – – – – – – African Centre for Cities 350 – – – – – – – – African Creative Economy Conference – – – – 600 600 – – – African Fashion International – – 1 200 – – – 1 300 – – African Travel Week – – – – 2 750 2 750 2 750 – – Afrikaanse Christelike Vroue Vereniging (ACVV De Grendel Creche ACVV Crèche, -

Cultural Affairs Awards

CULTURAL AFFAIRS AWARDS Previous Recipients/Winners of the Awards since 1999 Updated March 2019 Updated March 2019 Page 1 of 30 18th Ceremony March 2018 Recipients / Winners Categories AFTER SCHOOL Nompumelelo Rakabe After School Arts and PROGRAMME Culture Coaching Excellence ARTS, CULTURE AND Mzokuthula Gasa Contribution to Performing LITERATURE Arts: Dance Magnet Theatre Contribution to Performing Arts: Drama Music Exchange Contribution to Performing Arts: Music Athol Williams Contribution to the Literary Arts (including poetry, prose and play-writing) Jill Trappler Contribution to Visual, Audiovisual and Interactive Media (e.g. photography, film and video) Jacques La Grange Contribution to Design and Creative Spaces (fashion, graphic and landscape design) Jacobus Ryno Eksteen Best Project Contributing to support for People Living with Disability in the Visual, Performing and Literary Arts LANGUAGE Die Stigting vir Bemagtiging deur Neville Alexander Award for Afrikaans the Best Contribution towards the Promotion of Multilingualism Folio Inter Tel Best Project that Promoted South African Sign Language or the Marginalised Indigenous Languages of the Western Cape MUSEUMS !Khwa ttu Best Museum Project Updated March 2019 Page 2 of 30 Quaanitah Simons Museum Volunteer of the Year Joline Young Best Contribution to the Preservation of Local History HERITAGE 1001 South African Stories Most Innovative Heritage Conservation Project Stellenbosch Interest Group Most Active Conservation Body Shehnaz Cassim Moosa Most Active Volunteer or Heritage -

2011 Annual Review

SOUTH AFRICAN VISION The South African Holocaust & Genocide Foundation is dedicated to creating a more caring and just society in which human rights and diversity are respected and valued & FOUND ATION MISSION The South African Holocaust & Genocide Foundation • Serves as a memorial to the six million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust and all victims of Nazi Germany • Raises awareness of genocide with a particular focus on Rwanda • Teaches about the consequences of prejudice, racism, antisemitism and xenophobia, and the dangers of indifference, apathy and silence IN MEMORIAM We mourn the loss of the following Holocaust survivors who passed away in 2011 Barbara Spinner and Ida Wallach (Johannesburg) ANNUAL REVIEW Sara Jerusalmi (Cape Town) Dr Dora Love (South Africa and United Kingdom), who visited South Africa during the course of the year and spoke at all three Centres 2011 ii Foreword This review reflects exciting developments and the continued growth of the South African Holocaust & Genocide Foundation (SAHGF). Noteworthy are the relocation of the Durban Holocaust Centre to larger premises and the start of construction of the Johannesburg Holocaust & Genocide Centre with its world class permanent exhibition. These two Centres, together with the Cape Town Holocaust Centre, now in its 13th year, have engaged with a broad public in carrying out important education and remembrance work. Particularly gratifying is our growing regional and international reputation and our unique work in South Africa. SAHGF personnel participated in think tanks and conferences, locally and internationally, on the Holocaust and human rights, genocide prevention and museums’ roles in education and social change.