Infection of the Biomphalaria Glabrata Vector Snail by Schistosoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Original Article Influence of Food Type and Calcium

doi: 10.5216/rpt.v49i1.62089 ORIGINAL ARTICLE INFLUENCE OF FOOD TYPE AND CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATION ON GROWTH, OVIPOSITION AND SURVIVAL PARAMETERS OF Biomphalaria glabrata AND Biomphalaria straminea Wandklebson Silva da Paz1, Rosália Elen Santos Ramos1, Dharliton Soares Gomes1, Letícia Pereira Bezerra1, Laryssa Oliveira Silva2, Tatyane Martins Cirilo1, João Paulo Vieira Machado2 and Israel Gomes de Amorim Santos2 ABSTRACT Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by Schistosoma mansoni whose intermediate host is the snail of the genus Biomphalaria. This snail is geographically widespread, making the disease a serious public health problem. The purpose of this study was to analyze the growth, reproductive rates and mortality of B. glabrata and B. straminea in different calcium concentrations and food types. Freshly hatched snails stored in aquariums under different dietary and calcium supplementation programs were studied. Under these conditions, all planorbids survived, so there was no mortality rate and 79,839 eggs of B. straminea and 62,558 eggs of B. glabrata were obtained during the 2 months of oviposition. The following conditions: lettuce + fish food and lettuce + fish food + powdered milk resulted in the highest reproductive rates. In addition, supplementation with calcium carbonate and calcium sulfide in three different concentrations did not significantly influenced the amount of eggs or ovigerous masses. Thus, this study shows that changes in diet are crucial for the survival/oviposition of these planorbids, being an important study tool for population control. Calcium is also a key factor in these conditions, but more work is necessary to better assess its effect on snail survival. KEY WORDS: Laboratory breeding; Biomphalaria glabrata; Biomphalaria straminea; food type; calcium concentration. -

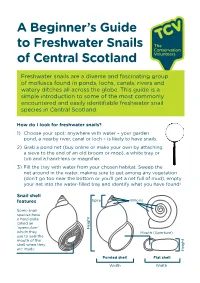

Freshwater Snail Guide

A Beginner’s Guide to Freshwater Snails of Central Scotland Freshwater snails are a diverse and fascinating group of molluscs found in ponds, lochs, canals, rivers and watery ditches all across the globe. This guide is a simple introduction to some of the most commonly encountered and easily identifiable freshwater snail species in Central Scotland. How do I look for freshwater snails? 1) Choose your spot: anywhere with water – your garden pond, a nearby river, canal or loch – is likely to have snails. 2) Grab a pond net (buy online or make your own by attaching a sieve to the end of an old broom or mop), a white tray or tub and a hand-lens or magnifier. 3) Fill the tray with water from your chosen habitat. Sweep the net around in the water, making sure to get among any vegetation (don’t go too near the bottom or you’ll get a net full of mud), empty your net into the water-filled tray and identify what you have found! Snail shell features Spire Whorls Some snail species have a hard plate called an ‘operculum’ Height which they Mouth (Aperture) use to seal the mouth of the shell when they are inside Height Pointed shell Flat shell Width Width Pond Snails (Lymnaeidae) Variable in size. Mouth always on right-hand side, shells usually long and pointed. Great Pond Snail Common Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis Radix balthica Largest pond snail. Common in ponds Fairly rounded and ’fat’. Common in weedy lakes, canals and sometimes slow river still waters. pools. -

Pomacea Canaliculata) Behaviors in Different Water Temperature Gradients

water Article Comparison of Invasive Apple Snail (Pomacea canaliculata) Behaviors in Different Water Temperature Gradients Mi-Jung Bae 1, Eui-Jin Kim 1 and Young-Seuk Park 2,* 1 Nakdonggang National Institute of Biological Resources, Sangju 37242, Korea; [email protected] (M.-J.B.); [email protected] (E.-J.K.) 2 Department of Biology, Kyung Hee University, Dongdaemun, Seoul 02447, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-961-0946 Abstract: Pomacea canaliculata (known as invasive apple snail) is a freshwater snail native to South America that was introduced into many countries (including Asia and North America) as a food source or for organic farming systems. However, it has invaded freshwater ecosystems and become a serious agricultural pest in paddy fields. Water temperature is an important factor determining behavior and successful establishment in new areas. We examined the behavioral responses of P. canaliculata with water temperature changes from 25 ◦C to 30 ◦C, 20 ◦C, and 15 ◦C by quantifying changes in nine behaviors. At the acclimated temperature (25 ◦C), the mobility of P. canaliculata was low during the day, but high at night. Clinging behavior increased as the water temperature decreased from 25 ◦C to 20 ◦C or 15 ◦C. Conversely, ventilation and food consumption increased when the water temperature increased from 25 ◦C to 30 ◦C. A self-organizing map (an unsupervised artificial neural network) was used to classify the behavioral patterns into seven clusters at different water temperatures. These results suggest that the activity levels or certain behaviors of P. canaliculata vary with the water temperature conditions. -

Gastropoda: Physidae) in Singapore

BioInvasions Records (2015) Volume 4, Issue 3: 189–194 Open Access doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/bir.2015.4.3.06 © 2015 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2015 REABIC Research Article Clarifying the identity of the long-established, globally-invasive Physa acuta Draparnaud, 1805 (Gastropoda: Physidae) in Singapore Ting Hui Ng1,2*, Siong Kiat Tan3 and Darren C.J. Yeo1,2 1Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Republic of Singapore 2NUS Environmental Research Institute, National University of Singapore, 5A Engineering Drive 1, #02-01, Singapore 117411, Republic of Singapore 3Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore, 2 Conservatory Drive, Singapore 117377, Republic of Singapore E-mail: [email protected] (THN), [email protected] (SKT), [email protected] (DCJY) *Corresponding author Received: 24 December 2014 / Accepted: 6 May 2015 / Published online: 2 June 2015 Handling editor: Vadim Panov Abstract The freshwater snail identified as Physastra sumatrana has been recorded in Singapore since the late 1980’s. It is distributed throughout the island and commonly associated with ornamental aquatic plants. Although the species has previously been considered by some to be native to Singapore, its origin is currently categorised as unknown. Morphological comparisons of freshly collected specimens and material in museum collections with type material, together with DNA barcoding, show that both Physastra sumatrana, and a recent gastropod record of Stenophysa spathidophallus, in Singapore are actually the same species—the globally-invasive Physa acuta. An unidentified physid snail was also collected from the Singapore aquarium trade. -

Abstract Volume

ABSTRACT VOLUME August 11-16, 2019 1 2 Table of Contents Pages Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………...1 Abstracts Symposia and Contributed talks……………………….……………………………………………3-225 Poster Presentations…………………………………………………………………………………226-291 3 Venom Evolution of West African Cone Snails (Gastropoda: Conidae) Samuel Abalde*1, Manuel J. Tenorio2, Carlos M. L. Afonso3, and Rafael Zardoya1 1Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN-CSIC), Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biologia Evolutiva 2Universidad de Cadiz, Departamento CMIM y Química Inorgánica – Instituto de Biomoléculas (INBIO) 3Universidade do Algarve, Centre of Marine Sciences (CCMAR) Cone snails form one of the most diverse families of marine animals, including more than 900 species classified into almost ninety different (sub)genera. Conids are well known for being active predators on worms, fishes, and even other snails. Cones are venomous gastropods, meaning that they use a sophisticated cocktail of hundreds of toxins, named conotoxins, to subdue their prey. Although this venom has been studied for decades, most of the effort has been focused on Indo-Pacific species. Thus far, Atlantic species have received little attention despite recent radiations have led to a hotspot of diversity in West Africa, with high levels of endemic species. In fact, the Atlantic Chelyconus ermineus is thought to represent an adaptation to piscivory independent from the Indo-Pacific species and is, therefore, key to understanding the basis of this diet specialization. We studied the transcriptomes of the venom gland of three individuals of C. ermineus. The venom repertoire of this species included more than 300 conotoxin precursors, which could be ascribed to 33 known and 22 new (unassigned) protein superfamilies, respectively. Most abundant superfamilies were T, W, O1, M, O2, and Z, accounting for 57% of all detected diversity. -

Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Molluscs

Cell and Tissue Research (2019) 377:475–503 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03085-9 REVIEW Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs Alexandre Lobo-da-Cunha1,2 Received: 21 February 2019 /Accepted: 26 July 2019 /Published online: 2 September 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The phylum Mollusca is one of the largest and more diversified among metazoan phyla, comprising many thousand species living in ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Mollusc-feeding biology is highly diverse, including omnivorous grazers, herbivores, carnivorous scavengers and predators, and even some parasitic species. Consequently, their digestive system presents many adaptive variations. The digestive tract starting in the mouth consists of the buccal cavity, oesophagus, stomach and intestine ending in the anus. Several types of glands are associated, namely, oral and salivary glands, oesophageal glands, digestive gland and, in some cases, anal glands. The digestive gland is the largest and more important for digestion and nutrient absorption. The digestive system of each of the eight extant molluscan classes is reviewed, highlighting the most recent data available on histological, ultrastructural and functional aspects of tissues and cells involved in nutrient absorption, intracellular and extracellular digestion, with emphasis on glandular tissues. Keywords Digestive tract . Digestive gland . Salivary glands . Mollusca . Ultrastructure Introduction and visceral mass. The visceral mass is dorsally covered by the mantle tissues that frequently extend outwards to create a The phylum Mollusca is considered the second largest among flap around the body forming a space in between known as metazoans, surpassed only by the arthropods in a number of pallial or mantle cavity. -

Mollusca: Gastropoda) from Islands Off the Kimberley Coast, Western Australia Frank Köhler1, Vince Kessner2 and Corey Whisson3

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 27 021–039 (2012) New records of non-marine, non-camaenid gastropods (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from islands off the Kimberley coast, Western Australia Frank Köhler1, Vince Kessner2 and Corey Whisson3 1 Department of Environment and Conservation of Western Australia, Science Division, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, Western Australia 6946; and Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia. Email: [email protected] 2 162 Haynes Road, Adelaide River, Northern Terrritory 0846, Australia. Email: [email protected] 3 Department of Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum, 49 Kew Street, Welshpool, Western Australia 6106, Australia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The coast of the Western Australian Kimberley boasts an archipelago that comprises several hundred large islands and thousands much smaller. While the non–marine gastropod fauna of the Kimberley mainland has been surveyed to some extent, the fauna of these islands had never been comprehensively surveyed and only anecdotal and unsystematic data on species occurrences have been available. During the Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation’s Kimberley Island Survey, 2008–2010, 22 of the largest islands were surveyed. Altogether, 17 species of terrestrial non–camaenid snails were found on these islands. This corresponds to about 75% of all terrestrial, non–camaenid gastropods known from the entire Kimberley region. In addition, four species of pulmonate freshwater snails were found to occur on one or more of four of these islands. Individual islands harbour up to 15, with an average of eight, species each. Species diversity was found to be higher in the wetter parts of the region. -

Differences in the Number of Hemocytes in the Snail Host Biomphalaria Tenagophila, Resistant and Susceptible to Schistosoma Mansoni Infection

Differences in the number of hemocytes in the snail host Biomphalaria tenagophila, resistant and susceptible to Schistosoma mansoni infection A.L.D. Oliveira1,4,5, P.M. Levada2, E.M. Zanotti-Magalhaes3, L.A. Magalhães3 and J.T. Ribeiro-Paes2 1Programa de Pós-Graduação Interunidades em Biotecnologia, USP, IPT, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Assis, SP, Brasil 3Departamento de Parasitologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brasil 4Departamento de Saúde, ADR, Biomavale, Assis, SP, Brasil 5Departamento de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Paulista, Assis, SP, Brasil Corresponding author: J.T. Ribeiro-Paes E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 9 (4): 2436-2445 (2010) Received November 5, 2010 Accepted November 12, 2010 Published December 21, 2010 DOI 10.4238/vol9-4gmr1143 ABSTRACT. The relationships between schistosomiasis and its intermediate host, mollusks of the genus Biomphalaria, have been a concern for decades. It is known that the vector mollusk shows different susceptibility against parasite infection, whose occurrence depends on the interaction between the forms of trematode larvae and the host defense cells. These cells are called amebocytes or hemocytes and are responsible for the recognition of foreign bodies and for phagocytosis and cytotoxic reactions. The defense cells mediate the modulation of the resistant and susceptible phenotypes of the mollusk. Two main types of hemocytes are found in the Biomphalaria hemolymph: the granulocytes and the hyalinocytes. We studied the variation in the number (kinetics) of hemocytes for 24 h after exposing the parasite to genetically selected and non-selected strains of Genetics and Molecular Research 9 (4): 2436-2445 (2010) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br Differences in the number of hemocytes in B. -

The Golden Apple Snail: Pomacea Species Including Pomacea Canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae)

The Golden Apple Snail: Pomacea species including Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) DIAGNOSTIC STANDARD Prepared by Robert H. Cowie Center for Conservation Research and Training, University of Hawaii, 3050 Maile Way, Gilmore 408, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA Phone ++1 808 956 4909, fax ++1 808.956 2647, e-mail [email protected] 1. PREFATORY COMMENTS The term ‘apple snail’ refers to species of the freshwater snail family Ampullariidae primarily in the genera Pila, which is native to Asia and Africa, and Pomacea, which is native to the New World. They are so called because the shells of many species in these two genera are often large and round and sometimes greenish in colour. The term ‘golden apple snail’ is applied primarily in south-east Asia to species of Pomacea that have been introduced from South America; ‘golden’ either because of the colour of their shells, which is sometimes a bright orange-yellow, or because they were seen as an opportunity for major financial success when they were first introduced. ‘Golden apple snail’ does not refer to a single species. The most widely introduced species of Pomacea in south-east Asia appears to be Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822) but at least one other species has also been introduced and is generally confused with P. canaliculata. At this time, even mollusc experts are not able to distinguish the species readily or to provide reliable scientific names for them. This confusion results from the inadequate state of the systematics of the species in their native South America, caused by the great intra-specific morphological variation that exists throughout the wide distributions of the species. -

Mollusca: Pulmonata: Planorbidae)1

_??_1993 The Japan Mendel Society Cytologia 58: 145 -149 , 1993 Polyploid Chromosome Numbers in the Torquis Group of the Freshwater Snail Genus Gyraulus (Mollusca: Pulmonata: Planorbidae)1 John B. Burch2 and Younghun Jung3 2 Museum of Zoology and Department of Biology , College of Literature, Science and the Arts, and School of Natural Resources , University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U. S. A. 3 Department of Parasitology, College of Medicine , Inha University, 253 Yong Hyun-Dong, Nam-Gu, Inchon , 402-751, Korea Accepted December 28, 1992 The subclass Pulmonata is a very large group of land, freshwater and marine gastropods which use a lung rather than gills for respiration. All pulmonate snails are hermaphroditic, and many are known to be capable of propagation by self fertilization when the more normal biparental mating is prevented. In such a group, a large amount of polyploidy might be ex pected, but chromosome surveys have shown that such is not the case. Very few pulmonate snails have been found to be polyploid (Burch and Huber 1966). The first pulmonate snail in which polyploidy was detected was Gyraulus (Torquis) cir cumstriatus (Tryon 1866, Burch 1960a). The chromosome numbers have been determined for several other species belonging to other subgenera of Gyraulus (Table 1). In these, the only number found has been n=18, 2n=36, which is the basic chromosome number for the family Planorbidae to which they belong (Burch and Patterson 1978). The genus Gyraulus comprises a large group of very small species of freshwater snails belonging to the pulmonate family Planorbidae. Although the various species each have circumscribed and often limited distributions, the genus itself is worldwide in distribution, occurring abundantly and commonly in diverse aquatic habitats on all of the continents. -

Snail Folio for Pdfing

cop aS e e S s e i t A vi q ti uatic Ac Trailing the Snail By Barbara S. Hoffman Focus UGH! SLIME! and WHAT A BEAUTIFUL SHELL! With the aid of the Scope-on-a-Rope, the magical world of are common reactions to snails. In cartoons, snails are snail behavior and characteristics becomes easily acces- featured as SLUGgish of movement and lowly of intellect. sible to the most reluctant learner. Background Snails are mollusks, or soft-bodied nonsegmented species have lungs and must surface to breathe. Land invertebrates. All mollusks have a large muscle commonly snails, also lung breathers, have two sets of tentacles with called a foot that is used for locomotion. Tissue called a their eyes at the top of the rear pair. The eye tips on the mantle covers the internal organs, and in most mollusk tentacles can be retracted for protection. species the mantle secretes a calcium shell to cover the soft body. This shell protects the mollusk from predators and Sea snails and some freshwater snails have an operculum, helps to keep the body moist. Mollusk shells provide no or horny plate, on the back of the foot, which serves as a body support. Slugs are frequently described as snails closure to the shell opening when the snail withdraws into without shells. the shell. The popular food snails, known as escargot, are land snails of the species Helix pomatia. Many mollusks, including snails, have a radula, an organ in the throat with rows of sharp teeth that rasp off bits of Snail shells are univalves, coiled in a clockwise spiral. -

TDR BCV-SCH SIH 84.3 Eng.Pdf (3.396Mb)

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION ' TDR/BCV-SCH/SIH/84. 3 :/ ENGLISH ONLY ., UNDP/WORLO BANK/WHO SPECIAL PROGRAMME FOR ! ' RESEARCH AND TRAINING IN TROPICAL DISEASES I : { ' .., : ' ; Geneva, 25-27 January 1984 r' ( l{ . •, REPORT OF AN INFORMAL CONSULTATION ON RESEARCH ON / I THE BIOLOGICAL--CONTROL OF SNAIL INTERMEDIATE HOSTS I CONTENTS SUMMARY 2 1 . INTRODUCTION AND OB JECTIVES 2 2. BACKGROUND • J 2.1 Current Schistosomiasis Contr ol Strategy 3 2.2 Present Role of Snail Host Contr ol 4 2.3 Present Status of Research and Use of Snail Host Antagonists • • . • 5 J. THEORETICAL BASIS FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL STRATEGIES 7 3.1 Major Attributes Affecting Choice of Biocontrol Agent 8 4. SAFETY FACTORS • • 9 Table I Possible Safety Factors for Consideration Before Introduction of Exotic Biological Control Agents 11 Table II Schematic Rep r esentation of Development Testing of a Biological Control Agent 12 5. AVAILABLE ANTAGONISTS: CURRENT KNOWLEDGE AND FUTURE PROSPECTS 5.1 Microbial Pathogens 13 5. 2 Parasites . 14 5.3 Predator s 15 5. 4 Competitors . 16 6. COSTS . 19 7. TRAINING, RESEARCH COORDINATION AND INFORMATION TRANSFER 19 7.1 Training • ....• 19 7. 2 Research Coordination 20 7.3 Information Transfer 20 This report contains the collective views of an International group Ce rapport exprime les vues collectives d'un groupe international of experts convened by the UNOP/WOR LD BA NK/ WHO SPECIAL d'experts riuni par le PROGRAMME SPECIAl PNUO/ BANQU E PROGRA MME FOR RESEARCH AND TRA INING IN TROPICA l MONOIALE/OMS DE RECHERCHE ET DE FORMATION DISEASES (TO RI. It does not ntcessarily reflett the views of CONCERNANT lES MAlAD IES TROPICAlES (TO R).