Latest AIJAC Submission On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Oakley Sent: Thursday, 15 May 2008 5:08 PM To: Joanne Puccini Subject: RE: Media Watch Query

From: Alan Oakley Sent: Thursday, 15 May 2008 5:08 PM To: Joanne Puccini Subject: RE: Media watch query Hi Joanne, Thanks for the inquiry. I never discuss why something is or isn't published, suffice to say it's called editing and it happens daily. I don't discuss the performance of individual journalists in a public forum; I find it more constructive to talk to them. I don't discuss how reporters are briefed for assignments; only they need to know. regards, Alan From: Joanne Puccini Sent: Thursday, 15 May 2008 12:54 PM To: Alan Oakley; Sue Ritchie Subject: Media watch query Alan Oakley Editor The Sydney Morning Herald By email 15 May 2008 Dear Alan, On Saturday May 10th, The Age published a lengthy "farewell" report by Fairfax's departing Middle East correspondent Ed O'Loughlin. We understand that the same piece, albeit perhaps subbed somewhat differently, was due to be published in the Sydney Morning Herald's News Review section the same day. However, it did not appear and has not been published subsequently in the Herald. - Could you tell us why you decided not to run this report in The Sydney Morning Herald? There has been frequent criticism of Mr O’Loughlin’s reporting by some supporters of Israel, who appear to believe that he is overly critical of Israel and the IDF, overly sympathetic to the Palestinian point of view, and insufficiently critical of Hamas. (For example, by Michael Danby MP; Mr Tzvi Fleischer, Editor-in-Chief of AIJAC’s Australia/Israel Review; and by AIJAC’s Jamie Hyams, to name a few.) - Did these criticisms of his reporting by the so-called “Jewish/Israel lobby” in any way influence your decision not to run Ed O'Loughlin's final report? Shortly after the announcement of his appointment to replace Ed O’Loughlin as Fairfax’s Jerusalem-based Middle East correspondent, Jason Koutsoukis was reported by the Australian Jewish News as saying: “There's two sides to every story and I think we've got to tell both sides. -

Law Review L

Adelaide Adelaide Law Law ReviewReview 2015 2015 Adelaide Law Review 2015 TABLETABLE OF OF CONTENTS CONTENTS ARTICLES THEArronTHE 2011 Honniball 2011 JOHN JOHN BRAY BRAY ORATIONPriv ORATIONate Political Activists and the International Law Definition of Piracy: Acting for ‘Private Ends’ 279 DavidDavid Irvine Irvine FreeFrdomeedom and and Security: Security: Maintaining Maintaining The The Balance Balance 295 295 Chris Dent Nordenfelt v Maxim-Nordenfelt: An Expanded ARTICLESARTICLES Reading 329 THETHE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF OF ADELAIDE ADELAIDE JamesTrevorJames Allan Ryan, Allan and andProtecting Time Time and and Chance the Chance Rights and and theof the ThosePrevailing Prevailing with Orthodoxy Dementia Orthodoxy in in ADELAIDEADELAIDE LAW LAW REVIEW REVIEW AnthonyBruceAnthony Baer Senanayake Senanayake Arnold ThroughLegalLegal Academia AcademiaMandatory Happeneth Happeneth Registration to Themto Them of All All — —A StudyA Study of theof the Top Top Law Law Journals Journals of Australiaof Australia and and New New Ze alandZealand 307 307 ASSOCIATIONASSOCIATION and Wendy Bonython Enduring Powers? A Comparative Analysis 355 LaurentiaDuaneLaurentia L McOstler McKessarKessar Legislati Three Three Constitutionalve Constitutional Oversight Themes of Themes a Bill in theofin theRights: High High Court Court Theof Australia:of American Australia: 1 SeptemberPerspective 1 September 2008–19 2008–19 June June 201 20010 387347347 ThanujaKimThanuja Sorensen Rodrigo Rodrigo To Unconscionable Leash Unconscionable or Not Demands to Demands Leash -

Digital Edition

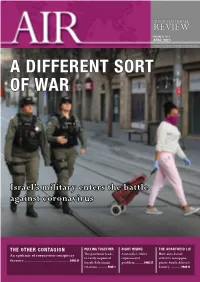

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

Australia's Relations with Iran

Policy Paper No.1 October 2013 Shahram Akbarzadeh ARC Future Fellow Australia’s Relations with Iran Policy Paper 1 Executive summary Australia’s bilateral relations with Iran have experienced a decline in recent years. This is largely due to the imposition of a series of sanctions on Iran. The United Nations Security Council initiated a number of sanctions on Iran to alter the latter’s behavior in relation to its nuclear program. Australia has implemented the UN sanctions regime, along with a raft of autonomous sanctions. However, the impact of sanctions on bilateral trade ties has been muted because the bulk of Australia’s export commodities are not currently subject to sanctions, nor was Australia ever a major buyer of Iranian hydrocarbons. At the same time, Australian political leaders have consistently tried to keep trade and politics separate. The picture is further complicated by the rise in the Australian currency which adversely affected export earnings and a drought which seriously undermined the agriculture and meat industries. Yet, significant political changes in Iran provide a window of opportunity to repair relations. Introduction Australian relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran are complicated. In recent decades, bilateral relations have been carried out under the imposing shadow of antagonism between Iran and the United States. Australia’s alliance with the United States has adversely affected its relations with Iran, with Australia standing firm on its commitment to the United States in participating in the War on Terror by sending troops to Afghanistan and Iraq. Australia’s continued presence in Afghanistan, albeit light, is testimony to the close US-Australia security bond. -

Australia: Background and U.S

Order Code RL33010 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Australia: Background and U.S. Relations Updated April 20, 2006 Bruce Vaughn Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Australia: Background and U.S. Interests Summary The Commonwealth of Australia and the United States are close allies under the ANZUS treaty. Australia evoked the treaty to offer assistance to the United States after the attacks of September 11, 2001, in which 22 Australians were among the dead. Australia was one of the first countries to commit troops to U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. In October 2002, a terrorist attack on Western tourists in Bali, Indonesia, killed more than 200, including 88 Australians and seven Americans. A second terrorist bombing, which killed 23, including four Australians, was carried out in Bali in October 2005. The Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, was also bombed by members of Jemaah Islamiya (JI) in September 2004. The Howard Government’s strong commitment to the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq and the recently negotiated bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Australia and the United States have strengthened what were already close ties between the two long-term allies. Despite the strong strategic ties between the United States and Australia, there have been some signs that the growing economic importance of China to Australia may influence Australia’s external posture on issues such as Taiwan. Australia plays a key role in promoting regional stability in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. -

The Asia-Pacific Epistemic Community’ Björn Jerdén*

Review of International Studies, Vol. 43, part 3, pp. 494–515. doi:10.1017/S0260210516000437 © British International Studies Association 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. First published online 19 January 2017 . Security expertise and international hierarchy: the case of ‘The Asia-Pacific Epistemic Community’ Björn Jerdén* Asia Programme Director, Swedish Institute of International Affairs https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms Abstract Many states partially relinquish sovereignty in return for physical protection from a more powerful state. Mainstream theory on international hierarchies holds that such decisions are based on rational assess- ments of the relative qualities of the political order being offered. Such assessments, however, are bound to be contingent, and as such a reflection of the power to shape understandings of reality. Through a study of the remarkably persistent US-led security hierarchy in East Asia, this article puts forward the concept of the ‘epistemic community’ as a general explanation of how such understandings are shaped and, hence, why states accept subordinate positions in international hierarchies. The article conceptualises a transnational and multidisciplinary network of experts on international security – ‘The Asia-Pacific Epistemic Community’–and demonstrates how it operates to convince East Asian policymakers that the current US-led social order is the best choice for maintaining regional ‘stability’. -

Tibet Gets a Warmer Reception As World Wakes to Beijing's Methods by Peter Hartcher Sydney Morning Herald 11 December 2018

Tibet gets a warmer reception as world wakes to Beijing's methods By Peter Hartcher Sydney Morning Herald 11 December 2018 The leader of Tibet's government-in-exile has been telling his story about Bob Carr around the world for years and always gets a laugh. Last week he recounted it during a visit to Parliament House in Canberra. Ever since the Dalai Lama split his job into two some years ago, remaining spiritual leader of the Tibetans in exile and handing over the political leadership to be elected from among the free Tibetans, Lobsang Sangay has been their President. In 2013 Sangay visited Canberra and a reporter asked him whether Carr, Australia's then foreign affairs minister, would be meeting him. It's always a delicate matter. A government that meets the Dalai Lama or Sangay risks the wrath of the Chinese Communist Party, which has claimed to be the sole representative of the Tibetan people ever since its army invaded Tibet in 1950. "I said I'd love to, but I haven't asked for a meeting", not wanting to put Carr in a difficult position, he recalled last week. "I'm sure that, given the choice, Bob Carr would like to meet because that's the Buddhist culture – we like to believe people are good." Later in his visit, the Tibetan leader was riding the lift from Parliament's subterranean carpark into the building when the lift stopped. "The doors open and Bob Carr walks in," the Harvard-educated legal scholar tells me. The Labor backbencher Michael Danby, Sangay's escort for the visit, introduced the two men in the lift: "I had to decide at that moment whether to extend my hand or not. -

Speech for Justice for Palestinians: a Human Rights Conundrum

XVI: 2019 nr 4 DOI: 10.34697/2451-0610-ksm-2019-4-001 e-ISSN 2451-0610 ISSN 1733-2680 Linda Briskman prof., Western Sydney University ORCID: 0000-0002-5328-0339 Scott Poynting prof., Western Sydney University ORCID: 0000-0002-0368-2751 SPEECH FOR JUSTICE FOR PALESTINIANS: A HUMAN RIGHTS CONUNDRUM Introduction The question of free speech is vigorously debated in Australia and globally. As academics, we are interested in limitations to free speech when it serves the inter- ests of powerful dominant interests. We are also concerned about the concomitant right of academic freedom that purports to enable scholars to speak publicly and stridently about issues facing contemporary society, including those that are con- tested and where debates are heated. We do not limit our interest to the academic sphere as pervasive institutional barriers extend to other domains such as media and parliaments. Our paper specifi cally focuses on free-speech constriction in the Israel-Palestine confl ict of ideas. We examine this constraint in three ways in the Australian context: academic freedom, media freedom and freedom of political representation and expression. We confi ne our exploration to an Australian per- spective, while recognizing that similar patterns occur in other nations. 14 LINDA BRISKMAN, SCOTT POYNTING What makes Israel-Palestine a compelling exemplar is that what endures is not just active and polarized debates, but deliberate attempts by powerful sectors of societies to stifl e the voices of those who dissent from dominant discourses. The irony is that the universally enshrined human right to free speech is removed from those who speak out for human rights. -

Federal & State Mp Phone Numbers

FEDERAL & STATE MP PHONE NUMBERS Contact your federal and state members of parliament and ask them if they are committed to 2 years of preschool education for every child. Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Aston Alan Tudge Liberal (03) 9887 3890 Hotham Clare O’Neil Labor (03) 9545 6211 Ballarat Catherine King Labor (03) 5338 8123 Indi Catherine McGowan Independent (03) 5721 7077 Batman Ged Kearney Labor (03) 9416 8690 Isaacs Mark Dreyfus Labor (03) 9580 4651 Bendigo Lisa Chesters Labor (03) 5443 9055 Jagajaga Jennifer Macklin Labor (03) 9459 1411 Bruce Julian Hill Labor (03) 9547 1444 Kooyong Joshua Frydenberg Liberal (03) 9882 3677 Calwell Maria Vamvakinou Labor (03) 9367 5216 La Trobe Jason Wood Liberal (03) 9768 9164 Casey Anthony Smith Liberal (03) 9727 0799 Lalor Joanne Ryan Labor (03) 9742 5800 Chisholm Julia Banks Liberal (03) 9808 3188 Mallee Andrew Broad National 1300 131 620 Corangamite Sarah Henderson Liberal (03) 5243 1444 Maribyrnong William Shorten Labor (03) 9326 1300 Corio Richard Marles Labor (03) 5221 3033 McEwen Robert Mitchell Labor (03) 9333 0440 Deakin Michael Sukkar Liberal (03) 9874 1711 McMillan Russell Broadbent Liberal (03) 5623 2064 Dunkley Christopher Crewther Liberal (03) 9781 2333 Melbourne Adam Bandt Greens (03) 9417 0759 Flinders Gregory Hunt Liberal (03) 5979 3188 Melbourne Ports Michael Danby Labor (03) 9534 8126 Gellibrand Timothy Watts Labor (03) 9687 7661 Menzies Kevin Andrews Liberal (03) 9848 9900 Gippsland Darren Chester National -

The Hon Michael Danby MP Is the Federal Member of Parliament For

The Hon Michael Danby MP is the federal Member of Parliament for Melbourne Ports in the Australian House of Representatives, representing the Australian Labor Party (ALP). He is a 6-term member, having been elected in 1998 and re-elected in 2001, 2004, 2007, 2010 and 2013. Since his election, his main areas of interest have been foreign affairs, defence and national security, immigration, electoral matters, human rights and the environment. Michael is known for speaking out on international human rights issues. He meets frequently with representatives of the Tibetan exile community and led the first ever Australian Parliamentary group to Dharamsala in Northern India to meet with the Dalai Lama and the Central Tibetan Administration (often referred to as the Tibetan Government in Exile). Michael also has close links with the Uyghur community, having helped organise the visit of the Uyghur leader Rebiya Kadeer to Australia for the Melbourne International Film Festival in August 2009. Michael also has a keen interest in human rights issues in Africa: he has links with the Australian Darfuri community and was the official Australian representative to the independence celebration of South Sudan. He also takes a keen interest in Middle East Affairs and supports Australia’s (bipartisan) position of support for a two state-solution to the Israel/Palestine conflict. Michael is also a member of the Steering Committee of the World Movement for Democracy. In the Parliament of Australia, Michael is currently the Shadow Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the Opposition, Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for the Arts, Deputy Chair of the House Standing Committee on Procedure and a member of the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. -

Hamerkaz ACT Jewish Community Magazine December 2015 | Kislev / Tevet 5776

המרכז HaMerkaz ACT Jewish Community Magazine December 2015 | Kislev / Tevet 5776 ● Channukah on the Hill ● Life Membership Awards ● The Burdens and Joys of Membership ● The Sculpture of Jeremiah Issue 532 31 National Circuit, Forrest ACT 2603 | PO Box 3105, Manuka ACT 2603 (02) 6295 1052 | [email protected] www.actjc.org.au COVER PHOTO: Channukah on the Hill with hosts Michael Danby MP; Josh Frydenberg MP and Mark Dreyfus MP. The ACT Jewish Community is celebrating its 64th anniversary this year. We are a pluralistic, member-run community consisting of Orthodox and Progressive and Secular Jews. We offer educational, religious, social and practical Assistance and Services for all ages, including a playgroup for very young children, a Sunday School (Cheder) for children and teens, Bar and Bat Mitzvah classes, youth groups, social events for young adults, Hebrew and Talmud classes for adults of all ages, prayer services, arranging kosher food in Canberra including supermarkets, Jewish Care (practical assistance, prison and hospital visits), guest lectures, Shabbat and Jewish festival celebrations, end-of-life support including tahara, and more. We look forward to seeing you at the Centre and at our functions, and welcoming you into our community of friends. Please remember that the views expressed in HaMerkaz by individual authors do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the ACT Jewish Community. PAGE 2 | Issue 532 HaMerkaz December 2015 | Kislev / Tevet 5776 Contents Regular Community Reports 04 From the Editor's -

Dear President Kroger and Fellow Victorian Liberal Party Administrative Committee Members (And a Few Others on BCC), As You

From: Stephen Mayne [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, 2 August 2018 4:31 PM To: '[email protected]' Cc: '[email protected]' Subject: Decision to be taken at Admin Committee tonight Dear President Kroger and fellow Victorian Liberal Party Administrative Committee members (and a few others on BCC), As you may be aware by now, the following story appeared in Crikey today about your meeting tonight. A text version is reproduced below if you are unable to get past the paywall. Also relevant is this earlier story which appeared in The Manningham Leader on July 14, outlining the scenario that if Australia’s soon to be longest serving incumbent Federal MP, Kevin Andrews, is centrally endorsed in Menzies to serve for more than 30 years, I will run as an independent against him at the 2019 Federal election. Please note that my main interest in securing the departure of Kevin Andrews relates to his positions on gambling. Australians lose more per capita gambling than any other people on earth. The total losses will exceed $25 billion in 2018, which will cause enormous damage to families, along with more crime, family violence and suicide, not to mention the loss of potential revenue for small business which have to deal with $25 billion less circulating throughout the economy each year. I am a professional advocate for gambling reform and Mr Andrews was the shadow Minister who helped defeat the proposed Andrew Wilkie reforms to poker machines in 2011. Subsequent to that move, Mr Andrews has inappropriately accepted $40,000 in campaign donations from Clubs NSW, an organisation based in Sydney which operates as ruthlessly to promote gambling as the NRA does in relation to guns in the United States.