CHAPTER 8 Natural and Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laws of Wisconsin Territory

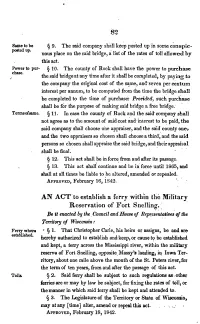

82 Same to be § 9. The said company shall keep posted up in some conspic- posted up. uous place on the said bridge, a list of the rates of toll allowed by this act. Power to pur- § 10. The county of Rock shall have the power to purchase chase. the said bridge at any time after it shall be completed, by paying to the company the original cost of the same, and seven per centum interest per annum, to be computed from the time the bridge shall be completed to the time of purchase: Provided, such purchase shall be for the purpose of making said bridge a free bridge. Terms ofsame. § 11. In case the county of Rock and the said company shall not agree as to the amount of said cost and interest to be paid, the said company shall choose one appraiser, and the said county one, and the two appraisers so chosen shall choose a third, and the said persons so chosen shall appraise the said !midge, and their appraisal shall be final. § 12. This act shall be in force, from and after its passage. § 13. This act shall continue and be in force until 1865, and shall at all times be liable to he altered, amended or repealed. APPROVED, February 16, 1S42. AN ACTA() establish a ferry within the Military Reservation of Fort Snelling.. Be it enacted by the Council and House of Representatives of the Territory of Wisconsin : Ferry where ' § 1. That Christopher Carle, his heirs or assigns, be and are established. hereby authorized to establish and keep, or cause to be established and kept, a ferry across the Mississippi river, within the military reserve of Fort Snelling, opposite, Massy's landing, in, Iowa Ter- ritory, about one mile above the mouth of the St. -

Memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wisconsin, Praying That the Title of the Menomonie Indians to Lands Within That Territory May Be Extinguished

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 1-28-1839 Memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wisconsin, praying that the title of the Menomonie Indians to lands within that territory may be extinguished Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Doc. No. 148, 25th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1839) This Senate Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , ~ ' ' 25th CoNGREss, [SENATE.] [ 14-8] 3d Session. '. / o.r Til~ t.EtitsLA.Tff:E .Ass·EMBtY oF, THE TERRITORY oF W'ISCONSIN, l'RAYING That the title of the MenQ'!JfQ,~zie IJ_y]j(J.1JS. tq ?fJnds within that Territory ni'ay be extinguished. JA~u~RY 28, ~839. Referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs, and ordered to be printed. To the honorable the Senate and House of Representotives of the United States of America in Congress assembled: The memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the 'rerritory of Wisconsin RESPECTFULLY REPRESENTS : That the title of the Menomonie nation of Indians is yet unextinguished to that portion of our Territory lying on the northwest side of, and adjacent to, the Fox river of'Green bay, from the portage of the Fox and Wisconsin _rivers to the mouth of Wolf river. -

American Indian Treaties in the Territorial Courts: a Guide to Treaty Citations from Opinions of the United States Territorial Court Systems

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 9-2009 American Indian Treaties in the Territorial Courts: A Guide to Treaty Citations from Opinions of the United States Territorial Court Systems Charles D. Bernholz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Bernholz, Charles D., "American Indian Treaties in the Territorial Courts: A Guide to Treaty Citations from Opinions of the United States Territorial Court Systems" (2009). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 196. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. American Indian Treaties in the Territorial Courts: A Guide to Treaty Citations from Opinions of the United States Territorial Court Systems Charles D. Bernholz Love Memorial Library, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Abstract Before statehood, the Territorial courts—empowered by the legislation that created each Territory— had the responsibility of adjudicating many questions, including those arising over the interpretation of American Indian treaties. This article identifies 150 citations, to 79 ratified Indian treaties or supple- mental articles, in 55 opinions between the years 1846 and 1909 before 12 Territorial court systems. The cases listed here mark the significance of these documents before these and later courts; many of these proceedings foreshadowed some of today’s dilemmas between the tribes and others. -

Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. the Territorial

COlLECTIONS If OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE TERRITORIAL CENSUS FOR'1836. OF WISCONSIN BY THE EDI'.rOR. In th~ act of Congress approved April 20, 1836, establis4 ing the Territorial government of Wisconsin, it was pro· vided (sec. 4) that "Previously to the first election" the governor of the Territory shall cause t4e census or enu- '. meration of the inhabitants of the. several counties in the EDITED AND ANNOTATED territory to be taken or made by the sheriffs of said coun By REUBEN GOLD THWAITES ties, respectively, and returns thereof made by the said Corresponding Secretary of the Society sheriffs, to the governor." Upon the basis of this censlls, . the governor was to make an apportionment "as nearly .equal as practicable among the several counties, for the election of the council and representatives, giving to .each' VOL. XIII section of th~ territory representation in the ratio of its population, Indians excepted, as near as may be." The returns of this first Wisconsin census, taken in J\lly, 1836, are preserved in the office of the secretary of state. No printed blanks were furnished; the sheriffs were in .structed simply to report, in writing, the, names of heaus pf white families, with the number of persons in each family, divided into the usual four groups: c. ,: ;", I. No.' of males under 21 years. II. " "females " III. " males over ' MADISON .'IV., "females" DEMOCRAT PRINTING COMPANY, STATE PRINTER 'The returns made to the governor were in tabular form, 1895 'abd for the most patt on 'ordinary foolscap paper. In the , of Cr,awford -County, the enterprising sheriff exceeded • I WISCONSIN HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS. -

201409 BCHS Nwsltr

THE HISTORICAL BULLETIN September 2014 Vol. XXXIII, No. 3 A newsletter by the Brown County Historical Society dedicated to the preservation of Brown County history. 2013 H ISTORIC PRESERVATION AWARD WINNER PACKERS HERITAGE TRAIL by Jerry Abitz Green Bay has a unique relationship with its professional football team. Fan loyalty to their team is the envy of the rest of the league. If you don't think so, think of the long, long list of people waiting for, potentially, years and years to get season tickets. Think, too, of the welcome home cele- brations that followed the 13 NFL Championship seasons (which in- clude four Super Bowls!) with tens of thousands of fans lining the streets in the heart of Wisconsin's frigid win- ters. People here consult the Packer schedule before they pick a date for Left: Trailhead for the Packers Heritage Trail on the Neville Public Museum their event to avoid conflicts. A recent grounds with the Fox River in the background. The Trail starts here, across meeting Dousman Street from the former Chicago & North Western railway station depot (2014). Right: Map of the Packers Heritage Trail on the grounds of Inside this issue: of stock- the Neville Public Museum (2014). Photos by Jerry Abitz. holders Packers Heritage Trail 2 resulted in more than 15,000 people showing (cont.) up on a workday at Lambeau Field; some came Historical Markers 3 from as far away as Florida. The aura of this Historical Markers (cont.) 4 team is like no other. So, it is no surprise that someone came Events 5 up with the idea of a Packers Heritage Trail. -

The Birth of Minnesota / William E. Lass

pages 256-266 8/20/07 11:39 AM Page 267 TheThe BBIRTHIRTH ofof MMINNESOTAINNESOTA tillwater is known as the WILLIAM E. LASS birthplace of Minnesota, primarily because on August 26, 1848, invited Sdelegates to the Stillwater Conven- tion chose veteran fur trader Henry Hastings Sibley to press Minnesota’s case for territorial status in Con- gress. About a week and a half after the convention, however, many of its members were converted to the novel premise that their area was not really Minnesota but was instead still Wisconsin Territory, existing in residual form after the State of Wisconsin had been admitted to the union in May. In a classic case of desperate times provoking bizarre ideas, they concluded that John Catlin of Madison, the last secretary of the territory, had succeeded to the vacant territorial governorship and had the authority to call for the Dr. Lass is a professor of history at Mankato State University. A second edi- tion of his book Minnesota: A History will be published soon by W. W. Norton. SUMMER 1997 267 MH 55-6 Summer 97.pdf 37 8/20/07 12:28:09 PM pages 256-266 8/20/07 11:39 AM Page 268 election of a delegate to Congress. As a willing, Stillwater–St. Paul area. The politics of 1848–49 if not eager, participant in the scheme, Catlin related to the earlier dispute over Wisconsin’s journeyed to Stillwater and issued an election northwestern boundary. Minnesota had sought proclamation. Then, on October 30, the so- an identity distinct from Wisconsin beginning called Wisconsin Territory voters, who really with the formation of St. -

Our County, Our Story; Portage County, Wisconsin

Our County Our Story PORTAGE COUNTY WISCONSIN BY Malcolm Rosholt Charles M. White Memorial Public LibrarJ PORTAGE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS STEVENS POINT, \VISCONSIN 1959 Copyright, 1959, by the PORTAGE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AT WORZALLA PUBLISHING COMPANY STEVENS POINT, WISCONSIN FOREWORD With the approach of the first frost in Portage County the leaves begin to fall from the white birch and the poplar trees. Shortly the basswood turns yellow and the elm tree takes on a reddish hue. The real glory of autumn begins in October when the maples, as if blushing in modesty, turn to gold and crimson, and the entire forest around is aflame with color set off against deeper shades of evergreens and newly-planted Christmas trees. To me this is the most beautiful season of the year. But it is not of her beauty only that I write, but of her colorful past, for Portage County is already rich in history and legend. And I share, in part, at least, the conviction of Margaret Fuller who wrote more than a century ago that "not one seed from the past" should be lost. Some may wonder why I include the names listed in the first tax rolls. It is part of my purpose to anchor these names in our history because, if for no other reas on, they were here first and there can never be another first. The spellings of names and places follow the spellings in the documents as far as legibility permits. Some no doubt are incorrect in the original entry, but the major ity were probably correct and since have changed, which makes the original entry a matter of historic significance. -

FIFTY: the Stars, the States, and the Stories All Story Descriptions The

FIFTY: The Stars, the States, and the Stories All Story Descriptions The United States of America is a magnificent experiment. It is a nation built on a dream of a better future, on equality, and on true freedom. But what does that really look like? In this collection of stories, we learn about the American Experiment through the experience of “regular folk” — one from each state, plus every district and territory. Rebels, industrialists, foresters, farmers, and immigrants from every corner of the planet and Native folk who have been here for a very long time – we will meet them all in a moment of true citizenship: when they make the American Experiment their own. A note for all the stories — these stories are all historical fiction — pulling from real historical and biographical facts — but “sparkled” into a narrative that engages and inspires. Though this is historical fiction and the characters have been developed to accommodate a story, their attributes and development may be useful as reference points and inspirations. Collection One: Collection One contains the following states: Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, North Carolina, and Rhode Island Delaware: People Like Me Richard Heath, administrator for the Quaker businessman William Penn, was set with the grueling task of delivering notices to anyone who was living on land now owned by his employer. When he encounters Old Hannu, a "Forest Finn," and his Lenape-Dutch grand-daughter, his idea of "land ownership" is fundamentally challenged. Pennsylvania: Three Men and a Bell On September 16, 1777, three men — a sociable young Mennonite farmer, a seasoned old doorman of poor health, and an injured African-American carpenter — were given the grand task of hiding a uniquely symbolic .. -

Minnesota State Research Guide Family History Sources in the North Star State

Minnesota State Research Guide Family History Sources in the North Star State Minnesota History The first Europeans to settle Minnesota were the French in the northern parts of the state, but with the Treaty of Paris in 1763 at the end of the French and Indian War, the French ceded those areas to the British. The British lost those areas twenty years later through another Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution. Southwestern Fort Snelling from over the Mississippi River, portions of the state were acquired from U.S., Historical Postcards by the U.S. as part of the Louisiana Purchase. What is now the state of Minnesota has been part of eight different territories—the Northwest Territory, Louisiana Territory, Indiana Territory, Illinois Territory, Michigan Territory, Wisconsin Territory, Iowa Territory, and Minnesota Territory. It was also part of the District of Louisiana prior to the formation of Louisiana Territory. The fur trade attracted Minnesota’s earliest settlers, who traded with Native Americans. Beginning in the 1820s the U.S. government began establishing agencies to control that trade. The St. Peters Indian Agency worked to maintain the peace between 1820 and 1853. Bit-by-bit, treaties ceded Native American lands and displaced the earliest inhabitants of the area. By the 1870s, the lumber business was booming as the expansion of railways and the use of steam power made it possible to export large quantities of white pine to distant markets. The St. Croix region drew loggers and saw mills populated Lake Superior’s shore giving rise to cities like Duluth. -

Territorial Courts and the Law: Unifying Factors in the Development of American Legal Institutions-Pt.II-Influences Tending to Unify Territorial Law

Michigan Law Review Volume 61 Issue 3 1963 Territorial Courts and the Law: Unifying Factors in the Development of American Legal Institutions-Pt.II-Influences Tending to Unify Territorial Law William Wirt Blume University of Michigan Law School Elizabeth Gaspar Brown University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Common Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation William W. Blume & Elizabeth G. Brown, Territorial Courts and the Law: Unifying Factors in the Development of American Legal Institutions-Pt.II-Influences endingT to Unify Territorial Law, 61 MICH. L. REV. 467 (1963). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol61/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TERRITORIAL COURTS AND LAW UNIFYING FACTORS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN LEGAL INSTITUTIONS William Wirt Blume* and Elizabeth Gaspar Brown** Part II. INFLUENCES TENDING To UNIFY TERRITORIAL LAWf ITH the exception of Kentucky, Vermont, Texas, California, W and West Virginia, all parts of continental United States south and west of the present boundaries of the original states came under colonial rule, and were governed from the national capital through territorial governments for varying periods of time. -

The United States

Bulletin No. 226 . Series F, Geography, 37 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES V. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR BOUNDARIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND OF THE SEVERAL STATES AND TERRITORIES WITH AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF ALL IMPORTANT CHANGES OF TERRITORY (THIRD EDITION) BY HENRY G-ANNETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 CONTENTS. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL .................................... ............. 7 CHAPTER I. Boundaries of the United States, and additions to its territory .. 9 Boundaries of the United States....................................... 9 Provisional treaty Avith Great Britain...........................'... 9 Treaty with Spain of 1798......................................... 10 Definitive treaty with Great Britain................................ 10 Treaty of London, 1794 ........................................... 10 Treaty of Ghent................................................... 11 Arbitration by King of the Netherlands............................ 16 Treaty with Grreat Britain, 1842 ................................... 17 Webster-Ash burton treaty with Great Britain, 1846................. 19 Additions to the territory of the United States ......................... 19 Louisiana purchase................................................. 19 Florida purchase................................................... 22 Texas accession .............................I.................... 23 First Mexican cession....... ...................................... 23 Gadsden purchase............................................... -

The Mcmahon Way Newsletter

ISSUE 26.2019 IN THIS ISSUE Norbert Gossens Walleye Tournament / P1 McMAHON Staff News Vandey Hey Joins Board / IHDA Funding / Community Connection P2 Approaching Deadlines P3 Message from President / P4 Success for St. Nicholas Robotics Team The Newsletter of McMAHON Featured Client: Village of Ashwaubenon P5 NEW HIRES Giving Back: Local Fishing Tournament WISCONSIN TAYLOR PATTERSON, EIT Has BIG IMPACT WATER & WASTEWATER DESIGN ENGINEER When Sam Pociask had the idea in 2008 to start a fishing tournament for some of his friends and family, he had no idea how big of an impact it would have on so many KEVIN BONS, EIT lives 12-years later. Named after Sam’s MUNICIPAL & CIVIL ENGINEERING TECH grandfather, the Norbert Gossens Walleye Tournament was born out of the idea that good friends and good fishermen need an excuse to get together once a year. LAURA McCARTHY “Eight years ago, the idea was presented ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT to me to add a charitable component to this tournament,” explains Pociask, GIS Each year since the fundraising Manager/Associate at McMAHON. “At component was added to the tournament, first I was hesitant, until I saw the willing- donations from generous individuals and ness of so many folks to participate.” STEVE HERMAN, PE businesses have increased, providing MUNICIPAL & CIVIL The 12th edition of the Norbert Gossens funds to support charities which have ENGINEER Tournament took place earlier this included Special Olympics of Wisconsin, summer at its usual location, Sam’s home Littlest Tumor Foundation, Valley Kids along the shore of Lake Winnebago in Foundation and myTEAM TRIUMPH. To Neenah.