Ablative Neurosurgical Techniques in the Treatment of Chronic Pain: Overview Timothy R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Think with Flying Colours, Express

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.50.9.1251 on 1 September 1987. Downloaded from Book reviews 1251 The eight biographies of disabled people differences. In the chapter on neirve blocking Intensive Care and Monitoring of the Neuro- with which the book begins demonstrate the procedures it is most refreshing tto see Charl- surgical. Patient (Progress in Neurological author's skill in empathising with individu- ton's cautious approach, criticalI analysis of Surgery Vol 12.) Edited by AM Landolt. als and outlining important aspects of aging methods and results, and warni ngs ("before (Pp 202; $74.00.) Basel: Karger, 1987. with disability. It is sad that there is no bet- embarking upon neurolytic block everyone ter book covering this topic. Why not? As should read the review of rnedico-legal It is unfortunate that this volume, dedicated the author says, saving lives attracts glam- aspects of complications that may follow to Hugo Krayenbuhl with such a good our and funds which are denied to services these procedures"). He states that intra- biography, has suffered the vicissitudes of for the saved. If this is true of spinal injury thecal use ofcold hypertonic saliine and bar- multiple authorship (so frankly acknowl- and poliomyelitis it is no less true of the botage of CSF "can now be regaLrded as his- edged in the editors' preface that it could be beneficiaries ofother miracles: for example a torical curiosities"; of epidural lblock "there taken as a lament upon this type of book); generation of people with spina bifida and is a distinct lack of published (data on the relatively little of the title is covered by the hydrocephalus now being launched into an injection of neurolytic solutions into the epi- contents, and the relationship of the eight adult world which has made no special dural space"; and neurolytic p;aravertebral contributions is seemingly haphazard. -

Neurosurgery

March 10, 2017 St Elizabeth Healthcare 9:02 am Privileges for: Neurosurgery Request ST. ELIZABETH - EDGEWOOD ST. ELIZABETH - FLORENCE ST. ELIZABETH - FT. THOMAS ST. ELIZABETH - GRANT CO. (Surgical & other invasive procedures requiring general anesthetic are not offered) MEC Approval: August 27, 2009; Rev. November 15, 2012, February 27, 2014 Board Approval: September 14, 2009; Rev. January 7, 2013, May 5, 2014 DEPARTMENT APPROVAL ________Approved ________Disapproved ___________________________________________ ________________ Department/Section Chair Signature Date MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS Degree required: MD or DO Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA accredited residency in neurosurgery. Note: For Practitoners (excluding AHPs) who apply for membership after March 2, 2009 be and remain (with a lapse of no longer than one year) board certified in their principal practice specialty, or become and remain (with a lapse of no longer than one year) board certified within six years of completion of their post-graduate medical training. Only those boards recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties or the American Osteopathic Association are acceptable. This board certification requirement does not apply to applicants who on March 2, 2009 were members in good standing on the medical staff of the St. Luke Hospitals or St. Elizabeth Medical Center. PRIVILEGES REQUESTED Pursuant to Bylaws Section 6.1.4, practitioners may exercise the privileges requested and awarded below only at facilities where St. Elizabeth Healthcare offers those services. I. Core Privileges: Core privileges in neurosurgery include the care, treatment or services listed immediately below. I specifically acknowledge that board certification alone does not necessarily qualify me to perform all core privileges or assure competence in all clinical areas. -

Study of Brain Mechanisms in Temporomandibular Disorder

A Magnetoencephalographic (MEG) Study of Brain Mechanisms in Temporomandibular Disorder A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Aurelio Abdalla Alonso, DDS, MS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DR. APOSTOLOS P. GEORGOPOULOS, ADVISER December 2009 © Aurelio Abdalla Alonso, December/2009 Acknowledgments I am thankful to my supervisor, Dr. Apostolos Georgopoulos, whose encouragement, guidance, support, patience and extraordinary mentorship throughout this journey enabled me to develop an understanding of this work. I would like to thank also the facial somesthesia team members: Dr. Art Leuthold for sharing his knowledge on MEG and his help in general; to Dr. Ioannis Koutlas for inviting me to participate in this amazing project, and help during patient collection and processing data; to Dr. Elissaios Karageorgiou for his technical and general help through this journey. My special thank to Dr. Scott Lewis for his time helping during MRI acquisition and consent forms; to Dr. May Tan for her help and patience during my MEG questions. To all Brain Sciences Center members that direct or indirect help me conquer this journey, especially my sincere appreciation to Mrs. Penny Becker and Mrs. Gail Hollstadt that were always there for me when I needed. Dr. Donald Simone, Dr. Alvin Beitz, Dr. Matt Chafee, and Dr. Darryl Hamamoto it was an honor for me to have you as part of my committee, my sincere gratitude. My many thanks to the Oral Biology Program crew: Dr. Mark Herzbeg for his inspirational conversation, and advices; to Michelle Lamere and Ann Hagen for their support during these years. -

Coding Pain Management Services Notes/Comments/Questions

Coding Pain Management Services Audio Seminar/Webinar April 3, 2008 Practical Tools for Seminar Learning © Copyright 2008 American Health Information Management Association. All rights reserved. Disclaimer The American Health Information Management Association makes no representation or guarantee with respect to the contents herein and specifically disclaims any implied guarantee of suitability for any specific purpose. AHIMA has no liability or responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused by the use of this audio seminar, including but not limited to any loss of revenue, interruption of service, loss of business, or indirect damages resulting from the use of this program. AHIMA makes no guarantee that the use of this program will prevent differences of opinion or disputes with Medicare or other third party payers as to the amount that will be paid to providers of service. CPT® five digit codes, nomenclature, and other data are copyright 2007 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. No fee schedules, basic units, relative values or related listings are included in CPT. The AMA assumes no liability for the data contained herein. As a provider of continuing education, the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) must assure balance, independence, objectivity and scientific rigor in all of its endeavors. AHIMA is solely responsible for control of program objectives and content and the selection of presenters. All speakers and planning committee members are expected to disclose to the audience: (1) any significant financial interest or other relationships with the manufacturer(s) or provider(s) of any commercial product(s) or services(s) discussed in an educational presentation; (2) any significant financial interest or other relationship with any companies providing commercial support for the activity; and (3) if the presentation will include discussion of investigational or unlabeled uses of a product. -

Interventional Physiatry

Interventional Physiatry Diagnosis Medical Branch Block & Radiofrequency Ablation Treatment Prepared by: Tufts PM&R Medical staff Overview and indications for procedure: Lumbar Facet joints (also known as the Zygapophysial joints or Z-joints) are paired structures on both side of your spine that allows movement between two vertebrae. When a facet joints are strained (car accident, fall, injuries) ,degenerative changes settles in these joints or there is a shift between two vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) , the joints could become the source of back pain. Pain may be localized to the lower back or radiating to the buttock, posterior hamstring, groin area or to side of the legs (colored figure credit: Nature Reviews Rheumatology 9 , 216-224 , April 2013) . Medial branch block: Pain information from the facet joints travels to the brain via small nerve endings called medial branches. In order to determine whether or not the facet joint are causing pain, medial branch nerves could be diagnostically blocked and patient can determine whether or not there was a changes in their pain after the procedure. Medial branch block (MBB) is performed twice to confirm the correct diagnoses and the correct number of facets contributing to pain. Clinicians are looking for improvement of pain between 50 - 100% after each diagnostic block. When patient experiences significant reduced pain with diagnostic medical branch injections on 2 separate occasions, he/ she is considered a good candidate to proceed to radiofrequency ablation treatment. Radiofrequency ablation treatment: This procedure is performed after diagnostic medial branch injection is performed and it is determined (with a reasonable degree of certainty) that facet joints are the source of individuals back pain. -

Endoscopic Rhizotomy for Chronic Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Pain

Xue et al. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2020) 15:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-019-1533-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Endoscopic rhizotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain Yuntao Xue1, Tao Ding1* , Dajie Wang2, Jianli Zhao3, Huilin Yang4, Xiaofeng Gu1, Dehong Feng1, Yafeng Zhang5, Hao Liu6, Fenglin Tang1, Wanyi Wang1, Miao Lu1 and Chao Wu7 Abstract Background: Chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain is a common cause of chronic low back pain. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is one of the effective management options; however, the results from the traditional RFA need to be improved in certain cases. The aim of this study is to investigate the effect of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation under endoscopic guidance (ERFA) for chronic low back pain secondary to facet joint arthritis. Methods: This is a prospective study enrolled 60 patients. The cases were randomized into two groups: 30 patients in the control group underwent traditional percutaneous radiofrequency ablation, others underwent ERFA. The lumbar visual analog scale (VAS), MacNab score, and postoperative complications were used to evaluate the outcomes. All outcome assessments were performed at postoperative 1 day, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Results: There was no difference between the two groups in preoperative VAS (P > 0.05). VAS scores, except the postoperative first day, in all other postoperative time points were significantly lower than preoperative values each in both groups (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the two groups in VAS at 1 day, 1 month, and 3 months after surgery (P > 0.05). However, the EFRA demonstrated significant benefits at the time points of 3 months and 6 months (P > 0.05). -

Diffusion Tensor Imaging for Assessment of Microstructural

Chen et al. BMC Neurology (2019) 19:62 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1295-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Diffusion tensor imaging for assessment of microstructural changes associate with treatment outcome at one-year after radiofrequency Rhizotomy in trigeminal neuralgia Shu-Tian Chen1, Jen-Tsung Yang2, Hsu-Huei Weng1, Hsueh-Lin Wang1, Mei-Yu Yeh3 and Yuan-Hsiung Tsai1* Abstract Background: Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is characterized by facial pain that may be sudden, intense, and recurrent. Neurosurgical interventions, such as radiofrequency rhizotomy, can relieve TN pain, but their mechanisms and effects are unknown. The aim of the present study was to investigate the microstructural tissue changes of the trigeminal nerve (TGN) in patients with TN after they underwent radiofrequency rhizotomy. Methods: Thirty-seven patients with TN were recruited, and diffusion tensor imaging was obtained before and two weeks after radiofrequency rhizotomy. By manually selecting the cisternal segment of the TGN, we measured the volume of the TGN, fractional anisotropy (FA), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD). The TGN volume and mean value of the DTI metrics of the post-rhizotomy lesion side were compared with those of the normal side and those of the pre-rhizotomy lesion side, and they were correlated to the post-rhizotomy visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores after a one-year follow-up. Results: The alterations before and after rhizotomy showed a significantly increased TGN volume and FA, and a decreased ADC, AD, and RD. The post-rhizotomy lesion side showed a significantly decreased TGN volume, FA, and AD compared with the normal side; however, no significant difference in the ADC and RD were found between the groups. -

LETTERS to the EDITOR. Middle Cerebral Artery Tortuosity Associated

J Neurosurg 130:1763–1788, 2019 Neurosurgical Forum LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Middle cerebral artery tortuosity tective factors against aneurysm formation.” Nevertheless, according to that explanation, it can be inferred that the associated with aneurysm incidence of aneurysms in patients with local tortuosity development should be decreased rather than increased. Therefore, it would be better for the authors to provide an in-depth ex- planation about the above results and arguments. TO THE EDITOR: We read with great interest the ar- Second, the authors stated, “There are a few rare ge- ticle by Kliś et al.2 (Kliś KM, Krzyżewski RM, Kwinta netic syndromes that are linked to the presence of vessel BM, et al: Computer-aided analysis of middle cerebral tortuosity, such as artery tortuosity syndrome or Loeys- artery tortuosity: association with aneurysm develop- Dietz syndrome.” The genetic syndromes they mention ment. J Neurosurg [epub ahead of print May 18, 2018; are systemic lesions involving multiple parts of vessels DOI: 10.3171/2017.12.JNS172114]). The authors conclude of the body and therefore often involve multiple intracra- that “an increased deviation of the middle cerebral artery nial aneurysms.1,3,5 However, this article did not provide (MCA) from a straight axis (described by relative length detailed information on the characteristics of intracranial [RL]), a decreased sum of all MCA angles (described by aneurysms, for example, the incidence of multiple aneu- sum of angle metrics [SOAM]), a local increase of the rysms, the specific sites of the MCA aneurysms (M1, M2, MCA angle heterogeneity, and an increase in changes in M3, M4), and the size of the aneurysms, etc. -

UCSF Neurological Surgery

UCSF Neurological Surgery 2018 Annual Report Contents 3 Brain Tumor Center 12 Pituitary Disorders 14 Brain and Spinal Injury Center 19 Pain and Peripheral Nerve Disorders 21 Neurospinal Disorders 25 Pediatric Neurosurgery 28 Movement Disorders 31 Vascular Neurosurgery Dear Colleague: 33 Epilepsy This year UCSF was ranked among the top three neurosurgery and neurology programs in the nation by 34 Center for Neural Engineering U.S. News & World Report’s 2018-19 survey of Best and Prostheses Hospitals. UCSF Medical Center was also ranked the best hospital in California and sixth nationwide. Our 35 Department also continues to receive the highest amount Community Extension of NIH funding of any academic neurosurgery program in the nation and our neurosurgery residency program is ranked #1 by Doximity for program reputation. © The Regents of the University of California We also continue to expand our services throughout the Bay Area, with UCSF adult neurosurgery available in Executive Editor: Ilona Garner Marin, Napa and Oakland to provide easy coordination Writer: Andrew Schwartz with local physicians and convenient access for patients Steve Babuljak, Elizabeth Fall, in those areas. We have also recently partnered with Photography: Melissa Lau, Susan Merrell, Barbara Ries, John Muir Health to offer neurosurgery evaluations at the Marco Sanchez, Tom Seawell new Berkeley Outpatient Center, a center for primary and specialty care serving patients in the East Bay. Illustration: Kenneth Xavier Probst I hope you enjoy reading about the clinical and research Design: Victoria Maier Magbilang, highlights from our Department in 2018. I am very proud Aqua Design Studio of the achievements we have made this year in advancing the field of neurosurgery and, as always, would like to thank you for allowing us to partner with you in the care of your patients. -

Neuroimaging Modalities Currently Used

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.52.11.1318 on 1 November 1989. Downloaded from 1318 Book reviews In conclusion: this small book gives a the usefulness of many other types of sur- subject and is written by the best qualified neurosurgical approach to orbital diseases gery. They add "We do agree with Fields' authors. It is difficult to read because it must and tends to be mainly concerned with thought that the neurosurgical management have been difficult to write because the surgical aspects oforbital disease rather than of severe chronic pain remains in general in authors had to doubt politely the en- the wide variety of medical and paediatric an experimental phase in which respect we thusiasms of their friends and colleagues conditions that might affect it. say it resembles closely the non-neurosurg- who insisted that they had the answers where MD SANDERS ical management of such pain". That is bad none exist. news all round because it means that they are PATRICK D WALL not in a position to give us a straight answer Neurosurgical Treatment of Persistent Pain about the effect of surgery on pain. Introduction to Neuroimaging. By WILLIAM W Vol. II Pain and Headache. By JAN M GYBELS, How long does an experimental phase ORRISON, JR. (Pp 384; Illustrations: 489 MD, PhD and WILLIAM H SWEET MD, DSc, last? Let us take facet rhizotomy as an Radiog. Price: £43.50.) Edinburgh: Churchill DHC, FRCS Ed(Hon) Series Editor: Ph L example. This operation has been carried out Livingston, 1989. Gildenberg (Pp 442; Fig: 70; Price: since 1960 on tens of thousands ofback pain US$129.50; £88-20.) S Karger AG, Basel. -

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy (Sdr) St

SELECTIVE DORSAL RHIZOTOMY (SDR) ST. LOUIS CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL • 280 beds, expanding to 473 in 2017 • 3,000 employees • 800 medical staff members • 1,300 auxiliary members and volunteers • More than 30 pediatric subspecialty departments and divisions • Level I Pediatric Trauma Center, the highest level of emergency care available • Serving patients from 50 states and 70 countries • Recognized as one of the Founded in 1879, St. Louis best children’s hospitals in Children’s Hospital is one of the nation by U.S. News the premier children’s hospitals & World Report in the nation. It serves not just the children of St. Louis, but • Has received the nation’s children across the world. The highest honor for nursing hospital provides a full range of excellence, the Magnet pediatric services to the St. Louis designation, from metropolitan area and a primary the American Nurses service region covering six states. Credentialing Center. As the pediatric teaching hospital for Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children’s Hospital offers nationally recognized programs for physician training and research. | 1 | Table of Contents A Life-Changing Procedure ........................................................ 3 Hope for the Future .................................................................... 3 Understanding Muscle Stiffness .................................................. 6 Benefits of Dorsal Rhizotomy ...................................................... 7 Could Your Child Benefit? ......................................................... -

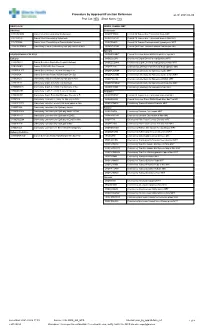

Procedure by Approach/Function Reference As Of: 2021-04-06 Proc Cat: NEU Show Notes: Yes

Procedure by Approach/Function Reference as of: 2021-04-06 Proc Cat: NEU Show Notes: Yes NEURO ACH NEURO CRANIAL MRT ACH Only Endoscopic CRFCRCNEN Cranial Vault Reconstruction Endoscopic CROPITTREM Cranial Pit Tumour Exc Transnasal Endo MRT CRVTRSYN Cranial Vault Remodeling Synostosis CROPITRENM Cranial Pit Tumour Exc Transnasal Endo w Nav MRT CRVTRFOA Cranial Vault Remodelling w Fronto Orbital Advance CROPITHMRI Cranial Pit Tumour Transsphenoid Hypophysect MRT CROCOCENPM Craniotomy Corpus Callosotomy Epilepsy Nav Ped MRT CRSKBTUENM Cranial Skull Base Tumour Excision Endoscopic MRT Epilepsy NEURO CRANIAL EPILEPSY CRSROSAMRT Cranial Stereotax Robot ROSA Depth Elec Epi MRT Epilepsy CROEDEGIM Craniotomy Depth Elec/Grid Impl Epilepsy MRT CRBHIMELC Cranial Burr Hole Depth Elect Implant Epilepsy CROEDEGINM Craniotomy Depth Elec/Grid Impl Epilepsy w Nav MRT CREVROBR Cranial EVD/ROSA Bolt Removal CROEPLEM Craniotomy Lobectom+/-Elec+/-Grid Rem Epilepsy MRT CRSEEGLITT Cranial SEEG w Laser Thermal Therapy LITT CROEPLEAMR Craniotomy Lobectomy for Epilepsy Awake MRT CRSROSA Cranial Stereotax Robot ROSA Depth Elec Epi CROEPLEANM Craniotomy Lobectomy for Epilepsy Awake w Nav MRT CROCOCA Craniotomy Corpus Callosotomy Epilepsy w Nav CROEPEEGM Craniotomy Lobectomy for Epilepsy w ECOG MRT CROEDEGI Craniotomy Depth Elec/Grid Impl Epilepsy CROEPEEGNM Craniotomy Lobectomy for Epilepsy w ECOG Nav MRT CROEDEGIN Craniotomy Depth Elec/Grid Impl Epilepsy w Nav CROEPLENM Craniotomy Lobectomy for Epilepsy w Nav MRT CROEDEGR Craniotomy Depth Elec/Grid Removal Epilepsy