Smart City Indicators: Can They Improve Governance in Croatian Large Cities?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Croatia and Romania 2018

Office of International Education Country Report Croatia and Romania Highlights Romanian scholars consistently collaborate with UGA faculty to produce joint academic output, with main areas of co-publication including Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. From 2007-2017, these collabora- tions resulted in 90 co-publications. The Higher Education Initiative for Southeastern Europe, a collabo- ration between UGA’s Institute of Higher Education and the Center for Advanced Studies in Southeast Europe at the University of Rijeka in Croa- tia, is designed to assist in developing high quality teaching among partner in- stitutions and to stimulate excellence in institutional management and governance through appropriate degree programs and continuing professional education seminars. UGA’s partnership with Babeş Bolyai university in Cluj-Napoca, Romania spans many fields, including Journalism and Chemistry. This latter area of collaboration has resulted in numerous publications in leading chemical journals. January 2018 Croatia Romania Active Partnerships Joint Publications Active Partnerships Joint Publications 3 16 2 90 Visiting Scholars UGA Faculty Visits Visiting Scholars UGA Faculty Visits 1 110 0 8 UGA Students Abroad International Students UGA Students Abroad International Students 39 12 1 4 UGA Education Abroad in Croatia and Romania During the 2016-2017 academic year, 39 UGA students studied in Croatia, while 1 studied in Romania. Currently, UGA students study abroad through the College of Public Health Maymester program in Makarska, Rijeka, Slavonski Brod, and Zagreb, Croatia, and through the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences’ Culture-Centered Communication and Engagement program in Bucharest, Cluj-Mapoca, Salaj County, and Sighisoara, Romania. Academic Collaboration and Exchange in Croatia and Romania Between 2007 and 2017, UGA faculty collaborated to jointly publish 16 and 90 scholarly articles with colleagues in Croatia and Romania, respectively. -

Croatia's Cities

National Development Strategy Croatia 2030 Policy Note: Croatia’s Cities: Boosting the Sustainable Urban Development Through Smart Solutions August 2019 Contents 1 Smart Cities – challenges and opportunities at European and global level .......................................... 3 1.1 Challenges .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Opportunities .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Best practices ............................................................................................................................. 6 2 Development challenges and opportunities of Croatian cities based on their territorial capital .......... 7 3 Key areas of intervention and performance indicators ....................................................................... 23 3.1 Key areas of intervention (KAI)............................................................................................... 23 3.2 Key performance indicators (KPI) ........................................................................................... 24 4 Policy mix recommendations ............................................................................................................. 27 4.1 Short-term policy recommendations (1-3 years) ...................................................................... 27 4.2 Medium-term policy recommendations (4-7 years) ................................................................ -

Fimitic Soih

INFORMATION / CONTACT ADDRESSES FIMITIC Mrs. Marija Stiglic Plitterdorfer Str. 103 D-53173 Bonn - Germany phone: + 49 (0) 228 9359 191 fax: + 49 (0) 228 9359 192 e-mail: [email protected] www.fimitic.org SOIH Mrs. Æeljka ©ariÊ Savska cesta 3, 10 000 Zagreb - Croatia phone: +385 1 48 29 394 fax: +385 1 48 12 551 e-mail: [email protected] LOCAL INFORMATION: • Nearest airport Zagreb-Pleso (international airport) - 20 km, 20 min • Railway station Zagreb, “Glavni kolodvor” - 10 km, 15 min • Zagreb central bus station - 11 km, 20 min LOCAL MEANS OF PUBLIC TRANSPORT • Local bus station - 250 m • Tramway station - 850 m. A Graz 180 km E-59 SL Maribor 117 km H Budapest 372 km SL Gruπkovlje 60 km SESVETE H Nagykanizsa 159 km HR Macelj 60 km ZAPRE©I∆ H Letenye 136 km HR Krapina 50 km E-65 HR GoriËan 136 km E-71 HR Varaædin 98 km Podsused SAMOBOR CENTAR I Ivanja Reka DUGO SELO Jankomir CENTAR II E-70 I Milano 672 km E-70 Æitnjak HR Slavonski Brod 190 km I Trieste 244 km HR Lipovac 260 km SL Ljubljana 134 km Exit “Zapad“ SL Obreæje 14 km HR Bregana 14 km LuËko SAVA RIVER Zagreb Fair Aerodrom PLESO HR Karlovac 55 km E-65 HR Rijeka 180 km HR Split 450 km E-59 VELIKA GORICA AIM OF THE CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Wednesday, November 5, 2003 According to the Statistics there are approximately 30 Million disabled in the European Union and currently accounting 10 percent of all women. Morning • Arrival Preparatory Committe Disabled women are often subject to discrimination. -

The Velika Gorica Cemetery and Related Sites in Continental Croatia

119 The Velika Gorica cemetery and related sites in Continental Croatia !5 Zusammenfassung 1. Introduction Der Velika Gorica-Friedhof und vergleichbare The Urnfield culture in Croatia is represented by grave Fundorte im binnenländischen Kroatien. Der vorlie- finds from the entire time span of this culture (fig. 1). Un- gende Artikel behandelt Grabkontexte aus Verlika Gorica fortunately, most of the cemeteries were not systematically (Zagreb). Der Fundort wurde durch Zufall beim Kiesabbau excavated and they lack closed grave finds and find circum- auf dem Grundstück (Kataster-Nr. 380/2) des Geschäfts- stances. From the early Urnfield culture we have cemeter- manns Nikola Hribar in der Nähe des örtlichen Spitals ent- ies at Virovitica and Sirova Katalena, which were excavated deckt. Es wurden Brandbestattungen sowie mittelalterliche in the 60ies by Ksenija Vinski-Gasparini.1 They formed a Körpergräber gefunden. Der erste Befund wurde von V. basis for the definition of the so-called 1st phase of the Urn- Hoffiller 1909 publiziert. Derselbe Autor analysierte 1924 field culture in Croatia and later the Virovitica group. We die Keramikfunde. Die Funde von Velika Gorica lieferten can also attribute the cemeteries of Moravče2, Drljanovac3 die Definitionsbasis für die jüngere Phase der Urnenfel- and Voćin4 to this group. Furthermore, we can mention derkultur in Nordkroatien. Später wurde die Bezeichnung cemeteries of the Gređani group, excavated by K. Minich- Velika Gorica-Gruppe von Ksenija Vinski-Gasparini ein- reiter in the 80ies,5 in a separate group. Some new sites at geführt. Alle erhaltenen Gräber wurden 2009 von Snježana Mačkovac-Crišnjevi6 and Popernjak7 can also be attributed Karavanić publiziert. -

The War in Croatia, 1991-1995

7 Mile Bjelajac, team leader Ozren Žunec, team leader Mieczyslaw Boduszynski Igor Graovac Srdja Pavlović Raphael Draschtak Sally Kent Jason Vuić Rüdiger Malli This chapter stems in large part from the close collaboration and co-au- thorship of team co-leaders Mile Bjelajac and Ozren Žunec. They were supported by grants from the National Endowment for Democracy to de- fray the costs of research, writing, translation, and travel between Zagreb and Belgrade. The chapter also benefited from extensive comment and criticism from team members and project-wide reviews conducted in Feb- ruary-March 2004, November-December 2005, and October-November 2006. Several passages of prose were reconstructed in summer 2010 to address published criticism. THE WAR IN CROATIA, 1991-1995 ◆ Mile Bjelajac and Ozren Žunec ◆ Introductory Remarks Methodology and Sources Military organizations produce large quantities of documents covering all aspects of their activities, from strategic plans and decisions to reports on spending for small arms. When archives are open and documents accessible, it is relatively easy for military historians to reconstruct events in which the military partici- pated. When it comes to the military actions of the units in the field, abundant documentation provides for very detailed accounts that sometimes even tend to be overly microscopic. But there are also military organizations, wars, and indi- vidual episodes that are more difficult to reconstruct. Sometimes reliable data are lacking or are inaccessible, or there may be a controversy regarding the mean- ing of events that no document can solve. Complicated political factors and the simple but basic shortcomings of human nature also provide challenges for any careful reconstruction. -

Analysis of the Particulate Matter Pollution in the Urban Areas of Croatia, EU †

Proceeding Paper Analysis of the Particulate Matter Pollution in the Urban Areas of Croatia, EU † Martina Habulan 1, Bojan Đurin 2, Anita Ptiček Siročić 1 and Nikola Sakač 1,* 1 Faculty of Geotechnical Engineering, University of Zagreb, HR-42000 Varaždin, Croatia; [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (A.P.S.) 2 Department of Civil Engineering, University North, HR-42000 Varaždin, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Presented at the 3rd International Electronic Conference on Atmospheric Sciences, 16–30 November 2020; Available online: https://ecas2020.sciforum.net/. Abstract: Particulate matter (PM) comprises a mixture of chemical compounds and water particles found in the air. The size of suspended particles is directly related to the negative impact on human health and the environment. In this paper, we present an analysis of the PM pollution in urban areas of Croatia. Data on PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations were measured with nine instruments at seven stationary measuring units located in three continental cities, namely Zagreb (the capital), Slavonski Brod, and Osijek, and two cities on the Adriatic coast, namely Rijeka and Dubrovnik. We analyzed an hourly course of PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations and average seasonal PM2.5 and PM10 con- centrations from 2017 to 2019. At most measuring stations, maximum concentrations were recorded during autumn and winter, which can be explained by the intensive use of fossil fuels and traffic. Increases in PM concentrations during the summer months at measuring stations in Rijeka and Du- brovnik may be associated with the intensive arrival of tourists by air during the tourist season, and lower PM concentrations during the winter periods may be caused by a milder climate consequently resulting in lower consumption of fossil fuels and use of electric energy for heating. -

CROATIA Dino Mujadžević 1 1 Muslim Populations the Last National

CROATIA Dino Mujadžević 1 1 Muslim Populations The last national census from 2011 for the Republic of Croatia provides very reliable data on the number and dispersion of Muslim population and other religions, as well as ethnic groups, in this country. There are 62,977 persons in Croatia who identified themselves as Muslims, which is 1.47% of the total population of 4,284,889. This is a fairly significant increase from 54,814 persons according to 1991 census and 56,777 (1.28% of total population) according to 2001 census.2 According to administra- tive division the largest part of Muslim population resides in the city of Zagreb (18,044; 2,28%) and the following counties (županije):3 Primorsko- goranska (Rijeka; 10,667; 3.60%), Istarska (Pula; 9,965; 4.79%), Sisačko- moslavačka (Sisak; 4,140; 2.40%), Dubrovačko-neretvanska (Dubrovnik, 2,927, 2.39%), Vukovarsko-srijemska (Vukovar; 2,619; 1.46%), Karlovačka (Karlovac; 2,163; 1.68%). Muslims are largely concentrated in urban areas, most notably in the capital and the largest industrial centre Zagreb and other major towns and industrial centres in mainland Croatia: Sisak (2,442; 5.11%), Slavonski Brod (1,173; 1.98%) and Karlovac (705; 1.27%). Muslims are significantly present in ports, industrial and tourist centers of Northern Adriatic: Rijeka (5,820; 4.52%), Pula (3.275; 5.70%), Labin (1,243; 10.68%), Vodnjan (858; 14.02%), Poreč (710; 4.25%), Umag (669; 4.97%), Raša (569; 17.88%), Rovinj (507, 3.55%), Buzet (240; 3.91%) and Buje (207; 3.99%). -

Population in Croatia: According to the Census Data 1880-2011

According to the census data 1880-2011 Dr. Melita Švob, CENDO Jewish religious population in Croatia according census data Project „Jewish (religious) population in Croatia” is continuation of our previous research on Jewish population in Croatia. In proposed project we will focus on census data in which Jews has been registered with two possibilities - by nationality and by religion. • We collect and review available census data, publications and data about Jewish population in Croatia, demography, communal organization, suffering in Holocaust and migration after war. We search for numbers of Jews in communities, in list of victims and survivors, list of emigrated and immigrated persons and results of surveys • We visited Central Statistical office and other institutions and asked for edited and non edited census data about Jewish religious population. • Special attention was given to the census data after World War II, because during the communistic time question about religion was not asked or was not further elaborated. • We investigated data in 12 censuses: in years 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011. We found data about religion in censuses from years 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, 1921, 1931, 1953, 1991, 2001 and 2011. Number of Jews in Croatia according nationality and religion in censuses 1880 - 2011 Total population Jews Year In Croatia By nationality By religion 1880. 2 506 228 - 13 634 1890. 2 854 558 - 17 515 1900. 3 161 456 - 20 131 1910. 3 460 584 - 21 831 1921. 3 443 375 - 19 777 1931. 3 785 455 - 20 567 1948. 3 779 858 - - 1953. -

Slavonski Brod U Drugom Svjetskom Ratu

Slavonski Brod u Drugom svjetskom ratu Sivrić, Andrija Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:261417 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-29 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA POVIJEST SLAVONSKI BROD U DRUGOM SVJETSKOM RATU DIPLOMSKI RAD Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein Student: Andrija Sivrić Zagreb, travanj 2020. Sadržaj Uvod ............................................................................................................................. 1 1. POLITIČKE PRILIKE U GRADU UOČI RATA ................................................ 3 1.1. Izbori 1938. ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Politička previranja u novoj vlasti .................................................................... 4 1.2.1. Raspuštanje mjesne i kotarske organizacije HSS ................................... 5 2. NOVA VLAST ...................................................................................................... 11 2.1. Travanj 1941.g. .............................................................................................. 11 -

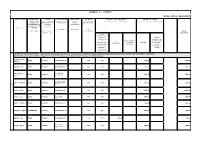

Dodatak 1 – Primjer Datum Objave:30/06/2021

Dodatak 1 – primjer Datum objave:30/06/2021 Ime i prezime Zdravstveni Država Primarna adresa Jedinstvena Donacije Troškovi u vezi Sastanaka Naknada za usluge radnik: Grad profesionanog profesionalne oznaka Zdravstvenim (čl. 24.1.A.(ii) i 24.1.B(i)) (čl. 24.1.A.(iii) i 24.1.B(ii)) osobnog ili prebivališta ili djelatnosti države organizacijam a profesionalnog sjedišta (opcionalno) prebivališta ili Primatelja (čl. 22.1.) sjedišta (čl. 23.6.) (čl. 23.6.) (čl. (čl. 23.6) (čl. 23.6. u 24.1.A.(i)) UKUPNO vezi čl. 22.) Opcionalno Iznos sponzorstva iz ugovora o Vezani sponzorstvu troškovi koji sa Putni troškovi su ugovoreni Trošak Zdravstvenom i troškovi Naknada uz naknadu u kotizacije organizacijom smještaja vezi / Trećim izvršavanja osobama (u usluga ime Zdrav. Organizacije) POJEDINAČNO OBJAVLJIVANJE IMENA – jedan red po Zdravstvenom radniku (tj. svi Prijenosi Vrijednosti tijekom godine po pojedinačnom Zdravstvenom radniku biti će zbrojeni: dostupnost pojedinačnog izvještaja treba biti osigurana na zahtjev Primatelja ili nadležnih tijela vlasti, već prema slučaju) ŽAGAR PETROVIĆ, ZAGREB Hrvatska JOSIPA SEISSLA 4 N/A N/A 1500,00 1500,00 MIRJANA Šamija, Ivan Zagreb Hrvatska Vinogradska 29 N/A N/A 2755,20 2755,20 Šarić Sučić, Ul. Josipa Osijek Hrvatska N/A N/A 6000,00 6000,00 Jelena Huttlera 4 Avenija Gojka Z r Čatić, Jasmina Zagreb Hrvatska N/A N/A 6000,00 6000,00 Šuška 6 d a r d a n v i Čavka, Mislav Zagreb Hrvatska Kišpatićeva 12 N/A N/A 10000,00 10000,00 s k t v e Badžek, Iva Zagreb Hrvatska Ilica 197 N/A N/A 5032,50 5032,50 n i Bakula, Marija Zagreb Hrvatska Kišpatićeva 12 N/A N/A 4000,00 4000,00 BARKOVIĆ, ANITA JASTREBARSKO Hrvatska KLINČASELSKA 11 N/A N/A 3000,00 3000,00 Bešlić, Iva Zagreb Hrvatska Vinogradska 29 N/A N/A 160,00 160,00 Ul. -

IZMJENE I DOPUNE GENERALNOG URBANISTIČKOG PLANA GRADA SLAVONSKOG BRODA Urbanistički Institut Hrvatske D.O.O

IZMJENE I DOPUNE GENERALNOG URBANISTIČKOG PLANA GRADA SLAVONSKOG BRODA Urbanistički institut Hrvatske d.o.o. Zagreb REPUBLIKA HRVATSKA BRODSKO-POSAVSKA ŽUPANIJA – GRAD SLAVONSKI BROD IZMJENE I DOPUNE GENERALNOG URBANISTIČKOG PLANA GRAD SLAVONSKI BROD KONAČNI PRIJEDLOG PLANA TEKSTUALNI DIO ODREDBE ZA PROVOĐENJE Zagreb, ožujak 2016. IZMJENE I DOPUNE GENERALNOG URBANISTIČKOG PLANA GRADA SLAVONSKOG BRODA Urbanistički institut Hrvatske d.o.o. Zagreb Županija: BRODSKO-POSAVSKA ŽUPANIJA Općina/grad: GRAD SLAVONSKI BROD Naziv prostornog plana: IZMJENE I DOPUNE GENERALNOG URBANISTIČKOG PLANA GRADA SLAVONSKOG BRODA – KONAČNI PRIJEDLOG PLANA Odluka o izradi Izmjena i dopuna Generalnog Odluka predstavničkog tijela o donošenju plana urbanističkog plana grada Slavonskog Broda: (službeno glasilo): Službeni vjesnik BPŽ broj 19/08 Javna rasprava (datum objave): Javni uvid održan Glas Slavonije 29. srpnja 2015. godine od: 06. kolovoz 2015. Posavska Hrvatska 31. srpnja 2015. godine do: 04. rujan 2015. Pečat tijela odgovornog za provođenje javne Odgovorna osoba za provođenje javne rasprave: rasprave: Damir Klaić, dipl.ing.građ. Suglasnost na plan prema članku 98. Zakona o prostornom uređenju i gradnji (“Narodne novine”, br. 76/07, 38/09, 55/11, 90/11 i 50/12) klasa: ur.br: datum: Pravna osoba/tijelo koje je izradilo plan: URBANISTIČKI INSTITUT HRVATSKE d.o.o. Zagreb, Frane Petrića 4 Pečat pravne osobe/tijela koje je izradilo plan: Odgovorna osoba: _________________________________ mr.sc. Ninoslav Dusper, dipl.ing.arh. Odgovorni voditelj izrade nacrta prijedloga plana: Lidija Škec, dipl.ing.arh. do veljače 2014. godine mr.sc. Ninoslav Dusper, dipl.ing.arh. od ožujka 2014. godine Stručni tim u izradi plana: Dunja Ožvatić, dipl.ing.arh. Dean Vučić, ing.geod. -

GENERAL ELECTIONS in CROATIA 4Th December 2011

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN CROATIA 4th December 2011 European Elections monitor The leftwing coalition forecast to win in the Croatian general elections on 4th December next. From Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy Around 4000 people, from 21 political parties are standing in the general elections in Croatia on 4th December next. 151 seats are available in the Sabor, the only chamber in parliament. D-7 For the first time in the country’s history the Independent Serb Democratic Party (SDSS) is putting 7 days before a list forward led by outgoing Deputy Prime Minister Slobodan Uzlac in one of the country’s ten the poll constituencies, the 9th (Zadar, Sibenik, Knin). Until now the SDSS only stood for the college of national minorities. On 2nd November President of the Republic Ivo Josipovic made a television appearance to call on his countrymen to vote in the election. “The voting slip is always democracy’s most powerful arm and it is in your hands,” he said. Likewise the Conference of Catholic Bishops wanted to motivate the electorate, “we cannot complain about our life if we give up trying to influence it,” reads their message. The official electoral campaign that will be the shortest that Croatia has ever known, started on 16th November and will end on 2nd December at midnight. Outgoing Prime Minister Jadranska Kosor, (Demo- and abuse of power. He is accused of having re- cratic Union HDZ), whose government includes ceived illegal funds (to a total of 480,000€ ) from the HDZ and the Farmers’ Party (HSS), a conser- an Austrian bank (Hypo Alpe Adria) whilst he was vative party led by Josip Frisic, is running in the Deputy Foreign Minister during the Croatian War 5th constituency (Pozega, Slavonski Brod, Vuko- (1991-1995) and of having later received a bribe var), her home territory (she was born in Pakrac), of 10 million € from the Hungarian petrol company and one of the HDZ’s strongholds.