Tmvenaty Microfilms International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Espectador Sevillano De Alberto Lista (1809).¿ Un Discurso

Pasado y Memoria. Revista de Historia Contemporánea ISSN: 1579-3311 [email protected] Universidad de Alicante España Morange, Claude El Espectador sevillano de Alberto Lista (1809). ¿Un discurso revolucionario? Pasado y Memoria. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, núm. 10, 2011, pp. 195-218 Universidad de Alicante Alicante, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=521552320009 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto El Espectador sevillano de Alberto Lista (1809). ¿Un discurso revolucionario? Alberto Lista’s El Espectador sevillano (1809). An Example of Revolutionary Discourse? Claude Morange Université de Paris III-Sorbonne Nouvelle Recibido: 18-X-2011 Aceptado: 28-III-2012 Resumen El Espectador sevillano, redactado por Alberto Lista, se publicó en Sevilla del 2 de oc- tubre de 1809 al 29 de enero de 1810. Aunque se trata de uno de los periódicos más importantes del momento, se le ha estudiado poco. Redactado en la ciudad que, por las circunstancias bélicas, había pasado a ser capital de la España libre, ofrece una ex- posición sistemática de los fundamentos de la doctrina política liberal, que se plasma- rían algunos meses después en la Constitución de Cádiz. En estas breves reflexiones, se trata de situar la publicación en el complejo e intenso debate de ideas de que fue entonces teatro Sevilla, para tratar de determinar hasta qué punto puede calificarse de revolucionario el pensamiento del Lista de 1809. -

MAHANI TEAVE Concert Pianist Educator Environmental Activist

MAHANI TEAVE concert pianist educator environmental activist ABOUT MAHANI Award-winning pianist and humanitarian Mahani Teave is a pioneering artist who bridges the creative world with education and environmental activism. The only professional classical musician on her native Easter Island, she is an important cultural ambassador to this legendary, cloistered area of Chile. Her debut album, Rapa Nui Odyssey, launched as number one on the Classical Billboard charts and received raves from critics, including BBC Music Magazine, which noted her “natural pianism” and “magnificent artistry.” Believing in the profound, healing power of music, she has performed globally, from the stages of the world’s foremost concert halls on six continents, to hospitals, schools, jails, and low-income areas. Twice distinguished as one of the 100 Women Leaders of Chile, she has performed for its five past presidents and in its Embassy, along with those in Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Japan, Ecuador, Korea, Mexico, and symbolic places including Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Chile’s Palacio de La Moneda, and Chilean Congress. Her passion for classical music, her local culture, and her Island’s environment, along with an intense commitment to high-quality music education for children, inspired Mahani to set aside her burgeoning career at the age of 30 and return to her Island to found the non-profit organization Toki Rapa Nui with Enrique Icka, creating the first School of Music and the Arts of Easter Island. A self-sustaining ecological wonder, the school offers both classical and traditional Polynesian lessons in various instruments to over 100 children. Toki Rapa Nui offers not only musical, but cultural, social and ecological support for its students and the area. -

Cuba and the Cubans Largely Concerns Us, and a Disturbpce of Those Conditions Affects Our Material Interests in Inany Ways

RAIMUNDO VBRERA AUTHOROF "MIS BUENOSTIEMPOS." " LOS ESTADOSUNIDOS." " ~MPRES~ONESDE VIAJE." BC.. kc. MEMBEROF THE BAR OF CUBA. PROVINCIAL EX-DEPUTY.MEMBER OF THE EXECUTIVECOMMI~TEE OF THE CUBANAUTONO- MIST PARTY. BC. TRANSLATED FROM THE EIGHTH SPANISH EDITION OF " CUBA Y SUS, JUECES" BY LAURA GUlTERAS REVISED AND EDITED BY LOUIS EDWARD LEVY AND COMPLETED WITH A SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX BY THE EDITOR ILLUSTRATED WITH 114 ENGRAVINGS AND A MAP PHILADELPHIA THE LEVYTYPE COMPANY ~Sgd GRAD . F 1783 .c1313 1896 COPYRIGHT 1896 THE LEVYTYPE COMPANY PHILADELPHIA -- 4Cad 40~3280g I IciYnGX o 2\\ ~\b\ TO THE MEMORY OF HER BELOVED UNCLE EUSEBIO GUITERAS THIS TRANSLATION IS DEDICATED BY HIS NIECE EDITOR'S PREFACE. At a time when the condition of Cuba and its people has been forced upon the attenti011 of the civilized8 world by another sanguinary contest between Spain and its Great Antillan colony, there is no need of an apology for the appearance of the present work. The American people, especially, have an abiding interest in Cuba, not alone as a matter of sentiment, but by reason of extensive commercial relations wit11 the island and of the important economic facts resulting from those relations; the condition of Cuba and the Cubans largely concerns us, and a disturbpce of those conditions affects our material interests in Inany ways. Since the beginning of 1895 the prolonged contention between the Cuba11 colonists and the mother country, which in the past has resulted in numerous insurrections and in a devastating civil war of ten years' duration, has again been taken out of the domain of parliamentary discussion by a resort to force. -

Paintodayspain

SPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAIN- TODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- ALLIANCE OF CIVILIZATIONS PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- 2009 DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- Spain today 2009 is an up-to-date look at the primary PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- aspects of our nation: its public institutions and political scenario, its foreign relations, the economy and a pano- 2009 DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- ramic view of Spain’s social and cultural life, accompanied by the necessary historical background information for PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- each topic addressed DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- http://www.la-moncloa.es PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- SPAIN TODAY TODAY SPAIN DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAIN- TODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- DAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYS- PAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTODAYSPAINTO- -

Estadounidenses and Gringos As Reality and Imagination in Mexican Narrative of the Late Twentieth Century

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2008 Estadounidenses and Gringos as Reality and Imagination in Mexican Narrative of the Late Twentieth Century Jessica Lynam Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Chicana/o Studies Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lynam, Jessica, "Estadounidenses and Gringos as Reality and Imagination in Mexican Narrative of the Late Twentieth Century" (2008). Dissertations. 791. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/791 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTADOUNIDENSES AND GRINGOS AS REALITY AND IMAGINATION IN MEXICAN NARRATIVE OF THE LATE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Jessica Lynam A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish Advisor: John Benson, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2008 UMI Number: 3340191 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Byron in Romantic and Post-Romantic Spain María Eugenia Perojo Arronte University of Valladolid

1 1 BYRON IN ROMANTIC AND POST-ROMANTIC SPAIN MARÍA EUGENIA PEROJO ARRONTE UNIVERSITY OF VALLADOLID The title of this paper seems to require a definition of Spanish Romanticism and post-Romanticism. What the terms Romanticism and post-Romanticism might mean in relation to Spanish literature has been a permanent debate among scholars. Spanish Romanticism as an aesthetic movement has been insistently questioned by many literary historiographers, adducing diverse and even opposed reasons and causes to support their albeit common agreement on its “failure” It is generally assumed that it flourished late and had “too short a lease”. Spanish nineteenth-century literature, poetry in particular, is fascinating because of its complexity for the literary historian, its resistance to be reduced to limits, to be encapsulated and easily digested in pill form. An overview of the debate through the voices of reputed scholars of the period may illustrate the controversy. The first usual reference when dealing with the development of Spanish Romanticism is to Edgar Allison Peers’ A History of the Romantic Movement in Spain . Peers considered that political causes are not a sufficient explanation for the “failure” of Spanish Romanticism. The problem, he argued, lay in the weakness of Romantic ideas among Spaniards. What he called the “Romantic revival” was “in the main a native development, and foreign influences upon it have often been given more than their due importance” .2 Sharing this idea of a failure of the movement, Vicente Llorens put his emphasis upon the persistence of Neoclassicism in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Thus, he began his study El romanticismo español 3 with the debate on Calderón’s drama which was initiated in 1814 between Johann Nikolas Böhl von Faber and José Joaquín de Mora. -

Internacional Editorial 3

OCTUBRE 2014 SEKINTERNACIONAL EDITORIAL 3 FAMILIA SEK 4 ESPECIAL PADRES 5 DOS GENERACIONES 9 ANTIGUOS ALUMNOS 16 INNOVACIÓN PEDAGÓGICA 21 ENTREVISTAS 23 MUNDO SEK 26 INTERSEK 27 PROGRAMAS INTERNACIONALES 33 COLEGIOS SEK 43 CHILE 44 COSTA RICA 47 EIRÍS 50 GUADALAJARA 54 GUATEMALA 58 GUAYAQUIL 61 LAS AMÉRICAS 65 LEVANTE 70 © INSTITUCIÓN INTERNACIONAL SEK LOS VALLES 73 WWW.SEK.NET PACÍFICO 76 D.L.:SG-125/2011 PARAGUAY 79 Queda prohibida la reproducción, total o parcial QUITO 81 de cualquier texto o ilustración de esta revista sin previa autorización. CENTROS EDUCATIVOS 86 FREE COPY - EJEMPLAR GRATUITO EDITORIAL “Cosechamos lo que sembramos” Sin duda, sabemos que las cosas que La serenidad, el autocontrol, la Saber aceptarnos y valorarnos lo más ocurren en nuestra mente son las que coherencia interna, la actitud positiva, objetivamente posible, sin que nuestros determinan las cosas que después son aspectos que admiramos en algunas defectos nos hagan perder la autoestima, ocurren en la realidad. personas y que deseamos para nosotros. desarrollar nuestra capacidad de soportar Pero ello, no es fruto de la casualidad, es frustraciones para poder aceptar el Por eso, los educadores debemos fruto de un trabajo y un logro personal de fracaso, nos dará la posibilidad de trabajar decididamente para el buen construcción interna que se aprende. renacer y realizar otros proyectos. funcionamiento del proceso de Y se aprende sobre todo en la familia aprendizaje. y en el colegio. Sin duda, éstos son objetivos primordiales en la educación, y en ellos trabajamos Si queremos que nuestros hijos, en un Saber aceptar nuestros errores y saber de forma decidida en SEK. -

El Espectador Sevillano De Alberto Lista (1809). ¿Un Discurso Revolucionario? Alberto Lista’S El Espectador Sevillano (1809)

El Espectador sevillano de Alberto Lista (1809). ¿Un discurso revolucionario? Alberto Lista’s El Espectador sevillano (1809). An Example of Revolutionary Discourse? Claude Morange Université de Paris III-Sorbonne Nouvelle Recibido: 18-X-2011 Aceptado: 28-III-2012 Resumen El Espectador sevillano, redactado por Alberto Lista, se publicó en Sevilla del 2 de oc- tubre de 1809 al 29 de enero de 1810. Aunque se trata de uno de los periódicos más importantes del momento, se le ha estudiado poco. Redactado en la ciudad que, por las circunstancias bélicas, había pasado a ser capital de la España libre, ofrece una ex- posición sistemática de los fundamentos de la doctrina política liberal, que se plasma- rían algunos meses después en la Constitución de Cádiz. En estas breves reflexiones, se trata de situar la publicación en el complejo e intenso debate de ideas de que fue entonces teatro Sevilla, para tratar de determinar hasta qué punto puede calificarse de revolucionario el pensamiento del Lista de 1809. Palabras clave: Prensa, Sevilla, Liberalismo, Revolución, Constitución. Abstract El Espectador sevillano is a journal that was edited by Alberto Lista between 1809 (2 October) and 1810 (29 January). It happened to be published in Seville for the town had just become the capital city of unoccupied Spain. El Espectador sevillano provides us with a systematic account of the fundaments of political liberalism as a doctrine that led to the writing of the Constitution of Cadiz a few months after the termination of the journal. However little attention has been paid to El Espectador sevillano despite it is being one of the most political influential journals at that time. -

Issue 141.Pmd

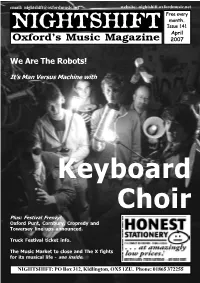

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 141 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 We Are The Robots! It’s Man Versus Machine with Keyboard Choir Plus: Festival Frenzy! Oxford Punt, Cornbury, Cropredy and Towersey line-ups announced. Truck Festival ticket info. The Music Market to close and The X fights for its musical life - see inside. NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 THIS YEAR’S TRUCK FESTIVAL will take place over the weekend of the 21st and 22nd July NEWNEWSS at Hill Farm in Steventon. Local music fans will get a chance to buy tickets ahead of the rest of Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU the country from Tuesday 10th April when Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] 1,000 tickets will go on sale at Fopp shops in Oxford and Reading as well as Dawson’s in Abingdon. More information on how to buy tickets online is available at www.truckfestival.org. No line-up details have yet been given. THE MARKET TAVERN in Market Street, home to the Music Market venue, is due to close sometime in the next two months. The pub has been bought by a Japanese restaurant chain. The exact closure date is still not certain but sometime in May looks the most likely scenario. The Music Market has become a great established live music venue over the last few years under the management of Charis Sharpe and is host to many of Delicious Music’s music nights. The Music Market is due to host the Oxford Punt on Wednesday 9th May. -

Enlightenment and Romanticism Dialectics in El Robinson Urbano’S Antonio Muñoz Molina Journalistic Articles

Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI. 2021, nº 54, 55-78 ISSN: 1576-3420 RESEARCH http://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2021.54.e632 Received: 24/02/2020 --- Accepted: 17/12/2020 --- Published: 12/04/2021 ENLIGHTENMENT AND ROMANTICISM DIALECTICS IN EL ROBINSON URBANO’S ANTONIO MUÑOZ MOLINA JOURNALISTIC ARTICLES DIALÉCTICA ILUSTRACIÓN Y ROMANTICISMO EN LOS ARTÍCULOS PERIODÍSTICOS DE EL ROBINSON URBANO, DE ANTONIO MUÑOZ MOLINA Manuel Ruiz Rico. University of Seville. Spain. [email protected] How to cite the article: Ruiz Rico, M. (2020). Enlightment and Romanticism Dialectics in El Robinson urbano’s Antonio Muñoz Molina journalistic articles. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 54, 55-78. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2021.54.e632 ABSTRACT Introduction: The Urban Robinson appeared in 1984. It was the first work published by Antonio Muñoz Molina. As such, it contains the key elements of the initial work of the author. Those elements are the foundation for his later production. Methodology: This work analyses The Urban Robinson under the dialectic between the Enlightenment and Romanticism, which offers a perspective from which to read the years and tensions of the Spanish democratic transition as a historical period, as well as the relations between journalism (exercised in freedom again) and literature. To make this analysis, this article uses a bibliography on journalism and literature, on the one hand, and, on the other, on Enlightenment and Romanticism, as well as on Postmodernism as a post-Romantic period. Discussion: The Urban Robinson is presented, in the first years of Spanish democracy, as a defense of reason and the Enlightenment project, although it also reports its risks and excesses. -

Viajeros Por América Central: Geografías, Sujetos Y

VIAJEROS POR AMÉRICA CENTRAL: GEOGRAFÍAS, SUJETOS Y CONTRADISCURSOS A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Jesús Manuel Gómez Fernández, Lic. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Maureen Ahern Dr. Lúcia Costigan Aproved by Dr. Fernando Unzueta ______________________________ Dr. Claudio González Adviser Department of Spanish and Portuguese ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the narratives of the journeys of and about four explorers who traveled across the Central American isthmus, from the 16th to early 18th centuries, when Spain ruled over these territories. It studies the travel narratives of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Juan Vásquez de Coronado, William Dampier and John Cockburn and, at the same time, it offers new perspectives on the recuperation of Central American cultural memory and heritage as it revisits and analyzes the early colonial isthmus in terms of its geographical and human landscapes. This dissertation proposes that through these “Relaciones de Viaje” the representation of the Central American Isthmus is transformed from a mythical landscape into a material one as they scrutinize the exploitable riches of the land and subject its peoples to new excluding set of rules. Rivaling the Spanish enterprise, the British search for their own truths in the Spanish territories that materialize new landscapes to non Spanish Europeans, so as to represent a counter imperialistic discourse. The isthmus thus becomes a discursive and physical battleground where the two powers clash producing new subjectivities that evolve on the margins of the Spanish project and under the protection of British Empire, as in the case of the Moskitia. -

Recovering Jewish Spain: Politics, Historiography and Institutionalization of the Jewish Past in Spain (1845-1935)

Recovering Jewish Spain: Politics, Historiography and Institutionalization of the Jewish Past in Spain (1845-1935) Michal Rose Friedman Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Michal Rose Friedman All rights reserved ABSTRACT Recovering Jewish Spain: Politics, Historiography and Institutionalization of the Jewish Past in Spain (1845-1935) Michal Rose Friedman This dissertation is a study of initiatives to recover the Jewish past and of the emergence of Sephardic Studies in Spain from 1845 to 1935. It explores the ways the Jewish past became central to efforts to construct and claim a Spanish patria, through its appropriation and integration into the nation’s official national historical narrative, or historia patria. The construction of this history was highly contentious, as historians and politicians brought Spain’s Jewish past to bear in debates over political reform, in discussions of religious and national identity, and in elaborating diverse political and cultural movements. Moreover, it demonstrates how the recovery of the Jewish past connected—via a Spanish variant of the so-called “Jewish question”—to nationalist political and cultural movements such as Neo-Catholicism, Orientalism, Regenerationism, Hispanism, and Fascism. In all of these contexts, attempts to reclaim Spain’s Jewish past—however impassioned, and however committed—remained fractured and ambivalent, making such efforts to “recover” Spain’s