Music with Context: Audiovisual Scores For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World

1 Chapter Seven Cold Commodities: Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World Haftor Medbøe Since gaining prominence in public consciousness as a distinct genre in early 20th Century USA, jazz has become a music of global reach (Atkins, 2003). Coinciding with emerging mass dissemination technologies of the period, jazz spread throughout Europe and beyond via gramophone recordings, radio broadcasts and the Hollywood film industry. America’s involvement in the two World Wars, and the subsequent $13 billion Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe as a unified, and US friendly, trading zone further reinforced the proliferation of the new genre (McGregor, 2016; Paterson et al., 2013). The imposition of US trade and cultural products posed formidable challenges to the European identities, rooted as they were in 18th-Century national romanticism. Commercialised cultural representations of the ‘American dream’ captured the imaginations of Europe’s youth and represented a welcome antidote to post-war austerity. This chapter seeks to problematise the historiography and contemporary representations of jazz in the Nordic region, with particular focus on the production and reception of jazz from Norway. Accepted histories of jazz in Europe point to a period of adulatory imitation of American masters, leading to one of cultural awakening in which jazz was reimagined through a localised lens, and given a ‘national voice’. Evidence of this process of acculturation and reimagining is arguably nowhere more evident than in the canon of what has come to be received as the Nordic tone. In the early 1970s, a group of Norwegian musicians, including saxophonist Jan Garbarek (b.1947), guitarist Terje Rypdal (b.1947), bassist Arild Andersen (b.1945), drummer Jon Christensen (b.1943) and others, abstracted more literal jazz inflected reinterpretations of Scandinavian folk songs by Nordic forebears including pianist Jan Johansson (1931-1968), saxophonist Lars Gullin (1928-1976) bassist Georg Riedel (b.1934) (McEachrane 2014, pp. -

Programme 2009 the Abel Prize Ceremony 19 May 2009 Procession Accompanied by the “Abel Fanfare” Music: Klaus Sandvik

Programme 2009 The Abel Prize Ceremony 19 May 2009 Procession accompanied by the “Abel Fanfare” Music: Klaus Sandvik. Performed by three musicians from the Staff Band of the Norwegian Defence Forces Their Majesties King Harald and Queen Sonja enter the hall Soroban Arve Henriksen (trumpet) (Music: Arve Henriksen) Opening by Øyvind Østerud President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Eg veit i himmerik ei borg Trio Mediæval, Arve Henriksen (Norwegian folk tune from Hallingdal, arr. Linn A. Fuglseth) The Abel Prize Award Ceremony Professor Kristian Seip Chairman of the Abel Committee The Committee’s citation His Majesty King Harald presents the Abel Prize to Mikhail Leonidovich Gromov Acceptance speech by Mikhail Leonidovich Gromov Closing remarks by Professor Øyvind Østerud President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Till, till Tove Trio Mediæval, Arve Henriksen, Birger Mistereggen (percussion) (Norwegian folk tune from Vestfold, arr. Tone Krohn) Their Majesties King Harald and Queen Sonja leave the hall Procession leaves the hall Other guests leave the hall when the procession has left to a skilled mathematics teacher in the upper secondary school is called after Abel’s own Professor Øyvind Østerud teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboe. There is every reason to remember Holmboe, who was President of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Abel’s mathematics teacher at Christiania Cathedral School from when Abel was 16. Holmboe discovered Abel’s talent, inspired him, encouraged him, and took the young pupil considerably further than the curriculum demanded. He pointed him to the professional literature, helped Your Majesties, Excellencies, dear friends, him with overseas contacts and stipends and became a lifelong colleague and friend. -

Arve Henriksen Cartography

ECM Arve Henriksen Cartography Arve Henriksen: trumpets, voice, field recordings. With Jan Bang: live sampling, beats, dictaphone, programming; Audun Kleive; percussion; David Sylvian: voice, samples, programming; Helge Sunde: string arrangements, programming; Eivind Aarset: guitars; Lars Danielsson: double-bass, Erik Honoré: synthesizer, samples; Arnaud Mercier: treatments; Trio Mediaeval: voice sample; Vérène Andronikof: vocals; Vytas Sonndeckis: vocal arrangement (collective personnel) ECM 2086 6025 178 0116 (5) Release: October 2008 The uniquely lyrical, liquid and mellifluous sound of Arve Henriksen’s trumpet has had an important supportive role to play on a number of ECM recordings of the last decade. Amongst them – Christian Wallumrød’s “No Birch”, “Sofienberg Variations”, “A Year from Easter” and “The Zoo is Far”, Trygve Seim’s “Different Rivers”, “The Source and Different Cikadas” and “Sangam” , Jon Balke’s “Kyanos”, Sinikka Langeland’s “Starflowers”, Frode Haltli’s “Passing Images”, Arild Andersen’s “Elektra” ... albums which between them represent a very broad range of musical possibilities. In each context, however, Henriksen has proven to be both a highly-distinctive and uncommonly adaptive player. This versatility provides a subtext for the present disc, which pools a shifting cast of creative musicians from diverse genres including jazz, electronica, ambient and classical music and the world of the remix. Ex-pop singer David Sylvian makes two appearances reading his own texts, Ana Maria Friman sings fragments of William Brooks’s “Anima Mea” and the voices of the Trio Mediaeval emerge, sampled, on “recording Angel”. Guitarist Eivind Aarset, and drummer Audun Kleive loom out of the mix, and Ståle Storløkken, Arve’s colleague from noise/rock/improv band Supersilent, has a cameo on “Famine’s Ghost”. -

PDF Transition

! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:” ! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN PERICH! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation! Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School! of Cornell University! in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of! Doctor of Musical! Arts! ! ! by! David Benjamin Friend! May 2019! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © 2019 David Benjamin! Friend! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:”! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN! PERICH! ! David Benjamin Friend, D.M.A.! Cornell University,! 2019! ! !This dissertation examines the life and work of Tristan Perich, with a focus on his works for keyboard instruments. Developing an understanding of his creative practices and a familiarity with his aesthetic entails both a review of his personal narrative as well as its intersection with relevant musical, cultural, technological, and generational discourses. This study examines relevant groupings in music, art, and technology articulated to Perich and his body of work including dorkbot and the New Music Community, a term established to describe the generationally-inflected structural shifts! in the field of contemporary music that emerged in New York City in the first several years of the twenty-first century. Perich’s one-bit electronics practice is explored, and its impact on his musical and artistic work is traced across multiple disciplines and a number of aesthetic, theoretical, and technical parameters. This dissertation also substantiates the centrality of the piano to Perich’s compositional process and to his broader aesthetic cosmology. A selection of his works for keyboard instruments are analyzed, and his unique approach to keyboard technique is contextualized in relation to traditional Minimalist piano techniques and his one-bit electronics practice." ! ! BIOGRAPHICAL! SKETCH! ! !! !David Friend (b. -

Live Performance

LIVE PERFORMANCE LIVE PERFORMANCE AND MIDI Introduction Question: How do you perform electronic music without tape? Answer: Take away the tape. Since a great deal of early electroacoustic music was created in radio stations and since radio stations used tape recordings in broadcast, it seemed natural for electroacoustic music to have its final results on tape as well. But music, unlike radio, is traditionally presented to audiences in live performance. The ritual of performance was something that early practitioners of EA did not wish to forsake, but they also quickly realized that sitting in a darkened hall with only inanimate loudspeakers on stage would be an unsatisfactory concert experience for any audience. HISTORY The Italian composer Bruno Maderna, who later established the Milan electronic music studio with Luciano Berio, saw this limitation almost immediately, and in 1952, he created a work in the Stockhausen's Cologne studio for tape and performer. “Musica su Due Dimensioni” was, in Maderna’s words, “the first attempt to combine the past possibilities of mechanical instrumental music with the new possibilities of electronic tone generation.” Since that time, there have been vast numbers of EA works created using this same model of performer and tape. On the one hand, such works do give the audience a visual focal point and bring performance into the realm of electroacoustic music. However, the relationship between the two media is inflexible; unlike a duet between two instrumental performers, which involves complex musical compromises, the tape continues with its fixed material, regardless of the live performer’s actions. 50s + 60s 1950s and 60s Karlheinz Stockhausen was somewhat unique in the world of electroacoustic music, because he was not only a pioneering composer of EA but also a leading acoustic composer. -

Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival on Nature

ultima oslo contemporary 10–19 september 2015 ultima music festival oslo contemporary music festival om natur 10.–19. september 2015 10.–19. on nature 1 programme THURSDAY 10 SEPTEMBER Lunchtime concert Henrik Hellstenius Ørets teater III: Ultima Academy Cecilie Ore Ultima Academy Eivind Buene Georg Friedrich Haas In Vain SATURDAY 19 SEPTEMBER Herman Vogt Om naturen (WP) Alexander Schubert in conversation Adam & Eve—A Divine Comedy Geologist Henrik H. Svensen The Norwegian Chamber Orchestra Ensemble Ernst Ultima Remake Concordia Discors, Études (WP) Oslo Sinfonietta / Dans les Arbres with rob Young 21:00 — Kulturkirken Jakob on issues in the Age of Man 19:00 — Universitetets aula 21:00 — Riksscenen Edvin Østergaard (WP) / 10:00 — Edvard Munch Secondary 12:00 — Loftet 19:30 — The Norwegian National Opera 14:00 — Kulturhuset p. 18 19:30 — Kulturhuset New music by Eivind Buene, plus the Spellbinding piece described as ‘an optical Jan Erik Mikalsen (WP) / Maja Linderoth School Piano studies with Ian Pace, piano & Ballet, (Also 12 and 13 September) p. 31 p. 35 pieces that inspired it illusion for the ear’” The Norwegian Soloists’ Choir Interactive installation created by pupils p. 19 Concert / performance Robert Ashley Perfect Lives p. 38 p. 47 13:00 — Universitetets gamle festsal p. 13 p. 16 Ultima Academy Matmos Ultima Academy p. 53 Installation opening and concert Music Professor Rolf Inge Godøy 22:00 — Vulkan Arena Musicologist Richard Taruskin on David Toop Of Leonardo da Vinci — James Hoff / Afrikan Sciences / Ultima Academy Elin Mar Øyen Vister Røster III (WP) Installation opening on sound and gesture American electronica duo perform cele- birdsong, music and the supernatural Quills / a Black Giant / Deluge (WP) Hilde Holsen Øyvind Torvund (WP) / Jon Øivind Media theorist Wolfgang Ernst 15:00 — Deichmanske Ali Paranadian Untitled I, 14:30 — Kulturhuset brated TV opera 20:30 — Kulturhuset Elaine Mitchener / David Toop 22:00 — Blå Ness (WP) / Iannis Xenakis on online culture and hovedbibliotek A Poem for Norway (WP) p. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Discographie

Discographie I. Précurseurs musiques savantes Compilations An Anthology Of Noise & Electronic Music, Vol. 1-5 (Sub Rosa, 2000-2007) Le bruit dans la musique 1900-1950 Compilations Dada et la musique (Centre Georges Pompidou/A&T, 2005) Futurism & Dada Reviewed 1912-1959, (Sub rosa, 1995) Musica Futurista : The Art Of Noise (LTM, 2005) George Antheil, Ballet mécanique, dirigé par Daniel Spalding (Naxos, 2001) Belà Bartók, Le mandarin merveilleux, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1997) John Cage, Sonatas And Interludes For Prepared Piano, interprété par Boris Berman (Naxos, 1999) John Cage, Imaginary Landscapes, dirigé par Jan Williams (Hat Hut, 1995) Henry Cowell, New Music : Piano Compositions By Henry Cowell, interprété par Sorrel Hays, Joseph Kubera, Sarah Cahill (New Albion Records, 1999) Charles Ives, Symphony n°2 etc., dirigé par Léonard Bernstein (Deutsche Grammophon, 1990) Erik Satie, Parade, dirigé par Manuel Rosenthal (Ades, 2007) Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot lunaire, Lied der Waldtaube, Erwartung dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Sony, 1993) Edgard Varese, The Complete Works, dirigé par Riccardo Chailly (Decca, 1998) Musique et timbre, 1950 à nos jours Luciano Berio, Differences, Sequenzas III & VII, Due pezzi, Chamber Music (Lilith, 2007) György Ligeti, Requiem, Aventures, Nouvelles Aventures (Wergo, 1985) György Ligeti, Chamber Concerto, Ramifications, String Quartet n°2, Aventures, Lux aeterna, dirigé par Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1983) Tristan Murail, Gondwana, Désintégrations, Time and Again (Disques Montaigne, 2003) Giacinto Scelsi, The Orchestral Works 2 (Mode, 2006) Krzysztof Penderecki, Anaklasis, Threnody, etc., dirigé par Wanda Wilkomirska (EMI, 1994) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Aus den sieben Tagen (Harmonia Mundi, 1988) Karlheinz Stockhausen, Stimmung (Hyperion, 1986) Iannis Xenakis, Orchestral Works, Vol. -

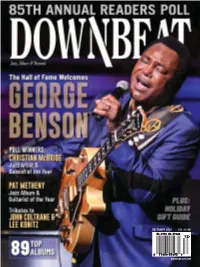

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION of the EARLY ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZER Author(S): Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco Source: Icon, Vol

International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC) THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE EARLY ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZER Author(s): Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco Source: Icon, Vol. 4 (1998), pp. 9-31 Published by: International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23785956 Accessed: 27-01-2018 00:41 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Icon This content downloaded from 70.67.225.215 on Sat, 27 Jan 2018 00:41:54 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE EARLY ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZER Trevor Pinch and Frank Troceo In this paper we examine the sociological history of the Moog and Buchla music synthesizers. These electronic instruments were developed in the mid-1960s. We demonstrate how relevant social groups exerted influence on the configuration of synthesizer construction. In the beginning, the synthesizer was a piece of technology that could be designed in a variety of ways. Despite this interpretative flexibility in its design, it stabilised as a keyboard instrument. -

Dossier Pédagogique Musiques Électroniques

Les musiques électroniques Médiathèque de Magny le Hongre - Saison culturelle 2012-2013 En collaboration avec la scène de musiques actuelles File 7 REMERCIEMENTS 3 LA BANDE SON DU DOSSIER 4 PREFACE 5 LA CONQUETE DE L’ELECTRIQUE : REPERES HISTORIQUES 7 UNE RECHERCHE INSTRUMENTALE DE LONGUE HALEINE 7 L’ELECTROACOUSTIQUE : LA MUSIQUE CONTEMPORAINE INVENTE L’ELECTRO 8 MUSIQUES ELECTRONIQUES, UN TERME PLURIEL 12 FAMILLE DOWNTEMPO : L’ELECTRO EN MODE APAISE 12 AMBIENT (784.21) 12 TRIP HOP (784.22) 13 ABSTRACT HIP HOP (784.22) 14 ELECTRO DUB (784.23) 15 ELECTRO JAZZ (784.53) 16 FAMILLE CLUB : LE CŒUR DU MOUVEMENT 17 HOUSE MUSIC (FAMILLE 784.3) 17 TECHNO (784.41) 18 MINIMAL (784.33 – 784.41 – ETC .) 19 TRANCE (784.42) 20 HARDCORE – HARDTEK (784.43) 21 DANCE MUSIC (784.8) 22 FAMILLE BREAKBEAT : SYNCOPE SUR LE DANCEFLOOR 22 JUNGLE – DRUM’N’BASS (784.7) 22 BIG BEAT (784.51) 24 DUBSTEP (784.34) 25 FAMILLE EXPERIMENTALE : RECHERCHE ET INNOVATION 26 ELECTRONICA – IDM (FAMILLE 784.6) 26 NOUVELLES PRATIQUES ET RENOUVEAU IDENTITAIRE 28 LAISSEZ NOUS RAVER ! LES NOUVEAUX NOMADES 28 LES DJ : RETOUR VERS UN MUSICIEN EN DEVENIR 30 BIBLIOGRAPHIE 34 OUVRAGES EN LIGNE 34 2 Réseau des Médiathèques du SAN du Val d’Europe Remerciements La partie « Musiques électroniques, un terme pluriel » utilise principalement les textes réalisés par Pascal Acoulon, Janick Tual, Nadège Vauclin de la médiathèque de Noisy-le-Sec. Merci à eux pour l’aimaBle autorisation d’utilisation de leur production. Merci à Cedric Heurteux et aux discothécaires de la médiathèque Gérard Billy de Lagny sur Marne. -

Nycemf 2021 Program Book

NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ VIRTUAL ONLINE FESTIVAL __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 3 STEERING COMMITTEE 3 REVIEWING 6 PAPERS 7 WORKSHOPS 9 CONCERTS 10 INSTALLATIONS 51 BIOGRAPHIES 53 DIRECTOR’S NYCEMF 2021 WELCOME STEERING COMMITTEE Welcome to NYCEMF 2021. After a year of having Ioannis Andriotis, composer and audio engineer. virtually all live music in New York City and elsewhere https://www.andriotismusic.com/ completely shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic, we decided that we still wanted to provide an outlet to all Angelo Bello, composer. https://angelobello.net the composers who have continued to write music during this time. That is why we decided to plan another virtual Nathan Bowen, composer, Professor at Moorpark electroacoustic music festival for this year. Last year, College (http://nb23.com/blog/) after having planned a live festival, we had to cancel it and put on everything virtually; this year, we planned to George Brunner, composer, Director of Music go virtual from the start. We hope to be able to resume Technology, Brooklyn College C.U.N.Y. our live concerts in 2022. Daniel Fine, composer, New York City The limitations of a virtual festival meant that we could plan only to do events that could be done through the Travis Garrison, composer, Music Technology faculty at internet. Only stereo music could be played, and only the University of Central Missouri online installations could work. Paper sessions and (http://www.travisgarrison.com) workshops could be done through applications like zoom. We hope to be able to do all of these things in Doug Geers, composer, Professor of Music at Brooklyn person next year, and to resume concerts in full surround College sound.