The Season of Septuagesima, and Vigils and Octaves, in the Extraordinary Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Second Sunday After Pentecost

Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church and School Quinquagesima Saturday, March 2, 2019 Sunday, March 3, 2019 Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church and School Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod 4206 West Elm Street • McHenry, IL 60050 (815) 385-0859 • [email protected] www.zionmchenry.org Rev. Mark Buetow Rev. Aden Loest Pastor & School Director Pastor Emeritus (618) 318-3680 (815) 385-0859 [email protected] [email protected] Thank you for worshiping with us at Zion. As you hear God’s Word, we pray that you would find peace and strength in our Lord, Jesus Christ. PRE-LENT is the season in which the Church begins to prepare for the Lenten Fast. It is the pre- game or warm up for Lent. Time to start thinking repentance and faith! Time to work out turning your eyes from you and putting them on Jesus! Time to start the countdown for Easter! PreLent is the season of the "Gesima” Sundays where the Church begins to count the days until Easter. Septuagesima means "70th." Sexagesima means "60th.” Quinquagesima means "50th." Each Sunday gives us a rough estimate of how many days we have until Easter. Happy Pre-Lent! Start getting ready, Lent is almost here! Communion Policy In the Lord's Supper, our Lord Jesus Christ gives to us His Body to eat and His Blood to drink for the remission of our sins (Matt. 26:26-28, Mark 14:22-24, Luke 22:19-2). Our Lord invites to His table those who trust His words and repent of all sins. Because Holy Communion is a proclamation and confession of the Faith which is confessed at this altar (1 Cor. -

Laissez Les Bons Temps Rouler

Laissez les bons temps rouler. AT SAINT MARTIN DE PORES ANOTHER CHAPTER IN OUR CATHOLIC FAMILY’S STORY Septuagesima Sunday Traditionally it kicks off a season known by various names throughout the world; Carnival and Shrovetide This has been a part of our Catholic culture for centuries! Carnival The word carnival comes from the Latin carnelevarium which means the removal of meat or farewell to the flesh. This period of celebration has its origin in the need to consume all remaining meat and animal products, such as eggs, cream and butter, before the six- week Lenten fast. Since controlled refrigeration was uncommon until the 1800s, the foods forbidden by the Church at that time would spoil. Rather than wasting them, families consumed what they had and helped others do the same in a festive atmosphere. Carnival celebrations in Venice, Italy, began in the 14th century. Revelers would don masks to hide their social class, making it difficult to differentiate between nobles and commoners. Today, participants wear intricately decorated masks and lavish costumes often representing allegorical characters while street musicians entertain the crowds. But arguably, the most renowned Carnival celebrations take place in Brazil. In the mid 17th century, Rio de Janeiro’s middle class adopted the European practice of holding balls and masquerade parties before Lent. The celebrations soon took on African and Native American influence, yielding what today is the most famous holiday in Brazil. Carnival ends on Mardi Gras, which is French for Fat Tuesday—the last opportunity to consume foods containing animal fat before the rigors of Lent’s fast begin. -

Septuagesima

Septuagesima The Sunday of the Vineyard “For the kingdom of heaven is like a master of a house who went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard.” Matthew 20:1 Septuagesima 31 January A+D 2021 Welcome in Jesus’ name to our guests this holy day. We pray God’s richest blessings to you as we hear His Word and receive His gifts. Please sign our guestbook in the narthex. Worship at St. Paul’s is conducted according to the historic, liturgical worship patterns of the Christian Church throughout the ages. The rhythm of worship is from our God to us, and then from us back to Him. He gives His gifts, and together we receive and extol them. The Lord’s Supper is offered every Sunday of the month. St. Paul’s observes the biblical practice of close communion. Members of sister congregations of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod are encouraged to commune with us. We ask visitors who are not members of the LC-MS to speak with one of our pastors if you are interested in learning more about our church and communion practices. Septuagesima: The Sunday of the vineyard “The Lord’s Call from Presumption to Repentance” Grace Alone The people of Israel contended with the Lord in the wilderness (Ex. 17:1–7). They were dissatisfied with His provision. In the same way, the first laborers in the vineyard complained against the landowner for the wage he provided them (Matt. 20:1–16). They charged him with being unfair, but in reality, he was being generous. -

Sagrado Corazón De Jesús, En

Nº 647/25-VI-2009 SEMANARIO CATÓLICO DE INFORMACIÓN EDIC. NACIONAL ¡Sagrado¡Sagrado¡Sagrado CorazónCorazónCorazón dedede Jesús,Jesús,Jesús, enenen VosVosVos confío!confío!confío! A SUMARIO Ω Etapa II - Número 647 3-5/13 ...y además Edición Nacional 6 La foto Consagración de España Edita: 7 Criterios al Sagrado Corazón de Jesús: Fundación San Agustín. Mundo Cristo puede renovarnos. 10 Comienza el Año Sacerdotal: Arzobispado de Madrid Va a haber mucho fruto. El sacerdote es indispensable. Delegado episcopal: Homilía del cardenal Alfonso Simón Muñoz 11 Tras las huellas de san Pío arzobispo de Madrid Redacción: de Pietrelcina Calle de la Pasa, 3. 28005 Madrid. Aquí y ahora Téls: 913651813/913667864 12 JMJ 2011: Fax: 913651188 Oración, Evangelio y fútbol. Dirección de Internet: 14 Testimonio http://www.alfayomega.es 8-9/26 E-Mail: 15 El Día del Señor [email protected] 16-17 Raíces Clausura Director: Campaña Dibujos por la vida: Miguel Ángel Velasco Puente del Año Paulino: Los niños nos enseñan Redactor Jefe: Un año que ha dado Ricardo Benjumea de la Vega qué es la vida un nuevo empuje Director de Arte: 22-23 La vida Francisco Flores Domínguez a la Iglesia. Desde la fe Redactores: Siria: Tras las huellas Anabel Llamas Palacios (Jefe de sección) de san Pablo 24 Congreso en Granada: Juan Luis Vázquez Díaz-Mayordomo, Una reflexión sobre la razón María Martínez López, y la ideología. José Antonio Méndez Pérez, 25 Don Javier Prades, Jesús Colina Díez (Roma) 18-21 Secretaría de Redacción: nuevo Decano de San Dámaso: Cati Roa Gómez Documento La fe ensancha la razón. -

The Mass As the Liturgical Calendar and Computus

Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online, Vol. 13, 2015-16 Irène Guletsky - The Mass as the Liturgical Calendar and Computus The Mass as the Liturgical Calendar and Computus IRÈNE GULETSKY During the second half of the 1990s, I had the good fortune to work on my doctoral thesis at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem under the supervision of two amazing scholars, professors Judith Cohen and Dalia Cohen (of blessed memory).1 I remember with pleasure this time spent in intensely creative work, our meetings, fascinating discussions, and occasional heated debates on various issues to do with the philosophical and theoretical views of the Renaissance, the form of the Mass and methods of its analysis. Our opinions did not always coincide—a consequence of different schools and scientific traditions. Judith was a disciple of Kurt von Fischer, and she, like her mentor, regarded the Mass primarily from the standpoint of the embodiment of the original source and the features of the counterpoint (a completely justified view).2 This strictly academic approach favored by Judith, accounted for her rather cautious, even skeptical attitude to my ideas of analyzing the cycle form as a kind of structure and a crystal, which characterize this genre as a whole. Admittedly, Judith had sufficiently valid reasons for being skeptical. After all, it is a known fact that the Mass—the five-part Ordinary—was not performed as a single separate composition, but had been distributed through the liturgy, and thus, as many scholars would have it, could hardly be defined as a form.3 Judith would bring the flight of my ideas firmly back to earth, dampening my fervor by demanding proof for every assertion, making me perform meticulous work on the text and bibliography. -

Diploma Arbeit Lijo

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Placid Podipara´s Reflection on the Church “St. Thomas Christians are Indian in Culture” Verfasser Lijo Joseph angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Theologie (Mag. theol.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 011 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Katholische Fachtheologie Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Rudolf Prokschi 2 Dedicated to all the members of the Syro-Malabar Church 3 4 Acknowledgements This is a master’s degree thesis investigate on Placid Podipara’s reflection on the Church “St. Thomas Christians are Indian in culture”. It is a humble attempt to know how Fr. Placid Podipara understood the birth and spread of Christianity through the preaching of St. Thomas the Apostle. With the passage of time, Christian religion rooted well, adapting itself to the customs and practices of the place. There was no attempt on the part of Christians to remain aloof from a given society or tried to remain a separate entity. The Church has accepted, absorbed, and assimilated itself to the good elements of Indian culture. With deep sense of gratitude, I acknowledge the valuable contribution of some important persons who helped me to complete this task. I am thankful to my bishop, Mar Mathew Arackal, Bishop of Kanjirappally, India, who sent me to Austria to do my theological studies in the University of Vienna. Gratefully I acknowledge the role of Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Rudolf Prokschi for his valuable suggestions, corrections, and guidance. I thank Fr. Stephan Mararikulam MSFS, Fr. Joy Plathottathil SVD, Stefan Jahns, Dr. Daniel Galadza, and Michaela Zachs for the correction of the language and suggestions. -

Pfingsten I Pentecost

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL Feie1iag PFINGSTEN I PENTECOST Pentecost is also the Greek name for Jewish Feast of Weeks (Shavuot), falling on the 50th day of Passover. It was during the Feast of Weeks that the first fruits of the grain harvest were presented (see Deuteronomy 16:9). New Testament references to Pentecost likely refer to the Jewish feast and not the Christian feast, which gradually developed during and after the Apostolic period. In the English speaking countries, Pentecost is also known as Whitsunday. The origin of this name is unclear, but may derive from the Old English word for "White Sunday," referring to the practice of baptizing converts clothed in white robes on the Sunday of Pentecost. In the English tradition, new converts were baptized on Easter, Pentecost, and All Saints Day, primarily for pragmatic purposes: people went to church these days. Alternatively, the name Whitsunday may have originally meant "Wisdom Sunday," since the Holy Spirit is traditionally viewed as the Wisdom of God, who bestows wisdom upon Christians at baptism. Pentecost (Ancient Greek: IlcvrrtKO<>Til [i\µtpa], Liturgical year Pentekoste [hemera}, "the fiftieth [day]") is the Greek Western name for the Feast of Weeks, a prominent feast in the calendar of ancient Israel celebrating the giving of the Law on Sinai. This feast is still celebrated in Judaism as • Advent Shavuot. Later, in the Christian liturgical year, it became • Christmastide a feast commemorating the descent of the Holy Spirit • Epiphanytide upon the Apostles and other followers of Jesus Christ • Ordinary Time (120 in all), as described in the Acts of the Apostles 2:1- • Septuagesima/Pre-Lent/Shrovetide 31. -

2021-02-14 Quinquagesima Sunday

— www.icksp.org/waterbury-home — www.facebook.com/StPatrickParishandOratory/ QUINQUAGESIMA SUNDAY FEBRUARY 14, AD 2021 LET US BEGIN LENT ! LENTEN REGULATIONS TO OBSERVE The command to do penance was uttered by Jesus Christ in no uncertain terms: “Unless you do 1. Ash Wednesday (February 17, AD 2021) and penance, you shall all likewise perish,” (Luke 13: 3- Good Friday (April 2, AD 2021) are days of 5). After Christ’s resurrection we again find in Luke COMPLETE ABSTINENCE FROM MEAT; AND 24: 46-47, “It behooved Christ to suffer and to rise ARE ALSO DAYS OF FAST, that is, only one full again from the dead the third day: that penance meal is allowed; with no eating between meals. and remission of sins should be preached in His Two other meals, sufficient to maintain Name.” strength, may be taken according to one’s While the external circumstances of penance needs but they together should not equal that have changed in this modern age, the burden of fasting of the full meal. having been lightened and dispensations multiplied to 2. The other Fridays of Lent are days of fit the less physically strong but more hurried and strained modern-day lifestyle, we are still called by our abstinence from meat. Master to deny ourselves and take up the Cross to 3. The obligation to abstain from meat binds on follow Him, praying with Him in the desert. all who have reached the age of 14. The materialistic notion that many have of 4. The obligation to fast binds all between the penance often leads to its entire neglect or unworthy ages of 18 and 59. -

South-Pacific-Script.Pdf

RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN'S SOUTH PACIFIC First Perfol'mance at the 1vlajestic Theatre, New York, A pril 7th, 1949 First Performance in London, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, November 1st, 1951 THE CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) NGANA JEROME HENRY ENSIGN NELLIE FORBUSH EMILE de BECQUE BLOODY MARY BLOODY MARY'S ASSISTANT ABNER STEWPOT LUTHER BILLIS PROFESSOR LT. JOSEPH CABLE, U.S.M.C. CAPT. GEORGE BRACKETT, U.S.N. COMMDR. WILLIAM HARBISON, U.S.N. YEOMAN HERBERT QUALE SGT. KENNETH JOHNSON SEABEE RICHARD WEST SEABEE MORTON WISE SEAMAN TOM O'BRIEN RADIO OPERATOR, BOB McCAFFREY MARINE CPL. HAMILTON STEEVES STAFF-SGT. THOMAS HASSINGER PTE. VICTOR JEROME PTE. SVEN LARSEN SGT. JACK WATERS LT. GENEVIEVE MARSHALL ENSIGN LISA MANELLI ENSIGN CONNIE WALEWSKA ENSIGN JANET McGREGOR ENSIGN BESSIE NOONAN ENSIGN PAMELA WHITMORE ENSIGN RITA ADAMS ENSIGN SUE YAEGER ENSIGN BETTY PITT ENSIGN CORA MacRAE ENSIGN DINAH MURPHY LIAT MARCEL (Henry's Assistant) LT. BUZZ ADAMS Islanders, Sailors, Marines, Officers The action of the play takes place on two islands in the South Pacific durin~ the recent war. There is a week's lapse of time between the two Acts. " SCENE I SOUTH PACIFIC ACT I To op~n.o House Tabs down. No.1 Tabs closed. Blackout Cloth down. Ring 1st Bar Bell, and ring orchestra in five minutes before rise. B~ll Ring 2nd Bar three minutes before rise. HENRY. A Ring 3rd Bar Bell and MUSICAL DIRECTOR to go down om minute before rise. NGANA. N Cue (A) Verbal: At start of overt14re, Music No.1: House Lights check to half. -

Quinquagesima Sunday; Feast of St

LITURGIES FOR THE WEEK ALL MASSES ARE AVAILABLE ONLINE Sunday, February 14, 2021 –Quinquagesima Sunday; Feast of St. Valentine – Patron Saint of our Parish 9:30 AM – Holy Mass (EN/PL) (live on YouTube & Facebook) In case you don’t want to be recorded or visible (you or your minor children) For All Parishioners, Living and Deceased while attending the Mass, please take a seat in the back of the church and receive 4:00 PM – Vespers (PL) the Holy Communion only spiritually. We apologize for the inconvenience. Monday, February 15, 2021 – Weekday Tuesday, February 16, 2021 – Weekday FAITH SHARING Wednesday, February 17, 2021 – Weekday Like an ardent and faithful lover, God woos us and speaks to our hearts. Jesus 7:00 PM – Holy Mass with the distribution of the Ashes (EN/PL) (live on proclaims that he is the bridegroom of the new covenant. YouTube & Facebook) I the first reading God calls Israel back to the innocence of their Exodus Thursday, February 18, 2021 – Lenten Weekday relationship. Like a lover, God calls Israel back to be healed and made righteous. Friday, February 19, 2021 – Lenten Weekday In the second reading Paul says that he needs no letter of recommendation other 7:00 PM – Stations of the Cross (EN) (live on YouTube & Facebook) than the faithful community at Corinth. God's own Spirit wrote the message of Saturday, February 20, 2021 – Lenten Weekday salvation in their hearts. Sunday, February 21, 2021 – 1 Sunday of Lent In the Gospel passage for today Jesus is the bridegroom, the sign of the marriage 9:30 AM – Holy Mass (EN/PL) (live on YouTube & Facebook) covenant between God and his people. -

Calendar of the Christian Year

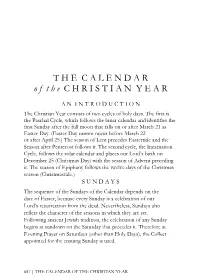

T H E C A L E N D A R o f t h e C H R I S T I A N Y E A R A N I N T R O D U C T I O N The Christian Year consists of two cycles of holy days. The first is the Paschal Cycle, which follows the lunar calendar and identifies the first Sunday after the full moon that falls on or after March 21 as Easter Day. (Easter Day cannot occur before March 22 or after April 25.) The season of Lent precedes Eastertide and the Season after Pentecost follows it. The second cycle, the Incarnation Cycle, follows the solar calendar and places our Lord’s birth on December 25 (Christmas Day) with the season of Advent preceding it. The season of Epiphany follows the twelve days of the Christmas season (Christmastide.) S U N D A Y S The sequence of the Sundays of the Calendar depends on the date of Easter, because every Sunday is a celebration of our Lord’s resurrection from the dead. Nevertheless, Sundays also reflect the character of the seasons in which they are set. Following ancient Jewish tradition, the celebration of any Sunday begins at sundown on the Saturday that precedes it. Therefore at Evening Prayer on Saturdays (other than Holy Days), the Collect appointed for the ensuing Sunday is used. 687 | THE CALENDAR OF THE CHRISTIAN YEAR P R I N C I P A L F E A S T S Easter Day Christmas Day December 25 Ascension Day The Epiphany January 6 The Day of Pentecost All Saints’ Day November 1 Trinity Sunday These feasts take precedence over any other day or observance. -

A Table of the Moveable Feasts for Twenty Years (2021-2040)

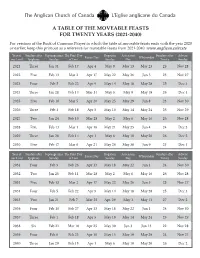

A TABLE OF THE MOVEABLE FEASTS FOR TWENTY YEARS (2021-2040) For versions of the Book of Common Prayer in which the table of moveable feasts ends with the year 2020 or earlier, keep this printout as a reference for moveable feasts from 2021-2040. www.anglican.ca/texts Year of Sundays after Septuagesima The First Day Rogation Ascension Sundays after Advent Easter Day Whitsunday our Lord Epiphany Sunday of Lent Sunday Day Trinity Sunday 2021 Three Jan 31 Feb 17 Apr 4 May 9 May 13 May 23 25 Nov 28 2022 Five Feb 13 Mar 2 Apr 17 May 22 May 26 Jun 5 23 Nov 27 2023 Four Feb 5 Feb 22 Apr 9 May 14 May 18 May 28 25 Dec 3 2024 Three Jan 28 Feb 14 Mar 31 May 5 May 9 May 19 26 Dec 1 2025 Five Feb 16 Mar 5 Apr 20 May 25 May 29 Jun 8 23 Nov 30 2026 Three Feb 1 Feb 18 Apr 5 May 10 May 14 May 24 25 Nov 29 2027 Two Jan 24 Feb 10 Mar 28 May 2 May 6 May 16 26 Nov 28 2028 Five Feb 13 Mar 1 Apr 16 May 21 May 25 Jun 4 24 Dec 3 2029 Three Jan 28 Feb 14 Apr 1 May 6 May 10 May 20 26 Dec 2 2030 Five Feb 17 Mar 6 Apr 21 May 26 May 30 Jun 9 23 Dec 1 Year of Sundays after Septuagesima The First Day Rogation Ascension Sundays after Advent Easter Day Whitsunday our Lord Epiphany Sunday of Lent Sunday Day Trinity Sunday 2031 Four Feb 9 Feb 26 Apr 13 May 18 May 22 Jun 1 24 Nov 30 2032 Two Jan 25 Feb 11 Mar 28 May 2 May 6 May 16 26 Nov 28 2033 Five Feb 13 Mar 2 Apr 17 May 22 May 26 Jun 5 23 Nov 27 2034 Four Feb 5 Feb 22 Apr 9 May 14 May 18 May 28 25 Dec 3 2035 Two Jan 21 Feb 7 Mar 25 Apr.