Mémoire De Recherche De Master 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amy and Amber Free

FREE AMY AND AMBER PDF Kelly Mckain | 96 pages | 07 Mar 2011 | Little Tiger Press Group | 9781847151599 | English | London, United Kingdom Love Island: Amy reveals how she ALWAYS managed to break the rules | Closer Love Island winner Amber Gill has responded to claims Amy and Amber a 'feud' between her and co-star Amy Hart, following Amy and Amber that the two had fallen out after Amber 'stole' her spot on Loose Women. Speaking to Heart. Read more: Kerry Katona defends daughter, 16, after she uses weight loss shakes: 'she looks amazing'. She also spoke about the potential of joining Loose Women full time, saying: "You know what? I felt more comfortable on there than what I thought I would as a panelist, so I would love to. I had such a good time and I like being able to say my opinion and have my point of view and have different points of view. So, yeah, it was loads of fun. This comes after it was reported that Amy and Amber were embroiled in a 'feud' following claims Amber had 'stolen' the Loose Women job from Amy. A source told the Mirror of Amber: "She is opinionated, outspoken and sassy — all the ingredients to Amy and Amber a perfect Loose Woman. Bosses are excited Amy and Amber see how it goes. Amber and her partner Greg Amy and Amber were crowned winners of Love Island when the series concluded last month. Amy opted to leave the villa early after splitting with Curtis Pritchard following the dramatic events of Casa Amor. -

Ebury Publishing Spring Catalogue 2019

EBURY PUBLISHING SPRING CATALOGUE 2019 The Healing Self Supercharge your immune system and stay well for life Deepak Chopra with Rudolph E Tanzi Combining the best current medical knowledge with a new approach grounded in integrative medicine, Dr Chopra and Dr Tanzi offer a groundbreaking model of healing and the immune system. Heal yourself from the inside out Our immune systems can no longer be taken for granted. Current trends in public healthcare are disturbing: our increased air travel allows newly mutated bacteria and viruses to spread across the globe, antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria outstrip the new drugs that are meant to fight them, deaths due to hospital-acquired infections are increasing, and the childhood vaccinations of our aging population are losing their effectiveness. Now more than ever, our well-being is at a dangerous crossroad. But there is hope, and the solution lies within ourselves. The Healing Self is the new breakthrough book in self-care by bestselling author and leader in integrative medicine Deepak Chopra and Harvard neuroscientist Rudolph E Tanzi. They argue that the brain possesses its own lymphatic system, meaning it is also tied into the body’s general immune system. Based on this brand new discovery, they offer new ways of January 2019 increasing the body’s immune system by stimulating the brain 9781846045714 and our genes, and through this they help us fight off illness £6.99 : Paperback and disease. Combined with new facts about the gut 304 pages microbiome and lifestyle changes, diet and stress reduction, there is no doubt that this ground-breaking work will have an important effect on your immune system. -

Prince Harry Supports Meghan

FIRST FOR CELEBRITY NEWS ISSUE 1141 ● JULY 3 2018 ● £2 WEEKLY PRINCE HARRY SUPPORTS MEGHAN HOW DOTING HARRY’S BEEN HER ROCK DURING AN EMOTIONAL WEEK WORLD CUP EXCLUSIVE ENGLAND STAR KYLE VICTORIA ROI FR €3.80 BECKHAM Auz $7.99 Malta €4.25 Malta WALKER CDN $7.99 CDN $7.99 NL €4.75 NL €4.75 AT HOME WITH OPENS UP Esp/Por €3.80Esp/Por €4.80 Italy Aus €6.10 Ger €5.30 Export £2.60/€4.90 £2.60/€4.90 Export inc GST HIS GIRLFRIEND ABOUT HER €2.81 ANNIE KILNER MARRIAGE ‘I AM ‘ANNIE HAS TRYING SUPPORTED ME TO BE THE FROM DAY ONE BEST WIFE – HOPEFULLY THAT I I CAN DO MY CAN BE – FAMILY PROUD’ IT’S NOT EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW AND PICTURES AT HOME EASY’ THE VERSION OF OF THE VERSION THIS EDITION WAS ATCURRENT THE TIME PRESS OF GOING TO VERSIONS – OTHER MAY OF THIS ISSUE THE BE DISTRIBUTED, OF WHICH CONTENTS THE FROM VARY MAY OF THIS CONTENTS MAGAZINE OK! CONTENTS NEWSAND INTERVIEWS THEDUKEANDDUCHESSOFSUSSEXhead to ISSUEJULY the races for Meghan’s Royal Ascot debut THOMASMARKLEopens up about ust a month after tying missing his daughter’s wedding the knot, the Duke and ZARAand MIKETINDALLwelcome Duchess of Sussex joined a baby girl! other senior members of J DECLANDONNELLYand his wife ALI the royal family for a day at ASTALLlead the way at Ascot the races last week. VICTORIABECKHAM praises husband OK! was at Royal Ascot the DAVID as she steps out in New York day Meghan made her debut ANTMCPARTLIN there, but despite the smile and his new girlfriend KIMKARDASHIAN plastered across her face, the week didn’t get returns to Paris LUCYMECKLENBURGH RYAN off to the best start for the newest member of and the royal family. -

Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance : New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV

This is a repository copy of Love Island, social media, and sousveillance : new pathways of challenging realism in reality TV. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/149308/ Version: Published Version Article: L'Hoiry, X. orcid.org/0000-0001-9138-7666 (2019) Love Island, social media, and sousveillance : new pathways of challenging realism in reality TV. Frontiers in Sociology, 4. 59. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 02 August 2019 doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059 Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV Xavier L’Hoiry* Department of Sociological Studies, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom This paper explores the changing nature of audience participation and active viewership in the context of Reality TV. Thanks to the ongoing rise of social media, fans of popular entertainment programmes continue to be engaged in new and innovative ways across a number of platforms as part of an ever-expanding interactive economy. -

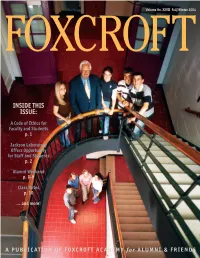

Inside This Issue

FOXCROFTVolume No. XXVII Fall/Winter 2004 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: A Code of Ethics for Faculty and Students p. 1 Jackson Laboratory Offers Opportunity for Staff and Students p. 2 Alumni Weekend p. 8-9 Class Notes p. 10 ....and more! A PUBLICATION OF FOXCROFT ACADEMY for ALUMNI & FRIENDS Dear Friends of Foxcroft Academy: his September I looked forward to the first morning of school when I, along with faculty and staff, welcomed new and return- T ing families and their students to our campus at Foxcroft Academy. This year, my second at Foxcroft Academy, it was a pleasure to greet 370 local day students as well as 61 students whose fam- ilies or towns pay tuition directly to the Academy, among which Foxcroft Academy are 26 boarding students, both domestic and international. Board of Trustees I would like to say to our families: thank you for the privilege of educating your children. As an independent school we understand President, Vandy E. Hewett ’75 that we must earn the right to educate the students who attend Vice President, Peter W. Culley ’61 Foxcroft Academy. While historically Foxcroft, and then Dover, and more Secretary, Lois W. Reynolds ’54 recently, Monson, Charleston, and Sebec have chosen to send their students Treasurer, Donna L. Hathaway ’66 to the Academy, we never take for granted this tremendous privilege given to us by the Susan M. Almy families and towns who have Foxcroft Academy as their school of choice. William C. Bisbee Others too have recognized the quality of education provided by the Academy because Rebecca R. -

Workers Are Using Laser Pens to Take on 'Bully Birds'

11/9/2018 Workers are using laser pens to take on ‘bully birds’ for attacking tourists | Daily Mail Online Tuesday, Sep 11th 2018 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel DailyMailTV Latest Headlines Royal Family News World News Arts Headlines France Pictures Most read Wires Discounts Login ADVERTISEMENT Ad Ad closed by Stop seeing this ad Why this ad? Mayores de 60 en España considerad leer esto antes de ir al médico Mayores de 60 en España considerad leer esto antes de ir al médico VISITAR Geesebusters! Workers are using laser Site Web Enter your search pens to take on ‘bully birds’ for ADVERTISEMENT attacking tourists and scaring off the indigenous geese in Cambridge Cambridge University staff are using laser torches to fend off aggressive geese Porters use devices to scare off Canada geese, fouling lawns at King’s College The birds were once seen swooping down and knocking two tourists By DAILY MAIL REPORTER PUBLISHED: 01:58 BST, 31 August 2018 | UPDATED: 01:58 BST, 31 August 2018 6 20 shares View comments University staff are using laser torches to fend off aggressive geese that are proving a health hazard and attacking tourists. Porters are using the devices to scare off a gaggle of Canada geese that are fouling the lawns at King’s College, Cambridge, and dive-bombing visitors punting on the River Cam. The birds were once seen swooping down and knocking two tourists into the water. ‘The Canada geese are big-bully birds and they have scared off the indigenous birds,’ said Philip Isaac, college bursar. -

Ebury Publishing Spring Catalogue 2020

EBURY PUBLISHING SPRING CATALOGUE 2020 Dracula (BBC Tie-in edition) Bram Stoker – foreword by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat The official tie-in edition of Bram Stoker's iconic vampire novel, accompanying the BBC series with a foreword by producers Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat “We are in Transylvania; and Transylvania is not England. Our ways are not your ways, and there shall be to you many strange things.” Bram Stoker’s classic horror novel tells the story of English lawyer Jonathan Harker. Travelling to Transylvania to meet his reclusive client, Count Dracula, Harker soon discovers Dracula’s true nature: he is a centuries-old monster with an insatiable appetite for blood! Sensing new opportunities to spread his vampire curse, Dracula sets his sights on England. Ranged against him, the wily Professor Van Helsing and a dedicated band of young men and women. But who – living, dead or undead – can stop him? Accompanying the new BBC series from Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, creators of Sherlock, starring Claes Bang as Count Dracula. This Tie-in edition will introduce a whole new generation of fans to the wonders of Stoker's original novel. Abraham Stoker was born in Dublin on 8 November 1847. He graduated in Mathematics from Trinity College, Dublin in 1867 and then worked as a civil servant. In 1878 he married Florence Balcombe. He later moved to London and became January 2020 business manager of his friend Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre. 9781785945168 He wrote several sensational novels including novels The £7.99 : Paperback Snake's Pass (1890), Dracula (1897), The Jewel of Seven Stars 432 pages (1903), and The Lair of the White Worm (1911). -

By Using the Site You Agree to Our Privacy Settings

ADVERTISEMENT Saturday, Jan 26th 2019 7PM 3°C 10PM 3°C 5-Day Forecast ADVERTISEMENT Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel DailyMailTV Latest Headlines Royal Family News World News Arts Headlines France Pictures Most read Wires Discounts Login Site Web Enter your search ADVERTISEMENT Like +1 Daily Mail Daily Mail Follow Follow @DailyMail Daily Mail Follow Follow @dailymailuk Daily Mail DON'T MISS Love Island's Megan Barton Hanson announces she's SPLIT from beau Wes Nelson... as they vow to co- parent their 'incredibly wonderful' hamster in hilarious statement Lisa Armstrong appears stony-faced as she shows off her new hairdo in London... after slamming ex Ant McPartlin for 'cruel and wrong' treatment Adele enjoys rare date night with husband Simon Konecki as they arrive backstage at Elton John concert Enjoying a relaxed date night Matthew Wright, 53, and wife Amelia welcome miracle baby daughter following eight years of IVF treatment Couple are now proud parents Zara McDermott insists Adam Collard 'did NOT bad-mouth' Ferne McCann's daughter and claims his eye is in pain after TOWIE star 'THREW container' Michael Jackson documentary Leaving Neverland sickens Sundance with 'sexually explicit and devastating' proof that he 'sexually abused children' Dani Dyer looks sensational in barely- +21 there bikini during sun- soaked Dubai holiday... while beau Jack Fincham remains at home Pregnant Jemma Lucy showcases her blossoming baby bump for night out in sexy ensemble... after fearing she will be 'ATTACKED' over pregnancy news Gemma Collins reveals VERY painful Dancing On Ice injury as she visits the show's physio.. -

Weekly Highlights Week 41/42: Sat 10Th - Friday 16Th October 2020

Weekly Highlights Week 41/42: Sat 10th - Friday 16th October 2020 John Bishop’s Great Whale Rescue Monday & Tuesday, 9pm John Bishop goes on an emotional journey with two beluga whales. This information is embargoed from reproduction in the public domain until Tue 6th October 2020. Press contacts Further programme publicity information: ITV Press Office [email protected] www.itv.com/presscentre @itvpresscentre ITV Pictures [email protected] www.itv.com/presscentre/itvpictures ITV Billings [email protected] www.ebs.tv This information is produced by EBS New Media Ltd on behalf of ITV +44 (0)1462 895 999 Please note that all information is embargoed from reproduction in the public domain as stated. Weekly highlights Catchphrase Celebrity Special Saturday, 5.30pm 10th October ITV Stephen Mulhern presents as three more stars say what they see for the chance to secure a massive amount of money for charity, but who has what it takes to win? The host and Mr Chips have visual clues for guests Dion Dublin, Rachel Riley and Tim Vine as they try to guess the familiar phrases in the animated clues. If they can ‘say what they see’, they could win a £50,000 jackpot for their chosen charity. The Chase Celebrity Special Saturday, 6.30pm 10th October ITV Bradley Walsh hosts a special celebrity edition of the quiz show in which a group of stars take on the mighty Chasers to see if they can win some big money for charity. Comedian Susan Calman, broadcaster Dermot Murnaghan, athlete Perri Shakes- Drayton and actor Omid Djalil hope to win big for their chosen charities as they take on one of the country’s finest quiz brains. -

Women Should Freeze Their Eggs in Their TWENTIES If They Want to Put

Privacy Policy Feedback Friday, Aug 10th 2018 10PM 12°C 1AM 11°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Fashion Finder Latest Headlines Health Health Directory Discounts Login ADVERTISEMENT Women should freeze their eggs in Site Web Enter your search their TWENTIES if they want to put off ADVERTISEMENT being a mother or it will be too late, experts warn Women who want to be a mother later in life should freeze their eggs early Most women do the procedure in their 30s- but often have little success Specialists worry that fertility clinics encourage women to delay motherhood By BEN SPENCER MEDICAL CORRESPONDENT FOR THE DAILY MAIL PUBLISHED: 00:04, 8 August 2018 | UPDATED: 07:56, 8 August 2018 17 325 shares View comments Women who want to delay motherhood have the best chance if they freeze their eggs in their early 20s, experts say. The vast majority of women who go through the procedure do so in their late 30s – by which time they have very little chance of success. Specialists are increasingly concerned that fertility clinics encourage women to delay motherhood for too long by offering them the safety net of egg freezing. Like +1 Daily Mail Daily Mail Follow Follow @DailyMail Daily Mail Follow Follow @MailOnline Daily Mail DON'T MISS Ant and Dec PICTURE EXCLUSIVE: Duo look EXCLUSIVE: Duo look glum as they are seen for the first time since announcing break from presenting as a pair for ONE YEAR Jennifer Lopez, 49, flaunts her famously peachy derriere as she enjoys a workout with boyfriend -

100 Ways for Every Girl to Look and Feel Fantastic Free

FREE 100 WAYS FOR EVERY GIRL TO LOOK AND FEEL FANTASTIC PDF Alice Hart-Davis,Beth Hindhaugh | 128 pages | 06 Sep 2012 | Walker Books Ltd | 9781406337549 | English | London, United Kingdom Walker Books - Ways for Every Girl to Look and Feel Fantastic There seems to be no escape. Have thighs like her! This barrage of unrealistic body ideals cause many parents to worry about how these images negatively affect the self-image of their teenage daughters. Hart-Davis said. While the book offers beauty tips that every girl loves, like taking care of her skin, shaping her 100 Ways for Every Girl to Look and Feel Fantastic, and learning some new eyeliner looks, it goes much farther. The authors have delved beyond the hair-skin-and-makeup part of beauty to really explore how looks are tied up with self-confidence and why this matters so much to us. In addition to telling teenagers how to style their hair and try their hand at nail design, the book supports inner beauty and emotional well-being, from practicing 100 Ways for Every Girl to Look and Feel Fantastic happy, to improving posture it helps confidence and working out who they are as individuals. The goal is that one day teen girls will close glossy magazines and walk past giant billboards with unattainable celebrity goals in lieu of being their own unique person. Gorgeous Giveaways. Fast Free Shipping Worldwide. Get this widget. All Rights Reserved. COM without prior consent is strictly prohibited. Log in Join. Share this. Beth Hindhaugn and Alice Hart-Davis. -

Comic Relief Annual Report and Accounts 2017/18

COMIC RELIEF ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2017/18 “WE HAVE ACHIEVED SOME CONTENTS INCREDIBLE THINGS IN 2017/18 AT COMIC RELIEF – A YEAR IN WHICH WE The big picture: our 2017/18 in overview 2 INSPIRED A LOT OF PEOPLE Who we are 2 Highlights 4 Chief Executive’s Review 8 TO GET ACTIVE, RAISED Chair’s Report 10 A LOT OF MONEY FOR In close-up: our strategic report 12 How Comic Relief works 12 Our priorities and objectives 13 BRILLIANT CAUSES, AND Our achievements and performance 14 Looking ahead 26 MADE REAL PROGRESS Principle risks and uncertainties 28 Financial review 32 TOWARDS ENSURING THAT Our approach to fundraising 37 COMIC RELIEF’S FUTURE Structure, governance and management 38 Statement of Trustees’ responsibilities 40 WILL BE AS SUCCESSFUL Reference and administrative details 41 Independent auditor’s report 42 AS THE PAST 30-PLUS Financial statements 44 YEARS HAVE BEEN...” Liz Warner, Comic Relief Chief Executive 1 Charity Projects (better known as Comic Relief) The big picture: our 2017/18 in overview Annual Report & Accounts 2018 Who we are MAKING ENTERTAINMENT COUNT FOR OVER 30 YEARS. Ever since our first broadcast from a refugee IN TOTAL, “I’VE BEEN INVOLVED WITH camp in Sudan on Christmas Day in 1985, COMIC RELIEF Comic Relief has had a clear goal – to harness COMIC RELIEF FROM THE VERY the power of entertainment to help millions HAS TO DATE of people change their lives for the better. RAISED OVER BEGINNING. HAVING A LAUGH From the first Red Nose Day telethon in 1988, £1.3 BILLION AND BEING ACTIVE HAS BEEN our success has been based not just on (YES, BILLION).