International Conference on Built Environment in Developing Countries (Icbedc 2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspen Group Together with Oxley Holdings Aim to Bring Mixed-Use Integrated Development with Modern Conveniences to Air Itam

PRESS RELEASE - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Aspen Group together with Oxley Holdings aim to bring mixed-use integrated development with modern conveniences to Air Itam ▪ The Group together with Oxley Holdings Limited are investing RM165 mil to acquire a total of 7 pieces of freehold land measuring 29.05 acres (1.27 million sq ft) in Paya Terubong via a conditional sale and purchase agreement with Geo Valley Sdn Bhd ▪ The proposed development is a mixed-use development comprising residential towers, service apartments, retail lots and a community centre ▪ The land is strategically located within a matured suburban township serving a community as many as 400,000 people. ▪ The development will benefit from existing daily lifestyle amenities and well- connected excellent infrastructure in a matured residential township, including the ongoing Jalan Bukit Kukus Highway Project which will eventually link the Air Itam township to the FTZ area of Bayan Lepas, Penang International Airport and two Penang Bridges via the future Pan Island Link Singapore, 22 June 2019 – Aspen (Group) Holdings Limited (“Aspen” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”), today announced that its subsidiary company, Aspen Park Hills Sdn Bhd signed a conditional sales and purchase agreement with Geo Valley Sdn. Bhd., to acquire a total of seven pieces of freehold land measuring 29.05 acres in Paya Terubong for RM165mil. Geo Valley Sdn. Bhd. will also invest 25% equity in Aspen Park Hills Sdn Bhd. Parts of the land are currently approved by the local council for mixed development and for the construction of part of the Jalan Bukit Kukus paired road linking Thean Teik Highway from Air Itam to Jalan Paya Terubong. -

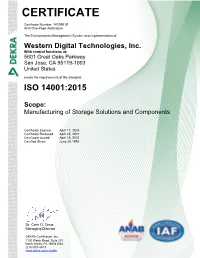

ISO 14001 Certification

CERTIFICATE Certificate Number: 141099.01 With One Page Addendum The Environmental Management System and implementation of: Western Digital Technologies, Inc. With central functions at: 5601 Great Oaks Parkway San Jose, CA 95119-1003 United States meets the requirements of the standard: ISO 14001:2015 Scope: Manufacturing of Storage Solutions and Components Certificate Expires: April 17, 2024 Certificate Reissued: April 25, 2021 Certificate Issued: April 18, 2021 Certified Since: June 25,1995 Dr. Cem O. Onus Managing Director DEKRA Certification, Inc. 1120 Welsh Road, Suite 210 North Wales, PA 19454 USA (215) 997-4519 www.dekra.us/en/audits CERTIFICATE ADDENDUM Certificate Number: 141099.01 Addendum Page: 1 of 1 Certificate Expires: April 17, 2024 Certificate Reissued: April 25, 2021 The Environmental Management System and implementation of: Western Digital Technologies, Inc. meets the requirements of the standard: ISO 14001:2015 Site Address Scope per Site: Western Digital Technologies, Inc. (Central Function) Central management of the EMS 5601 Great Oaks Parkway, San Jose, CA 95119-1003, United States HGST, Inc. Manufacturing of Storage Solutions Wafer Fab Manufacturing and Components 5601 Great Oaks Parkway, San Jose, CA 95119-1003 United States HGST Malaysia Sdn. Bhd. Manufacturing of Storage Solutions Sama Jaya Free Industrial Zone, Muara Tabuan, Kuching, and Components Sarawak, Malaysia 93450 Western Digital Storage Technologies (Philippines) Corp. Manufacturing of Storage Solutions 109 Technology Avenue, Special Export Processing Zone, and Components Laguna Technopark, Binan City, Laguna, Philippines 4024 HGST (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. Manufacturing of Storage Solutions #7 Lanhua Road, Futian Free Trade Zone, and Components Shenzhen, P.R. China 518038 Manufacturing of Storage Solutions HGST Japan, Ltd. -

(Emeer 2008) State: Pulau Pinang

LIST OF INSTALLATIONS AFFECTED UNDER EFFICIENT MANAGEMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY REGULATIONS 2008 (EMEER 2008) STATE: PULAU PINANG No. Installation Name Address BADAN PENGURUSAN BERSAMA PRANGIN MALL, PEJABAT 1 PRANGIN MALL PENGURUSAN, TINGKAT 5, PRANGIN MALL, NO.33, JALAN DR. LIM CHWEE LEONG, 10100 PULAU PINANG 161,KAWASAN INDUSTRI,11900 BAYAN LEPAS FTZ,BAYAN LEPAS, PULAU 2 RAPID PRECISION PINANG 3 TECO INDUSTRY (MALAYSIA) 535/539,LRG PERUSAHAAN BARU,13600 PERAI,PULAU PINANG 4 MEGAMALL PENANG 2828, JALAN BARU, BANDAR PERAI JAYA, 13600 PERAI, PULAU PINANG PLOT 17A,JLN PERUSAHAAN,13600 KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN PRAI 5 METECH ALUMINIUM SDN BHD IV,PRAI, PULAU PINANG ALLIANCE RUBBER PRODUCTS SDN 2714, LRG INDUSTRI 15, KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN BKT PANCHOR, 6 BHD NIBONG TEBAL, 14300, PULAU PINANG BENCHMARK ELECTRONICS (M) SDN PLOT 17A & B, TECHNOPLEX, MEDAN BAYAN LEPAS, BAYAN LEPAS 7 BHD - PRECISION TECHNOLOGIES INDUSTRIAL PARK, PHASE 4, 11900 BAYAN LEPAS, PULAU PINANG NO. 2515, TINGKAT PERUSAHAAN 4A, PERAI FREE TRADE ZONE, 13600 8 TONG HEER FASTENERS CO. SDN BHD PERAI, PULAU PINANG 9 NI MALAYSIA SDN BHD NO. 8, LEBUH BATU MAUNG 1, 11960 BAYAN LEPAS, PULAU PINANG 10 EPPOR-PACK SDN BHD 2263, PERMATANG KLING, 14300 NIBONG TEBAL, PULAU PINANG FLEXTRONICS SYSTEMS (PENANG) PMT 719, LINGKARAN CASSIA SELATAN, 14100 SIMPANG AMPAT, PULAU 11 SDN BHD PINANG 12 GURNEY PARAGON MALL 163-D, PERSIARAN GURNEY, 10250, PULAU PINANG BENCHMARK ELECTRONICS (M) SDN BAYAN LEPAS FREE INDUSTRIAL ZONE PHASE 1, 11900 BAYAN LEPAS, 13 BHD - ELECTRONIC MANUFACTURING PULAU PINANG SERVICES -

Non-Related Party Transaction Greatech

ANNOUNCEMENT SUBJECT: TRANSACTION (CHAPTER 10 OF LISTING REQUIREMENTS) - NON-RELATED PARTY TRANSACTION GREATECH TECHNOLOGY BERHAD (“GREATECH” OR “THE COMPANY”) ACQUISITION BY GREATECH INTEGRATION (M) SDN BHD (COMPANY NO. 447240-X) (“GIM”), A WHOLLY OWNED SUBSIDIARY OF GREATECH, OF A PIECE OF VACANT LEASEHOLD LAND EXPIRING ON 17 AUGUST 2074 HELD UNDER NO. H.S.(D) 47093, PT5822, MUKIM 13, DAERAH SEBERANG PERAI SELATAN, NEGERI PULAU PINANG WITH LAND AREA MEASURING APPROXIMATELY 4.2067 ACRES OR 183,243.85 SQUARE FEET (“LAND”) FROM PENANG DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (“VENDOR”) FOR A PURCHASE CONSIDERATION OF APPROXIMATELY RM8,245,973.25 (“PURCHASE CONSIDERATION”) TO BE SATISFIED IN CASH (“ACQUISITION OF LAND”) 1. INTRODUCTION Reference is made to the Company’s Prospectus dated 13 May 2019 in relation to its initial public offering in conjunction with the listing of and quotation for the Company’s entire issued share capital on the ACE Market of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad. GIM has on 22 April 2019 received a letter of offer from the Vendor in respect of the Acquisition of Land. The offer has been accepted by GIM on 17 May 2019, subject to the terms and conditions under the Sale and Purchase Agreement (“ SPA ”) to be entered between the Vendor and GIM. The Board of Directors of the Company (“ Board ”) wishes to announce that on 20 June 2019, GIM entered into an SPA with the Vendor for the Acquisition of Land on an “as is where is basis” free from all encumbrances of whatsoever and with legal and vacant possession but subject to the Category, the Express Conditions and restrictions implied by the National Land Code, 1965 and upon the terms and conditions of the SPA. -

The State of Penang, Malaysia

Please cite this paper as: National Higher Education Research Institute (2010), “The State of Penang, Malaysia: Self-Evaluation Report”, OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development, IMHE, http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/regionaldevelopment OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development The State of Penang, Malaysia SELF-EVALUATION REPORT Morshidi SIRAT, Clarene TAN and Thanam SUBRAMANIAM (eds.) Directorate for Education Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) This report was prepared by the National Higher Education Research Institute (IPPTN), Penang, Malaysia in collaboration with a number of institutions in the State of Penang as an input to the OECD Review of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. It was prepared in response to guidelines provided by the OECD to all participating regions. The guidelines encouraged constructive and critical evaluation of the policies, practices and strategies in HEIs’ regional engagement. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the National Higher Education Research Institute, the OECD or its Member countries. Penang, Malaysia Self-Evaluation Report Reviews of Higher Education Institutions in Regional and City Development Date: 16 June 2010 Editors Morshidi Sirat, Clarene Tan & Thanam Subramaniam PREPARED BY Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang Regional Coordinator Morshidi Sirat Ph.D., National Higher Education Research Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia Working Group Members Ahmad Imran Kamis, Research Centre and -

Chapter 4: Environment

Penang Economic and Development Report 153 2019/2020 4. Environment Environmental quality is considered to be a public levels of up to 50 are considered good, between 51 good. It affects the public and the community in and 100 moderate, 101 and 200 unhealthy, 201 and terms of economic, social welfare, and quality of 300 very unhealthy, and 300 and above hazardous. life. Ecological sustainability is a key factor for An API system includes the major air pollutants sustainable economic and social development. which may cause potential harm to human health if The most pressing environmental issues in Penang they reach unsafe levels. The air pollutants included are air and water pollution, flash floods, waste in Malaysia’s API are ozone (O3), carbon monoxide management, and landslides. Short-term action is (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2), needed while maintaining a long-term perspective. suspended particulate matter of less than 10 microns in size (PM10) and suspended particulate matter of less than 2.5 microns in size (PM2.5) (Department of 4.1 Pollution Environment Malaysia, 2018). Different types of environmental pollution have The air quality of Penang is monitored at four been reported in Penang, the major ones being open stations, Seberang Jaya, Seberang Perai, Balik burning, air pollution, and water pollution. These Pulau, and Minden. In 2019, the overall air quality in pose serious risks to the environment, public health, Penang worsened as the number of days with good and even the economy. API levels decreased and the number of unhealthy days increased compared with 2018 (Table 4.1). -

SHORT COMMUNICATION Termite Infestation Associated With

Tropical Life Sciences Research, 24(2), 91–95, 2013 SHORT COMMUNICATION Termite Infestation Associated with Type of Soil in Pulau Pinang, Malaysia (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) 1,2Abdul Hafiz Ab Majid* and 2Abu Hassan Ahmad 1Department of Entomology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583-0816, USA 2School of Biological Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 USM, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia Abstrak: Sembilan sampel tanah dari sembilan bangunan yang diserang oleh Coptotermes gestroi di Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, telah diuji untuk menentukan jenis tekstur tanah. Prosedur analisis tekstur tanah menggunakan kaedah hidrometer. Empat daripada sembilan bangunan (44%) dikenal pasti sebgai tanah jenis liat pasir. Manakala lima daripada sembilan bangunan (56%) telah dikenal pasti sebagai tanah jenis gembur berpasir. Kata kunci: Coptotermes gestroi, Anai-anai, Tanah Liat Pasir, Tanah Gembur Berpasir, Kaedah Hidrometer Abstract: Nine soil samples from nine buildings infested with Coptotermes gestroi in Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, were tested for the type of soil texture. The soil texture analysis procedures used the hydrometer method. Four of nine buildings (44%) yielded loamy sand-type soil, whereas five of nine buildings (56%) contained sandy loam-type soil. Keywords: Coptotermes gestroi, Termites, Loamy Sand, Sandy Loam, Hydrometer Method Subterranean termites, especially of the genus Coptotermes, are a widespread insect pest in Southeast Asia (Abdul Hafiz & Abu Hassan 2009). These termites were reported as the most destructive subterranean termite in Thailand and Malaysia (Abdul Hafiz & Abu Hassan 2009, 2008; Kirton & Brown 2003). The subterranean termite is a social insect with a mysterious life cycle. With cryptobiotic life and constant underground movement, subterranean termites can strike unexpectedly anywhere and can cause serious damage to buildings and products containing cellulose (Kamble & Davis 2005). -

1970 Population Census of Peninsular Malaysia .02 Sample

1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE DATA DOCUMENTATION AND CODEBOOK 1970 POPULATION CENSUS OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA .02 SAMPLE - MASTER FILE CONTENTS Page TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON THE DATA TAPE 1 DESCRIPTION OF THE DATA FILE 2 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1: HOUSEHOLD RECORD 4 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2: PERSON RECORD (AGE BELOW 10) 5 INDEX OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3: PERSON RECORD (AGE 10 AND ABOVE) 6 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 1 7 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 2 15 CODES AND DESCRIPTIONS OF VARIABLES FOR RECORD TYPE 3 24 APPENDICES: A.1: Household Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 4) 33 A.2: Individual Form for Peninsular Malaysia, Census of Malaysia, 1970 (Form 5) 34 B.1: List of State and District Codes 35 B.2: List of Codes of Local Authority (Cities and Towns) Codes within States and Districts for States 38 B.3: "Cartographic Frames for Peninsular Malaysia District Statistics, 1947-1982" by P.P. Courtenay and Kate K.Y. Van (Maps of Adminsitrative district boundaries for all postwar censuses). 70 C: Place of Previous Residence Codes 94 D: 1970 Population Census Occupational Classification 97 E: 1970 Population Census Industrial Classification 104 F: Chinese Age Conversion Table 110 G: Educational Equivalents 111 H: R. Chander, D.A. Fernadez and D. Johnson. 1976. "Malaysia: The 1970 Population and Housing Census." Pp. 117-131 in Lee-Jay Cho (ed.) Introduction to Censuses of Asia and the Pacific, 1970-1974. Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Population Institute. -

Capitalizing on WĞŶĂŶŐ͛Ɛ ǀăůƶğ Ɖƌžɖžɛŝƚŝžŷ As a Destination Of

Invest in Penang 2015 Capitalizing on WĞŶĂŶŐ͛ƐǀĂůƵĞƉƌŽƉŽƐŝƚŝŽŶas a destination of choice for investors LJĂƚŽ͛>ĞĞ<ĂŚŚŽŽŶ ͞ƵƐŝŶĞƐƐΘŝŶǀĞƐƚŵĞŶƚŽƉƉŽƌƚƵŶŝƚŝĞƐŝŶWĞŶĂŶŐ͕DĂůĂLJƐŝĂ͟ Penang in the news: An industrial base state, heritage city and campus for technology ¾ Top 10 dynamic industrial cluster locations in the world to have demonstrated a successful manufacturing experience among developing economies (UNIDO Industrial Development Report 2009) ¾ Top 31 Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) - locations of the future ;<WD'͛Ɛ ͞džƉůŽƌŝŶŐ Global &ƌŽŶƚŝĞƌƐ͟ Report 2009) ¾ Georgetown ʹ UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008 ¾ The 16th most livable cities in Asia (ECA Intl. 2014) ¾ Top in Green initiatives in Malaysia ¾ C.A.T. Governance praised for anti-corruption efforts (Transparency International, AG Report 2010) ¾ 4th most charismatic city globally 2016 (Lonely Planet 2015) ¾ Top 10 best city to visit in the world (The Guardian 2014) ¾ Top culinary spot (Lonely Planet 2014) ¾ Top 8 islands in the world ͚zŽƵ must see before you die' (Yahoo! Travel, Feb 2011) ¾ Top 15 best street art in the world (The Guardian 2013) 1.7 mil 1,031 sq km population area (68.8% (green zone) working age group) Multilingual 821k workforce (English, Malay, Mandarin, Tamil (254k ʹ etc) manufacturing) 54.8 B GDP 40 years of (7% cumulative contribution to national GDP) industrial intelligence Jobs & GDP Penang has Growth evolved and Innovation & Knowledge driven Towards a knowledge based taken on a new Investment & economy Productivity driven dynamism Labour driven 2010 and 60-70s -

Executive Summary

THE PROPOSED PAN ISLAND LINK 1 HIGHWAY PROJECT, PENANG EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Penang State Government proposes to build a new highway that will connect the Gurney Drive area in the northern part of the island to Bayan Lepas in the south. It will form a second north-south spine road that will provide relief to the Tun Dr. Lim Chong Eu (LCE) Expressway. 1.1 Project Title This Environmental Impact Assessment study is prepared for the “Proposed Pan Island Link 1 (PIL 1) Highway, Penang”. Henceforth, it shall be referred to as the PIL1 Project. 1.2 PROJECT PROPONENT AND CONSULTANTS i. Project Proponent The proponent for the PIL1 Project is the Penang State Government. The contact details are as follows: PENANG STATE GOVERNMENT Level 25, KOMTAR, 10503 Pulau Pinang. Tel: 604-261 5617 Fax: 604-261 8618 E-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Dato’ Seri Farizan Bin Darus (Penang State Secretary) ES - 1 THE PROPOSED PAN ISLAND LINK 1 HIGHWAY PROJECT, PENANG ii Project Delivery Partner The Project Delivery Partner is SRS Consortium. The contact details are as follows: SRS CONSORTIUM 73-3A, Ideal @ The One, Jalan Mahsuri, 11950 Bayan Lepas, Pulau Pinang. Tel: 604-641 6888 Fax: 604-641 1776 E-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Mr. Andy Lee Choon Foh iii EIA Consultant The consultant undertaking the EIA study is Wiranda (M) Sdn. Bhd. The contact details are as follows: WIRANDA (M) SDN BHD No. 3374, Jalan 18/31, Taman Sri Serdang, 43300 Seri Kembangan, Selangor Darul Ehsan. Tel: 03-8942 3413 Fax: 03-8948 5912 E-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Mr. -

KK = Klinik Kesihatan Timur Laut, 11200 Pulau Pinang

DAERAH DAERAH DAERAH DAERAH DAERAH TIMUR LAUT BARAT DAYA SEBERANG PERAI UTARA SEBERANG PERAI TENGAH SEBERANG PERAI SELATAN KK Seberang Jaya, KK Teluk Bahang, KK Butterworth, KK Sungai Dua, Lot 340, Mukim 1, KK Nibong Tebal, Lot 669, Mukim 2, Lot 1699 Seksyen 4, Lot 2544, Mukim 13, Bandar Sunway, Lot 320, Mukim 17, 11050 Teluk Bahang, Jalan Bagan Luar Sungai Dua, Timur Laut, DAERAH TIMUR LAUT 13700 Seberang Jaya, 14300 Nibong Tebal, Pulau Pinang. 12000 Butterworth, 11700 Pulau Pinang. Pulau Pinang. Pulau Pinang. Tel: 04-8851951 Pulau Pinang. Tel: 04-6422201 Tel: 04-3900264 Tel: 04-5931355 Fax : 04-8811333 Tel: 04-3233333 Fax : 04-3905424 KK Jalan Macalister, KK Berapit, KK Bayan Lepas, KK Kepala Batas, KK Sungai Acheh, Lot 1762, Lot 89, Mukim 7, Lot 1157, Mukim 12, Lot 1446, Mukim 6, Lot 1376, Mukim 10, Jalan Macalister, Jalan Bukit Panchor, Bayan Lepas, 13200 Kepala Batas, 14300 Nibong Tebal, Timur Laut, 14300 Nibong Tebal, 11900 Pulau Pinang. Pulau Pinang. Pulau Pinang. 10400 Pulau Pinang. Pulau Pinang. Tel: 04-6433967 Tel: 04-5753355 Tel: 04-5981733 Tel: 04-2289610 Tel: 04-5395400 KK Bayan Baru, KK Mak Mandin, KK Prai, KK Bandar Tasik Mutiara, KK Jalan Perak, Jalan Tengah, Lot 2822, Seksyen 3, Klinik Kesihatan Prai, Lot 1051 Mukim 15, Lot 808, Seksyen 2 11950 Bayan Lepas, Jalan Mak Mandin, 13700 Perai, 14100 Simpang Ampat, Jalan Perak, Timur Laut, Pulau Pinang. 13400 Butterworth, Pulau Pinang. Pulau Pinang. 10400 Pulau Pinang. Tel: 04-6425102 Pulau Pinang. Tel: 04-3901477 Tel: 04-5079855 Tel : 04-2812033 Fax: 04-6413189 Tel: 04-3244685 KK Kubang Semang, KKIA Air Putih, KK Tasek Gelugor, Lot 807, Mukim 5, KK Bukit Jambul, Lot 312, MK.E JKR KK Bukit Panchor, Lot 19944m Mukim 12, Kubang Semang, Taman Bukit Jambul, 2761 (P) Air Putih, Seberang Perai Selatan, 13300, Tasek Gelugor, 14400 Bukit Mertajam, Bukit Jambul, Timur Laut, 11000 Balik Pulau Pulau Pinang. -

06 FEB Trend of Investments in Batu Kawan Industrial Park

2021 06 FEB ANALYSING PENANG, MALAYSIA AND THE REGION Trend of Investments in Batu Kawan Industrial Park By Dr Lee Siu Ming (Senior Analyst, Socioeconomics & Statistics Programme) Executive Summary • This brief analyses the investment inflows and developments in Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP), and includes a discussion on job creation, clustering, and economic spillovers. • The percentage share of approved manufacturing investments in Seberang Perai Selatan (SPS) as a portion of the total approved manufacturing investments in Penang increased from 6% in 2015 to 27% in 2019. Investments in BKIP consist of a good combination of FDI and DDI in promoted sectors, especially in electrical and electronics (E&E), machinery and equipment (M&E), and medical technology. • Companies from United States, Germany, United Kingdom, Japan, Singapore, and Malaysia are among the largest sources of investments and re-investments into BKIP. With record-high approved FDI reported in 2019 and several mainly high-technology projects in the past few years; the multiplier effect is expected to spur the growth and development of local firms. • In terms of linkages and spillovers: BKIP (1) is an extension of Penang’s solid industrial foundation, (2) promotes industry clusters and SME development, (3) can be capitalised upon to spur developments of global business services in purpose-built offices (PBOs), and (4) upgrades the socioeconomic status of SPS. • As the state develops 1,156 acres in Batu Kawan Industrial Park 2 (BKIP2) (and more industrial areas), some key challenges persist and require attention from stakeholders in the following areas: (1) better progress in moving up the value chain, (2) cooperation to provide investors with a more seamless experience in doing business, (3) investment promotion and investor handholding, and (4) development of long-term roadmap for industries and talent in Malaysia.