You're Listening to Imaginary Worlds, a Show About How We Create Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Exploring the Experiences of Gamers Playing As Multiple First-Person Video Game Protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’S Single-Player Narrative

Exploring the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative Richard Alexander Meyers Bachelor of Arts Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Creative Practice Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords First-Person Shooter (FPS), Halo 3: ODST, Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), ludus, paidia, phenomenology, video games. i Abstract This thesis explores the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST, with a view to formulating an understanding of player experience for the benefit of video game theorists and industry developers. A significant number of contemporary console-based video games are coming to be characterised by multiple playable characters within a game’s narrative. The experience of playing as more than one video game character in a single narrative has been identified as an under-explored area in the academic literature to date. An empirical research study was conducted to explore the experiences of a small group of gamers playing through Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as a methodology particularly suited to exploring a new or unexplored area of research and one which provides a nuanced understanding of a small number of people experiencing a phenomenon such as, in this case, playing a video game. Data were gathered from three participants through experience journals and subsequently through two semi- structured interviews. The findings in relation to participants’ experiences of Halo 3: ODST’s narrative were able to be categorised into three interrelated narrative elements: visual imagery and world-building, sound and music, and character. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Firewatch Download Torrent Mac the Forest Free Download Mac

firewatch download torrent mac The Forest Free Download Mac. Nov 23, 2020 — Into the Forest PC Game Walkthrough Free Download for Mac Full version highly compressed via direct link. Into the Forest PC Game Free …. Feb 1, 2007 — Download Forest Resort Mac for Mac to collect magic to restore the forest while attending to your customers.. May 4, 2019 — The Forest free download! Download here for free! Just download and play for PC! Cracked by CPY, CODEX and SKIDROW! Free Digital College Planner Printables + Stickers. I have been out of college for a few years now, but my little brother in law … forest app. forrest gump, forrest gump quotes, forrest fenn, forrest galante, forrest fenn treasure, forest, forest whitaker, forester, forrest, forestry, forest game, forest app, forest korean drama, forest cartoon, forest green, forest of dean. RevMan Web is the online platform recommended for Cochrane intervention and flexible reviews. Log in to RevMan Web to access your review. RevMan 5 is free … forest game. Forest is an app helping you stay away from your smartphone and stay focused on your work.. The Forest Free Download PC Game Latest Update DMG For Mac OS Android APK Free Download PC Games Highly Compressed Direct Download In Parts …. Download Forest for Mac – Stay focused on your work and avoid time wasting websites with the help of this cute extension that comes with support for Chrome … Firewatch PC Game Free Download. Dalam Firewatch, Anda akan memerankan seorang tokoh bernama Henry. Ketika sedang melakukan patroli di hutan, dirinya mendapati bahwa menara pengawas telah diobrak-abrik oleh orang lain. -

Fables: the Wolf Among Us Vol. 1 Online

uhGo8 (Read free) Fables: The Wolf Among Us Vol. 1 Online [uhGo8.ebook] Fables: The Wolf Among Us Vol. 1 Pdf Free Matthew Sturges, Dave Justus ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #168069 in Books Matthew Sturges Dave Justus 2015-11-03 2015-11-03Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.20 x .40 x 6.70l, .0 #File Name: 1401256848256 pagesFables The Wolf Among Us Volume 1 | File size: 59.Mb Matthew Sturges, Dave Justus : Fables: The Wolf Among Us Vol. 1 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Fables: The Wolf Among Us Vol. 1: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. WowBy AndrewI'm a huge fan of fables got turned on it by yes playing the video game wolf among us. Although the comic fables has more of an atmosphere of most fairy tale charters and real feel of mystery and detective, the let's say cross series wolf among us is so much more suspenseful with even flashbacks and really captures the persona of the main charter bigby. Although the flashbacks were quite tedious and confusing at points it really puts you in a perspective and growing the charter of bigby for an indulgence of wanting to read more. For fables it's a good mystery read but you definitely have a pure emotion connection with characters in the "cross series".0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Fun and FantasticBy K524A fantastic adaption of an amazing game. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Music, Time and Technology in Bioshock Infinite 52 the Player May Get a Feeling That This Is Something She Does Frequently

The Music of Tomorrow, Yesterday! Music, Time and Technology in BioShock Infinite ANDRA IVĂNESCU, Anglia Ruskin University ABSTRACT Filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino have taken full advantage of the disconcerting effect that pop music can have on an audience. Recently, video games have followed their example, with franchises such as Grand Theft Auto, Fallout and BioShock using appropriated music as an almost integral part of their stories and player experiences. BioShock Infinite takes it one step further, weaving popular music of the past and pop music of the present into a compelling tale of time travel, multiverses, and free will. The third installment in the BioShock series has as its setting the floating city of Columbia. Decidedly steampunk, this vision of 1912 makes considerable use of popular music of the past alongside a small number of anachronistic covers of more modern pop music (largely from the 1980s) at crucial moments in the narrative. Music becomes an integral part of Columbia but also an integral part of the player experience. Although the soundscape matches the rest of the environment, the anachronistic covers seem to be directed at the player, the only one who would recognise them as out of place. The player is the time traveller here, even more so than the character they are playing, making BioShock Infinite one of the most literal representations of time travel and the tourist experience which video games can represent. KEYWORDS Video game music, film music, intertextuality, time travel. Introduction For every choice there is an echo. With each act we change the world […] If the world were reborn in your image, Would it be paradise or perdition? (BioShock 2 launch trailer, 2010) Elizabeth hugs a postcard of the Eiffel Tower. -

What Makes a Trophy Hunter? an Empirical Analysis of Reddit Discussions

Copyright © 2020 for this paper by its authors. Use permitted under Creative Commons License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). What makes a trophy hunter? An empirical analysis of Reddit discussions Chien Lu1, Jaakko Peltonen1, Timo Nummenmaa1, Xiaozhou Li1, and Zheying Zhang 1 Tampere University, Kalevantie 4, 33100 Tampere, Finland Abstract. In this paper, an empirical data-driven analysis of online discussions of meta-game reward systems is carried out. The data is collected from one of the biggest online discussion forums called Reddit and a text-mining technique called topic modeling is employed. Over 46000 discussion threads from the two most relevant subreddits /r/xboxachievements and /r/Trophies are analyzed and the results of topic modeling shows not only interesting topics but also the (dis)similarity between two text sources the temporal trends of topics. We have found that the volume of related discussions shows an ongoing trend. The topic model results have also revealed that some game genres are more prevalent than others and the (dis)similarities between text sources have been also discovered. Keywords: trophy hunting, Reddit, topic modeling 1 Introduction It has been noted that games can also be gamified [10], which has attracted research- ers’ attention [9,14]. Early work on applying badge systems to non-game contexts have also used game achievement systems as a source of inspiration [19]. One of the gamification design implementations is a meta-game reward system, which awards visual indicators for completion of tasks and acts as an overarching game in which players obtain rewards through playing across different games [5]. -

ICIDS18 Program Schedule and Session Info Note on Session Durations

ICIDS18 Program Schedule and Session Info Note on Session Durations: ● Full paper presentations are 25 minutes in duration, including Q+A ● Short paper presentation are 20 minutes in duration, including Q+A ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ WEDNESDAY ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 9:00 AM Registration and Coffee 9:30 AM - 10:45 AM Keynote 1 Research Into Interactive Digital Narrative: A Kaleidoscopic View Janet H. Murray (link to page with photo and bio info: http://homes.lmc.gatech.edu/~murray/) We are at a milestone moment in the development of the cultural form of Interactive Digital Narrative (IDN), and in the development of the study of IDN as a field of academic research and graduate education. We can date the beginning of the field to the late 1960s with the release of Joseph Weizenbaum’s Eliza in 1966, and recognize the late 1990s as another turning point when 30 years of diverse development began to coalesce into a recognizable new media practice. For the past 20 years we have seen accelerated growth in theory and practice, but the discourse has been split among contributory fields. With the convening of IDN as the focus of study in its own right, we can address key questions, such as its distinct history, taxonomy, and aesthetics. We can also recognize more clearly our unique challenges in studying a field that is evolving rapidly, and from multiple intersecting genetic strains. We can also articulate and investigate the potential of IDN as an expressive framework for engaging with the most pressing themes of human culture of the 21st century, and as a cognitive scaffold for increasing our individual and collective understanding of complex systems. -

Established in 1998 Sumthing Else Music Works Is the Industry Leader

SUMTHING ELSE MUSIC WORKS’ SOUNDTRACKS HONORED AT 6TH ANNUAL GAME AUDIO NETWORK GUILD AWARDS Halo 3, Mass Effect, Red Steel Nominated for “Best Original Soundtrack Album” Halo 3 and Mass Effect Nominated for “Audio of the Year” New York – February 7th, 2008 – The Game Audio Network Guild (G.A.N.G.), the non-profit organization dedicated to the advancement and recognition of game audio, recently announced the finalists for the 6th Annual G.A.N.G. Awards to honor outstanding creative, technical and artistic audio achievement in the world of interactive entertainment. Of the 20 entries in the top 4 Award categories, 7 are on the Sumthing Else Music Works (SEMW) Label. These include 3 of the 5 nominees in “Best Original Soundtrack Album” and 2 of the 5 for “Audio of the Year.” Winners will be announced at the 6th Annual G.A.N.G. Awards ceremony being held on Thursday, February 21st, 2008 in San Francisco, CA during the Game Developers Conference. The show will take place in the North Hall of the Moscone Center (Room 134) and will include live video game music performances throughout the evening. SEMW finalists in the 6th Annual G.A.N.G. Awards are highlighted below. AUDIO OF THE YEAR BioShock Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare God of War II Halo 3 Mass Effect MUSIC OF THE YEAR Assassin’s Creed BioShock God of War II Halo 3 The Golden Compass SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR BioShock Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare Crysis The Orange Box Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune BEST ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK ALBUM Dead Head Fred God of War II Halo 3 Mass Effect Red Steel BEST -

Official Fact Sheet in PDF Format

Telltale Games and LucasArts Present ™ Platforms His name is Guybrush Threepwood, and he’s a Mighty Pirate™! This summer, join PC Download him in an all-new monthly series that brings the intrigue, adventure, and rich, WiiWare™ piratey goodness of Monkey Island™ to today’s gamers. Genre Background Episodic Adventure Tales of Monkey Island was created through a partnership between Telltale Games, Comedy the leader in interactive episodic entertainment, and LucasArts, the company that spearheaded the “golden age” of adventure games in the 1990s. Developer Telltale Games The Tales of Monkey Island creative team—also responsible for Telltale’s acclaimed Sam & Max, Strong Bad, and Wallace & Gromit series—includes writers, designers, Publisher and artists who worked on all four of the previous Monkey Island games. Telltale Games The Story ESRB Rating Pending An epic adventure in five parts, Tales of Monkey Island grows more engrossing with each new installment. While battling the evil pirate LeChuck, Guybrush mistakenly Release timeframe unleashes an insidious pox that transforms the buccaneers of the Caribbean into Five monthly episodes unruly monsters. On the Voodoo Lady’s advice, he sets sail in search of La Esponja starting Summer 2009 Grande, a legendary sea sponge that will stem the epidemic. Official website Little does he know, Threepwood’s quest is part of a more sinister plot. Good and www.telltalegames.com/ evil are not always what they seem, and everything you think you know will be monkeyisland challenged as Tales of Monkey Island -

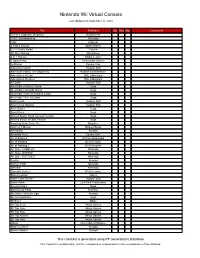

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database.