Tidlige Pianister I Jazzen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Vocal of Frank Foster

1 The TENORSAX of FRANK BENJAMIN FOSTER Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Oct. 7, 2020 2 Born: Cincinnati, Ohio, Sept. 23, 1928 Died: Chesapeake, Virginia, July 26, 2011 Introduction: Oslo Jazz Circle always loved the Count Basie orchestra, no matter what time, and of course we became familiar with Frank Foster’s fine tenorsax playing! Early history: Learned to play saxes and clarinet while in high school. Went to Wilberforce University and left for Detroit in 1949. Played with Wardell Gray until he joined the army in 1951. After his discharge he got a job in Count Basie's orchestra July 1953 after recommendation by Ernie Wilkins. Stayed until 1964. 3 FRANK FOSTER SOLOGRAPHY COUNT BASIE AND HIS ORCHESTRA LA. Aug. 13, 1953 Paul Campbell, Wendell Cully, Reunald Jones, Joe Newman (tp), Johnny Mandel (btp), Henry Coker, Benny Powell (tb), Marshal Royal (cl, as), Ernie Wilkins (as, ts), Frank Wess (fl, ts), Frank Foster (ts), Charlie Fowlkes (bar), Count Basie (p), Freddie Green (g), Eddie Jones (b), Gus Johnson (dm). Three titles were recorded for Clef, two issued, one has FF: 1257-5 Blues Go Away Solo with orch 24 bars. (SM) Frank Foster’s first recorded solo appears when he just has joined the Count Basie organization, of which he should be such an important member for years to come. It is relaxed and highly competent. Hollywood, Aug. 15, 1953 Same personnel. NBC-TV "Hoagy Carmichael Show", three titles, no solo info. Hoagy Carmichael (vo). Pasadena, Sept. 16, 1953 Same personnel. Concert at the Civic Auditorium. Billy Eckstine (vo). -

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail. Cottontail stands as a fine example of Ellington’s “Blanton-Webster” years, where the band was at its peak in performance and popularity. The “Blanton-Webster” moniker refers to bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who recorded Cottontail on May 4th, 1940 alongside Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard, Chauncey Haughton, and Harry Carney on saxophone; Cootie Williams, Wallace Jones, and Ray Nance on trumpet; Rex Stewart on cornet; Juan Tizol, Joe Nanton, and Lawrence Brown on trombone; Fred Guy on guitar, Duke on piano, and Sonny Greer on drums. John Hasse, author of The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, states that Cottontail “opened a window on the future, predicting elements to come in jazz.” Indeed, Jimmy Blanton’s driving quarter-note feel throughout the piece predicts a collective gravitation away from the traditional two feel amongst modern bassists. Webster’s solo on this record is so iconic that audiences would insist on note-for-note renditions of it in live performances. Even now, it stands as a testament to Webster’s mastery of expression, predicting techniques and patterns that John Coltrane would use decades later. Ellington also shows off his Harlem stride credentials in a quick solo before going into an orchestrated sax soli, one of the first of its kind. After a blaring shout chorus, the piece recalls the A section before Harry Carney caps everything off with the droning tonic. Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue. This piece is remarkable for two reasons: Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue exemplifies Duke’s classical influence, and his desire to write more grandiose pieces with more extended forms. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Five Times Daily

Five Times Daily: The Dynamics of Prayer Worship Among Muslim Immigrants in St. John's, NL By Scott Royle A thesis submitted to the Department of Religious Studies at Memorial University of Newfoundland in partial fulfillment for the degree of Masters of Arts in Religious Studies March 2016 Abstract This thesis explores the ritual of prayer among Muslim immigrants in the city of St. John's, NL. Immigration across national, cultural, religious, and ethnic borders is a moment in an individual's life marked by significant change. My premise is that in such contexts the relatively conservative nature of religious ritual can supply much-needed continuity, comfort, and consolation for individuals living- through the immigrant experience. As well, ritual forms are often put under stress when transferred to a considerably different place and cultural context, where “facts on the ground” may be obstacles to traditional and familiar ritual forms. Changes to the understanding or practice of ritual are common in new cultural and geographic situations, and ritual itself often becomes not merely a means of social identification and cohesion, but a practical tool in processing change - in the context of immigration, in learning to live in a new community. St. John's is a lively and historic city and while Muslim immigrants may be a small group within it they nevertheless contribute to the city's energy and atmosphere. This thesis endeavours to better understand the life stories of ten of these newcomers to St. John's, focusing on their religious backgrounds and lives. In particular, this thesis seeks to better understand the place of prayer in the immigrant experience. -

Thad Jones Discography Copy

Thad Jones Discography Compiled by David Demsey 2012-15 Recordings released during Thad Jones’ lifetime, as performer, bandleader, composer/arranger; subsequent CD releases are listed where applicable. Each entry lists Thad Jones compositions/arrangements contained on that recording. Album titles preceded by (•) are contained in the Thad Jones Archive collection. I. As a Leader or Co-Leader Big Band Leader or Co-Leader (chronological): • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Live at the Vanguard (rec. 1/7 [sic], 3/21/66) [live recording donated by George Klabin] Contains: All My Yesterdays (2 versions), Backbone, Big Dipper (2 versions), Mean What You Say, Morning Reverend, Little Pixie, Willow Weep for Me (Brookmeyer), Once Around, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Low Down, Lover Man, Don’t Ever Leave Me, A-That’s Freedom • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, On Tour (rec. varsious dates and locations in Europe) Discs 1-7, 10-11 [see Special Recordings section below] On iTunes. • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, In the Netherlands (rec. 1974) [unreleased live recording donated by John Mosca] • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Presenting the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra (rec. 5/4-5-6/66) Solid State UAL18003 Contains: Balanced Scales = Justice, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Mean What You Say, Once Around, Three and One • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Opening Night (rec. 1[sic]/7/66, incorrect date; released 1990s) Alan Grant / BMG Ct. # 74321519392 Contains: Big Dipper, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Once Around, All My Yesterdays, Morning Reverend, Low Down, Lover Man, Mean What You Say, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Willow Weep for Me (arr. -

Thelonious Monk: Life and Influences Thelonious Monk: Life and Influences

William Hanson Falk Seminar Spring 2008 Thelonious Monk: Life and Influences Thelonious Monk: Life and Influences Thelonious Monk was a prolific and monumental figure in modem jazz. He directly contributed to the evolution of bebop, as well as influenced the development of free jazz, and the contributed additions to the standard jazz repertoire. Monk branched out fiom his influences, including swing, gospel, blues, and classical to create a unique style of composition and performance. Monk more than any other major figure in bebop, was, and remains, an original1 Monk's life can be categorized into three periods: the early, the middle, and late period. Each period lasts roughly twenty years: from 1917- 1940,1940-1960, and from 1960-1982. In Monk's early period he toured the US playing gospel music, and found early influences in swing music like Duke Ellington. It wasn't until his middle period that Monk began to record and write his compositions, and in his late period he toured the world with other renowned musicians playing bebop. Thelonious Junior ~onl?was born October 10,191 7 in Rocky Mountain, North Carolina to Barbara Batts Monk and Thelonious Monk, Senior. Thelonious was the middle child, with an older sister, Marion born in 1915, and younger brother, Thomas born in 1919. Monk's birth certificate lists his father as an ice puller, and his mother as a household worker. Although both of his parents could read and write, they struggled to make enough to live on. In 1922 Thelonious' mother insisted that she take the family to New York to make a better living. -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

John Cornelius Hodges “Johnny” “Rabbit”

1 The ALTOSAX and SOPRANOSAX of JOHN CORNELIUS HODGES “JOHNNY” “RABBIT” Solographers: Jan Evensmo & Ulf Renberg Last update: Aug. 1, 2014, June 5, 2021 2 Born: Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 25, 1906 Died: NYC. May 11, 1970 Introduction: When I joined the Oslo Jazz Circle back in 1950s, there were in fact only three altosaxophonists who really mattered: Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker (in alphabetical order). JH’s playing with Duke Ellington, as well as numerous swing recording sessions made an unforgettable impression on me and my friends. It is time to go through his works and organize a solography! Early history: Played drums and piano, then sax at the age of 14; through his sister, he got to know Sidney Bechet, who gave him lessons. He followed Bechet in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith’s quartet at the Rhythm Club (ca. 1924), then played with Bechet at the Club Basha (1925). Continued to live in Boston during the mid -1920s, travelling to New York for week-end ‘gigs’. Played with Bobby Sawyer (ca. 1925) and Lloyd Scott (ca. 1926), then from late 1926 worked regularly with Chick webb at Paddock Club, Savoy Ballroom, etc. Briefly with Luckey Roberts’ orchestra, then joined Duke Ellington in May 1928. With Duke until March 1951 when formed own small band (ref. John Chilton). Message: No jazz topic has been studied by more people and more systematically than Duke Ellington. So much has been written, culminating with Luciano Massagli & Giovanni M. Volonte: “The New Desor – An updated edition of Duke Ellington’s Story on Records 1924 – 1974”. -

Ernest Elliott

THE RECORDINGS OF ERNEST ELLIOTT An Annotated Tentative Name - Discography ELLIOTT, ‘Sticky’ Ernest: Born Booneville, Missouri, February 1893. Worked with Hank Duncan´s Band in Detroit (1919), moved to New York, worked with Johnny Dunn (1921), etc. Various recordings in the 1920s, including two sessions with Bessie Smith. With Cliff Jackson´s Trio at the Cabin Club, Astoria, New York (1940), with Sammy Stewart´s Band at Joyce´s Manor, New York (1944), in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith´s Band (1947). Has retired from music, but continues to live in New York.” (J. Chilton, Who´s Who of Jazz) STYLISTICS Ernest Elliott seems to be a relict out of archaic jazz times. But he did not spend these early years in New Orleans or touring the South, but he became known playing in Detroit, changing over to New York in the very early 1920s. Thus, his stylistic background is completely different from all those New Orleans players, and has to be estimated in a different way. Bushell in his book “Jazz from the Beginning” says about him: “Those guys had a style of clarinet playing that´s been forgotten. Ernest Elliott had it, Jimmy O´Bryant had it, and Johnny Dodds had it.” TONE Elliott owns a strong, rather sharp, tone on the clarinet. There are instances where I feel tempted to hear Bechet-like qualities in his playing, probably mainly because of the tone. This quality might have caused Clarence Williams to use Elliott when Bechet was not available? He does not hit his notes head-on, but he approaches them with a fast upward slur or smear, and even finishes them mostly with a little downward slur/smear, making his notes to sound sour. -

Fusion Mastering System

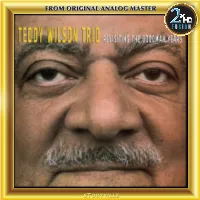

F U S I O N As the jazz century turns, the huge achievements of masters like Teddy Wilson focus up ever more sharply. In Wilson’s case they encompass fifty years in the life of a pianist whose originality has surmounted every trend, both as soloist and as a catalyst for all the greatest musicians of this era. In professions other than music such undiminishing skill and flare would be rewarded with a rich pension, long-service medals, and probably a statue in the main street. But jazz – to its shame – has no mechanism for such honors. So Teddy Wilson continues unobtrusively to prove his royal place in the hierarchy of great jazz pianists by simply going on playing the piano in a way that can never be duplicated and by producing records like this one. Ever since – and perhaps before – Benny Goodman summarized Wilson’s art with the words ‘whatever elegance means, Teddy Wilson is it!’ Jazz text books have typecast his individuality with words like ‘urbane’ ‘polished’, ‘poised’ or ‘impeccable’. Such images though pertinent and well-meant threaten injustice. To begin with, they tell less than half the story, as the rollicking Fats Waller inspired stride piano that introduced ‘What s nigh, what a moon, what a girl’ (with Billie Holliday) told everyone begun to record when I came along’. All three influences forty three years ago. But the real danger is that words had molded into Teddy Wilson by the time he came to like ‘elegant’ are dangerously near the cocktail cabinet Mildred Bailey’s house to jam with Benny Goodman and for a jazz pianist and while Wilson is elegant, he is never Gene Krupa in 1935. -

1 307A Muggsy Spanier and His V-Disk All Stars Riverboat Shuffle 307A Muggsy Spanier and His V-Disk All Stars Shimmy Like My

1 307A Muggsy Spanier And His V-Disk All Stars Riverboat Shuffle 307A Muggsy Spanier And His V-Disk All Stars Shimmy Like My Sister Kate 307B Charlie Barnett and His Orch. Redskin Rhumba (Cherokee) Summer 1944 307B Charlie Barnett and His Orch. Pompton Turnpike Sept. 11, 1944 1 308u Fats Waller & his Rhythm You're Feets Too Big 308u, Hines & his Orch. Jelly Jelly 308u Fats Waller & his Rhythm All That Meat and No Potatoes 1 309u Raymond Scott Tijuana 309u Stan Kenton & his Orch. And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine 309u Raymond Scott In A Magic Garden 1 311A Bob Crosby & his Bob Cars Summertime 311A Harry James And His Orch. Strictly Instrumental 311B Harry James And His Orch. Flight of the Bumble Bee 311B Bob Crosby & his Bob Cars Shortin Bread 1 312A Perry Como Benny Goodman & Orch. Goodbye Sue July-Aug. 1944 1 315u Duke Ellington And His Orch. Things Ain't What They Used To Be Nov. 9, 1943 315u Duke Ellington And His Orch. Ain't Misbehavin' Nov. 9,1943 1 316A kenbrovin kellette I'm forever blowing bubbles 316A martin blanc the trolley song 316B heyman green out of november 316B robin whiting louise 1 324A Red Norvo All Star Sextet Which Switch Is Witch Aug. 14, 1944 324A Red Norvo All Star Sextet When Dream Comes True Aug. 14, 1944 324B Eddie haywood & His Orchestra Begin the Beguine 324B Red Norvo All Star Sextet The bass on the barroom floor 1 325A eddy howard & his orchestra stormy weather 325B fisher roberts goodwin invitation to the blues 325B raye carter dePaul cow cow boogie 325B freddie slack & his orchestra ella mae morse 1 326B Kay Starr Charlie Barnett and His Orch. -

View Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. TOOTS THIELEMANS NEA Jazz Master (2009) Interviewee: Toots Thielemans (April 29, 1922 – August 22, 2016) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 31 and September 1, 2011 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 80 pp. Brown: Today is August 31, 2011. My name is Anthony Brown, and I am conducting the Smithsonian Institution Oral History with NEA Jazz Master, harmonica virtuoso, guitarist and whistler, Toots Thielemans. Hello… Thielemans: Yes, my real name is Jean. Brown: Jean. Thielemans: And in Belgium… I was born in Belgium. Jean-Baptiste Frédéric Isidor. Four first names. And then Thielemans. Brown: That’s funny. Thielemans: And in French-speaking Belgium, they will pronounce it Thielemans. But I was born April 29, 1922. Brown: That’s Duke Ellington’s birthday, as well. Thielemans: Yes. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Brown: All right. Thielemans: Yes, same day. Brown: Yeah, same day. Just a few years later. [laughs] Thielemans: [laughs] Oh, Duke. Okay. Brown: Where in Belgium? What city? Thielemans: In Brussels. Brown: That’s the capitol. Thielemans: In a popular neighborhood of Brussels called Les Marolles. There was… I don’t know, I wouldn’t know which neighborhood to equivalent in New York. Would that be Lower East Side? Or whatever… popular. And my folks, my father and mother, were operating, so to speak, a little beer café—no alcohol but beer, and different beers—in this café on High Street, Rue Haute, on the Marolles.