Warriors, Guardians Or Both: a Grounded Theory Approach Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Anthology

CREATING SPACES 2021 A collection of the winning writings of the 2021 writing competition entitled Creating Spaces: Giving Voice to the Youth of Minnesota Cover Art: Ethan & Kitty Digital Photography by Sirrina Martinez, SMSU alumna Cover Layout: Marcy Olson Assistant Director of Communications & Marketing Southwest Minnesota State University COPYRIGHT © 2021 Creating Spaces: Giving Voice to the Youth of Minnesota is a joint project of Southwest Minnesota State University’s Creative Writing Program and SWWC Service Cooperative. Copyright reverts to authors upon publication. Note to Readers: Some of the works in Creating Spaces may not be appropriate for a younger reading audience. CONTENTS GRADES 3 & 4 Poetry Emma Fosso The Snow on the Trees 11 Norah Siebert A Scribble 12 Teo Winger Juggling 13 Fiction Brekyn Klarenbeek Katy the Super Horse 17 Ryker Gehrke The Journey of Color 20 Penni Moore Friends Forever 35 GRADES 5 & 6 Poetry Royalle Siedschlag Night to Day 39 Addy Dierks When the Sun Hides 40 Madison Gehrke Always a Kid 41 Fiction Lindsey Setrum The Secret Trail 45 Lindsey Setrum The Journey of the Wild 47 Ava Lepp A Change of Heart 52 Nonfiction Addy Dierks Thee Day 59 Brystol Teune My Washington, DC Trip 61 Alexander Betz My Last Week Fishing with my Great Grandpa 65 GRADES 7 & 8 Poetry Brennen Thooft Hoot 69 Kelsey Hinkeldey Discombobulating 70 Madeline Prentice Six-Word Story 71 Fiction Evie Simpson A Dozen Roses 75 Keira DeBoer Life before Death 85 Claire Safranski Asylum 92 Nonfiction Mazzi Moore One Moment Can Pave Your Future -

Interim Report • 1 January – 30 September 2018

THQ NORDIC AB (PUBL) REG NO.: 556582-6558 INTERIM REPORT • 1 JANUARY – 30 SEPTEMBER 2018 EBIT INCREASED 278% TO SEK 90.8 MILLION We had another stable quarter with continued momentum. The strategy of diversification is paying off. Net sales increased by 1,403% to a record SEK 1,272.7 million in the quarter. EBITDA increased by 521% to SEK 214.8 million and EBIT increased by 278% to SEK 90.8 million compared to the same period last year. The gross margin percentage decreased due to a large share of net sales with lower margin within Partner Publishing. Cash flow from operating activities in the quarter was SEK –740.1 million, mainly due to the decision to replace forfaiting of receivables with bank debt within Koch Media. Both THQ Nordic and Koch Media contributed to the group’s EBIT during the quarter. Net sales in the THQ Nordic business area were up 47% to SEK 124.2 million. This was driven by the release of Titan Quest, Red Faction Guerilla Re-Mars-tered and This is the Police 2, in addition to continued performance of Wreckfest. Net sales of Deep Silver were SEK 251.8 million, driven by the release of Dakar 18 and a good performance of Pathfinder Kingmaker at the end of the quarter. The digital net sales of the back-catalogue in both business areas continued to have solid performances. Our Partner Publishing business area had a strong quarter driven by significant releases from our business partners Codemasters, SquareEnix and Sega. During the quarter, we acquired several strong IPs such as Alone in the Dark, Kingdoms of Amalur and Time- splitters. -

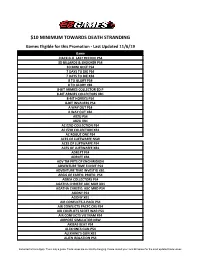

Over 1080 Eligible Titles! Games Eligible for This Promotion - Last Updated 3/14/19 GAME PS4 XB1 NSW .HACK G.U

Over 1080 eligible titles! Games Eligible for this Promotion - Last Updated 3/14/19 GAME PS4 XB1 NSW .HACK G.U. LAST RECODE 1-2-SWITCH 25TH WARD SILVER CASE SE 3D BILLARDS & SNOOKER 3D MINI GOLF 428 SHIBUYA SCRAMBLE 7 DAYS TO DIE 8 TO GLORY 8-BIT ARMIES COLLECTOR ED 8-BIT ARMIES COLLECTORS 8-BIT HORDES 8-BIT INVADERS A PLAGUE TALE A WAY OUT ABZU AC EZIO COLLECTION ACE COMBAT 7 ACES OF LUFTWARE ADR1FT ADV TM PRTS OF ENCHIRIDION ADVENTURE TIME FJ INVT ADVENTURE TIME INVESTIG AEGIS OF EARTH: PROTO AEREA COLLECTORS AGATHA CHRISTIE ABC MUR AGATHA CHRSTIE: ABC MRD AGONY AIR CONFLICTS 2-PACK AIR CONFLICTS DBL PK AIR CONFLICTS PACFC CRS AIR CONFLICTS SECRT WAR AIR CONFLICTS VIETNAM AIR MISSIONS HIND AIRPORT SIMULATOR AKIBAS BEAT ALEKHINES GUN ALEKHINE'S GUN ALIEN ISOLATION AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 AMBULANCE SIMULATOR AMERICAN NINJA WAR Some Restrictions Apply. This is only a guide. Trade values are constantly changing. Please consult your local EB Games for the most updated trade values. Over 1080 eligible titles! Games Eligible for this Promotion - Last Updated 3/14/19 GAME PS4 XB1 NSW AMERICAN NINJA WARRIOR AMONG THE SLEEP ANGRY BIRDS STAR WARS ANIMA: GATE OF MEMORIES ANTHEM AQUA MOTO RACING ARAGAMI ARAGAMI SHADOW ARC OF ALCHEMIST ARCANIA CMPLT TALES ARK ARK PARK ARK SURVIVAL EVOLVED ARMAGALLANT: DECK DSTNY ARMELLO ARMS ARSLAN WARRIORS LGND ASSASSINS CREED 3 REM ASSASSINS CREED CHRONCL ASSASSINS CREED CHRONIC ASSASSINS CREED IV ASSASSINS CREED ODYSSEY ASSASSINS CREED ORIGINS ASSASSINS CREED SYNDICA ASSASSINS CREED SYNDICT ASSAULT SUIT LEYNOS ASSETTO CORSA ASTRO BOT ATELIER FIRIS ATELIER LYDIE & SUELLE ATELIER SOPHIE: ALCHMST ATTACK ON TITAN ATTACK ON TITAN 2 ATV DRIFT AND TRICK ATV DRIFT TRICKS ATV DRIFTS TRICKS ATV RENEGADES AVEN COLONY AXIOM VERGE SE AZURE STRIKER GUNVOLT SP BACK TO THE FUTURE Some Restrictions Apply. -

Cloud Gaming

Cloud Gaming Cristobal Barreto[0000-0002-0005-4880] [email protected] Universidad Cat´olicaNuestra Se~norade la Asunci´on Facultad de Ciencias y Tecnolog´ıa Asunci´on,Paraguay Resumen La nube es un fen´omeno que permite cambiar el modelo de negocios para ofrecer software a los clientes, permitiendo pasar de un modelo en el que se utiliza una licencia para instalar una versi´on"standalone"de alg´un programa o sistema a un modelo que permite ofrecer los mismos como un servicio basado en suscripci´on,a trav´esde alg´uncliente o simplemente el navegador web. A este modelo se le conoce como SaaS (siglas en ingles de Sofware as a Service que significa Software como un Servicio), muchas empresas optan por esta forma de ofrecer software y el mundo del gaming no se queda atr´as.De esta manera surge el GaaS (Gaming as a Servi- ce o Games as a Service que significa Juegos como Servicio), t´erminoque engloba tanto suscripciones o pases para adquirir acceso a librer´ıasde jue- gos, micro-transacciones, juegos en la nube (Cloud Gaming). Este trabajo de investigaci´onse trata de un estado del arte de los juegos en la nube, pasando por los principales modelos que se utilizan para su implementa- ci´ona los problemas que normalmente se presentan al implementarlos y soluciones que se utilizan para estos problemas. Palabras Clave: Cloud Gaming. GaaS. SaaS. Juegos en la nube 1 ´Indice 1. Introducci´on 4 2. Arquitectura 4 2.1. Juegos online . 5 2.2. RR-GaaS . 6 2.2.1. -

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1 Gabriel Huber Jun 05, 2018 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Authentication..............................................3 1.2 Account Management..........................................5 1.3 Listing.................................................. 21 1.4 Store................................................... 25 1.5 Reviews.................................................. 27 1.6 GOG Connect.............................................. 29 1.7 Galaxy APIs............................................... 30 1.8 Game ID List............................................... 45 2 Links 83 3 Contributors 85 HTTP Routing Table 87 i ii GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 Welcome to the unoffical documentation of the APIs used by the GOG website and Galaxy client. It’s a very young project, so don’t be surprised if something is missing. But now get ready for a wild ride into a world where GET and POST don’t mean anything and consistency is a lucky mistake. Contents 1 GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Authentication 1.1.1 Introduction All GOG APIs support token authorization, similar to OAuth2. The web domains www.gog.com, embed.gog.com and some of the Galaxy domains support session cookies too. They both have to be obtained using the GOG login page, because a CAPTCHA may be required to complete the login process. 1.1.2 Auth-Flow 1. Use an embedded browser like WebKit, Gecko or CEF to send the user to https://auth.gog.com/auth. An add-on in your desktop browser should work as well. The exact details about the parameters of this request are described below. 2. Once the login process is completed, the user should be redirected to https://www.gog.com/on_login_success with a login “code” appended at the end. -

THQ Nordic Releases Sine Mora Ex and De Blob

Press release 3 March 2017 THQ Nordic releases Sine Mora Ex and de Blob Karlstad (Sweden), Vienna (Austria), March 3, 2017. In connection with lineup announcement for gamefair PAX East in Boston, THQ Nordic releases two additional new Asset Care products. Sine Mora EX The extended version of the horizontal shoot'em up Sine Mora, providing a unique challenge, where time is the ultimate factor. It is a gorgeous shoot'em up that offers a Story Mode which weaves an over-the-top tale and an Arcade Mode that provides deep, satisfying gameplay to challenge genre fans. Format: PC, Playstation 4 och Xbox One. Digital distribution only. Date: Summer 2017 (Q2/Q3) de Blob Flip, bounce and smash your way past the all-powerful I.N.K.T. Corporation to launch a revolution and save Chroma City from a future without color. Enjoy the 4-player splitscreen multiplayer in eight different modes on different stations. Format: PC, digital distribution. Date: April 27th, 2017 For additional information, please contact: Lars Wingefors, Group CEO Tel: +46 708 471 978 E-post: [email protected] About THQ Nordic THQ Nordic acquires, develops and publishes PC and console games. The core business model consists of acquiring established franchises and successively refining them. The portfolio includes more than 75 franchises such as Darksiders, Titan Quest, MX vs ATV, Red Faction, Destroy All Humans, Aquanox, deBlob, Imperium Galactica, Desperados, Impossible Creatures, Jagged Alliance, Spellforce, The Guild and This is the Police. Since its foundation 2011, the Company has created a global presence, with its Group head office in Karlstad, Sweden and its operational head office in Vienna, Austria. -

Embracer Group Årsredovisning 2019/2020

EMBRACER GROUP ÅRSREDOVISNING 2019/2020 EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) | ÅRSREDOVISNING 2019 / 2020 A INNEHÅLL 2 Årets höjdpunkter 4 Bolagets grundare och VD har ordet 6 Mål och tillväxtstrategi 8 Marknadsöversikt 11 Spelportfölj & Affärsområden 31 Hållbarhetsredovisning 46 Aktien & Bolagsstyrning 59 Årsredovisning & Koncernredovisning 95 Revisionsberättelse 98 Aktieägarinformation FINANSIELL KALENDER Årsstämma 2020 16 september 2020 Delårsrapport, april-september 18 november 2020 Delårsrapport, april-december 18 februari 2021 Bokslutskommuniké 2020/2021 20 maj 2021 Alla uppgifter i denna årsredovisning avser förhållandet vid verksamhetsårets slut, 31 mars 2020 såvida inte annan tid anges. Uppgifterna på sidan 1 avser förhållandet vid tidpunkten för årsredovisningens publicering. B ÅRSREDOVISNING 2019 / 2020 | EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) EMBRACER GROUP I KORTHET USA AUSTRALIEN JAPAN KANADA SYD- KOREA POLEN RYSSLAND SVERIGE FINLAND NORGE BELARUS TYSKLAND NEDERLÄNDERNA FRANKRIKE STORBRITANNIEN SPANIEN PORTUGAL UKRAINA SCHWEIZ BULGARIEN ITALIEN SLOVAKIEN TJECKIEN ÖSTERRIKE MALTA Embracer Group är moderbolag till företag som utvecklar och förlägger PC, konsol- och mobilspel för den globala spelmarknaden. Bolaget har en bred spelportfölj med över 190 ägda varumärken, som till exempel Saints Row, Goat Simulator, Dead Island, Darksiders, Metro, MX vs ATV, Kingdom Come: Deliverance, TimeSplitters, Satisfactory, Wreckfest, Insurgency, Destroy All Humans!, World War Z, SnowRunner och många fler. Koncernen har huvudkontor i Karlstad och global närvaro genom de sex operativa koncernerna: THQ Nordic, Koch Media/Deep Silver, Coffee Stain, Amplifier Game Invest, Saber Interactive och DECA Games. Koncernen har 43 interna studios och fler än 4 000 anställda och kontrakterade medarbetare i fler än 40 länder. Embracer Groups aktier är noterade på Nasdaq First North Stockholm under kortnamnet EMBRAC B. Bolagets Certified Adviser är FNCA Sweden AB. -

Playstation 4 Xbox One Nintendo Switch Pc Game 3Ds

Lista aggiornata al 30/06/2020. Potrebbe subire delle variazioni. Maggiori dettagli in negozio. PLAYSTATION 4 XBOX ONE NINTENDO SWITCH PC GAME 3DS PLAYSTATION 4 11-11 Memories Retold - P4 2Dark - Limited Edition - P4 428 Shibuya Scramble - P4 7 Days to Die - P4 8 To Glory - Bull Riding - P4 A Plague Tale: Innocence - P4 A Way Out - P4 A.O.T. 2 - P4 A.O.T. 2 – Final Battle - P4 A.O.T. Wings of Freedom - P4 ABZÛ - P4 Ace Combat 7 - NON PUBBLICARE - P4 Ace Combat 7 - P4 ACE COMBAT® 7: SKIES UNKNOWN Collector's Edition - P4 Aces of the Luftwaffe - Squadron Extended Edition - P4 Adam’s Venture: Origini - P4 Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Detective - P4 Aerea - Collectors Edition - P4 Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders - P4 Age Of Wonders: Planetfall - Day One Edition - P4 Agents of Mayhem - P4 Agents Of Mayhem - Special Edition - P4 Agony - P4 Air Conflicts Vietnam Ultimate Edition - P4 Alien: Isolation Ripley Edition - P4 Among the Sleep - P4 Angry Birds Star Wars - P4 Anima Gate of Memories: The Nameless Chronicles - P4 Anima: Gate Of Memories - P4 Anthem - Legion of Dawn Edition - P4 Anthem - P4 Apex Construct - P4 Aragami - P4 Arcania - The Complete Tale - P4 ARK Park - P4 ARK: Survival Evolved - Collector's Edition - P4 ARK: Survival Evolved - Explorer Edition - P4 ARK: Survival Evolved - P4 Armello - P4 Arslan The Warriors of Legends - P4 Ash of Gods: Redemption - P4 Assassin’s Creed 4 Black Flag - P4 Assassin's Creed - The Ezio Collection - P4 Assassin's Creed Chronicles - P4 Assassin's Creed III Remastered - P4 Assassin's Creed Odyssey -

Thq Nordic at Full Speed, Net Sales

THQ NORDIC AB (PUBL) REG NO.: 556582-6558 INTERIM REPORT • 1 JANUARY – 31 MARCH 2017 THQ NORDIC AT FULL SPEED, NET SALES INCREASED BY 90% We deliver great results by capitalizing on our portfolio of acquired franchises ac- cording to our business model. There is a great momentum delivering new releases under our asset care program and we had five releases in the first quarter. We are still building up the portfolio of development and in total we had 32 projects ongoing by the end of the quarter. Our first sequels will be finalised and released during the second half of 2017. Our growing publishing team in Vienna is leading the organisation to deliver on our full release schedule for the third and fourth quarter. It will be an intense period of sales, PR, marketing and distribution. After the quarter we announced Darksiders III, a sequel of one of our largest franchises. The feedback from the fans and gaming press have in general been positive. It is de- veloped by parts of the original team of creators at Gunfire Games in Austin. The game is planned to be released during 2018. Financially, we continued to deliver growth and profitability during the first quarter. Net sales increased by 90% to SEK 81.9 m and EBIT increased by 125% to SEK 31.9 m result- ing in an EBIT margin of 39%. This is a great achievement, however, I would like to state that we are still a small player in a large industry. – LARS WINGEFORS, FOUNDER & CEO FIRST QUARTER 2017 > Earnings per share, before and after dilution, > Net sales increased by 90% to SEK 81.9 m (43.1). -

10 MINIMUM TOWARDS DEATH STRANDING Games Eligible for This Promotion - Last Updated 11/6/19 Game .HACK G.U

$10 MINIMUM TOWARDS DEATH STRANDING Games Eligible for this Promotion - Last Updated 11/6/19 Game .HACK G.U. LAST RECODE PS4 3D BILLARDS & SNOOKER PS4 3D MINI GOLF PS4 7 DAYS TO DIE PS4 7 DAYS TO DIE XB1 8 TO GLORY PS4 8 TO GLORY XB1 8-BIT ARMIES COLLECTOR ED P 8-BIT ARMIES COLLECTORS XB1 8-BIT HORDES PS4 8-BIT INVADERS PS4 A WAY OUT PS4 A WAY OUT XB1 ABZU PS4 ABZU XB1 AC EZIO COLLECTION PS4 AC EZIO COLLECTION XB1 AC ROGUE ONE PS4 ACES OF LUFTWAFFE NSW ACES OF LUFTWAFFE PS4 ACES OF LUFTWAFFE XB1 ADR1FT PS4 ADR1FT XB1 ADV TM PRTS OF ENCHIRIDION ADVENTURE TIME FJ INVT PS4 ADVENTURE TIME INVESTIG XB1 AEGIS OF EARTH: PROTO PS4 AEREA COLLECTORS PS4 AGATHA CHRISTIE ABC MUR XB1 AGATHA CHRSTIE: ABC MRD PS4 AGONY PS4 AGONY XB1 AIR CONFLICTS 2-PACK PS4 AIR CONFLICTS PACFC CRS PS4 AIR CONFLICTS SECRT WAR PS4 AIR CONFLICTS VIETNAM PS4 AIRPORT SIMULATOR NSW AKIBAS BEAT PS4 ALEKHINES GUN PS4 ALEKHINE'S GUN XB1 ALIEN ISOLATION PS4 Some Restrictions Apply. This is only a guide. Trade values are constantly changing. Please consult your local EB Games for the most updated trade values. $10 MINIMUM TOWARDS DEATH STRANDING Games Eligible for this Promotion - Last Updated 11/6/19 Game ALIEN ISOLATION XB1 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 PS4 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 XB1 AMERICAN NINJA WAR XB1 AMERICAN NINJA WARRIOR NSW AMERICAN NINJA WARRIOR PS4 AMONG THE SLEEP NSW AMONG THE SLEEP PS4 AMONG THE SLEEP XB1 ANGRY BIRDS STAR WARS PS4 ANGRY BIRDS STAR WARS XB1 ANTHEM PS4 ANTHEM XB1 AQUA MOTO RACING NSW ARAGAMI PS4 ARCANIA CMPLT TALES PS4 ARK PARK PSVR ARK PS4 ARK SURVIVAL EVOLVED -

Embracer Group Annual Report 2019/2020

EMBRACER GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) | ANNUAL REPORT 2019 / 2020 A CONTENTS 2 Highlights of the year 4 Comments by the Founder and CEO 6 Goals and growth strategy 8 Gaming market overview 11 Games Portfolio & Business Areas 31 Sustainability Report 46 The Share & Corporate governance 59 Annual Report & Financial statements 95 Auditor’s Report 98 Shareholder information FINANCIAL CALENDAR Annual General Meeting 2020 16 Sep. 2020 Interim Report, April-September 18 Nov. 2020 Interim Report, April-December 18 Feb. 2021 Full Year Report 2020/2021 20 May 2021 All figures in this report are as per year-end 2019-2020 unless otherwise stated. The information on page 1 refers to the situation at the time of publication of the annual report. B ANNUAL REPORT 2019 / 2020 | EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) EMBRACER GROUP IN BRIEF USA AUSTRALIA JAPAN CANADA SOUTH KOREA POLAND RUSSIA SWEDEN FINLAND NORWAY BELARUS GERMANY NETHERLANDS FRANCE UK SPAIN PORTUGAL UKRAINE SWITZERLAND BULGARIA ITALY SLOVAKIA CZECH REPUBLIC AUSTRIA MALTA Embracer Group is the parent company of businesses developing and publishing PC, console and mobile games for the global games market. The Group has an extensive catalogue of over 190 owned franchises, such as Saints Row, Goat Simulator, Dead Island, Darksiders, Metro, MX vs ATV, Kingdom Come: Deliverance, TimeSplitters, Satisfactory, Wreckfest, Insurgency, Destroy All Humans!, World War Z and SnowRunner, amongst many others. With its head office based in Karlstad, Sweden, Embracer Group has a global presence Annual General Meeting 2020 16 Sep. 2020 through its six operative groups: THQ Nordic, Koch Media/Deep Silver, Coffee Interim Report, April-September 18 Nov. -

New Addition to the THQ Nordic Portfolio

Press release 30 December 2016 New Addition to the THQ Nordic Portfolio THQ Nordic AB Acquires “This is the Police” from Weappy LLC. Karlstad (Sweden), Minsk (Belarus), December 30: Today, THQ Nordic announced that an asset purchase agreement with Weappy LLC has been closed and “This is the Police” is now part of THQ Nordic’s growing IP portfolio. Lars Wingefors, founder and Group CEO, comments: “We are happy to report, that “This is the Police” can now be accounted to our owned IP- and franchise portfolio. Before signing off the asset purchase agreement with Weappy LLC, THQ Nordic functioned as publisher only. In strong cooperation with our friends from Weappy LLC we are working on bringing this exceptional title to current gen consoles and mobile devices which are due for release in 2017.” “This is the Police” is a strategy adventure in a dark but realistic world, which revolves around the gritty Police Chief Jack Boyd with whom you will dive into a deep story of crime and intrigue. The game was released for PC, MAC and Linux on August 2, 2016 and has since then sold more than 165,000 copies. For additional information, please contact: Lars Wingefors, Group CEO Tel: +46 708 471 978 E-post: [email protected] About THQ Nordic THQ Nordic acquires, develops and publishes PC and console games. The core business model consists of acquiring established franchises and successively refining them. The portfolio includes more than 75 franchises such as Darksiders, Titan Quest, MX vs ATV, Red Faction, Destroy All Humans, Aquanox, deBlob, Imperium Galactica, Desperados, Impossible Creatures, Jagged Alliance, Spellforce, The Guild and This is the Police.