Download (1193Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyric Provinces in the English Renaissance

Lyric Provinces in the English Renaissance Harold Toliver LYRIC PROVINCES IN THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Harold Toliver Poets are by no means alone in being pre pared to see new places in settled ways and to describe them in received images. Outer regions will be assimilated into dynasties, never mind the hostility of the natives. The ancient wilderness of the Mediterranean and certain biblical expectations of what burning bushes, gods, and shepherds shall exist every where encroach upon the deserts of Utah and California. Those who travel there see them and other new landscapes in terms of old myths of place and descriptive topoi; and their descriptions take on the structure, to nality, and nomenclature of the past, their language as much recollection as greeting. In Professor Toliver's view, the concern of the literary historian is with, in part, that ever renewed past as it is introduced under the new conditions that poets confront, and is, therefore, with the parallel movement of liter ary and social history. Literature, he reminds us, is inseparable from the rest of discourse (as the study of signs in the past decade has made clearer), but is, nevertheless, distinct from social history in that poets look less to common discourse for their models than to specific literary predecessors. Careful observ ers of place, they seek to bring what is distinct and valuable in it within some sort of verbal compass and relationship with the speaker. They bring with them, however, formulas and tf > w if a loyalty to a cultural heritage that both com plicate and confound the lyric address to place. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

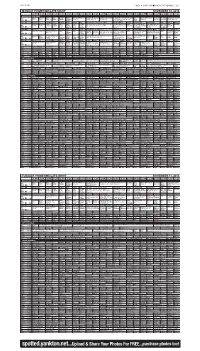

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos For

PAGE 10B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2014 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Arthur Å Wild Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Ice Warriors -- USA Sled Hockey BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) (DVS) Kratts Å Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Miami Beach” Å “Madison” Å The U.S. sled hockey team. (In World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Miami Beach” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å (DVS) News Å KTIV $ 4 $ Queen Latifah Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice The artists perform. (N) Å The Blacklist (N) News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Voice “The Live Playoffs, Night 1” The art- The Blacklist Red and KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å (N) Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Nightly News Bang ists perform. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Berlin head to Moscow. News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % Å Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) Å (In Stereo) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Queen Anne and the Arts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library TRANSITS Queen Anne and the Arts EDITED BY CEDRIC D. REVERAND II LEWISBURG BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS 14_461_Reverand.indb 5 9/22/14 11:19 AM Published by Bucknell University Press Copublished by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannery Street, London SE11 4AB All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data <insert CIP data> ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America 14_461_Reverand.indb 6 9/22/14 11:19 AM CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1 “Praise the Patroness of Arts” 7 James A. Winn 2 “She Will Not Be That Tyrant They Desire”: Daniel Defoe and Queen Anne 35 Nicholas Seager 3 Queen Anne, Patron of Poets? 51 Juan Christian Pellicer 4 The Moral in the Material: Numismatics and Identity in Evelyn, Addison, and Pope 59 Barbara M. Benedict 5 Mild Mockery: Queen Anne’s Era and the Cacophony of Calm 79 Kevin L. -

Country Carpet

PAGE SIX-BFOUR-B TTHURSDAYHURSDAY, ,F AEBRUARYUGUST 23, 2, 20122012 THE LICKING VALLEYALLEY COURIER Stop By Speedy Your Feed Frederick & May Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurnitureCash SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New & Used Furniture & AppliancesCheck Specialists NeedsFrederick With A Line& May Of QUALITY FrigidaireFor All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! 22.6 Cubic Feet Advance QUALITYFEED RefrigerationAppliances. Needs With A iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! $ 00 •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. We hold all customer Regular FOR ALL Remember We 999 •Superior Design and Quality • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends Need Cash? Checks for 30 days! Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FORYOUR ALL ServiceRemember What We We Service Sell! 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control •• All Animal Popular Health Brands Products • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOURFARM $ 00 $379 •• Animal Pet Food Health & Supplies Products •Horse Tack What We Sell! Speedy Cash •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms •• Pet Farm Food & Garden & Supplies Supplies •Horse Tack ANIMALSFARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty •• FarmPlus Ole & GardenYeller Dog Supplies Food Frederick & May Brentny Cantrell •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May 1209 West Main St. No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty Lumber Co., Inc. West Liberty, KY 41472 ALLAN’S TIRE SUPPLY, INC. Lyon(Moved Feed To New Location of West Behind Save•A•Lot)Liberty 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. -

Primetime • Tuesday, April 17, 2012 Early Morning

Section C, Page 4 THE TIMES LEADER—Princeton, Ky.—April 14, 2012 PRIMETIME • TUESDAY, APRIL 17, 2012 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 ^ 9 Eyewitness News Who Wants to Be a Last Man Standing (7:31) Cougar Town Dancing With the Stars (N) (S) (Live) (9:01) Private Practice Erica’s medical Eyewitness News Nightline (N) (CC) (10:55) Jimmy Kimmel Live “Dancing WEHT at 6pm (N) (CC) Millionaire (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (CC) condition gets worse. (N) (CC) at 10pm (N) (CC) With the Stars”; Ashanti. (N) (CC) # # News (N) (CC) Entertainment To- Last Man Standing (7:31) Cougar Town Dancing With the Stars (N) (S) (Live) (9:01) Private Practice Erica’s medical News (N) (CC) (10:35) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live “Dancing With the WSIL night (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (CC) condition gets worse. (N) (CC) (N) (CC) Stars”; Ashanti. (N) (CC) $ $ Channel 4 News at Channel 4 News at The Biggest Loser The contestants re- The Voice “Live Eliminations” Vocalists Fashion Star “Out of the Box” The design- Channel 4 News at (10:35) The Tonight Show With Jay (11:37) Late Night WSMV 6pm (N) (CC) 6:30pm (N) (CC) view their progress. (N) (CC) face elimination. (N) (S) (Live) (CC) ers push creative boundaries. (N) 10pm (N) (CC) Leno (CC) With Jimmy Fallon % % Newschannel 5 at 6PM (N) (CC) NCIS “Rekindled” The team investigates a NCIS: Los Angeles “Lone Wolf” A discov- Unforgettable “Trajectories” A second NewsChannel 5 at (10:35) Late Show With David Letter- Late Late Show/ WTVF warehouse fire. -

![The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3600/the-history-of-king-lear-1681-lear-as-inscriptive-site-john-rempel-1643600.webp)

The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel

Document generated on 09/29/2021 12:39 a.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site John Rempel Theatre of the world Théâtre du monde Volume 17, 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1012380ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rempel, J. (1998). Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site. Lumen, 17, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar Copyright © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 1998 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3. Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site From Addison in 1711 ('as it is reformed according to the chimerical notion of poetical justice, in my humble opinion it has lost half its beauty') to Michael Dobson in 1992 (Shakespeare 'serves for Tate .. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Gibbs's Rules

Gibbs's Rules THIS SITE USES COOKIES Gibbs's Rules are an extensive series of guidelines that NCIS Special Agent Leroy Jethro Gibbs lives by and teaches to the people he works closely with. FANDOM and our partners use technology such as cookies on our site to personalize content and ads, provide social media features, and analyze our traffic. In particular, we want to draw your attention to cookies which are used to market to you, or provide personalized ads to you. Where we use these cookies (“advertising cookies”), we do so only where you have consented to our use of such cookies by ticking Contents [show] "ACCEPT ADVERTISING COOKIES" below. Note that if you select reject, you may see ads that are less relevant to you and certain features of the site may not work as intended. You can change your mind and revisit your consent choices at any time by visiting our privacy policy. For more information about the cookies we use, please see our Privacy Policy. For information about our partners using advertising cookies on our site, please see the Partner List below. Origins It was revealed in the last few minutes of the Season 6 episode, Heartland (episode) that Gibbs's rules originated from his first AwCifCeE, SPhTa AnDnVoEn RGTibISbIsN,G w CheOrOeK sIhEeS told him at their first meeting that "Everyone needs a code they can live by". The only rule of Shannon's personal code that is quoted is either her first or third: "Never date a lumberjack." REJECT ADVERTISING COOKIES Years later, after their wedding, Gibbs began writing his rules down, keeping them in a small tin inside his home which was shown in the Season 7 finale episode, Rule Fifty-One (episode). -

Super! Drama TV June 2021 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-6:00 on the 10Th

Super! drama TV June 2021 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-6:00 on the 10th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.05.31 2021.06.01 2021.06.02 2021.06.03 2021.06.04 2021.06.05 2021.06.06 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 06:00 00 00 00 00 06:00 00 00 06:00 STINGRAY #27 STINGRAY #29 STINGRAY #31 STINGRAY #33 STINGRAY #35 STINGRAY #37 『DEEP HEAT』 『TITAN GOES POP』 『TUNE OF DANGER』 『THE COOL CAVE MAN』 『TRAPPED IN THE DEPTHS』 『A CHRISTMAS TO REMEMBER』 06:30 30 30 30 30 06:30 30 30 06:30 STINGRAY #28 STINGRAY #30 STINGRAY #32 STINGRAY #34 STINGRAY #36 STINGRAY #38 『IN SEARCH OF THE TAJMANON』 『SET SAIL FOR ADVENTURE』 『RESCUE FROM THE SKIES』 『A NUT FOR MARINEVILLE』 『EASTERN ECLIPSE』 『THE LIGHTHOUSE DWELLERS』 07:00 00 00 00 00 07:00 00 00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #19 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #20 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #21 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 11 #22 STAR TREK Season 1 #29 INSTINCT #5 『Tribute』 『Inner Beauty』 『Devil's Backbone』 『The Storm』 『Operation -- Annihilate!』 『Heartless』 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 00 00 00 00 08:00 00 00 08:00 MACGYVER Season 2 #12 MACGYVER Season 2 #13 MACGYVER Season 2 #14 MACGYVER Season 2 #15 MANHUNT: DEADLY GAMES #2 INSTINCT #6 『Mac + Jack』 『Co2 Sensor + Tree Branch』 『Mardi Gras Beads + Chair』 『Murdoc + Handcuffs』 『Unabubba』 『Flat Line』 08:30 08:30 08:30 09:00 00 00 00 00 09:00 00 00 09:00 information [J] information [J] information [J] information [J] information [J] information [J] 09:30 30 30 30 30 09:30 30 30 09:30 ZOEY'S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST MANHUNT: -

Nahum Tate's Richard II and the Late Stuart Succession Crisis

Nahum Tate’s Richard II and the Late Stuart Succession Crisis Professor Paulina Kewes in conversation with Dr Joseph Hone www.stuarts-online.com Joseph Hone: I'm sitting here in the Bodleian Library with Professor Paulina Kewes, and we’re looking at some plays from the Restoration, particularly adaptations of Shakespeare made after the Restoration. Now, Paulina, why exactly did these Restoration playwrights turn to Shakespeare and adapt his plays for their audiences? Paulina Kewes: Theatres reopened in 1660 after an eighteen year hiatus, and there was a huge demand for new plays. obviously there were no playwrights because there had been no theatres before. so there was push to adapt older plays in order to make them effective on the new stage. And there were three key requirements: (a) to have more parts for women, because this is the first time when we have actresses. Secondly, to take advantage of movable scenery which again appeared for the first time. And, thirdly, to take advantage of special effects of machines. So just to give you an example: Macbeth adapted by having more parts for women. In addition to Lady Macbeth we have a larger part for Lady Macduff, and more witches. The witches are now flying across the stage. But adapting Shakespeare also gave the opportunity to play right to address political themes. Immediately after the Restoration, early after the Restoration, we have for example a version of the Tempest which revisits the themes of rebellion and regicide in the tragicomic mode whilst also adding more parts for women.