Paul Halmos: in His Own Words John Ewing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alfred Tarski and a Watershed Meeting in Logic: Cornell, 1957 Solomon Feferman1

Alfred Tarski and a watershed meeting in logic: Cornell, 1957 Solomon Feferman1 For Jan Wolenski, on the occasion of his 60th birthday2 In the summer of 1957 at Cornell University the first of a cavalcade of large-scale meetings partially or completely devoted to logic took place--the five-week long Summer Institute for Symbolic Logic. That meeting turned out to be a watershed event in the development of logic: it was unique in bringing together for such an extended period researchers at every level in all parts of the subject, and the synergetic connections established there would thenceforth change the face of mathematical logic both qualitatively and quantitatively. Prior to the Cornell meeting there had been nothing remotely like it for logicians. Previously, with the growing importance in the twentieth century of their subject both in mathematics and philosophy, it had been natural for many of the broadly representative meetings of mathematicians and of philosophers to include lectures by logicians or even have special sections devoted to logic. Only with the establishment of the Association for Symbolic Logic in 1936 did logicians begin to meet regularly by themselves, but until the 1950s these occasions were usually relatively short in duration, never more than a day or two. Alfred Tarski was one of the principal organizers of the Cornell institute and of some of the major meetings to follow on its heels. Before the outbreak of World War II, outside of Poland Tarski had primarily been involved in several Unity of Science Congresses, including the first, in Paris in 1935, and the fifth, at Harvard in September, 1939. -

UTM Naive Lie Theory (John Stillwell) 0387782141.Pdf

Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics Editors S. Axler K.A. Ribet Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics Abbott: Understanding Analysis. Daepp/Gorkin: Reading, Writing, and Proving: Anglin: Mathematics: A Concise History and A Closer Look at Mathematics. Philosophy. Devlin: The Joy of Sets: Fundamentals Readings in Mathematics. of-Contemporary Set Theory. Second edition. Anglin/Lambek: The Heritage of Thales. Dixmier: General Topology. Readings in Mathematics. Driver: Why Math? Apostol: Introduction to Analytic Number Theory. Ebbinghaus/Flum/Thomas: Mathematical Logic. Second edition. Second edition. Armstrong: Basic Topology. Edgar: Measure, Topology, and Fractal Geometry. Armstrong: Groups and Symmetry. Second edition. Axler: Linear Algebra Done Right. Second edition. Elaydi: An Introduction to Difference Equations. Beardon: Limits: A New Approach to Real Third edition. Analysis. Erdos/Sur˜ anyi:´ Topics in the Theory of Numbers. Bak/Newman: Complex Analysis. Second edition. Estep: Practical Analysis on One Variable. Banchoff/Wermer: Linear Algebra Through Exner: An Accompaniment to Higher Mathematics. Geometry. Second edition. Exner: Inside Calculus. Beck/Robins: Computing the Continuous Fine/Rosenberger: The Fundamental Theory Discretely of Algebra. Berberian: A First Course in Real Analysis. Fischer: Intermediate Real Analysis. Bix: Conics and Cubics: A Concrete Introduction to Flanigan/Kazdan: Calculus Two: Linear and Algebraic Curves. Second edition. Nonlinear Functions. Second edition. Bremaud:` An Introduction to Probabilistic Fleming: Functions of Several Variables. Second Modeling. edition. Bressoud: Factorization and Primality Testing. Foulds: Combinatorial Optimization for Bressoud: Second Year Calculus. Undergraduates. Readings in Mathematics. Foulds: Optimization Techniques: An Introduction. Brickman: Mathematical Introduction to Linear Franklin: Methods of Mathematical Programming and Game Theory. Economics. Browder: Mathematical Analysis: An Introduction. Frazier: An Introduction to Wavelets Through Buchmann: Introduction to Cryptography. -

Paul Erdős Mathematical Genius, Human (In That Order)

Paul Erdős Mathematical Genius, Human (In That Order) By Joshua Hill MATH 341-01 4 June 2004 "A Mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent that theirs, it is because the are made with ideas... The mathematician's patterns, like the painter's or the poet's, must be beautiful; the ideas, like the colours of the words, must fit together in a harmonious way. Beauty is the first test: there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics." --G.H. Hardy "Why are numbers beautiful? It's like asking why is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony beautiful. If you don't see why, someone can't tell you. I know numbers are beautiful. If they aren't beautiful, nothing is." -- Paul Erdős "One of the first people I met in Princeton was Paul Erdős. He was 26 years old at the time, and had his Ph.D. for several years, and had been bouncing from one postdoctoral fellowship to another... Though I was slightly younger, I considered myself wiser in the ways of the world, and I lectured Erdős "This fellowship business is all well and good, but it can't go on for much longer -- jobs are hard to get -- you had better get on the ball and start looking for a real honest job." ... Forty years after my sermon, Erdős hasn't found it necessary to look for an "honest" job yet." -- Paul Halmos Introduction Paul Erdős (said "Air-daish") was a brilliant and prolific mathematician, who was central to the advancement of several major branches of mathematics. -

February 2003 FOCUS Major Donation Announced for New MAA Conference Center

FOCUS February 2003 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January, February, March, April, May/June, FOCUS August/September, October, November, and December. February 2003 Editor: Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College; [email protected] Volume 23, Number 2 Managing Editor: Carol Baxter, MAA [email protected] Senior Writer: Harry Waldman, MAA Inside [email protected] Please address advertising inquiries to: Carol Baxter, MAA; [email protected] 3Major Donation Announced for New MAA Conference Center President: Ronald L. Graham By G. L. Alexanderson First Vice-President: Carl C. Cowen, Second Vice-President: Joseph A. Gallian, Secretary: 6So You Think You Want to be in Pictures… Martha J. Siegel, Associate Secretary: James By Dan Rockmore J. Tattersall, Treasurer: John W. Kenelly Executive Director: Tina H. Straley 8 The Kentucky Section Goes High-Tech: The tale of an e-newsletter Associate Executive Director and Director By Alex McAllister of Publications and Electronic Services: Donald J. Albers 10 Biology and Mathematics FOCUS Editorial Board: Gerald By Victor Katz Alexanderson; Donna Beers; J. Kevin Colligan; Ed Dubinsky; Bill Hawkins; Dan Kalman; Peter Renz; Annie Selden; Jon Scott; 14 Statistical Based Evidence that Web-Based Homework Helps Ravi Vakil. By L. Hirsch and C. Weibel Letters to the editor should be addressed to Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College, Dept. of 15 Short Takes Mathematics, Waterville, ME 04901, or by email to [email protected]. 16 Contributed Paper Sessions for MathFest 2003 Subscription and membership questions should be directed to the MAA Customer Service Center, 800-331-1622; e-mail: 20 MAA Awards Announced at Baltimore Joint Meetings [email protected]; (301) 617-7800 (outside U.S. -

FOCUS August/September 2005

FOCUS August/September 2005 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January, February, March, April, May/June, FOCUS August/September, October, November, and Volume 25 Issue 6 December. Editor: Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College; [email protected] Inside Managing Editor: Carol Baxter, MAA 4 Saunders Mac Lane, 1909-2005 [email protected] By John MacDonald Senior Writer: Harry Waldman, MAA [email protected] 5 Encountering Saunders Mac Lane By David Eisenbud Please address advertising inquiries to: Rebecca Hall [email protected] 8George B. Dantzig 1914–2005 President: Carl C. Cowen By Don Albers First Vice-President: Barbara T. Faires, 11 Convergence: Mathematics, History, and Teaching Second Vice-President: Jean Bee Chan, An Invitation and Call for Papers Secretary: Martha J. Siegel, Associate By Victor Katz Secretary: James J. Tattersall, Treasurer: John W. Kenelly 12 What I Learned From…Project NExT By Dave Perkins Executive Director: Tina H. Straley 14 The Preparation of Mathematics Teachers: A British View Part II Associate Executive Director and Director By Peter Ruane of Publications: Donald J. Albers FOCUS Editorial Board: Rob Bradley; J. 18 So You Want to be a Teacher Kevin Colligan; Sharon Cutler Ross; Joe By Jacqueline Brennon Giles Gallian; Jackie Giles; Maeve McCarthy; Colm 19 U.S.A. Mathematical Olympiad Winners Honored Mulcahy; Peter Renz; Annie Selden; Hortensia Soto-Johnson; Ravi Vakil. 20 Math Youth Days at the Ballpark Letters to the editor should be addressed to By Gene Abrams Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College, Dept. of 22 The Fundamental Theorem of ________________ Mathematics, Waterville, ME 04901, or by email to [email protected]. -

I Want to Be a Mathematician: a Conversation with Paul Halmos

I Want to Be a Mathematician: A Conversation with Paul Halmos Reviewed by John Ewing I Want to Be a Mathematician: A Conversation social, professional, with Paul Halmos family, friends, and A film by George Csicsery travel. Mathematical Association of America, 2009 In a bygone DVD: US$39.95 List; $29.95 Member of MAA age, this was not ISBN-978-0-88385-909-4 unusual. Some decades ago, the annual meeting of the American I spent most of a lifetime trying to be a Mathematical So- mathematician—and what did I learn? ciety was held in What does it take to be one? I think I the period between know the answer: you have to be born Christmas and New right, you must continually strive to Year’s. Stories tell become perfect, you must love math- of mathematicians ematics more than anything else, you who packed up their must work at it hard and without stop, families and drove halfway across the country to and you must never give up. attend that meeting as a perfectly ordinary way to celebrate the holidays. Decades later, summer —Paul Halmos, I Want to Be a Math- meetings of the AMS/MAA (and then only the ematician: An Automathography in MAA) were events to which families tagged along Three Parts, Mathematical Association to join up with other mathematical families for of America, Washington, 1988, p. 400 a summer vacation…at a mathematics meeting! Social life in mathematics departments revolved What does it mean to be a mathematician? That’s around colloquia and seminar dinners, as well as not a fashionable question these days. -

An Interview with Martin Davis

Notices of the American Mathematical Society ISSN 0002-9920 ABCD springer.com New and Noteworthy from Springer Geometry Ramanujan‘s Lost Notebook An Introduction to Mathematical of the American Mathematical Society Selected Topics in Plane and Solid Part II Cryptography May 2008 Volume 55, Number 5 Geometry G. E. Andrews, Penn State University, University J. Hoffstein, J. Pipher, J. Silverman, Brown J. Aarts, Delft University of Technology, Park, PA, USA; B. C. Berndt, University of Illinois University, Providence, RI, USA Mediamatics, The Netherlands at Urbana, IL, USA This self-contained introduction to modern This is a book on Euclidean geometry that covers The “lost notebook” contains considerable cryptography emphasizes the mathematics the standard material in a completely new way, material on mock theta functions—undoubtedly behind the theory of public key cryptosystems while also introducing a number of new topics emanating from the last year of Ramanujan’s life. and digital signature schemes. The book focuses Interview with Martin Davis that would be suitable as a junior-senior level It should be emphasized that the material on on these key topics while developing the undergraduate textbook. The author does not mock theta functions is perhaps Ramanujan’s mathematical tools needed for the construction page 560 begin in the traditional manner with abstract deepest work more than half of the material in and security analysis of diverse cryptosystems. geometric axioms. Instead, he assumes the real the book is on q- series, including mock theta Only basic linear algebra is required of the numbers, and begins his treatment by functions; the remaining part deals with theta reader; techniques from algebra, number theory, introducing such modern concepts as a metric function identities, modular equations, and probability are introduced and developed as space, vector space notation, and groups, and incomplete elliptic integrals of the first kind and required. -

The Geometry Center Reaches

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MA THEMA TICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA The Geometry Center Reaches Out Volume IS, Number 1 A major mission of the NSF-sponsored University of Minnesota Geometry Center is to support, develop, and promote the communication of mathematics at all levels. Last year, the center increased its efforts to reach and to educate diffe rent and dive rse groups ofpeople about the beauty and utility of mathematics. Center members Harvey Keynes and Frederick J. Wicklin describe In this Issue some recent efforts to reach the general public, professional mathematicians, high school teach ers, talented youth, and underrepresented groups in mathematics. 3 MAA President's Column Museum Mathematics Just a few years ago, a trip to the local 7 Mathematics science museum resembled a visit to Awareness Week a taxidermy shop. The halls of the science museum displayed birds of 8 Highlights from prey, bears, cougars, and moose-all stiff, stuffed, mounted on pedestals, the Joint and accompanied by "Don't Touch" Mathematics signs. The exhibits conveyed to all Meetings visitors that science was rigid, bor ing, and hardly accessible to the gen 14 NewGRE eral public. Mathematical Fortunately times have changed. To Reasoning Test day even small science museums lit erally snap, crackle, and pop with The graphical interface to a museum exhibit that allows visitors to interactive demonstrations of the explore regular polyhedra and symmetries. 20 Letters to the physics of electricity, light, and sound. Editor Visitors are encouraged to pedal, pump, and very young children to adults, so it is accessible push their way through the exhibit hall. -

The I Nstitute L E T T E R

THE I NSTITUTE L E T T E R INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY · FALL 2004 ARNOLD LEVINE APPOINTED FACULTY MEMBER IN THE SCHOOL OF NATURAL SCIENCES he Institute for Advanced Study has announced the appointment of Arnold J. Professor in the Life Sciences until 1998. TLevine as professor of molecular biology in the School of Natural Sciences. Profes- He was on the faculty of the Biochemistry sor Levine was formerly a visiting professor in the School of Natural Sciences where he Department at Princeton University from established the Center for Systems Biology (see page 4). “We are delighted to welcome 1968 to 1979, when he became chair and to the Faculty of the Institute a scientist who has made such notable contributions to professor in the Department of Microbi- both basic and applied biological research. Under Professor Levine’s leadership, the ology at the State University of New York Center for Systems Biology will continue working in close collaboration with the Can- at Stony Brook, School of Medicine. cer Institute of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Lewis-Sigler Center The recipient of many honors, among for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University, and BioMaPS Institute at Rutgers, his most recent are: the Medal for Out- The State University of New Jersey, as well as such industrial partners as IBM, Siemens standing Contributions to Biomedical Corporate Research, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck & Co.,” commented Peter Research from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Goddard, Director of the Institute. Cancer Center (2000); the Keio Medical Arnold J. Levine’s research has centered on the causes of cancer in humans and ani- Science Prize of the Keio University mals. -

Scientific Workplace· • Mathematical Word Processing • LATEX Typesetting Scientific Word· • Computer Algebra

Scientific WorkPlace· • Mathematical Word Processing • LATEX Typesetting Scientific Word· • Computer Algebra (-l +lr,:znt:,-1 + 2r) ,..,_' '"""""Ke~r~UrN- r o~ r PooiliorK 1.931'J1 Po6'lf ·1.:1l26!.1 Pod:iDnZ 3.881()2 UfW'IICI(JI)( -2.801~ ""'"""U!NecteoZ l!l!iS'11 v~ 0.7815399 Animated plots ln spherical coordln1tes > To make an anlm.ted plot In spherical coordinates 1. Type an expression In thr.. variables . 2 WMh the Insertion poilt In the expression, choose Plot 3D The next exampfe shows a sphere that grows ftom radius 1 to .. Plot 3D Animated + Spherical The Gold Standard for Mathematical Publishing Scientific WorkPlace and Scientific Word Version 5.5 make writing, sharing, and doing mathematics easier. You compose and edit your documents directly on the screen, without having to think in a programming language. A click of a button allows you to typeset your documents in LAT£X. You choose to print with or without LATEX typesetting, or publish on the web. Scientific WorkPlace and Scientific Word enable both professionals and support staff to produce stunning books and articles. Also, the integrated computer algebra system in Scientific WorkPlace enables you to solve and plot equations, animate 20 and 30 plots, rotate, move, and fly through 3D plots, create 3D implicit plots, and more. MuPAD' Pro MuPAD Pro is an integrated and open mathematical problem solving environment for symbolic and numeric computing. Visit our website for details. cK.ichan SOFTWARE , I NC. Visit our website for free trial versions of all our products. www.mackichan.com/notices • Email: info@mac kichan.com • Toll free: 877-724-9673 It@\ A I M S \W ELEGRONIC EDITORIAL BOARD http://www.math.psu.edu/era/ Managing Editors: This electronic-only journal publishes research announcements (up to about 10 Keith Burns journal pages) of significant advances in all branches of mathematics. -

Maria Asikainen Monologi

PROCEEDINGS OF THE ELDER CHRONICLERS OF ARCHAIC FOLKLORE, EDITION ROOTORIT OTE ARVONIMIKOMITEAN SALAISESTA LISÄPÖYTÄKIRJASTA KUNNIANARVOISALLE LOGARITMILLE MARIA ASIKAINEN TÄTEN LUOVUTETAAN ARVONIMI MONOLOGI JONKA HYÖDYNTÄMISEEN, VÄÄRIN- JA OIKEINKÄYTTÖÖN NIMETTÄVÄLLÄ ON TÄYSI VELVOLLISUUS Ikuisen Rauhan ja Arvokkuuden Päivölän Kansanopiston Päivölän Sosialististen Matematiikkalinjan Vanhempi Matematiikkalinjojen Vuosikurssi Rootorit Aksiomaattinen Maailmanliitto Rootorit Päivölä Math School Päivölän kansanopisto Seuraava Maailma Päivöläntie 52, 37770 Tarttila Abstract. Kyseinen logaritmi on Päivölän kuulu puhelahjoistaan. Key words: logaritmi, eksponenttifunktio, arvonimi, sakke, päivölä, matematiikka, hi- naus, roottorit, voitto, ohi on, ei ole, enään 1 Loremipsum * Mathematicians generally understand both "ln(x)"and "log(x)"to mean loge(x) and write "log10(x)"when the base-10 logarithm of x is intended. Calculus textbooks will occasionally write "lg(x)"to represent "log10(x)". * Many engineers, biologists, astronomers, and some others write only "ln(x)"or "lo- ge(x)"when they mean the natural logarithm of x, and take "log(x)"to mean log10(x) or, sometimes in the context of computing, log2(x). 1 PROCEEDINGS OF THE ELDER CHRONICLERS OF ARCHAIC FOLKLORE, EDITION ROOTORIT * On most calculators, the LOG button is log10(x) and LN is loge(x). * In most commonly used computer programming languages, including C, C++, Java, Fortran, Ruby, and BASIC, the "log"function returns the natural logarithm. The base-10 function, if it is available, is generally "log10." * Some people use Log(x) (capital L) to mean log10(x), and use log(x) with a lowerca- se l to mean loge(x). * The notation Log(x) is also used by mathematicians to denote the principal branch of the (natural) logarithm function. -

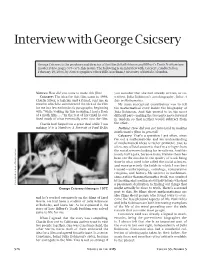

Interview with George Csicsery

Interview with George Csicsery George Csicsery is the producer and director of the film Julia Robinson and Hilbert’s Tenth Problem (see movie review, pages 573–575, this issue). The following is an interview with Csicsery, conducted on February 19, 2008, by Notices graphics editor Bill Casselman, University of British Columbia. Notices: How did you come to make this film? you consider that she had already written, or co- Csicsery: The idea for this film came in 1998. written, Julia Robinson’s autobiography, Julia: A Charlie Silver, a logician and a friend, sent me an Life in Mathematics. email in which he summarized the idea of the film My main conceptual contribution was to tell for me in a few enthusiastic paragraphs, beginning the mathematical story inside the biography of with “While waking up this morning, I had a flash Julia Robinson. And this proved to be the most of a math film … .” In the rest of his email he out- difficult part—making the two parts move forward lined much of what eventually went into the film. in tandem so that neither would subtract from Charlie had helped me a great deal while I was the other. making N is a Number: A Portrait of Paul Erd˝so , Notices: How did you get interested in making mathematics films in general? Csicsery: That’s a question I get often, since I’m not a mathematician and my understanding of mathematical ideas is rather primitive. Just as often, my official answer is that I’m a refugee from the social sciences looking for terra firma.