Tideline Winter04 Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marin Islands NWR Sport Fishing Plan

Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 MARIN ISLANDS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE 3 SPORT FISHING PLAN 3 1. Introduction 3 2. Statement of Objectives 4 3. Description of the Fishing Program 5 A. Area to be Opened to Fishing 5 B. Species to be Taken, Fishing periods, Fishing Access 5 C. Fishing Permit Requirements 7 D. Consultation and Coordination with the State 7 E. Law Enforcement 7 F. Funding and Staffing Requirements 8 4. Conduct of the Fishing Program 8 A. Permit Application, Selection, and/or Registration Procedures (if applicable) 8 B. Refuge-Spec if ic Fishing Regulat ions 8 C. Relevant State Regulations 8 D. Other Refuge Rules and Regulations for Sport Fishing 8 5. Public Engagement 9 A. Outreach for Announcing and Publicizing the Fishing Program 9 B. Anticipated Public Reaction to the Fishing Program 9 C. How Anglers Will Be Informed of Relevant Rules and Regulations 9 6. Compatibility Determination 9 7. Literature Cited 9 List of Figures Figure 1. Proposed Sport Fishing Area Fishing…………………………………6 Marin Islands NWR Fishing Plan Page 2 MARIN ISLANDS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SPORT FISHING PLAN 1. Introduction National Wildlife Refuges are guided by the mission and goals of the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS), the purposes of an individual refuge, Service policy, and laws and international treaties. Relevant guidance includes the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966, as amended by the National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997, Refuge Recreation Act of 1962, and selected portions of the Code of Federal Regulations and Fish and Wildlife Service Manual. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is twofold: to provide general information for anyone interested in the California islands and to serve as a field guide for visitors to the islands. The book covers both general history and nat- ural history, from the geological origins of the islands through their aboriginal inhabitants and their marine and terrestrial biotas. Detailed coverage of the flora and fauna of one island alone would completely fill a book of this size; hence only the most common, most readily observed, and most interesting species are included. The names used for the plants and animals discussed in this book are the most up-to-date ones available, based on the scientific literature and the most recently published guidebooks. Common names are always subject to local variations, and they change constantly. Where two names are in common use, they are both mentioned the first time the organism is discussed. Ironically, in recent years scientific names have changed more recently than common names, and the reader concerned about a possible discrepancy in nomenclature should consult the scientific literature. If a significant nomenclatural change has escaped our notice, we apologize. For plants, our primary reference has been The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, edited by James C. Hickman, including the latest lists of errata. Variation from the nomenclature in that volume is due to more recent interpretations, as explained in the text. Certain abbreviations used throughout the text may not be immedi- ately familiar to the general reader; they are as follows: sp., species (sin- gular); spp., species (plural); n. -

San Pablo Bay and Marin Islands National Wildlife Refuges - Refuges in the North Bay by Bryan Winton

San Pablo Bay NWR Tideline Newsletter Archives San Pablo Bay and Marin Islands National Wildlife Refuges - Refuges in the North Bay by Bryan Winton Editor’s Note: In March 2003, the National Wildlife Refuge System will be celebrating its 100th anniversary. This system is the world’s most unique network of lands and waters set aside specifically for the conservation of fish, wildlife and plants. President Theodore Roosevelt established the first refuge, 3- acre Pelican Island Bird Reservation in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, in 1903. Roosevelt went on to create 55 more refuges before he left office in 1909; today the refuge system encompasses more than 535 units spread over 94 million acres. Leading up to 2003, the Tideline will feature each national wildlife refuge in the San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Complex. This complex is made up of seven Refuges (soon to be eight) located throughout the San Francisco Bay Area and headquartered at Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge in Fremont. We hope these articles will enhance your appreciation of the uniqueness of each refuge and the diversity of habitats and wildlife in the San Francisco Bay Area. San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge Tucked away in the northern reaches of the San Francisco Bay estuary lies a body of water and land unique to the San Francisco Bay Area. Every winter, thousands of canvasbacks - one of North America’s largest and fastest flying ducks, will descend into San Pablo Bay and the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. This refuge not only boasts the largest wintering population of canvasbacks on the west coast, it protects the largest remaining contiguous patch of pickleweed-dominated tidal marsh found in the northern San Francisco Bay - habitat critical to Aerial view of San Pablo Bay NWR the survival of the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse. -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

CALENDAR ITEM Howe AUTHORIZE the PURCHASE with KAPILOFF

CALENDAR ITEM A 9 61 03127190 '~ 3 W 24425 AD 117 Howe AUTHORIZE THE PURCHASE WITH KAPILOFF LANO BANK TRUST FUNDS A PARCEL OF LANO KNOWN AS THE MARIN ISLANDS IN SAN RAFAEL BAY, CITY OF SAN RAFAEL. MARIN COUNTY APPLICANT: State Lands Commission as trustee 9f the Kapiloff Land Bank Fund Staff of the California Coastal Conservancy, Marin Open ~pace District, Fish and Wildlife Service and the Stjte Lands Commission have been considering the purchase of tid~lands apd two islands known as the Marin Islands, located in San Rafael Bay, City of San Rafael, Marin County. These agencies will contribute one-half of the purchase price. It is proposed that the Commission contribute $500,000 toward this -~mount from the Kapiloff Land Bank Fund. Private funding_ will be raised to cover the remaining half of the purchase price. The subject parcel is approximately 339 acres: 32'6 acres are tideland lots located in the bed of San Rafael Bay. The tideland portion of the subjact property is presently unfilled and in a natural condition, and as such, ·remain an integral part of the overall San Francisco Bay estuarine ecosystem., The West Marin Island is 2.90 acres of open space used primarily for nesting purposes by a variety of waterfowl. This island is, uegetated with native grasses and small trees. Due to its isolated location and terrain, the island is a productive rookery For a variety oF water fowl visiting the Bay area. The island has been identified by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service as having the largest heron rookery in San Franci~co Bay. -

National Wildlife Refuge System

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System o 60 o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 65 o o 145 145 o 150 155 o 160 165 170 175 E 180 70 175 W 170 165 160 155 150 140 135 130 70 125 120 115 Barrow A E A R C T I S C C O C E A N H R T 30 o U F O Midway Atoll NWR E A U K B e C m iti ar Teshekpuk PACIFIC ISLANDS H H Lake Prudhoe Bay a M w a ai I k ian s 0 200 400 MILES Is a land l 1 s NW S A R E Marianas Trench MNM (Island Unit) 0 300 600 KILOMETERS ) t A i n U R TROPIC OF CANCER o c SCALE 1:29,000,000 i Papahanaumokuakea MNM R n o o 65 a U c Albers equal area projection, standard parallels 7 S and 20 N, Colville l o o Alaska Maritime V S ( central meridian 174 30' E Honolulu Arctic M H S N A 55 W M A o o I 20 h I I c Noatak n A e r T See inset map of s a Hawaii below R n a i A r RC a TIC C M IR C / LE R K R Guam NWR o t Kobuk e W z NORTHERN MARIANA e A in N b p Wake Atoll NWR and l u e u a c r ISLANDS r i e s o k P F Pacific Remote Islands MNM (UNITED STATES) a f t S R o i o M u c a r r n a Selawik A d r Yukon Flats t i Yukon a S ti n m a N i r Johnston Atoll NWR and Alaska Maritime e a Kanuti M A Pacific Remote Islands MNM Mariana Trench NWR / Marianas Trench MNM (Trench Unit) n g E r i R C B e 10 o N M R A O oyukuk R S K H A Koyukuk L L C I S L I Fairbanks A Nome N F Kingman Reef NWR and FED D I ERA S A Nowitna TED Pacific Remote Islands MNM l Tanana STA C Palmyra Atoll NWR and a TES sk A OF a MI A Pacific Remote Islands MNM Innoko D CRO M NE P St. -

Tide Rising Spring 2021 Volume II, Issue 3

Tide Rising Spring 2021 Volume II, Issue 3 Publisher & Editor: San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society (SFBWS). SFBWS is a not-for-profit Friends Group for the San Francisco Bay NWR Complex, working along with many Refuge volunteers to keep our public lands sustainable for you and wildlife. TABLE OF CONTENTS Endangered & Threatened Species In this issue: Refuge Spotlight: • Learn what our Friends group can do to advocate for the endangered • ENDANGERED SPECIES: Business as Usual in a Pandemic? and threatened species on our Refuge Complex. Find ideas and read an • ENDANGERED SPECIES: Clade X? interview with CORFA President: Coalition of Refuge Friends & Advocates. • See how the Veterans Affairs (VA) Alameda Point staff and volunteers Corners pivoted during the pandemic supporting the least tern, an endangered • SFBWS President Column species on our Refuge. Not quite business as usual. • Volunteers • Discover whether a new species has been found on the Antioch Dunes • Don Edwards Volunteers NWR? Learn more about the evening primrose, Clade X. • North Bay Refuge Volunteers • Volunteers in FY2020: they are the lifeblood of the Refuge Complex. Last • Photography Corner year and a pandemic didn’t stop our USFWS volunteers. • Take a look at the photographs galore this issue! People of Note • Interview with Joan Patterson, Enjoy the San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society SPRING Newsletter! long time Refuge advocate San Francisco Bay Wildlife Society SFBWS Info Editors: Ceal Craig, PhD; Renee Fitzsimons. • Donor Recognition Contributors: Ceal Craig, Mary Deschene, Renee Fitzsimons (SFBWS). • Membership Information Louis Terrezas (USFWS), Meg Marriott (USFWS), Paul Mueller (USFWS), Susan Euing (USFWS), Earth Day 2021 Info Photographers: Ambarish Goswami, Ceal Craig, Cindy Roessler, Joanne Ong, Louis Terrazas, Say Zhee Lim, S. -

By April Thygeson

Color Page “The Voice of the Waterfront” April 2012 Vol.13, No.4 Opening Day on the Bay American Spirit at Annual Bash 40,000 Miles of Water World Racers to Stop in Oakland A Very Clean Marina Initiative Takes on Raw Sewage Complete Ferry Schedules for all SF Lines Color Page TASTING ROOM OPEN DAILY FROM 11AM TO 6PM TASTE, TOUR RELAX Just a short ferry ride across San Francisco Bay lies the original urban winery, Rosenblum Cellars. Alameda is our urban island with no pretension. Our tasting room is a true gem, with a rustic urban charm that attracts fans from around the world to enjoy the unique, relaxed atmosphere. TWO FOR ONE TASTING with this ad. $10 value www.rosenblumcellars.com 2900 Main St. Suite 1100 Alameda, CA 1-877-GR8-ZINS Please enjoy our wines responsibly. © 2011 Rosenblum Cel Alameda, CA www.DrinkiQ.com 2 April 2012 www.baycrossings.com columns features 05 WHO’S AT THE HELM? 12 OPENING DAY Captain Chuck Elles Catch the Spirit at 95th by Matt Larson Annual Celebration by April Thygeson 11 08 BAYKEEPER Clean Boat Repair Tips 14 GREEN PAGES guides by Deb Self Clean Marina Initiative Puts Brakes on Sewage WATERFRONT ACTIVITIES 22 Our recreational resource guide 09 SAILING ADVENTURES by Bill Picture The Marin Islands 24 WETA FERRY SCHEDULES by Captain Ray news Be on time for last call AROUND THE BAY 20 CULTURAL CURRENTS 04 511 Transit Info App 26 To see, be, do, know Destination: L.A. Debuts for Smartphones by Paul Duclos by Craig Noble ON OUR COVER 06 WATERFRONT NEWS Foreign Trade Drives April 2012 Volume 13, Number 4 Growth at Bay Ports Bobby Winston, Proprietor by Patrick Burnson Joyce Aldana, President Joel Williams, Publisher Patrick Runkle, Editor Around-the-World Racers ADVERTISING & MARKETING 10 Joel Williams, Advertising & Marketing Director to Make Stop in Oakland GRAPHICS & PRODUCTION Francisco Arreola, Designer / Web Producer AMERICA’S CUP ART DIRECTION 16 Francisco Arreola; Patrick Runkle; Joel Williams Final Agreement with S.F. -

The List of National System Mpas List Is Current As of July 2013

The List of National System MPAs List is current as of July 2013 FEDERAL MARINE PROTECTED AREAS Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge (Texas) Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge (Florida) Breton National Wildlife Refuge (Louisiana) Tybee National Wildlife Refuge (Georgia, South Carolina) Marine National Monument Cape May National Wildlife Refuge (New Jersey) Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge (South Carolina) Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument (Hawaii) Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge (South Carolina) Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuge (Virginia) Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge (North Carolina) Wassaw National Wildlife Refuge (Georgia) National Marine Fisheries Service Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuge (Florida) Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge (New York) Lydonia Canyon Gear Restricted Area Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge (Florida) Willapa National Wildlife Refuge (Washington) Norfolk Canyon Gear Restricted Area Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge (Maryland, Virginia) Wolf Island National Wildlife Refuge (Georgia) Oceanographer Canyon Gear Restricted Area Conscience Point National Wildlife Refuge (New York) Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge (Alaska) Veatch Canyon Gear Restricted Area Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge (Florida) Cross Island National Wildlife Refuge (Maine) FEDERAL / STATE PARTNERSHIP MARINE PROTECTED AREAS National Marine Sanctuaries Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge (Florida) Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (California) Currituck National Wildlife Refuge -

Science and Cross-Habitat Goals for All Subtidal Habitat Types

CHAPTER THREE Science and Cross-Habitat Goals for All Subtidal Habitat Types his chapter discusses informational needs and issues that cross multiple habitat types, including the water column as a unifying habitat Ttype. It includes a conceptual description of all subtidal habitats and the water column. It lays out foundational science and research goals for all subtidal habitat types, and discusses issues that warrant management and restoration goals for all habitats—for example, invasive species, oil spills, marine debris, and public access and awareness. Conceptual Model for All Habitats The habitat types discussed in this report (Figure 3-1) include habitats defined by physical structure (soft-bottom, rock, artificial substrate), habitats created partly by organisms (eelgrass beds, shellfish beds, and macroalgal beds), and the water column (see next section). All of the habitats except the water column are fixed in place, so the water column must be considered as part of these habitats as well as a separate habitat itself. The various subtidal habitats support valued ecosystem services (see Chapter 1), although the degree of support, and the relationship of quantity of habitat to level of support, are unknown. Conceptual models, including text and diagrams, were developed to describe the broader subtidal system, and for each of the habitat types. The habitat-specific models in subsequent chapters provide informa- tion on what each habitat does, both in terms of its function and the ecosystem services it supports. They also describe short- and long- term threats—human and other activities that may impair or reduce the amount of each habitat. The Water Column In setting goals for subtidal habitat, the Subtidal Goals Project used the water column—the water covering submerged substrate, includ- Shallow subtidal habitat at the Marin Islands National ing all volume between the substrate and the water surface—as an Wildlife Refuge. -

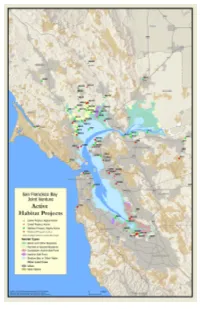

Activeprojects 06 Tabloid Map.Pdf

Coastal (C) Suisun Marsh (S) C163 Redwood Creek/Big Lagoon S17 Bay Point Regional Shoreline Restoration Project C192 San Pedro Creek Tidal Area S54 Dutch Slough C433 Lagunitas Creek Watershed - Land Acquisition to Protect Creeks and Coho in West Marin S91 Lower Marsh Creek - Oakley C421 Giacomini Wetlands S94 Lower Walnut Creek Restoration - Mouth of creek to Hwy 242 Central Bay (CB) S99 Marsh Creek - Griffith Park CB30 Canalways (San Rafael) S102 Martinez Regional Shoreline Marsh Restoration CB34 Cerrito Creek - Pacific East Mall S104 McNabney (Shell) Marsh CB34 Cerrito Creek - El Cerrito Plaza S133 Pacheco Marsh CB46 Crissy Field S238 Suisun Creek Watershed Enhancement Program CB63 Glen Echo Creek bank stabilization between Monte Vista Avenue and Montell Street S511 Marsh Creek Reservoir Rehabilitation CB84 Lake Merritt (Oakland) South Bay (SB) CB84 Lake Merritt Channel SB3 Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration CB137 Peralta Creek SB6 Alhambra Valley Creek Coalition Restoration Project CB199 Sausal Creek - Dimond Canyon SB15 Pete's Landing at Middle Bair Island CB205 Schoolhouse Creek mouth, Eastshore State Park SB15 Bair Island CB247 Tennessee Hollow SB69 Guadalupe River Restoration CB267 Richmond Bayshore Stewardship SB109 Moffett Field Wetlands CB274 Candlestick Point -- Yosemite Slough Wetland Restoration SB125 New Chicago Marsh CB281 Codornices Creek, Kains to San Pablo SB136 Patterson Ranch, Coyote Hills Regional Park CB281 Codornices Creek, middle (San Pablo - MLK) SB231 South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Projects CB282 Community-Based -

Locations of Sites Nominated to the National System of Mpas

Locations of Sites Nominated to The National System of MPAs Alabama Number of Sites: 2 1 Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge 2 Grand Bay National Wildlife Refuge Alaska Number of Sites: 4 1 Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge 2 Arctic National Wildlife Refuge 3 Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve 4 Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge American Samoa Number of Sites: 2 1 Aua 2 Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary California Number of Sites: 73 1 Ano Nuevo ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 2 Ano Nuevo State Marine Conservation Area 3 Asilomar State Marine Reserve 4 Big Creek State Marine Conservation Area 5 Big Creek State Marine Reserve 6 Bird Rock ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 7 Bodega ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 8 Cambria State Marine Conservation Area 9 Carmel Bay ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 10 Carmel Bay State Marine Conservation Area 11 Carmel Pinnacles State Marine Reserve 12 Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary 13 Channel Islands National Park 14 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary 15 Del Mar Landing ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 16 Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge 17 Double Point ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 18 Duxbury Reef ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 19 Edward F. Ricketts State Marine Conservation Area 20 Elkhorn Slough State Marine Conservation Area Page 1 of 8 Friday, April 03, 2009 21 Elkhorn Slough State Marine Reserve 22 Farallon Islands ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 23 Farnsworth Bank ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 24 Gerstle Cove ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 25 Greyhound Rock State Marine Conservation Area 26 Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary 27 Heisler Park ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 28 Irvine Coast ASBS State Water Quality Protection Area 29 James V.