Pomona Oaks Exposure Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies of Physico of Liquid

MD Simulation of Liquid Pentane Isomers Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1999, Vol. 20, No. 8 897 Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies of Physico Chemical Properties of Liquid Pentane Isomers Seng Kue Lee and Song Hi Lee* Department of Chemistry, Kyungsung University, Pusan 608-736, Korea Received January 15, 1999 We have presented the thermodynamic, structural and dynamic properties of liquid pentane isomers - normal pentane, isopentane, and neopentane - using an expanded collapsed atomic model. The thermodynamic prop erties show that the intermolecular interactions become weaker as the molecular shape becomes more nearly spherical and the surface area decreases with branching. The structural properties are well predicted from the site-site radial, the average end-to-end distance, and the root-mean-squared radius of gyration distribution func tions. The dynamic properties are obtained from the time correlation functions - the mean square displacement (MSD), the velocity auto-correlation (VAC), the cosine (CAC), the stress (SAC), the pressure (PAC), and the heat flux auto-correlation (HFAC) functions - of liquid pentane isomers. Two self-diffusion coefficients of liq uid pentane isomers calculated from the MSD's via the Einstein equation and the VAC's via the Green-Kubo relation show the same trend but do not coincide with the branching effect on self-diffusion. The rotational re laxation time of liquid pentane isomers obtained from the CAC's decreases monotonously as branching increas es. Two kinds of viscosities of liquid pentane isomers calculated from the SAC and PAC functions via the Green-Kubo relation have the same trend compared with the experimental results. The thermal conductivity calculated from the HFAC increases as branching increases. -

Measurements of Higher Alkanes Using NO Chemical Ionization in PTR-Tof-MS

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 14123–14138, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-14123-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Measurements of higher alkanes using NOC chemical ionization in PTR-ToF-MS: important contributions of higher alkanes to secondary organic aerosols in China Chaomin Wang1,2, Bin Yuan1,2, Caihong Wu1,2, Sihang Wang1,2, Jipeng Qi1,2, Baolin Wang3, Zelong Wang1,2, Weiwei Hu4, Wei Chen4, Chenshuo Ye5, Wenjie Wang5, Yele Sun6, Chen Wang3, Shan Huang1,2, Wei Song4, Xinming Wang4, Suxia Yang1,2, Shenyang Zhang1,2, Wanyun Xu7, Nan Ma1,2, Zhanyi Zhang1,2, Bin Jiang1,2, Hang Su8, Yafang Cheng8, Xuemei Wang1,2, and Min Shao1,2 1Institute for Environmental and Climate Research, Jinan University, 511443 Guangzhou, China 2Guangdong-Hongkong-Macau Joint Laboratory of Collaborative Innovation for Environmental Quality, 511443 Guangzhou, China 3School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences), 250353 Jinan, China 4State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environmental Protection and Resources Utilization, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 510640 Guangzhou, China 5State Joint Key Laboratory of Environmental Simulation and Pollution Control, College of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, Peking University, 100871 Beijing, China 6State Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Boundary Physics and Atmospheric Chemistry, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese -

Supporting Information for Modeling the Formation and Composition Of

Supporting Information for Modeling the Formation and Composition of Secondary Organic Aerosol from Diesel Exhaust Using Parameterized and Semi-explicit Chemistry and Thermodynamic Models Sailaja Eluri1, Christopher D. Cappa2, Beth Friedman3, Delphine K. Farmer3, and Shantanu H. Jathar1 1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 80523 2 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California Davis, Davis, CA, USA, 95616 3 Department of Chemistry, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 80523 Correspondence to: Shantanu H. Jathar ([email protected]) Table S1: Mass speciation and kOH for VOC emissions profile #3161 3 -1 - Species Name kOH (cm molecules s Mass Percent (%) 1) (1-methylpropyl) benzene 8.50×10'() 0.023 (2-methylpropyl) benzene 8.71×10'() 0.060 1,2,3-trimethylbenzene 3.27×10'(( 0.056 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene 3.25×10'(( 0.246 1,2-diethylbenzene 8.11×10'() 0.042 1,2-propadiene 9.82×10'() 0.218 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene 5.67×10'(( 0.088 1,3-butadiene 6.66×10'(( 0.088 1-butene 3.14×10'(( 0.311 1-methyl-2-ethylbenzene 7.44×10'() 0.065 1-methyl-3-ethylbenzene 1.39×10'(( 0.116 1-pentene 3.14×10'(( 0.148 2,2,4-trimethylpentane 3.34×10'() 0.139 2,2-dimethylbutane 2.23×10'() 0.028 2,3,4-trimethylpentane 6.60×10'() 0.009 2,3-dimethyl-1-butene 5.38×10'(( 0.014 2,3-dimethylhexane 8.55×10'() 0.005 2,3-dimethylpentane 7.14×10'() 0.032 2,4-dimethylhexane 8.55×10'() 0.019 2,4-dimethylpentane 4.77×10'() 0.009 2-methylheptane 8.28×10'() 0.028 2-methylhexane 6.86×10'() -

Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications This Journal Is © the Royal Society of Chemistry 2012

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Supplementary Material Guest-controlled Self-Sorting in Assemblies driven by the Hydrophobic Effect Haiying Gan, Bruce C. Gibb* Department of Chemistry University of New Orleans LA 70148 Email: [email protected] S1 Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Table of Contents General p S3 1H-NMR spectra of 1 and 2, and mixture of hosts, in the absence of guests p S4 1H-NMR spectra of the complexes of 1.2 and hydrocarbons n-pentane through n-heptadecane p S5-S8 Example COSY and NOESY NMR data (for n-undecane hetero-complex) p S9 Pulse-gradient stimulated spin-echo NMR studies p S11 Table of Percentage of Hetero-complex Formation p S12 References p S13 S2 Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Experimental section General All reagents were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company and used as received without further purification. Host 1 and 2 were synthesized as previously reported.1,2 NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported relative to D2O (4.80 ppm). Endo Me c O O O O O O O O O O g O O g O O O d O d HO O HO O HO f O OH OH HO f O OH OH O b O O b O H H H H H H H H O e O e O O O O O O O O O O O O O O j j H H a H H H Ha H H m l m l HO O HO O O OH O OH HO O HO O O OH O OH 1 2 S3 Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 1H-NMR spectra of host 1, 2 and mixture of hosts in the absence of guests Figure S1: 1H NMR spectra of: 1) 1 mM of 1; 2) 1 mM of 2; 3) 0.5 mM of both 1 and 2 (all 10 mM sodium tetraborate solution). -

Vapor Pressures and Vaporization Enthalpies of the N-Alkanes from 2 C21 to C30 at T ) 298.15 K by Correlation Gas Chromatography

BATCH: je1a04 USER: jeh69 DIV: @xyv04/data1/CLS_pj/GRP_je/JOB_i01/DIV_je0301747 DATE: October 17, 2003 1 Vapor Pressures and Vaporization Enthalpies of the n-Alkanes from 2 C21 to C30 at T ) 298.15 K by Correlation Gas Chromatography 3 James S. Chickos* and William Hanshaw 4 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of MissourisSt. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63121 5 6 The temperature dependence of gas chromatographic retention times for n-heptadecane to n-triacontane 7 is reported. These data are used to evaluate the vaporization enthalpies of these compounds at T ) 298.15 8 K, and a protocol is described that provides vapor pressures of these n-alkanes from T ) 298.15 to 575 9 K. The vapor pressure and vaporization enthalpy results obtained are compared with existing literature 10 data where possible and found to be internally consistent. Sublimation enthalpies for n-C17 to n-C30 are 11 calculated by combining vaporization enthalpies with fusion enthalpies and are compared when possible 12 to direct measurements. 13 14 Introduction 15 The n-alkanes serve as excellent standards for the 16 measurement of vaporization enthalpies of hydrocarbons.1,2 17 Recently, the vaporization enthalpies of the n-alkanes 18 reported in the literature were examined and experimental 19 values were selected on the basis of how well their 20 vaporization enthalpies correlated with their enthalpies of 21 transfer from solution to the gas phase as measured by gas 22 chromatography.3 A plot of the vaporization enthalpies of 23 the n-alkanes as a function of the number of carbon atoms 24 is given in Figure 1. -

Table 2. Chemical Names and Alternatives, Abbreviations, and Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Numbers

Table 2. Chemical names and alternatives, abbreviations, and Chemical Abstracts Service registry numbers. [Final list compiled according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Web site (http://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/); NIST Standard Reference Database No. 69, June 2005 release, last accessed May 9, 2008. CAS, Chemical Abstracts Service. This report contains CAS Registry Numbers®, which is a Registered Trademark of the American Chemical Society. CAS recommends the verification of the CASRNs through CAS Client ServicesSM] Aliphatic hydrocarbons CAS registry number Some alternative names n-decane 124-18-5 n-undecane 1120-21-4 n-dodecane 112-40-3 n-tridecane 629-50-5 n-tetradecane 629-59-4 n-pentadecane 629-62-9 n-hexadecane 544-76-3 n-heptadecane 629-78-7 pristane 1921-70-6 n-octadecane 593-45-3 phytane 638-36-8 n-nonadecane 629-92-5 n-eicosane 112-95-8 n-Icosane n-heneicosane 629-94-7 n-Henicosane n-docosane 629-97-0 n-tricosane 638-67-5 n-tetracosane 643-31-1 n-pentacosane 629-99-2 n-hexacosane 630-01-3 n-heptacosane 593-49-7 n-octacosane 630-02-4 n-nonacosane 630-03-5 n-triacontane 638-68-6 n-hentriacontane 630-04-6 n-dotriacontane 544-85-4 n-tritriacontane 630-05-7 n-tetratriacontane 14167-59-0 Table 2. Chemical names and alternatives, abbreviations, and Chemical Abstracts Service registry numbers.—Continued [Final list compiled according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Web site (http://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/); NIST Standard Reference Database No. -

LE Hatch, W. Luo, JF Pankow, RJ Yokelson 2, CE Stockwell 2, and KC Barsanti

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., 14, 23237–23307, 2014 www.atmos-chem-phys-discuss.net/14/23237/2014/ doi:10.5194/acpd-14-23237-2014 ACPD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 14, 23237–23307, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Atmospheric Chemistry Identification of and Physics (ACP). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in ACP if available. NMOCs in biomass burning smoke Identification and quantification of L. E. Hatch et al. gaseous organic compounds emitted from biomass burning using Title Page Abstract Introduction two-dimensional gas Conclusions References chromatography/time-of-flight mass Tables Figures spectrometry J I L. E. Hatch1, W. Luo1, J. F. Pankow1, R. J. Yokelson2, C. E. Stockwell2, and J I 1 K. C. Barsanti Back Close 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Portland State University, Portland, Full Screen / Esc Oregon 2 Department of Chemistry, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana Printer-friendly Version Received: 15 August 2014 – Accepted: 19 August 2014 – Published: 10 September 2014 Interactive Discussion Correspondence to: K. C. Barsanti ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 23237 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract ACPD The current understanding of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation within biomass burning (BB) plumes is limited by the incomplete identification and quan- 14, 23237–23307, 2014 tification of the non-methane organic compounds (NMOCs) emitted from such fires. 5 Gaseous organic compounds were collected on sorbent cartridges during labora- Identification of tory burns as part of the fourth Fire Lab at Missoula Experiment (FLAME-4), with NMOCs in biomass analysis by two-dimensional gas chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry burning smoke (GC × GC/TOFMS). -

N-Alkane Category: Decane, Undecane, Dodecane (CAS Nos

June 17, 2004 n-Alkane Category: decane, undecane, dodecane (CAS Nos. 124-18-5, 1120-21-4, 112-40-3) Voluntary Children’s Chemical Evaluation Program (VCCEP) Tier 1 Pilot Submission Docket Number OPPTS – 00274D American Chemistry Council n-Alkane VCCEP Consortium Sponsors: Chevron Phillips Chemical Company LP Sasol North America Inc. Shell Chemical LP June 17, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary of Terms 4 1. Executive Summary 5 2. Basis for Inclusion in the VCCEP Program 2.1 Total Exposure Assessment Methodology Data 10 2.2 Air Monitoring Data 11 2.3 How Sponsors Were Identified for the n-Alkane VCCEP Effort 12 3. Previous and On-Going Health Assessments 3.1 OECD SIDS/ICCA HPV Imitative 14 3.2 Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Criteria Working Group 15 3.3 Hydrocarbon Solvent Guidance Group Values (GGVs) for Setting Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) for Hydrocarbon Solvents 15 4. Regulatory Overview 4.1 CPSC Child-Resistant Packaging for Hydrocarbons 16 4.2 Occupational Exposure Limits 16 4.3 VOC Regulations 17 5. Product Overview 5.1 Physical, Chemical, and Environmental Fate Properties 18 5.2 Production of n-Alkanes 20 5.3 Uses for n-Alkane Products 20 5.4 Petroleum Products Which Contain n-Alkanes 21 6. Exposure Assessment 6.1 Summary 25 6.2 Non-Occupational Exposure 28 6.2.1 Indoor Sources of Exposure 6.2.2 Outdoor Source of Exposure 6.2.3 Unique Children’s Exposure 6.3 Integrated 24 hour Exposure 36 6.4 Occupational Exposure 36 6.5 Potential for Dermal and Oral Exposure 40 6.6 Selection of Exposure Scenarios and Exposure Concentrations 43 7. -

Catalysis Science & Technology

Catalysis Science & Technology Accepted Manuscript This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication. Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. We will replace this Accepted Manuscript with the edited and formatted Advance Article as soon as it is available. You can find more information about Accepted Manuscripts in the Information for Authors. Please note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the text and/or graphics, which may alter content. The journal’s standard Terms & Conditions and the Ethical guidelines still apply. In no event shall the Royal Society of Chemistry be held responsible for any errors or omissions in this Accepted Manuscript or any consequences arising from the use of any information it contains. www.rsc.org/catalysis Page 1 of 12 Catalysis Science & Technology 1 Cu, Al and Ga based metal organic framework catalysts for the decarboxylation of oleic acid L. Yang, G. L. Ruess, M.A. Carreon * Keywords: metal organic frameworks,decarboxylation, fuel hydrocarbons Manuscript Abstract Herein we demonstrate the catalytic decarboxylation and conversion of oleic acid to paraffins, and hydrocarbons over bare and Pt supported Cu, Al and Ga based metal organic frameworks. Moderate degree of decarboxylation were observed for all metal organic framework catalysts. The incorporation of Pt with the porous frameworks resulted in high degrees of decarboxylation. All MOF catalysts showed high thermal stability, resulting in recyclable catalysts displaying low catalytic activity loss. -

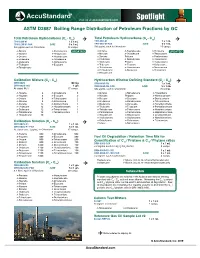

ASTM D2887 Boiling Range Distribution of Petroleum Fractions by GC

Visit us at accustandard.com ASTM D2887 Boiling Range Distribution of Petroleum Fractions by GC Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (C8 - C20) Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (C8 - C30) TPH-LOW-01 $ 50 / 1 x 1 mL TPH-MID-01 $ 65 / 1 x 1 mL TPH-LOW-01-PAK SAVE 20% $ 200 / 5 x 1 mL TPH-MID-01-PAK SAVE 20% $ 260 / 5 x 1 mL 500 µg/mL each in Chloroform 13 comps. 500 µg/mL each in Chloroform 25 comps. n-Octane n-Pentadecane UPDATED n-Octane n-Heptadecane n-Tricosane UPDATED n-Nonane n-Hexadecane n-Nonane n-Octadecane n-Tetracosane n-Decane n-Heptadecane n-Decane Pristane n-Pentacosane n-Undecane n-Octadecane n-Undecane n-Nonadecane n-Hexacosane n-Dodecane n-Nonadecane n-Dodecane Phytane n-Heptacosane n-Tridecane n-Eicosane n-Tridecane n-Eicosane n-Octacosane n-Tetradecane n-Tetradecane n-Heneicosane n-Nonacosane n-Pentadecane n-Docosane n-Triacontane n-Hexadecane Calibration Mixture (C6 - C44) Hydrocarbon Window Defining Standard (C8 - C40) DRH-002N $ 30 / 100 mg DRH-008S-R2 $ 65 / 1 x 1 mL DRH-002N-10X $ 40 / 1 gm DRH-008S-R2-PAK SAVE 20% $ 260 / 5 x 1 mL At stated Wt.% 17 comps. 500 µg/mL each in Chloroform 35 comps. n-Hexane 6 n-Octadecane 5 n-Octane n-Nonadecane n-Triacontane n-Heptane 6 n-Eicosane 2 n-Nonane Phytane n-Hentriacontane n-Octane 8 n-Tetracosane 2 n-Decane n-Eicosane n-Dotriacontane n-Nonane 8 n-Octacosane 1 n-Undecane n-Heneicosane n-Tritriacontane n-Decane 12 n-Dotriacontane 1 n-Dodecane n-Docosane n-Tetratriacontane n-Undecane 12 n-Hexatriacontane 1 n-Tridecane n-Tricosane n-Pentatriacontane n-Dodecane 12 n-Tetracontane 1 n-Tetradecane n-Tetracosane n-Hexatriacontane n-Tetradecane 12 n-Tetratetracontane 1 n-Pentadecane n-Pentacosane n-Heptatriacontane n-Hexadecane 10 n-Hexadecane n-Hexacosane n-Octatriacontane n-Heptadecane n-Heptacosane n-Nonatriacontane n-Octadecane n-Octacosane n-Tetracontane Calibration Solution (C6 - C44) DRH-002S-R1 $ 50 / 1 x 1 mL Pristane n-Nonacosane DRH-002S-R1-PAK SAVE 20% $ 200 / 5 x 1 mL At stated conc. -

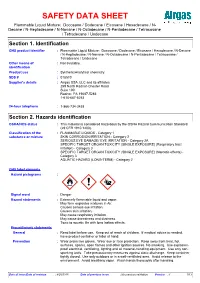

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET Flammable Liquid Mixture: Docosane / Dodecane / Eicosane / Hexadecane / N- Decane / N-Heptadecane / N-Nonane / N-Octadecane / N-Pentadecane / Tetracosane / Tetradecane / Undecane Section 1. Identification GHS product identifier : Flammable Liquid Mixture: Docosane / Dodecane / Eicosane / Hexadecane / N-Decane / N-Heptadecane / N-Nonane / N-Octadecane / N-Pentadecane / Tetracosane / Tetradecane / Undecane Other means of : Not available. identification Product use : Synthetic/Analytical chemistry. SDS # : 018510 Supplier's details : Airgas USA, LLC and its affiliates 259 North Radnor-Chester Road Suite 100 Radnor, PA 19087-5283 1-610-687-5253 24-hour telephone : 1-866-734-3438 Section 2. Hazards identification OSHA/HCS status : This material is considered hazardous by the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200). Classification of the : FLAMMABLE LIQUIDS - Category 1 substance or mixture SKIN CORROSION/IRRITATION - Category 2 SERIOUS EYE DAMAGE/ EYE IRRITATION - Category 2A SPECIFIC TARGET ORGAN TOXICITY (SINGLE EXPOSURE) (Respiratory tract irritation) - Category 3 SPECIFIC TARGET ORGAN TOXICITY (SINGLE EXPOSURE) (Narcotic effects) - Category 3 AQUATIC HAZARD (LONG-TERM) - Category 2 GHS label elements Hazard pictograms : Signal word : Danger Hazard statements : Extremely flammable liquid and vapor. May form explosive mixtures in Air. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. May cause drowsiness and dizziness. Toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. Precautionary statements General : Read label before use. Keep out of reach of children. If medical advice is needed, have product container or label at hand. Prevention : Wear protective gloves. Wear eye or face protection. Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames and other ignition sources. No smoking. Use explosion- proof electrical, ventilating, lighting and all material-handling equipment. -

Evaluation of the Valuable Oxygenated Components in Iranian Rose Water

International Journal of ChemTech Research CODEN (USA): IJCRGG ISSN : 0974-4290 Vol.6, No.11, pp 4782-4788, Oct-Nov 2014 Evaluation of the Valuable Oxygenated Components in Iranian Rose Water Marjan Mahboubifar 1,2, Sara Shahabipour1, Katayoun Javidnia*1 1 Medicinal and Natural Products Chemistry Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran, P. O. Box: 71345-3388. 2Student Research Committee, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran *Corres.author: [email protected], [email protected], Phone No.: +98 711 2303872; Fax: +98 711 2332225 Abstract: Rose water is one of the most important products obtained from Rosa genus (Rosaceae). Although Iran is one of the main producers of rose water, limited research has been done on it. A simple distillation and a Clevenger-type apparatus were used to obtain rose water and rose oil. All the volatile concentrates were investigated for their chemical composition by gas chromatography (GC) and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Volatile concentrates from three commercial samples of rose water, purchased from the local market, were also studied. The major component of laboratory prepared and commercial rose water samples was found to be phenylethyl alcohol (45.1%-85.4%), while aliphatic hydrocarbons were identified as the main constituents of the oily phase of rose water extracted by simple hydrodistillation and Clevenger-type distillation method (49.1%, 60.3%). Our results showed that the volatile obtained from the oily phase had lower economic value than rose water. Keywords: Rose water, Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, hydrodistillation, Phenylethyl alcohol. Introduction and Experimental The Rosa genus belongs to the Rosaceae family and is represented by about 200 species and also more than 18000 cultivars(1).