RAIL SYSTEM PLAN December 2018 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-CSX-Annual-Report.Pdf

CSX Corporation 2019 Annual Report 2019 Annual Report In this Report 2 Message from the CEO 4 Delivering Results 5 Safety Focused 6 Raising the Bar on Rail Service 7 Positioned for Growth 8 Environmental, Social and Governance BC Our Board of Directors and Executive Management Major Terminal CSX Rail Service CSX Operating Agreements 3 Powered to Perform CSX brings on-time delivery, first-class service, and a seamless shipping experience to customers across an extensive network that reaches nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population and a diverse set of consumers and industrial end markets. A leading supplier of rail-based freight transportation, CSX is powered to deliver comprehensive service solutions. CSX Revenue Mix 21% Chemicals 66% Merchandise 12% Agricultural and Food 11% Automotive 8% Forest Products 6% Metals and Equipment 5% Minerals 4% Fertilizers 18% Coal 15% Intermodal Message from the CEO Transforming Service into Growth Dear Fellow Shareholders, CSX’s 2019 results have set a new standard of financial and Optimizing the customer experience was also a critical operating performance for U.S. railroads. CSX employees 2019 focus area, as employees across all departments ran the network better than at any point in the company’s designed, delivered and supported exceptional rail service. history, setting new efficiency records throughout the year. We measure service success for merchandise and The CSX team delivered unparalleled service and reliability intermodal shipments by our performance on meeting trip for customers, laying the foundation for long-term business plan schedules, calculated to the hour and minute, for every growth in the months and years ahead, all while driving carload, container and trailer on the railroad, including industry-leading safety performance. -

Amtrak's Rights and Relationships with Host Railroads

Amtrak’s Rights and Relationships with Host Railroads September 21, 2017 Jim Blair –Director Host Railroads Today’s Amtrak System 2| Amtrak Amtrak’s Services • Northeast Corridor (NEC) • 457 miles • Washington‐New York‐Boston Northeast Corridor • 11.9 million riders in FY16 • Long Distance (LD) services • 15 routes • Up to 2,438 miles in length Long • 4.65 million riders in FY16 Distance • State‐supported trains • 29 routes • 19 partner states • Up to 750 miles in length State- • 14.7 million riders in FY16 supported3| Amtrak Amtrak’s Host Railroads Amtrak Route System Track Ownership Excluding Terminal Railroads VANCOUVER SEATTLE Spokane ! MONTREAL PORTLAND ST. PAUL / MINNEAPOLIS Operated ! St. Albans by VIA Rail NECR MDOT TORONTO VTR Rutland ! Port Huron Niagara Falls ! Brunswick Grand Rapids ! ! ! Pan Am MILWAUKEE ! Pontiac Hoffmans Metra Albany ! BOSTON ! CHICAGO ! Springfield Conrail Metro- ! CLEVELAND MBTA SALT LAKE CITY North PITTSBURGH ! ! NEW YORK ! INDIANAPOLIS Harrisburg ! KANSAS CITY ! PHILADELPHIA DENVER ! ! BALTIMORE SACRAMENTO Charlottesville WASHINGTON ST. LOUIS ! Richmond OAKLAND ! Petersburg ! Buckingham ! Newport News Norfolk NMRX Branch ! Oklahoma City ! Bakersfield ! MEMPHIS SCRRA ALBUQUERQUE ! ! LOS ANGELES ATLANTA SCRRA / BNSF / SDN DALLAS ! FT. WORTH SAN DIEGO HOUSTON ! JACKSONVILLE ! NEW ORLEANS SAN ANTONIO Railroads TAMPA! Amtrak (incl. Leased) Norfolk Southern FDOT ! MIAMI Union Pacific Canadian Pacific BNSF Canadian National CSXT Other Railroads 4| Amtrak Amtrak’s Host Railroads ! MONTREAL Amtrak NEC Route System -

Summer 2007 TOD Sketchbook

Central Florida Commuter Rail Summer 2007 Central Florida Commuter Rail On the Inside: page Introduction ........................................ 1 DeLand Station................................... 5 Fort Florida Station ............................ 7 Sanford Station................................... 9 Lake Mary Station ............................ 11 Longwood Station............................. 13 Altamonte Springs Station................ 15 Maitland Station............................... 17 Winter Park Station.......................... 19 Florida Hospital Station ................... 21 LYNX Central Station......................... 23 Church Street Station........................ 25 Orlando Amtrak Station ................... 27 Sand Lake Road Station................... 29 Meadow Woods Station .................... 31 Osceola Parkway Station .................. 33 Kissimmee Station............................ 35 Poinciana Station.............................. 37 The Central Florida Commuter Rail project will provide the opportunity not only to move people more efficiently, but to also build new, walkable, transit-oriented communities around some of its stations and strengthen existing communities around others. In February 2007, FDOT conducted a week long charrette process, individually meeting with the agencies and major stakeholders from DeLand each of the jurisdictions along the proposed 61-mile commuter rail corridor. These The plans and concepts included: Volusia County, Seminole County, illustrated in this report Orange County, -

2.0 Current Freight Rail System and Services in Florida

Investment Element of the 2010 Florida Rail System Plan 2.0 Current Freight Rail System and Services in Florida 2.1 Overview The Florida rail system is comprised of 2,786 miles of mainline track, which are owned by 15 operating line-haul railroads and terminal or switching companies, as well as 81 miles owned by the State of Florida. Florida’s rail system includes 2 Class I Railroads (CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Corporation), 1 Class II (Florida East Coast Railway), 11 Class III (Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway AN Railway, Bay Line Railroad, First Coast Railroad, Florida West Coast Railroad, Florida Central Railroad, Florida Midland Railroad, Florida Northern Railroad, Georgia and Florida Railway, Seminole Gulf Railway, and South Central Florida Express) and 1 railroad specializing in switching and terminals (Talleyrand Terminal).9 The largest operator in the State is CSX Transportation, which owns more than 53 percent of the statewide track mileage. In 2008, Florida’s railroads carried nearly 1.6 million carloads – 19 percent less than in 2006 – and approximately 83 million tons of freight, representing a 25 million ton (23 percent) decrease from 2006.10 During that year, railroads handled freight equivalent to roughly 5.0 million heavy trucks.11 Nonetheless, railroads continue to support thousands of jobs throughout the State and assist Florida’s industries to remain competitive with international and domestic markets for fertilizer, construction rock, consumer goods, paper products, processed 9 U.S. Class I Railroads are line-haul freight railroads with 2007 operating revenue in excess of $359.6 million (2006 operating revenues exceeding $346.7 million). -

House of Representatives Final Bill Analysis Summary

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FINAL BILL ANALYSIS BILL #: CS/CS/CS/HB 695 FINAL HOUSE FLOOR ACTION: SUBJECT/SHORT South Florida Regional 111 Y’s 6 N’s TITLE Transportation Authority SPONSOR(S): Government Accountability Committee; Transportation & Tourism Appropriations GOVERNOR’S Subcommittee; Transportation & Approved ACTION: Infrastructure Subcommittee; Santiago COMPANION CS/CS/SB 842 BILLS: SUMMARY ANALYSIS CS/CS/CS/HB 695 passed the House on April 28, 2017, and subsequently passed the Senate on May 1, 2017. The bill addresses insurance liability issues related to the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA), which operates commuter rail service in Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami-Dade Counties. The bill provides SFRTA with the ability to indemnify the Florida East Coast Railway (FECR) and All Aboard Florida (AAF) under certain circumstances. The bill provides who is responsible for property damage and injury to certain persons associated with several scenarios involving rail accidents. The bill also provides an allocation of risk between the parties and includes provisions for passengers and other rail corridor invitees. The bill authorizes SFRTA to purchase railroad liability insurance of $295 million per occurrence, and allows it to adjust the limit in accordance with applicable law. The bill also requires SFRTA to maintain a $5 million self- insurance retention account. The bill authorizes the Department of Transportation (DOT) to indemnify and insure certain rail services on DOT-owned rail corridors. The bill prohibits SFRTA from entering into a contract or other agreement, or renewing or extending any existing contract or other agreement, which may be funded, in whole or in part, with DOT provided funds without DOT’s prior review and written approval of SFRTA’s proposed expenditures. -

The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Volume XXXII October, 1953 Number 2 The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY CONTENTS The Florida, Atlantic and Gulf Central Railroad Paul E. Fenlon The Election of 1876 in Florida Gov. Marcellus L. Stearns (ed. by) Edward C. Williamson Spanish Interest in British Florida Mark F. Boyd & Jose N. Latorre Book Reviews: Pettingill, “Story of the Florida Railroads” Dorothy Dodd Graff, “Mandarin on the St. Johns” Dena Snodgrass Sitterson, “Sugar Country” J. E. Dovell Wilgus (ed.) “The Caribbean” Ione S. Wright Aguilera (ed.) “Handbook of Latin American Studies” Marshall K. Powers Newman, “Indian River History” Southern Historical Association in Jacksonville Historical Association of Southern Florida The Florida Historical Society New members SUBSCRIPTION FOUR DOLLARS SINGLE COPIES ONE DOLLAR (Copyright, 1953, by the Florida Historical Society. Reentered as second class matter November 21, 1947, at the post office at Tallahassee, Florida, under the Act of August 24, 1912.) Office of publication, Tallahassee, Florida Published quarterly by THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Gainesville, Florida THE FLORIDA, ATLANTIC AND GULF CENTRAL R. R. THE FIRST RAILROAD IN JACKSONVILLE by PAUL E. FENLON Though the factors responsible for the failure of Florida to ex- perience the rapid economic development which took place in the vast western areas of the United States during the latter half of the nineteenth century are numerous and diverse, lack of ade- quate railroad transportation, certainly until the 1880’s, stands out as one of the most important. Midway in the nineteenth century there was not in operation a single mile of railroad in the entire State of Florida. 1 Further- more, the development of railroad transportation facilities that did take place during most of the remainder of the century was spo- radic and relatively unplanned. -

2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan

final report 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan prepared for Florida Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Charles River Associates June 2005 final report 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan prepared for Florida Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Charles River Associates Inc. June 2005 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 Purpose........................................................................................................................... ES-1 Florida’s Rail System.................................................................................................... ES-2 Freight Rail and the Florida Economy ....................................................................... ES-7 Trends and Issues.......................................................................................................... ES-15 Future Rail Investment Needs .................................................................................... ES-17 Strategies and Funding Opportunities ...................................................................... ES-19 Recommendations........................................................................................................ -

Tri-Rail 2013 On-Board Survey

TRI-RAIL 2013 ON-BOARD SURVEY Prepared for: July 2013 South Florida Regional Transportation Authority 800 NW 33rd Street Pompano Beach, FL 33064 Prepared by: HNTB Corporation 8700 West Flagler Street, Suite 402 Miami, FL 33174 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Scope of the Effort ........................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Previous Tri-Rail Surveys .................................................................................................. 3 2.0 SURVEY DESIGN ............................................................................................. 4 2.1 Sampling Plan ................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Survey Instrument ............................................................................................................ 7 2.2.1 Overview / Comparison to Previous Survey Results ................................................................................ 7 2.2.2 Pretest ...................................................................................................................................................... 8 3.0 MINIMIZATION/MITIGATION OF NON-RESPONSE BIAS ................................. 9 4.0 IMPLEMENTATION ....................................................................................... 10 4.1 Training .......................................................................................................................... -

Brightline on Time Unique, Data-Based Maintenance Program Guarantees 100-Percent Availability

Siemens helps keep Brightline on time Unique, data-based maintenance program guarantees 100-percent availability. usa.siemens.com/mobility Travelers arrive on time and relaxed when they take Brightline between West Palm “This is a very modern train. Everything is Beach, Ft. Lauderdale, and Miami. The higher speed passenger rail service relies being monitored and data is being collected on Venture trainsets built and maintained by Siemens Mobility to give people a on anything that is happening, be it a normal event or fault.” smarter way to travel in South Florida. Comprehensive maintenance performed by highly skilled Siemens technicians, who use proven solutions and the latest in Tom Rutkowski digital monitoring and analysis, helps keep the fleet running on schedule every day. VP of Engineering and Chief Mechanical Officer Client Objectives Brightline Brightline envisioned offering the ultimate passenger experience when it partnered with Siemens on the custom design of its five Venture trainsets. It also wanted to ensure on-time travel to make the train a real alternative to car trips bogged down by South Florida’s intense highway traffic. As manufacturing on the first trainset began in July 2015, Brightline recognized that a cutting-edge maintenance program would be crucial to keeping its trains on schedule. It would also be necessary to keep all five of its initial trainsets in running order during service hours. To ensure this high level of availability, Brightline signed a 30-year agreement to make Siemens its maintenance partner for the long term. Brightline began revenue service in January 2018. The maintenance program was up and running by then, operating out of a renovated depot in West Palm Beach that was updated to meet the special requirements of quick turnaround service. -

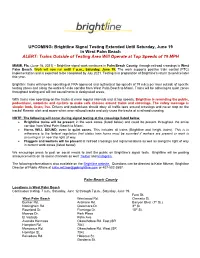

UPCOMING: Brightline Signal Testing Extended Until Saturday, June 19 in West Palm Beach ALERT: Trains Outside of Testing Area Will Operate at Top Speeds of 79 MPH

UPCOMING: Brightline Signal Testing Extended Until Saturday, June 19 in West Palm Beach ALERT: Trains Outside of Testing Area Will Operate at Top Speeds of 79 MPH MIAMI, Fla. (June 18, 2021) – Brightline signal work continues in Palm Beach County, through railroad crossings in West Palm Beach. Work will now run until 7 p.m., Saturday, June 19. The work supports positive train control (PTC) implementation and is expected to be completed by July 2021. Testing is in preparation of Brightline’s return to service later this year. Brightline trains will now be operating at FRA approved and authorized top speeds of 79 miles per hour outside of specific testing zones and along the entire 67-mile corridor from West Palm Beach to Miami. Trains will be adhering to quiet zones throughout testing and will not sound horns in designated areas. With trains now operating on the tracks at more regular intervals and at top speeds, Brightline is reminding the public, pedestrians, motorists and cyclists to make safe choices around trains and crossings. The safety message is simple: look, listen, live. Drivers and pedestrians should obey all traffic laws around crossings and never stop on the tracks! Remain alert and aware when near railroad tracks and only cross the tracks at a railroad crossing. NOTE: The following will occur during signal testing at the crossings listed below: • Brightline trains will be present in the work zones (listed below) and could be present throughout the entire corridor from West Palm Beach to Miami. • Horns WILL SOUND, even in quiet zones. This includes all trains (Brightline and freight trains). -

“From Bone Valley to 'Far Places': a Global Environmental History of The

Edward D. Melillo – Please do no cite or copy without author’s permission “From Bone Valley to ‘Far Places’: A Global Environmental History of the 1919 Phosphate Miners’ Strike in Mulberry, Florida” Edward Melillo, Amherst College Introduction In her 1942 autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, writer Zora Neale Hurston vividly depicted the miners of Polk County, Florida, their “sweating black bodies, muscled like gods…. They go down in the phosphate mines and bring up the wet dust of the bones of pre-historic monsters, to make rich land in far places, so that people can eat.”1 Hurston’s narrative suspended readers between the immediacy of sinew and bone and the remoteness of the “far places” that reconstituted their soils with fertilizer from Florida’s phosphorus-rich fossil deposits. Among the sites where Hurston gathered folklore for the Works Projects Administration (WPA) in the late 1930s was the town of Mulberry, thirty-two miles (52 km) east of Tampa in Polk County. This railroad outpost in Florida’s “Bone Valley” region—a zone where phosphate-laden skeletons accumulated millions of years ago when much of the area was beneath the ocean—has long been a place where the gritty labors of a southern community converged with the demands of distant environments.2 This article chronicles a 1919 strike during which 3,000 black and white miners from the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers targeted seventeen of 1 Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road: An Autobiography (1942; New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 147. 2 On May 6, 1935, United States President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the WPA by Executive Order #7034. -

2018 Demographics Report By

2018 Demographics Report by: Applied Research & Analytics Nicholas Martinez, AICP Urban Economics & Market Development, Senior Manager Kathryn Angleton Research & GIS Coordinator Miami Downtown Development Authority 200 S Biscayne Blvd Suite 2929 Miami, FL 33131 Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………..2 Greater Downtown Miami…………………………………..3 Population…………………………………………………………..4 Population Growth…………………………………....4 Population Distribution……………………………..5 Age Composition………………………………………............6 Households………………………………………....................10 Household Growth…………………………………....10 Trends………………………………………..................10 Local Context……………………………………….................12 Population and Households……………………….12 Employment and Labor……………………………..13 Daytime Population…………………………………..14 Metropolitan Context………………………………………….16 Population and Households……………………….17 Employment and Labor……………………………...18 Daytime Population…………………………………..20 Cost of Living……………………………………………..22 Migration……………………………………….......................24 Income………………………………………...........................25 Educational Attainment……………………………………….26 Pet Ownership………………………………………................28 Exercise………………………………………..........................29 Appendix………………………………………........................30 Metropolitan Areas……………………………………31 Florida Cities………………………………………........32 Greater Downtown & Surrounding Areas…..33 Downtown Miami……………………………………...34 Sources………………………………………………………………..35 Executive Summary Florida Florida is the third most populous state with over 19.9 million people. Within