Formaldehyde and Nitrogen Dioxide Over the Remote Western Pacific Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formaldehyde? Formaldehyde Is a Colorless, Strong-Smelling Gas Used to Make Household Products and Building Materials, Furniture, and Paper Products

What is formaldehyde? Formaldehyde is a colorless, strong-smelling gas used to make household products and building materials, furniture, and paper products. It is used in particleboard, plywood, and fiberboard. What products contain formaldehyde? Formaldehyde can be found in most homes and buildings. Formaldehyde is also released into the air from many products you may use in your home. Because formaldehyde breaks down in air, you may breathe it in from such products as • carpet cleaner • gas cookers and open fireplaces, • cosmetics, • glue, • fabric softeners, • household cleaners, and • fingernail polish and hardeners, • latex paint. Burning cigarettes and other tobacco products also release formaldehyde. Products give off different amounts of formaldehyde. For example, • fingernail polish gives off more formaldehyde than do plywood and new carpet, and • some paper products—such as grocery bags and paper towels—give off only small amounts of formaldehyde. Our bodies even produce some formaldehyde, although only in small amounts. Will I get sick if I breathe or touch formaldehyde? You might not get sick if you breathe or touch formaldehyde, but if you have breathed or touched formaldehyde you may have symptoms such as • sore, itchy, or burning eyes, nose, or throat; • skin rash; or • breathing symptoms such as chest tightness, coughing, and shortness of breath. People who are more likely to get sick from being around formaldehyde are children, the elderly, and people with asthma. Formaldehyde may affect children more than it does adults. If you think your child may have been around formaldehyde, and he or she has symptoms contact a doctor. You should also know that: babies are not likely to get formaldehyde from breast milk, and you may be more sensitive to formaldehyde if you have asthma. -

Method 323—Measurement of Formaldehyde Emissions from Natural Gas-Fired Stationary Sources—Acetyl Acetone Derivitization Method

While we have taken steps to ensure the accuracy of this Internet version of the document, it is not the official version. Please refer to the official version in the FR publication, which appears on the Government Printing Office's FDSys website (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collectionCfr.action?). Method 323—Measurement of Formaldehyde Emissions From Natural Gas-Fired Stationary Sources—Acetyl Acetone Derivitization Method 1.0 Introduction. This method describes the sampling and analysis procedures of the acetyl acetone colorimetric method for measuring formaldehyde emissions in the exhaust of natural gas-fired, stationary combustion sources. This method, which was prepared by the Gas Research Institute (GRI), is based on the Chilled Impinger Train Method for Methanol, Acetone, Acetaldehyde, Methyl Ethyl Ketone, and Formaldehyde (Technical Bulletin No. 684) developed and published by the National Council of the Paper Industry for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. (NCASI). However, this method has been prepared specifically for formaldehyde and does not include specifications (e.g., equipment and supplies) and procedures (e.g., sampling and analytical) for methanol, acetone, acetaldehyde, and methyl ethyl ketone. To obtain reliable results, persons using this method should have a thorough knowledge of at least Methods 1 and 2 of 40 CFR part 60, appendix A–1; Method 3 of 40 CFR part 60, appendix A–2; and Method 4 of 40 CFR part 60, appendix A–3. 1.1 Scope and Application 1.1.1 Analytes. The only analyte measured by this method is formaldehyde (CAS Number 50–00–0). 1.1.2 Applicability. This method is for analyzing formaldehyde emissions from uncontrolled and controlled natural gas-fired, stationary combustion sources. -

Toxicological Profile for Formaldehyde

TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE FOR FORMALDEHYDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry July 1999 FORMALDEHYDE ii DISCLAIMER The use of company or product name(s) is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. FORMALDEHYDE iii UPDATE STATEMENT Toxicological profiles are revised and republished as necessary, but no less than once every three years. For information regarding the update status of previously released profiles, contact ATSDR at: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Toxicology/Toxicology Information Branch 1600 Clifton Road NE, E-29 Atlanta, Georgia 30333 FORMALDEHYDE vii QUICK REFERENCE FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS Toxicological Profiles are a unique compilation of toxicological information on a given hazardous substance. Each profile reflects a comprehensive and extensive evaluation, summary, and interpretation of available toxicologic and epidemiologic information on a substance. Health care providers treating patients potentially exposed to hazardous substances will find the following information helpful for fast answers to often-asked questions. Primary Chapters/Sections of Interest Chapter 1: Public Health Statement: The Public Health Statement can be a useful tool for educating patients about possible exposure to a hazardous substance. It explains a substance’s relevant toxicologic properties in a nontechnical, question-and-answer format, and it includes a review of the general health effects observed following exposure. Chapter 2: Health Effects: Specific health effects of a given hazardous compound are reported by route of exposure, by type of health effect (death, systemic, immunologic, reproductive), and by length of exposure (acute, intermediate, and chronic). -

1.0 Introduction. This Method Describes the Sampling and Analysis Procedures of the Acetyl Acetone Colorimetric Method For

Method 323 8/7/2017 While we have taken steps to ensure the accuracy of this Internet version of the document, it is not the official version. To see a complete version including any recent edits, visit: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/ECFR?page=browse and search under Title 40, Protection of Environment. METHOD 323—MEASUREMENT OF FORMALDEHYDE EMISSIONS FROM NATURAL GAS-FIRED STATIONARY SOURCES—ACETYL ACETONE DERIVITIZATION METHOD 1.0 Introduction. This method describes the sampling and analysis procedures of the acetyl acetone colorimetric method for measuring formaldehyde emissions in the exhaust of natural gas-fired, stationary combustion sources. This method, which was prepared by the Gas Research Institute (GRI), is based on the Chilled Impinger Train Method for Methanol, Acetone, Acetaldehyde, Methyl Ethyl Ketone, and Formaldehyde (Technical Bulletin No. 684) developed and published by the National Council of the Paper Industry for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. (NCASI). However, this method has been prepared specifically for formaldehyde and does not include specifications (e.g., equipment and supplies) and procedures (e.g., sampling and analytical) for methanol, acetone, acetaldehyde, and methyl ethyl ketone. To obtain reliable results, persons using this method should have a thorough knowledge of at least Methods 1 and 2 of 40 CFR part 60, appendix A-1; Method 3 of 40 CFR part 60, appendix A-2; and Method 4 of 40 CFR part 60, appendix A-3. 1.1 Scope and Application 1.1.1 Analytes. The only analyte measured by this method is formaldehyde (CAS Number 50- 00-0). 1.1.2 Applicability. -

WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality : Selected Pollutants

WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: This book presents WHO guidelines for the protection of pub- lic health from risks due to a number of chemicals commonly present in indoor air. The substances considered in this review, i.e. benzene, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, naphthalene, nitrogen dioxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (especially benzo[a]pyrene), radon, trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethyl- ene, have indoor sources, are known in respect of their hazard- ousness to health and are often found indoors in concentrations of health concern. The guidelines are targeted at public health professionals involved in preventing health risks of environmen- SELECTED CHEMICALS SELECTED tal exposures, as well as specialists and authorities involved in the design and use of buildings, indoor materials and products. POLLUTANTS They provide a scientific basis for legally enforceable standards. World Health Organization Regional Offi ce for Europe Scherfi gsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Tel.: +45 39 17 17 17. Fax: +45 39 17 18 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.euro.who.int WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: selected pollutants The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health, Bonn Office, WHO Regional Office for Europe coordinated the development of these WHO guidelines. Keywords AIR POLLUTION, INDOOR - prevention and control AIR POLLUTANTS - adverse effects ORGANIC CHEMICALS ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURE - adverse effects GUIDELINES ISBN 978 92 890 0213 4 Address requests for publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for per- mission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). -

Formaldehyde

Poison Facts: High Chemicals: Formaldehyde Properties of the Chemical Formaldehyde is a colorless gas at ordinary temperatures. It has a pungent, suffocating odor. The chemical is very reactive and combines readily with many substances. It is miscible with water, acetone, benzene, diethyl ether, chloroform and ethanol. Formalin is a solution of about 37 percent formaldehyde by weight in water, usually with 10 to 15 percent methanol added to prevent polymerization. This solution is full-strength and also known as Formalin 100 percent or Formalin 40, which signifies that it contains 40 grams of formaldehyde within 100 ml of the solution. Uses of the Chemical Formaldehyde is used in fertilizers, insecticides, germicides, fungicides, herbicides, sewage treatment, paper-making preservatives, embalming fluids, disinfectants, ureaformaldehyde resins, foam insulation, industrial and soil Stalinist, urea and melamine resins, polyacetal and phenolic resins, artificial silk and cellulose esters, dye fasteners, explosives, latex-backed fabrics, particle board, plywood, air fresheners, cosmetics, wet fingernail hardeners and polishes, antimicrobial hair shampoos and conditioners, water-based paints, chemicals for tanning and preserving hides, and as a chemical intermediate. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion (ADME) Formaldehyde is rapidly absorbed by ingestion and inhalation. Delayed absorption of methanol might occur following ingestion of formalin if the formaldehyde causes fixation of the stomach. Based on studies, very little formaldehyde is absorbed through the dermal route. In all cases, absorption appears to be limited to cell layers immediately adjacent to the point of contact. Formaldehyde is rapidly metabolized to formic acid, largely in the liver by the catalytic action of alcohol dehydrogenase and to a lesser extent in erythrocytes in the brain, kidney and muscles. -

Sources of Formaldehyde in Bountiful, Utah

atmosphere Article Sources of Formaldehyde in Bountiful, Utah Nitish Bhardwaj 1, Ariel Kelsch 1, Delbert J. Eatough 1, Ryan Thalman 2 , Nancy Daher 3, Kerry Kelly 4 , Isabel Cristina Jaramillo 4 and Jaron C. Hansen 1,* 1 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] (N.B.); [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (D.J.E.) 2 Department of Chemistry, Snow College, Richfield, UT 84701, USA; [email protected] 3 Utah Division of Air Quality, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, USA; [email protected] 4 Chemical Engineering, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (I.C.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-801-422-4066 Abstract: The U.S Environmental Protection Agency’s National Air Toxics Trends Stations Network has been measuring the concentration of hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) including formaldehyde (HCHO) since 2003. Bountiful, Utah (USA) has served as one of the urban monitoring sites since the network was established. Starting in 2013, the mean concentration of HCHO measured in Bountiful, Utah exceeded the non-cancer risk threshold and the 1 in 1 million cancer risk threshold. In addition, the measured concentrations were more than double those found at surrounding locations in Utah. A Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) analysis using PMF-EPA v5 was performed using historical data (2004–2017) to better understand the sources of formaldehyde in the region. The historical data set included samples that were collected every sixth day on a 24 h basis. -

Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde 50-00-0 Hazard Summary Formaldehyde is used mainly to produce resins used in particleboard products and as an intermediate in the synthesis of other chemicals. Exposure to formaldehyde may occur by breathing contaminated indoor air, tobacco smoke, or ambient urban air. Acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) inhalation exposure to formaldehyde in humans can result in respiratory symptoms, and eye, nose, and throat irritation. Limited human studies have reported an association between formaldehyde exposure and lung and nasopharyngeal cancer. Animal inhalation studies have reported an increased incidence of nasal squamous cell cancer. EPA considers formaldehyde a probable human carcinogen (Group B1). Please Note: The main sources of information for this fact sheet are EPA's Health and Environmental Effects Profile for Formaldehyde (1) and the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) (6), which contains information on oral chronic toxicity and the RfD, and the carcinogenic effects of formaldehyde including the unit cancer risk for inhalation exposure. Uses Formaldehyde is used predominantly as a chemical intermediate. It also has minor uses in agriculture, as an analytical reagent, in concrete and plaster additives, cosmetics, disinfectants, fumigants, photography, and wood preservation. (1,2) One of the most common uses of formaldehyde in the U.S is manufacturing urea-formaldehyde resins, used in particleboard products. (7) Formaldehyde (as urea formaldehyde foam) was extensively used as an insulating material until 1982 when it was banned by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (1,2) Sources and Potential Exposure The highest levels of airborne formaldehyde have been detected in indoor air, where it is released from various consumer products such as building materials and home furnishings. -

Synthesis and Investigation of Sulfonated Acetone-Formaldehyde

2nd International Conference on Electronic & Mechanical Engineering and Information Technology (EMEIT-2012) Synthesis and investigation of sulfonated acetone-formaldehyde polycondensate as dispersant for coal-water slurry Junfeng Zhu∗a, Guanghua Zhangb, Junguo Lic, Fang Zhaod, Qianqian Que Key Laboratory of Additives of Chemistry & Technology for Chemical Industry, Ministry of Education; College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Shaanxi University of Science & Technology, Xi'an 710021, China aemail:[email protected](corresponding author), bemail:[email protected], cemail:[email protected], demail: [email protected], eemail:[email protected] Keywords: sulfonated acetone–formaldehyde(SAF), dispersant, coal-water slurry (CWS), application Abstract. According to the literature preparation process, sulfonated acetone - formaldehyde polycondensate (SAF) was prepared with different mole ratio of formaldehyde (F) and acetone (A). Its structure was characterized by IR and TGA. SAF was applied in the Shenhua coal-water slurry (CWS). And the slurryability and stability of the CWS were tested using the viscometer. Wetting performance of SAF dispersant on the surface of coal was studied via video contact angle. The SAF, synthesized with the mole ratio of formaldehyde and acetone at 2.2, performances best in Shenhua coal-water slurry. The SAF is a promising dispersants for Shenhua coal after it was optimized. Under 65 wt% of the coal concentration and 0.45 wt% of the dosage of dispersant, the viscosity of CWS is 476 m Pa • s at the shear rate of 100s-1, the 7 days separating water ratio is 4.63 v/v%, and wetting properties of SAF is better than water on the coal surface. -

Effects of Post-Manufacture Board Treatments on Formaldegyde Emission

Effects of post-manufacture board treatments on formaldehyde emission: a literature review (1960-1984) George E. Myers treatments. At present I suggest that impregnation of Abstract boards with aqueous solutions (Method 1) is likely to be This paper reviews the literature dealing with the the most reliable because it should permit the use of a many post-manufacture board treatments used to re large scavenger excess and also allow neutralization of duce formaldehyde emission from urea-formaldehyde board acidity to reduce resin hydrolysis. bonded boards. Such treatments have almost solely used one or more of five chemical or physical principles: 1) formaldehyde reaction with NH3, 2) formaldehyde reaction with oxygenated sulfur compounds, 3) formal This is the fifth in a planned series of six critical dehyde reaction with organic -NH functionality, 4) pH reviews of the literature on different aspects of the adjustment, and 5) physical barrier. I have categorized problem of formaldehyde emission from adhesively the available reports according to four primary board bonded wood products. The series was initiated at the treatment methods that use the five principles in differ Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wis., in response ent ways. The four primary treatment methods are: to a need expressed by industry representatives for an 1. Application of scavengers as solids or aqueous independent evaluation and summation of data from solutions. Ammonium bicarbonate and carbonate have diverse sources. The six aspects being reviewed concern been used as solid powders, while the solutions involved the effects of formaldehyde-to-urea mole ratio (F/U) a variety of ammonium salts, ammonium and alkali (48), ventilation rate and loading (49), temperature and metal salts with sulfur-containing anions, and urea and humidity (51), separate additions to wood furnish or other compounds having -NH functionality; veneer (52), post-manufacture treatments of boards, 2. -

FIXATION with FORMALDEHYDE- ACETONE Materials

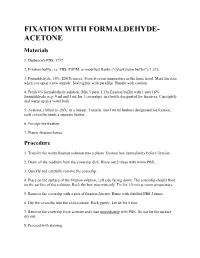

FIXATION WITH FORMALDEHYDE- ACETONE Materials 1. Dulbecco's PBS, 37oC. 2. Fixation buffer, i.e. PBS, PHEM, or modified Hanks ("cytoskeleton buffer"), 1.33x. 3. Formaldehyde, 16%, EM Sciences. Store at room temperature in the fume hood. Mark the date when you open a new ampule. Seal tightly with parafilm. Handle with caution. 4. Fresh 4% formaldehyde solution. Mix 3 parts 1.33x fixation buffer with 1 part 16% formaldehyde (e.g. 9 ml and 3 ml for 1 coverslip), in a bottle designated for fixatives. Cap tightly and warm up in a water bath. 5. Acetone, chilled to -20oC in a freezer. Transfer into 100 ml beakers designated for fixation, each coverslip needs a separate beaker. 6. Forceps for fixation. 7. Plastic fixation boxes. Procedure 1. Transfer the warm fixation solution into a plastic fixation box immediately before fixation. 2. Drain all the medium from the coverslip dish. Rinse out 2 times with warm PBS. 3. Quickly and carefully remove the coverslip. 4. Place on the surface of the fixation solution, cell side facing down. The coverslip should float on the surface of the solution. Rock the box intermittently. Fix for 10 min at room temperature. 5. Remove the coverslip with a pair of fixation forceps. Rinse with distilled PBS 2 times. 6. Dip the coverslip into the cold acetone. Rock gently. Let sit for 5 min. 7. Remove the coverslip from acetone and rinse immediately with PBS. Do not let the surface dry out. 8. Proceed with staining. 9. Used acetone should be emptied into a designated container. -

Substance Technical Guideline for Formaldehyde Use with the Formaldehyde Rule, Chapter 296-856 WAC

Notes Substance Technical Guideline for Formaldehyde Use with the Formaldehyde Rule, Chapter 296-856 WAC This helpful tool is a guideline for both: • General information about formaldehyde exposure and • Specific information about Formaldehyde solution called Formalin. – Formaldehyde is most commonly used as formalin, which is a solution that contains 37% formaldehyde in water. When exposure is from resins capable of releasing formaldehyde, the resin itself and other impurities or decomposition products may also be toxic. You should be aware of the hazards associated with all materials you handle. Specific information and guidance about formaldehyde are outlined in this helpful tool under the following topics: – Formaldehyde Health Effects – Formaldehyde Technical Data Sheet – Exposure monitoring – Exposure controls – Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) – Spills and Other Emergencies – Emergency First Aid Response Resources 1•800•4BE SAFE (1•800•423•7233) http://www.lni.wa.gov/ R-3 09/06 06/09 Substance Technical Guideline for Formaldehyde Substance Technical Guideline for Formaldehyde Use with the Formaldehyde Rule, Chapter 296-856 WAC Use with the Formaldehyde Rule, Chapter 296-856 WAC FORMALDEHYDE HEALTH EFECTS Both acute and chronic exposures to formaldehyde can cause adverse health effects. Acute Exposures • Acute exposures generally consist of single exposures to high concentrations of formaldehyde, which may occur during an uncontrolled spill or release of formaldehyde gas. • Acute formaldehyde exposure effects are shown in Table