Bipolar Depression: a Major Unsolved Challenge Ross J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAP-MD-05 GLYX13-C-203 Protocol Amendment 3 Final-R

NCT02192099 Study ID: GLYX13‐C‐203 Title: Open Label Extension for Subjects with Inadequate/Partial Response to Antidepressants during the Current Episode of Major Depressive Disorder Previously Treated with Rapastinel (GLYX‐13) (Extension of GLYX13‐C‐202, NCT01684163) Protocol Amendment 3 Date: 23 Nov 2016 Clinical Study Protocol Protocol Number: GLYX13-C-203 Study Drug: Rapastinel (GLYX-13) Injection (rapastinel Injection) FDA ID: 107,974 Clinicaltrials.gov: Title: Open Label Extension for Subjects with Inadequate/Partial Response to Antidepressants during the Current Episode of Major Depressive Disorder Previously Treated with Rapastinel (GLYX-13) (Extension of GLYX13-C-202, NCT01684163) Study Phase: 2 Sponsor: Naurex, Inc, an affiliate of Allergan, plc. Date: Amendment 3 dated 23 November 2016 Replaces Amendment 2 dated 20 January 2015 This document is a confidential communication from Naurex, Inc, an affiliate of Allergan, plc.. Acceptance of this document constitutes an agreement by the recipient(s) that no information contained herein will be published or disclosed without prior written approval from Allergan, plc., except that this document may be disclosed to appropriate Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) under the condition that they are also required to maintain confidentiality. Naurex, Inc, an affiliate of Allergan, plc. Protocol GLYX13-C-203 INVESTIGATOR SIGNATURE PAGE The signature of the investigator below constitutes his/her approval of this protocol and provides the necessary assurances that this study will be conducted according to all stipulations of the protocol as specified in both the clinical and administrative sections, including all statements regarding confidentiality. This trial will be conducted in compliance with the protocol and all applicable regulatory requirements, in accordance with Good Clinical Practices (GCPs), including International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Guidelines, and in general conformity with the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki. -

Poster Session III, December 6, 2017

Neuropsychopharmacology (2017) 42, S476–S652 © 2017 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/17 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Poster Session III a high-resolution research tomograph (HRRT), and struc- Palm Springs, California, December 3–7, 2017 tural (T1) MRI using a 3-Tesla scanner. PET data analyses were carried out using the validated 2-tissue compartment Sponsorship Statement: Publication of this supplement is model to determine the total volume of distribution (VT) of sponsored by the ACNP. [18F]FEPPA. Individual contributor disclosures may be found within the Results: Results show significant inverse associations (con- abstracts. Part 1: All Financial Involvement with a pharma- trolling for rs6971 genotype) between neuroinflammation ceutical or biotechnology company, a company providing (VTs) and cortical thickness in the right medial prefrontal clinical assessment, scientific, or medical products or compa- cortex [r = -.562, p = .029] and the left dorsolateral nies doing business with or proposing to do business with prefrontal cortex [r = -.629, p = .012](p values are not ACNP over past 2 years (Calendar Years 2014–Present); Part 2: corrected for multiple comparisons). No significant associa- Income Sources & Equity of $10,000 per year or greater tions were found with surface area. (Calendar Years 2014 - Present): List those financial relation- Conclusions: These results, while preliminary, suggest links ships which are listed in part one and have a value greater than between the microglial activation/neuroinflammation and $10,000 per year, OR financial holdings that are listed in part cortical thickness in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and one and have a value of $10,000 or greater as of the date of medial prefrontal cortex in AD patients. -

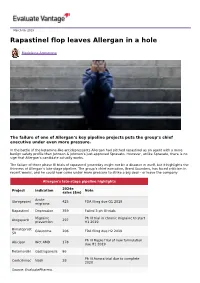

Rapastinel Flop Leaves Allergan in a Hole

March 06, 2019 Rapastinel flop leaves Allergan in a hole Madeleine Armstrong The failure of one of Allergan’s key pipeline projects puts the group’s chief executive under even more pressure. In the battle of the ketamine-like antidepressants Allergan had pitched rapastinel as an agent with a more benign safety profile than Johnson & Johnson’s just-approved Spravato. However, unlike Spravato, there is no sign that Allergan’s candidate actually works. The failure of three phase III trials of rapastinel yesterday might not be a disaster in itself, but it highlights the thinness of Allergan’s late-stage pipeline. The group’s chief executive, Brent Saunders, has faced criticism in recent weeks, and he could now come under more pressure to strike a big deal – or leave the company. Allergan's late-stage pipeline highlights 2024e Project Indication Note sales ($m) Acute Ubrogepant 425 FDA filing due Q1 2019 migraine Rapastinel Depression 359 Failed 3 ph III trials Migraine Ph III trial in chronic migraine to start Atogepant 297 prevention H1 2019 Bimatoprost Glaucoma 206 FDA filing due H2 2019 SR Ph III Maple trial of new formulation Abicipar Wet AMD 178 due H1 2019 Relamorelin Gastroparesis 86 Ph III Aurora trial due to complete Cenicriviroc Nash 28 2020 Source: EvaluatePharma. Activist shareholders have long been agitating for change at Allergan, and the latest failure will only provide more ammunition to those who want to split the roles of chairman and chief exec amid dissatisfaction with the group's acquisition strategy, and with its stock hovering around a five-year low. -

WO 2017/066590 Al 20 April 2017 (20.04.2017) P O P CT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/066590 Al 20 April 2017 (20.04.2017) P O P CT (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 38/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/519 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61 38/07 (2006.0V) A61K 31/551 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, A61K 31/13 (2006.01) A61K 31/5513 (2006.01) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, A61K 31/135 (2006.01) A61P 25/24 (2006.01) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, A61K 31/496 (2006.01) A61P 25/18 (2006.01) HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US20 16/057071 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, 14 October 2016 (14.10.201 6) TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, zw. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, 62/242,633 16 October 2015 (16. -

Gottlieb's Shock Resignation Leaves Ripples in the Industry

15 March 2019 No. 3946 Scripscrip.pharmaintelligence.informa.com Pharma intelligence | informa time, which is difficult. He also used the office in a “forward-leaning way” not seen often. “He kind of drove the conversation through very good communication exter- nally,” Myers said. “He was able to use a lot of the ideas percolating in the agency, pack- age them and get them moved forward.” Gottlieb pushed FDA to the forefront of the drug pricing debate, a position the agency had not sought in the past. In his first speech to staff after confir- mation, he said that even though the agency cannot set drug prices, it can promote competition. Gottlieb was vocal in chastising the brand industry for blocking generic Credit: FDA Credit: competition, warning that Congress could make more drastic changes if it did not stop employing pay-for-delay and licensing tactics intended to pre- Gottlieb’s Shock Resignation vent patent challenges. (Also see “Got- tlieb: Real Risk Of Congressional Action If Leaves Ripples In The Industry Anti-Competitive Actions Continue” - Pink Sheet, 3 May, 2018.) DERRICK GINGERY [email protected] He also publicly released a list of com- panies thought to be using the Risk Evalu- S FDA Commissioner Scott Gott- being apart from my family for these past ation and Mitigation Strategy system to lieb, one of the most popular and two years and missing my wife and three prevent generic companies from purchas- Uvisible commissioners in decades, young children.” ing samples for testing, although it is not will end his tenure as head of FDA in about clear the move had much impact. -

Sustained Antidepressant Action of the N‑Methyl‑D‑Aspartate Receptor Antagonist MK‑801 in a Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Model

5376 EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 16: 5376-5383, 2018 Sustained antidepressant action of the N‑methyl‑D‑aspartate receptor antagonist MK‑801 in a chronic unpredictable mild stress model BANG-KUN YANG1, JUN QIN2, YING NIE3 and JIN-CAO CHEN1 1Department of Neurosurgery, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei 430071; Departments of 2Neurosurgery and 3Children's Medical Center, Taihe Hospital, Hubei University of Medicine, Shiyan, Hubei 442600, P.R. China Received December 29, 2016; Accepted November 29, 2017 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2018.6876 Abstract. (5S,10R)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo(A,D) mice. Therefore, the present study revealed the sustained cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate (MK-801) is antidepressant effects of MK-801 in the CUMS model. an N-methyl-D-aspartate non-competitive antagonist that Furthermore, synaptogenesis and neuronal regeneration in the possesses useful biological properties, including anticon- prelimbic regions of mPFC, DG and CA3 of the hippocampus vulsant and anesthetic activities. Studies have indicated the may be implicated as mechanisms that promote a sustained rapid antidepressant effects of MK-801 in animal models. antidepressant response. However, there are no reports concerning a sustained anti- depressant effect in the chronic unpredictable mild stress Introduction (CUMS) model. Furthermore, the antidepressant mechanism remains unclear. The aim of the present study was to examine In addition to being the most prevalent mental disorder, the effects of MK-801 (0.1 mg/kg) and rapastinel (10 mg/kg) depression is one of the leading causes of disability across on depression-like behavior in CUMS mice and measure the world (1). -

24Hrs Patent Application Publication May 21 , 2020 Sheet 1 of 6 US 2020/0155522 A1

US 20200155522A1 IN (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No.: US 2020/0155522 A1 Osten et al. (43 ) Pub . Date : May 21 , 2020 (54 ) GABOXADOL FOR REDUCING RISK OF Publication Classification SUICIDE AND RAPID RELIEF OF (51 ) Int. Ci. DEPRESSION A61K 31/437 (2006.01 ) A61K 31/135 (2006.01 ) ( 71) Applicant: Certego Therapeutics , Farmingdale , A61P 25/24 ( 2006.01 ) NY (US ) (52 ) U.S. CI. (72 ) Inventors: Pavel Osten , Brooklyn , NY (US ) ; CPC A61K 31/437 (2013.01 ) ; A61P 25/24 Kristin Baldwin , San Diego , CA (US ) ( 2018.01 ) ; A61K 31/135 ( 2013.01 ) (73 ) Assignee : Certego Therapeutics, Farmingdale , ( 57 ) ABSTRACT NY (US ) Methods and compositions are disclosed for rapidly reduc (21 ) Appl. No.: 16 /691,049 ing the risk of suicide in patients suffering from acute suicidality and rapidly relieving mood symptoms in major ( 22 ) Filed : Nov. 21 , 2019 depression and treatment - resistant depression using a novel therapeutic regimen comprising a single or intermittent Related U.S. Application Data administration of a high dose of gaboxadol, or a pharma (60 ) Provisional application No.62 / 770,287 , filed on Nov. ceutically acceptable salt thereof, to the subject n need 21 , 2018 . thereof. 220 I ther 24hrs Patent Application Publication May 21 , 2020 Sheet 1 of 6 US 2020/0155522 A1 FIGURE1:METHODFORWHOLE-BRAINPHARMACOMAPSREPRESENTINGDRUGEVOKED ACTIVATIONINTHEMOUSE. Patent Application Publication May 21 , 2020 Sheet 2 of 6 US 2020/0155522 A1 FIGURE 2 : KETAMINE DOSE - CURVE PHARMACOMAPS , Ketamine -

Exploring Hallucinogen Pharmacology and Psychedelic Medicine with Zebrafish Models

ZEBRAFISH Volume 13, Number 5, 2016 Review Articles ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/zeb.2016.1251 Exploring Hallucinogen Pharmacology and Psychedelic Medicine with Zebrafish Models Evan J. Kyzar1 and Allan V. Kalueff2–6 Abstract After decades of sociopolitical obstacles, the field of psychiatry is experiencing a revived interest in the use of hallucinogenic agents to treat brain disorders. Along with the use of ketamine for depression, recent pilot studies have highlighted the efficacy of classic serotonergic hallucinogens, such as lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin, in treating addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety. However, many basic phar- macological and toxicological questions remain unanswered with regard to these compounds. In this study, we discuss psychedelic medicine as well as the behavioral and toxicological effects of hallucinogenic drugs in zebrafish. We emphasize this aquatic organism as a model ideally suited to assess both the potential toxic and therapeutic effects of major known classes of hallucinogenic compounds. In addition, novel drugs with hal- lucinogenic properties can be efficiently screened using zebrafish models. Well-designed preclinical studies utilizing zebrafish can contribute to the reemerging treatment paradigm of psychedelic medicine, leading to new avenues of clinical exploration for psychiatric disorders. Introduction requiring the use of both traditional (rodent) and novel model species.6 In this study, we briefly review the history of psy- allucinogenic drugs have been used by humans for chedelic medicine and the pharmacology of these drugs and centuries, exerting potent effects on thought, cognition, H discuss the effects of hallucinogenic drugs on larval and adult and behavior with little propensity for habit formation and zebrafish (Danio rerio). -

Ketamine and Beyond: Investigations Into the Potential of Glutamatergic Agents to Treat Depression

Drugs DOI 10.1007/s40265-017-0702-8 REVIEW ARTICLE Ketamine and Beyond: Investigations into the Potential of Glutamatergic Agents to Treat Depression 1 1 1 Marc S. Lener • Bashkim Kadriu • Carlos A. Zarate Jr Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland (outside the USA) 2017 Abstract Clinical and preclinical studies suggest that dysfunction of the glutamatergic system is implicated in Key Points mood disorders such as major depressive disorder and bipolar depression. In clinical studies of individuals with This review highlights evidence supporting the major depressive disorder and bipolar depression, rapid antidepressant effects of subanesthetic-dose reductions in depressive symptoms have been observed in ketamine as a prototypical glutamatergic-modulating response to subanesthetic-dose ketamine, an agent whose agent from which other glutamatergic agents have mechanism of action involves the modulation of gluta- been investigated. matergic signaling. The findings from these studies have prompted the repurposing and/or development of other Evidence suggests that ketamine may have broad glutamatergic modulators for antidepressant efficacy, both biological effects on the glutamatergic system and as monotherapy or as an adjunct to conventional may exert its clinical efficacy by altering other monoaminergic antidepressants. This review highlights symptom domains related to depression, such as the evidence supporting the antidepressant effects of anxiety and suicidality. subanesthetic-dose ketamine as well as other glutamatergic This review also highlights important safety modulators, such as D-cycloserine, riluzole, CP-101,606, concerns regarding ketamine and selected CERC-301 (previously known as MK-0657), basimglurant, glutamatergic agents to promote the continued JNJ-40411813, dextromethorphan, nitrous oxide, GLYX- development of novel, effective, and safe 13, and esketamine. -

Towards Rapid-Acting Treatments for OCD

Towards Rapid-Acting Treatments for OCD C AR O LY N R ODRIGUEZ , M . D . , P H .D. A SSISTANT P ROFESSOR OF P SYCHIATRY AND B EHAVIORAL S CIENCES S TANFORD U NIVERSITY S CHOOL OF M EDICINE 1 Funding and Disclosures (Rapastinel) Study Drug: Rapastinel (formerly GLYX-13) was supplied by Naurex at no cost (since drug donation Naurex has been acquired by Allergan) Funding: 2014 NARSAD Ellen Schapiro and Gerald Axelbaum Young Investigator Award, Brain and Behavior Research (PI: Rodriguez) New York Presbyterian Youth Anxiety Center K24MH9155 (PI: Simpson) K23MH092434 (PI: Rodriguez) Dr. Rodriguez was reimbursed for time and travel to present these findings at Allergan after submitting for publication. Dr. Moskal founder and owned stock in Naurex. Dr. Burch was an employee of Naurex when rapastinel was donated. 2 Funding and Disclosures NIMH (PI: Rodriguez) . K23 Novel Interventions for Adults with OCD . R01 NMDAR Modulation As A Therapeutic Target and Probe of Neural Dysfunction in OCD Foundations/Donors (PI: Rodriguez) . Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Award, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation . 2009 & 2014 NARSAD, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation . Black Family, Graham Arader, Youth Anxiety Center Initiative Other (PI: Rodriguez) . New York State Office of Mental Health . Provost’s Grants Award Program . Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Industry (Consultant: Rodriguez) . Allergan . Rugen Therapeutics . BlackThorn Therapeutics 3 OCD: A Chronic, Disabling Disorder 2% Lifetime prevalence Half of cases start by age 19 Only FDA-approved medication: Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors Koran et al., 2007; Koran and Simpson 2013 Koran et al., 2007; Koran and Simpson, 2013 4 Imagine you are on a hike… 5 …but the only water lies in a toilet bowl. -

Top 5 Issues Clinicians Should Know About Ketamine Therapy

Top 5 Issues Clinicians Should Know about Ketamine Therapy Sanjay J. Mathew, MD Marjorie Bintliff Johnson and Raleigh White Johnson, Jr. Vice Chair for Research Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Baylor College of Medicine Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center Houston, Texas Faculty Disclosure • Dr. Mathew: Consultant—Alkermes, Allergan, Clexio Biosciences, Intracellular Therapies, Janssen, Perception Neurosciences, Sage Therapeutics; Grant/Research Support—Biohaven, VistaGen Therapeutics. Disclosure • The faculty have been informed of their responsibility to disclose to the audience if they will be discussing off-label or investigational use(s) of drugs, products, and/or devices (any use not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration). – Ketamine does not have an FDA-approved indication for any psychiatric disorder. • Applicable CME staff have no relationships to disclose relating to the subject matter of this activity. • This activity has been independently reviewed for balance. Learning Objectives • Assess the clinical trials literature on the use of ketamine and esketamine for treatment-resistant depression • Describe leading hypotheses as to how ketamine and esketamine is working in the brain • Apply this learning to the individual patient in order to assess the risks vs the benefits of this therapy Outline #1. FDA Approval of Intranasal Esketamine for TRD #2. Methods to Prolong and Extend the Short-Lived Effect #3. Comparative Effectiveness in TRD #4. Mechanism -

Lääkeaineiden Yleisnimet (INN-Nimet) 21.6.2021

Lääkealan turvallisuus- ja kehittämiskeskus Säkerhets- och utvecklingscentret för läkemedelsområdet Finnish Medicines Agency Lääkeaineiden yleisnimet (INN-nimet) 21.6.