Cardiac Monitoring in Patients with Electrocution Injury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurological and Neurourological Complications of Electrical Injuries

REVIEW ARTICLE Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska Polish Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgery 2021, Volume 55, no. 1, pages: 12–23 DOI: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2020.0076 Copyright © 2021 Polish Neurological Society ISSN 0028–3843 Neurological and neurourological complications of electrical injuries Konstantina G. Yiannopoulou1, Georgios I. Papagiannis2, 3, Athanasios I. Triantafyllou2, 3, Panayiotis Koulouvaris3, Aikaterini I. Anastasiou4, Konstantinos Kontoangelos5, Ioannis P. Anastasiou6 1Neurological Department, Henry Dunant Hospital Centre, Athens, Greece 2Orthopaedic Research and Education Centre “P.N. Soukakos”, Biomechanics and Gait Analysis Laboratory “Sylvia Ioannou”, “Attikon” University Hospital, Athens, Greece 31st Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece 4Medical School of Athens, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece 51st Department of Psychiatry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Eginition Hospital, Athens, Greece 61st Urology Department, Laiko Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece ABSTRACT Electrical injury can affect any system and organ. Central nervous system (CNS) complications are especially well recognised, causing an increased risk of morbidity, while peripheral nervous system (PNS) complications, neurourological and cognitive and psychological abnormalities are less predictable after electrical injuries. PubMed was searched for English language clinical observational, retrospective, -

Case Report Myelopathy and Amnesia Following Accidental Electrical Injury

Spinal Cord (2002) 40, 253 ± 255 ã 2002 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/sc Case Report Myelopathy and amnesia following accidental electrical injury J Kalita*,1, M Jose1 and UK Misra1 1Department of Neurology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences Lucknow, India Objective: Documentation of MRI and neurophysiological changes following accidental electrical injury. Setting: Tertiary care referral teaching hospital at Lucknow, India. Results: A 30-year-old lady developed amnesia and spastic paraparesis with loss of pin prick sensation below the second thoracic spinal segment following electrocution. Her spinal MRI was normal and cranial MRI revealed T2 hyperintensity in the right putamen. Peroneal, sural and electromyography were normal. Tibial central sensory conduction time was normal but central motor conduction time to lower limbs and right upper limb was prolonged. Conclusion: Neurophysiological study and MRI may help in understanding the pathophy- siological basis of neurological sequelae following electrical injury. Spinal Cord (2002) 40, 253 ± 255. DOI: 10.1038/sj/sc/3101275 Keywords: electrical injury; MRI; evoked potential; myelopathy; amnesia Introduction Rural electri®cation has received great attention from across the road. Her hands were wet, the road was the government for improving agricultural and small ¯ooded with water and the wire was conducting AC of scale industry development in India. This has inherent 11 000 V. Immediately, she had fallen down and the hazards because of the ignorance of villagers and poor wire stuck to her chest. The current ¯ow was maintenance of electrical cables. This results in several discontinued after about 5 min and she was discovered electrical accidents caused by the touching of live wires. -

Instructor Guide for Tactical Field Care 3C Communication, Evacuation Prioroties and Cpr 180801 1

INSTRUCTOR GUIDE FOR TACTICAL FIELD CARE 3C COMMUNICATION, EVACUATION PRIOROTIES AND CPR 180801 1 Tactical Combat Casualty Care for Medical Personnel August 2017 Next, we will discuss communication, evacuation priorities, and 1. (Based on TCCC-MP Guidelines 170131) CPR in TFC. Tactical Field Care 3c Communication, Evacuation Priorities and CPR Disclaimer “The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed 2. as official or as reflecting the views of the Departments Read the text. of the Army, Air Force, Navy or the Department of Defense.” - There are no conflict of interest disclosures. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Terminal Learning Objective • Communicate combat casualty care items effectively in Tactical Field Care. Enabling Learning Objectives 3. Read the text. • Identify the importance and techniques of communication with a casualty in Tactical Field Care. • Identify the importance and techniques of communicating casualty information with unit tactical leadership. INSTRUCTOR GUIDE FOR TACTICAL FIELD CARE 3C COMMUNICATION, EVACUATION PRIOROTIES AND CPR 180801 2 LEARNING OBJECTIVES Enabling Learning Objectives • Identify the importance and techniques of communicating casualty information with evacuation assets or receiving facilities. 4. Read the text. • Identify the relevant tactical and casualty data involved in communicating casualty information. • Identify the evacuation urgencies recommended in the TCCC TACEVAC “Nine Rules of Thumb” and the JTS evacuation guidelines • Identify the information requirements and format of the 9-Line MEDEVAC Request. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Terminal Learning Objective • Describe cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) considerations in Tactical Field Care. Enabling Learning Objectives 5. Read the text. • Identify considerations for cardiopulmonary resuscitation in tactical field care. -

Guidelines for BLS/ALS Medical Providers Current As of March 2019

Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) Guidelines for BLS/ALS Medical Providers Current as of March 2019 DIRECT THREAT CARE (DTC) / HOT ZONE Guidelines: 1. Mitigate any immediate threat and move to a safer position (e.g. initiate fire attack, coordinated ventilation, move to safe haven, evacuate from an impending structural collapse, etc). Recognize that threats are dynamic and may be ongoing, requiring continuous threat assessments. 2. Direct the injured first responder to stay engaged in the operation if able and appropriate. 3. Move patient to a safer position: a. Instruct the alert, capable patient to move to a safer position and apply self-aid. b. If the patient is responsive but is injured to the point that he/she cannot move, a rescue plan should be devised. c. If a patient is unresponsive, weigh the risks and benefits of an immediate rescue attempt in terms of manpower and likelihood of success. Remote medical assessment techniques should be considered to identify patients who are dead or have non-survivable wounds. 4. Stop life threatening external hemorrhage if present and reasonable depending on the immediate threat, severity of the bleeding and the evacuation distance to safety. Consider moving to safety prior to application of the tourniquet if the situation warrants. a. Apply direct pressure to wound, or direct capable patient to apply direct pressure to own wound and/or own effective tourniquet. b. Tourniquet application: i. Apply the tourniquet as high on the limb as possible, including over the clothing if present. ii. Tighten until cessation of bleeding and move to safety. -

Electrocution Death: Exit Mark Injury Use in the Suggestion of Body Posture During Forensic Investigation

Electrocution Death: Exit Mark Injury use in the Suggestion of Body Posture during Forensic Investigation Pudji Hardjanto1,4 Simon Martin Manyanza Nzilibili1,3 Ahmad Yudianto1,2 1Forensic Science Program, Post Graduate School Universitas Airlangga, 4-6 Airlangga Rd., 60286 Surabaya – Indonesia. 2Department of Forensic and Medico-legal, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya – Indonesia 3Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender Elderly and Children, Dodoma – Tanzania. 4Criminal Investigative Unit, Polrestabes Surabaya, Indonesia. Keywords: Body Posture, Electrocution, Exit Injury, Forensic Reconstruction Abstract: Since then, electrocution and forensic investigation of electric death associated with criminal offenses have established the importance of mark injuries. The marks (entry and exit) came into significance as they were/are used to establish fatality and extent of electric power electrocuted. Unlike entry, exit injury has presented attention to scientists on its adequate and vital use in explaining forensic incident despite being infrequent. To enrich forensic understanding and make use of this “silent witness – exit mark”, this study used four cases of related scenario. Three of the four cases were literature-based cases and one case involved in investigation. By interpreting the cases, this paper argued that exit injury contains useful information that can be related to posture of the body before electrocution. This paper thereby suggested the presence of the exit injury to be related to body posture, sole plantar exit injury in particular (stood position). This would help investigators and scientists to determine the immediate probable position and state of victim before electrocution. Furthermore, the suggestion would assist reconstruction processes that seek to find out the event originality through responding to fundamental and core principle tools of incidence investigation, CoPRRR, and the 6Ws. -

Electrical Injuries: a Review for the Emergency Clinician Czuczman AD, Zane RD

7ddekdY_d]0 <DGI8:K@:< >L@;<C@E<JLG;8K< M`j`k nnn%\Yd\[`Z`e\%e\k&^l`[\c`e\j kf[Xp]fipfli ]i\\jlYjZi`gk`fe Electrical Injuries: A Review October 2009 Volume 11, Number 10 For The Emergency Clinician Authors Amanda Dumler Czuczman, MD As usual, the emergency department is hopping. Two minutes before change Harvard Medical School, The Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals, Boston, MA of shift, a trauma patient rolls in—an electrician in his mid-30s brought in by his coworkers. The patient, who was found unconscious near the genera- Richard D. Zane, MD tor he was repairing, is awake and alert but amnesic, with burns over his Vice Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School chest and both arms. His vital signs are within normal limits. A number of Peer Reviewers management questions enter your mind, including the need for a cardiac Mary Ann Cooper, MD evaluation and hospital admission. As you begin formulating a plan, the Emerita Professor, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL nurse tells you that a young woman has arrived after “getting shocked” by her hair dryer, which she was using while standing on a wet bathroom floor. Brian J. Daley, MD, MBA, FACS Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of She has no obvious injuries or complaints other than very mild erythema Tennessee Medical Center at Knoxville, Knoxville, TN of her right palm. The nurse asks if you want to order an ECG or send any CME Objectives blood tests. Upon completion of this article, you should be able to: It is unusual to have 2 electrical injuries in a single night. -

Neuropsychological, Psychological, and Injury Variables Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Individuals Who Suffered an Electrical Injury

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Neuropsychological, Psychological, and Injury Variables Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Individuals Who Suffered an Electrical Injury Jana Wingo Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wingo, Jana, "Neuropsychological, Psychological, and Injury Variables Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Individuals Who Suffered an Electrical Injury" (2013). Dissertations. 695. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/695 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Jana Wingo LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL, AND INJURY VARIABLES ASSOCIATED WITH POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN INDIVIDUALS WHO SUFFERED AN ELECTRICAL INJURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDICACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY BY JANA WINGO CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Jana Wingo, 2013 All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all of the people who made this dissertation possible, starting with the psychologists who helped guide my research. Dr. Fred Bryant provided me with a background in statistics and introduced me to the wonders of classification tree analysis using Optimal Data Analysis. Dr. Duke Han instigated my interest in traumatic brain injury and fostered my pursuit of neuropsychology. -

Therapeutic Hypothermia with Progesterone Improves Neurologic Outcomes in Ventricular Fibrillation Cardiac Arrest After Electric Shock

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.15749 Therapeutic Hypothermia With Progesterone Improves Neurologic Outcomes in Ventricular Fibrillation Cardiac Arrest After Electric Shock Fred N. Qafiti 1 , David Rubay 2 , Rebecca Shin 3 , Lawrence Lottenberg 4 , Robert Borrego 5 1. General Surgery, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, USA 2. Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, USA 3. Surgery, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, USA 4. Surgery, St. Mary's Medical Center, Florida Atlantic University, West Palm Beach, USA 5. Surgery, St. Mary's Medical Center, West Palm Beach, USA Corresponding author: David Rubay, [email protected] Abstract Trauma by electricity imposes mechanical, electrical, and thermal forces on the human body. Often, the delicate cardiac electrophysiology is disrupted causing dysrhythmia and subsequent cardiac arrest. Anoxic brain injury (ABI) is the most severe consequence and the main cause of mortality following cardiac arrest. Establishing a working protocol to treat patients who are at risk for ABI after suffering a cardiac arrest is of paramount importance. There has yet to be sufficient exploration of combination therapy of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) and progesterone as a neuroprotective strategy in patients who have suffered cardiac arrest after electric shock. The protocol required TH initiation upon transfer to the ICU with a target core body temperature of 33°C for 18 hours. This was achieved through a combination of cooling blankets, ice packs, chilled IV fluids, nasogastric lavage with iced saline, and intravascular cooling devices. Progesterone therapy at 80-100 mg intramuscularly every 12 hours for 72 hours was initiated shortly after admission to the ICU. -

TRAUMA RESUSCITATION: Triage/Trauma Team Activation

PRACTICE GUIDELINE: TRAUMA RESUSCITATION: Triage/Trauma Team Activation OBJECTIVE: To ensure timely triage, assessment and collaborative management of the injured patient, trauma team activation will be conducted according to the following process: GUIDELINES: Trauma Level I: Major Trauma Resuscitation Patients meeting the following criteria should be seen in the resuscitation room. Trauma Team activation should occur upon notification by EMS or upon patient arrival in the resuscitation room with immediate response of the Trauma Team. The ED Clinical Coordinator will call the “Trauma Group Alert” on the Nextel Direct phone. 1. Systolic BP < 90 2. Respiratory rate < 10 or > 30 3. Glasgow coma score 10 4. Intubation in the field or respiratory compromise 5. Intubations prior to transfer from outside facilities 6. GSW to head, neck, trunk, including buttocks and perineum 7. Resuscitative blood transfusion during transport 8. ED Senior Staff Physician Discretion Trauma Level II: Trauma Resuscitation Patients meeting the following criteria may benefit from initial evaluation in the resuscitation room. The patient can be directed into the resuscitation room upon pre- hospital EMS notification or otherwise the ED triage nurse will make the determination upon arrival whether to place the patient in the resuscitation room. The Trauma team should be activated for all Level II patients in the resuscitation room. The ED Clinical Coordinator will call the “Trauma Group Alert”. All other LEVEL II patients who are not immediately placed in the resuscitation room by the ED triage nurse will be evaluated in triage by an ED Staff Physician. The ED triage nurse will call the CAT 1 ED Staff physician who must come to triage to assess the patient and subsequently determine the acuity and appropriate course of care. -

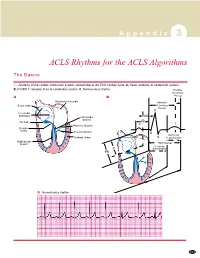

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Neurofeedback in the Reduction Of

Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 2015, Vol 22, No 3, 556–563 www.aaem.pl ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evaluation of the effectiveness of neurofeedback in the reduction of Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a patient following high-voltage electric shock with the use of ERPs Anna Chrapusta1, Maria Pąchalska2,3, Magdalena Wilk-Frańczuk4, Małgorzata Starczyńska5, Juri D. Kropotov6,7 1 Małopolska Burns and Plastic Surgery Centre, The Rydygier Memorial Hospital, Krakow, Poland 2 Chair of Neuropsychology, Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski Krakow University, Krakow, Poland 3 Center for Cognition and Communication, New York, NY, USA 4 Department of Health Sciences, Vincent Pol University Lublin, Poland 5 Department of Health Sciences, The Jan Kochanowski University, Kielce, Poland 6 The Institute of the Human Brain, The Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia 7 The Institute of Psychology, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway Chrapusta A, Pąchalska M, Wilk-Frańczuk M, Starczyńska M, Kropotov JD. Evaluation of the effectiveness of neurofeedback in the reduction of Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a patient following high-voltage electric shock with the use of ERPs. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015; 22(3): 556–563. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1167734 Abstract Background. The aim of our research was an evaluation of the effectiveness of neurofeedback in reducing the symptoms of Post-trauma stress disorder (PTSD), which had developed as a result of a high-voltage electric burn to the head. Quantitative EEG (QEEG) and Event related potentials (ERPs) were utilised in the evaluation. Case study. A 21-year-old patient, experienced 4th degree burns to his head as a result of a high-voltage electric burn. -

Allyson Hammond

The Physics of Electrocution Allyson Hammond UPII Honors Project Section H2 Introduction The field of physics encompasses a broad area of knowledge, and thus has far reaching effects. The physiology of the human body is one such topic. With approximately 1,000 people dying each year in the United States due to electrocution and approximately 3,000 patients who survive being admitted to specialized burn units (Spies), understanding both the physics behind electricity and its effects on human physiology is a worthwhile undertaking. Electrical injuries can be very complex so recognizing the mechanisms involved requires a firm comprehension of how electricity works, how the electrical components of the body work in a normal state, and how outside sources of electricity affect change the ordinary physiology. Electricity Just like water flows from a region of higher pressure to a region of lower pressure, electrons flow across a potential gradient from high electron concentration to low concentration (Spies). This is called electricity. The potential difference created is represented by volts (V) and is the driving force of the electrons. The amount of electrons flowing, or the volume, is known as the current. The amount of current is designated by amperes. Resistance (R) is defined as any impedance to flow. All of these concepts are related using Ohm’s law. Ohm’s law. Ohm’s law says that the amount of current is equal to the ratio of the voltage and resistance (Kuphaldt): 푉 퐼 = 푅 There are two designated types of current: alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) (Jain). DC currents are those in which electricity moves in a continuous direction around a circuit (Kuphaldt).