Status of Galliformes in Pipar Pheasant Reserve and Santel, Annapurna, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Alectoris Chukar

PEST RISK ASSESSMENT Chukar partridge Alectoris chukar (Photo: courtesy of Olaf Oliviero Riemer. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons Attribution License, Version 3.) March 2011 This publication should be cited as: Latitude 42 (2011) Pest Risk Assessment: Chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar). Latitude 42 Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd. Hobart, Tasmania. About this Pest Risk Assessment This pest risk assessment is developed in accordance with the Policy and Procedures for the Import, Movement and Keeping of Vertebrate Wildlife in Tasmania (DPIPWE 2011). The policy and procedures set out conditions and restrictions for the importation of controlled animals pursuant to s32 of the Nature Conservation Act 2002. For more information about this Pest Risk Assessment, please contact: Wildlife Management Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Address: GPO Box 44, Hobart, TAS. 7001, Australia. Phone: 1300 386 550 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au Disclaimer The information provided in this Pest Risk Assessment is provided in good faith. The Crown, its officers, employees and agents do not accept liability however arising, including liability for negligence, for any loss resulting from the use of or reliance upon the information in this Pest Risk Assessment and/or reliance on its availability at any time. Pest Risk Assessment: Chukar partridge Alectoris chukar 2/20 1. Summary The chukar partridge (Alectoris chukar) is native to the mountainous regions of Asia, Western Europe and the Middle East (Robinson 2007, Wikipedia 2009). Its natural range includes Turkey, the Mediterranean islands, Iran and east through Russia and China and south into Pakistan and Nepal (Cowell 2008). -

Notable Bird Records from Mizoram in North-East India (Forktail 22: 152-155)

152 SHORT NOTES Forktail 22 (2006) Notable bird records from Mizoram in north-east India ANWARUDDIN CHOUDHURY The state of Mizoram (21°58′–24°30′N 92°16′–93°25′E) northern Mizoram, in March 1986 (five days), February is located in the southern part of north-east India (Fig. 1). 1987 (seven days) and April 1988 (5 days) while based in Formerly referred to as the Lushai Hills of southern Assam, southern Assam. During 2–17 April 2000, I visited parts it covers an area of 21,081 km2. Mizoram falls in the Indo- of Aizawl, Kolasib, Lawngtlai, Lunglei, Mamit, Saiha, Burma global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and Serchhip districts and surveyed Dampa Sanctuary and the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area and Tiger Reserve, Ngengpui Willdlife Sanctuary, (Stattersfield et al. 1998). The entire state is hilly and Phawngpui National Park and the fringe of Khawnglung mountainous. The highest ranges are towards east with Wildlife Sanctuary. This included 61 km of foot transect the peaks of Phawngpui (2,157 m; the highest point in along paths and streams, 2.5 km of boat transects along Mizoram) and Lengteng (2,141 m). The lowest elevation, the Ngengpui River and Palak Dil, and 1,847 km of road <100 m, is in the riverbeds near the borders with Assam transects. During 15–22 February 2001, I visited parts of and Bangladesh border. The climate is tropical monsoon- type with a hot wet summer and a cool dry winter. Table 1. Details of sites mentioned in the text. Temperatures range from 7° to 34°C; annual rainfall ranges from 2,000 to 4,000 mm. -

A Note on Artificial Regeneration of Acacia

The Pakistan Journal of Forestry Vol.63(2), 2013 STATUS AND CONSERVATION OF PHEASANTS IN KAGHAN VALLEY Mian Muhammad Shafiq1 and Muhammad Saqib2 ABSTRACT Pheasants are considered the most beautiful birds in the world. Out of 49 species of pheasant found in the world five species i.e. Monal, (Lophoporus impejanus) koklass (Pucrasia macrolopha), Kalij (Lophura leucomelana), western horned Tragopan (Gragopan melanocephalus) and Cheer (Catreus wallichi) are found in Pakistan while four (4) species i.e. Monal, Koklass, Kalij and Western horned Tragopan are found in the study areas of Kaghan valley. This study was conducted in the Kaghan valley to know the status and conservation of pheasants. A questionnaire was designed and the villages were selected which were located near the reserve forest. A sample of 60 persons were interviewed in detail. The study revealed that the climate and topography of target area provides good habitat to pheasants, but impediments such as illegal hunting, poaching and human interference are the main causes for the decline in population. However declaration of some areas of the Kaghan valley as protected area (National park and wildlife sanctuary) has considerably contributed in the increase of pheasant population. The major earthquake in 2005 in the area had considerably decreased the population of pheasants as well as it has damaged the habitat of pheasants. It is recommended that there should be control on deforestation, habitat improvement and awareness raising campaign should also be carried out. INTRODUCTION Pheasants are the gallinaceous birds with beautiful, brilliant, multicolored and highly ornamental plumage. (Shah, 1987). Within the order Galliformes the pheasants comprise a very huge family with over 16 Genera amongst which there are 49 distinct species and sub species (13 occurring in sub continent) (IUCN, 1998). -

Faunal Diversity of Kitchen Gardens of Sikkim

Eco. Env. & Cons. 26 (November Suppl. Issue) : 2020; pp. (S29-S35) Copyright@ EM International ISSN 0971–765X Faunal diversity of Kitchen Gardens of Sikkim Aranya Jha, Sangeeta Jha and Ajeya Jha SMIT (Sikkim Manipal University), Tadong 737 132, Sikkim, India (Received 20 March, 2020; Accepted 20 April, 2020) ABSTRACT What is the faunal richnessof rural kitchen gardensof Sikkim? This was the research question investigated in this study. Kitchen gardens have recently been recognized as important entities for biodiversity conservations. This recognition needs to be backed by surveys in various regions of the world. Sikkim, a Himalayan state of India, in this respect, is important, primarily because it is one of the top 10 biodiversity hot-spots globally. Also because ecologically it is a fragile region. Methodology is based on a survey of 67 kitchen gardens in Sikkim and collecting relevant data. The study concludes that in all 80 (tropical), 74 (temperate) and 17 (sub-alpine) avian species have been reported from the kitchen gardens of Sikkim. For mammals these numbers are 20 (tropical) and 9 (temperate). These numbers are indicative and not exhaustive. Key words : Himalayas, Rural kitchen gardens, Tropical, Temperate, Sub-alpine, Aves, Mammals. Introduction Acharya, (2010). Kitchen gardens and their ecological benefits: Re- Kitchen gardens have been known to carry im- cently ecological issues have emerged as highly sig- mense ecological significance. When we, as a civili- nificant and naturally ecologically important facets zation, witness the ecological crisis that we have such as agricultural lands, mountains, forests, rivers ourselves created we find a collective yearning for and oceans have been identified as critical entities. -

MONITORING PHEASANTS (Phasianidae) in the WESTERN HIMALAYAS to MEASURE the IMPACT of HYDRO-ELECTRIC PROJECTS

THE RING 33, 1-2 (2011) DOI 10.2478/v10050-011-0003-7 MONITORING PHEASANTS (Phasianidae) IN THE WESTERN HIMALAYAS TO MEASURE THE IMPACT OF HYDRO-ELECTRIC PROJECTS Virat Jolli, Maharaj K. Pandit ABSTRACT Jolli V., Pandit M.K. 2011. Monitoring pheasants (Phasianidae) in the Western Himalayas to measure the impact of hydro-electric projects. Ring 33, 1-2: 37-46. In this study, we monitored pheasants abundance to measure the impact of a hydro- electric development project. The pheasants abundance was monitored using “call count” and line transect methods during breeding seasons in 2009-2011. Three call count stations and 3 transects were laid with varying levels of anthropogenic disturbance. To understand how the hydro power project could effect the pheasant population in the Jiwa Valley, we monitored it under two conditions; in the presence of hydro-electric project (HEP) con- struction and when human activity significantly declined. The Koklass Pheasant (Pucrasia macrolopha), Cheer Pheasant (Catreus wallichi) and Western Tragopan (Tragopan melano- cephalus) were not recorded in Manjhan Adit in 2009. During 2010 and 2011 springs, the construction activity was temporarily discontinued in Manjhan Adit. The pheasants re- sponded positively to this and their abundance increased near disturbed sites (Manjhan Adit). The strong response of pheasants to anthropogenic disturbance has ecological appli- cation and thus can be used by wildlife management in the habitat quality monitoring in the Himalayan Mountains. V. Jolli (corresponding author), M.K. Pandit, Centre for Inter-disciplinary Studies of Mountain and Hill Environment, Academic Research Building, Patel Road, Univ. of Delhi, Delhi, India, E-mail: [email protected] Key words: call count, anthropogenic disturbance, pheasant, monitoring, hydro-electric project INTRODUCTION Birds have been used extensively in environment and habitat quality monitoring. -

Distribution Ecology, Habitat Use and Conservation of Chestnut-Breasted Partridge in Thrumshingla National Park

Royal University of Bhutan College of Natural Resources Lobesa DISTRIBUTION ECOLOGY, HABITAT USE AND CONSERVATION OF CHESTNUT-BREASTED PARTRIDGE IN THRUMSHINGLA NATIONAL PARK. In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the of B.Sc. Forestry programme Tashi Dhendup June, 2015 DECLARATION FORM I declare that this is an original work and I have not committed, to my knowledge, any academic dishonesty or resorted to plagiarism in writing the dissertation. All the sources of information and assistance received during the course of the study are duly acknowledged. Student’s Signature: ________________ Date: 13th May, 2015. i Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my Supervisor, Dr. D.B. Gurung, Dean of Academic Affairs, College of Natural Resources, Royal University of Bhutan, for providing his consistent valuable advice and guidance through each stage of the dissertation. I am extremely grateful to the Director General, Department of Forest and Park Services (DoFPS) and Chief Forestry Officer, Thrumshingla National Park (TNP), DoFPS, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests (MoAF) for according approval to carry out the research activity within the protected areas of Bhutan. I earnestly acknowledge to the WWF, Bhutan Program and Oriental Bird Club (OBC), United Kingdom, for funding this study without which it would not have been possible to carry out my research. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to the Director, Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environment (UWICE), Bumthang and Chief Forestry Officer, TNP for rendering the necessary field equipment. My sincere thanks go to Mr. Dorji Wangdi, B.Sc. Forestry, 4th Cohort, College of Natural Resources, for his invaluable help during the data collection and Mr. -

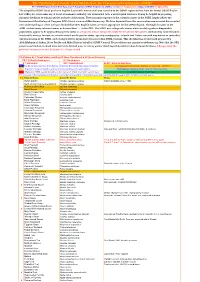

31St August 2021 Name and Address of Collection/Breeder: Do You Closed Ring Your Young Birds? Yes / No

Page 1 of 3 WPA Census 2021 World Pheasant Association Conservation Breeding Advisory Group 31st August 2021 Name and address of collection/breeder: Do you closed ring your young birds? Yes / No Adults Juveniles Common name Latin name M F M F ? Breeding Pairs YOUNG 12 MTH+ Pheasants Satyr tragopan Tragopan satyra Satyr tragopan (TRS ringed) Tragopan satyra Temminck's tragopan Tragopan temminckii Temminck's tragopan (TRT ringed) Tragopan temminckii Cabot's tragopan Tragopan caboti Cabot's tragopan (TRT ringed) Tragopan caboti Koklass pheasant Pucrasia macrolopha Himalayan monal Lophophorus impeyanus Red junglefowl Gallus gallus Ceylon junglefowl Gallus lafayettei Grey junglefowl Gallus sonneratii Green junglefowl Gallus varius White-crested kalij pheasant Lophura l. hamiltoni Nepal Kalij pheasant Lophura l. leucomelana Crawfurd's kalij pheasant Lophura l. crawfurdi Lineated kalij pheasant Lophura l. lineata True silver pheasant Lophura n. nycthemera Berlioz’s silver pheasant Lophura n. berliozi Lewis’s silver pheasant Lophura n. lewisi Edwards's pheasant Lophura edwardsi edwardsi Vietnamese pheasant Lophura e. hatinhensis Swinhoe's pheasant Lophura swinhoii Salvadori's pheasant Lophura inornata Malaysian crestless fireback Lophura e. erythrophthalma Bornean crested fireback pheasant Lophura i. ignita/nobilis Malaysian crestless fireback/Vieillot's Pheasant Lophura i. rufa Siamese fireback pheasant Lophura diardi Southern Cavcasus Phasianus C. colchicus Manchurian Ring Neck Phasianus C. pallasi Northern Japanese Green Phasianus versicolor -

Parasites of Kalij Pheasants (Lophura Leucomelana) on the Island of Hawaii!

Pacific Science (1983), vol. 37, no. 1 © 1983 by the University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Parasites of Kalij Pheasants (Lophura leucomelana) on the Island of Hawaii! VICTOR LEWIN and JEROME L. MAHRT2 ABSTRACT: Kalij pheasants (Lophura leucomelana) were collected from the island of Ha waii from 21 March to 25 June 1981, and were examined for parasites . These introduced forest dwelling pheasants are sympatric with both endangered endemic birds and mosquitoes, which are known vectors of avian malaria. No blood parasites were found in any of the 44 Kalij pheasants ex amined. An eyeworm, Oxyspirura sp., was found in two birds. One pheasant was infested with a body louse Amyrsidea monostoecha, and a feather louse Lagopoecus colchicus was found on two birds. The latter represents a new host record . KALIJ PHEASANTS (Lophura leucomelana) are Scott 1979, Sakai and Ralph 1980), a survey native to the western foothills of the Hima was conducted to determine if Kalij pheasants layas in northern India and Nepal (BohI1971). act as reservoir hosts for pathogens. These gallopheasants were introduced into Hawaii in 1962at the Puu Waawaa Ranch on the island ofHawaii (Lewin 1971)from game METHODS farms in Michigan and Texas. They became established and ultimately spread widely Kalij pheasants were shot between 21 throughforested regions of the island; they March and 25 June 1981. Forty-four pheas now occur extensively in the tree fern-ohia ants from widely separated areas were col koa forests and in exotic forest plantations be lected. Most were from the Kona coast: 36 tween 500 and 1600 meters elevation (Lewin from the Makaula Ooma Forest Reserve; and Lewin 1983). -

Restricted Bird Species List221.04 KB

RESTRICTED BIRD LICENCE CATEGORIES Exempt Birds - If these species are the only birds kept, no permit is required Canary, Common, Serinus canaria Ground-dove, White-bibbed; Pigeon, White- Pigeon, Domestic; Rock Dove, Columba livia breasted Ground; Jobi Island Dove, Gallicolumba jobiensis Cardinal, Red-crested, Paroaria coronata Guineafowl, Helmeted, Numida meleagris Pigeon, Luzon Bleeding Heart, Gallicolumba luzonica Chicken; Domestic Fowl; all bantams; Red Jungle Fowl, Parrotfinch, Red-throated; Red-faced Parrotfinch, Pytilia, Crimson-winged; Aurora Finch, Pytilia Gallus gallus Erythrura psittacea phoenicoptera Duck, domestic breeds only, Anas spp. Peafowl, Common; Indian Peafowl, Pavo cristatus Pytilia, Green-winged; Melba Finch, Pytilia melba Duck, Mallard; Mallard, Anas platyrhynchos Peafowl, Green, Pavo muticus Swan, Mute; White Swan, Cygnus olor Duck, Muscovy, Cairina moschata Pheasant, Golden, Chrysolophus pictus Turkey, Common, Meleagris gallopavo Firefinch, Red-billed, Lagonosticta senegala Pheasant, Himalayan Monal; Impeyan Pheasant, Turtle-Dove, Laughing, Streptopelia senegalensis Lophophorus impejanus Goldfinch; European Goldfinch, Carduelis carduelis Pheasant, Kalij, Lophura leucomelanos Turtle-Dove, Spotted, Streptopelia chinensis Goose, All Domestic Strains, Anser anser Pheasant, Lady Amherst's, Chrysolophus Waxbill, Lavender; Lavender Finch, Estrilda amherstiae caerulescens Goose, Swan; Chinese Goose, Anser cygnoides Pheasant, Reeves's, Syrmaticus reevesii Waxbill, Zebra; Golden-breasted Waxbill; Orange- breasted Waxbill, -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Survey of Western Tragopan, Koklass Pheasant, and Himalayan Monal Populations in the John Corder, World Pheasant Association

60 Indian BIRDS Vol. 6 No. 3 (Publ. 7th August 2010) Survey of Western Tragopan, Koklass Pheasant, and Himalayan Monal populations in the Pheasant Association. World John Corder, Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India Fig. 1. Himalayan Monal Lophophorus Jennifer R. B. Miller impejanus. Miller, J. R. B. 2010. Survey of Western Tragopan, Koklass Pheasant, and Himalayan Monal populations in the Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian BIRDS 6 (3): XXX–XXX. Jennifer R. B. Miller1, Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, 195 Prospect Street, New Haven Connecticut 06511, USA. Email: [email protected] Surveys conducted in the late 1990’s indicated that pheasant populations in the Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India were declining. In 1999, the government legally notified the park and authorities began enforcing the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, banning biomass extraction within park boundaries and reducing human disturbance. Populations of three pheasant species (Western Tragopan, Koklass Pheasant and Himalayan Monal) were subsequently surveyed in the park during the breeding season (April–May) in 2008. Call counts and line transects were used to assess current abundances and gather more information on the characteristics of these species in the wild. Relative abundances of all three species were significantly higher than in previous surveys. Tragopan males began their breeding calls in late April and continued through May whereas Koklass males called consistently throughout the study period. The daily peak calling periods of the two species overlapped, but Tragopan males began calling earlier in the morning than Koklass males. Monals were most often sighted alone or in pairs and larger groups tended to have equal sex composition or a slightly higher number of females than males.