Theparadoxes Ofa Liberal Marxist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule of Law Commodity Derivatives

The rule of law Robert A Stein University of Minnesota Law School The essence of the rule of law, as originally attributed to Aristotle, is a “government by laws and not by men”.1 Scholars, judges and organisations in various countries, particularly in recent years, have laboured to define in greater detail the meaning of this concept.2 There is wide agreement that the concept is difficult to define in a way that captures all of its significant meaning.3 US Supreme Court Justice Anthony M Kennedy has observed: “The term Rule of Law is often invoked yet seldom defined.”4 A good starting point in examining the concept is the definition of the rule of law set forth in the 2004 Report of the Secretary General of the United Nations, entitled The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies: [The rule of law] refers to a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural legal transparency.5 The principles constituting the rule of law identified in this definition are both procedural and substantive. The rule of law principles are procedural, for example, in that the laws must be the supreme law of the land, publicly promulgated, equally enforced, and adjudicated by an independent judiciary. -

4. Mao's Theory of Representation

Theory of Representation: China and the West by Yizhou Sun Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Ruth Grant, Supervisor ___________________________ Thomas Spragens ___________________________ Michael Gillespie Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT Theory of Representation: China and the West by Yizhou Sun Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Ruth Grant, Supervisor ___________________________ Thomas Spragens ___________________________ Michael Gillespie An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v Copyright by Yizhou Sun 2014 Abstract This thesis tries to explore the nature of Chinese Communists’ claim to represent the people. Although China has never established a Western-style representative government based on elections, it has its own theory of representation. By comparing the Chinese theory with the theories about representation of Western thinkers such as the Liberals, Burke, and Rousseau, it can be found that although China’s theory is different from the Liberal views, it has illuminating similarities with Burke’s and Rousseau’s theories. On the other hand, it contains distinctive -

Socialist Sacrilege: the Provocative Contributions of George Bernard

SOCIALIST SACRILEGE: THE PROVOCATIVE CONTRIBUTIONS OF GEORGE BERNARD SHAW AND GEORGE ORWELL TO SOCIALISM IN THE 20TH CENTURY A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Matthew Fleagle August, 2009 SOCIALIST SACRILEGE: THE PROVOCATIVE CONTRIBUTIONS OF GEORGE BERNARD SHAW AND GEORGE ORWELL TO SOCIALISM IN THE 20TH CENTURY Matthew Fleagle Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________ __________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Alan Ambrisco Dr. Chand Midha __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Hillary Nunn Dr. George R. Newkome __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Date Mr. Robert Pope __________________________ Department Chair Dr. Michael Schuldiner ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. THE TRICKLE-DOWN SOCIALISM OF SHAW .......................................................1 Works Cited ..........................................................................................................42 II. THE RADICAL AMONG REVOLUTIONARIES .....................................................43 Works Cited ..........................................................................................................79 III. MARXIST COLLECTIVISM AND THE LITERARY AESTHETIC ......................81 Works Cited ........................................................................................................105 iii CHAPTER I THE TRICKLE-DOWN -

Alert-2-Authoritarian-Dark-Triad.Pdf

Beware the Beast The Authoritarian Dark Triad & the Dolphin Defense Strategy By Robert Porter Lynch (Version 1.1 updated Feb 2017) (not for publication!) We are in difficult times with a disturbing re-emergence of Authoritarianism throughout the world. Recently I have spoken with leaders from Europe and North America and often the discussion gravitated to one of the most disturbing issues since the rise of the Nazis and Communists in the 1930s. Leaders in Britain, Holland, France, and Austria are seeing a new breed of Authoritarians assuming prominent positions in government. Much of this is the result of a precipitous drop in trust in institutions across Western civilization. Leaders with a conscience need to understand why this is happening, and how to respond. Considerable research has been done in the seventy years after the end of the Second World War to understand what happened with the rise of people like Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini. The personalities of these leaders are an amalgamation of two highly disconcerting personality drives: 1. “Authoritarians” who are also 2. “Dark”(represented by what is termed the “dark triad,” consisting of Narcissists, Machiavellians, and Psychopaths – each of which will be discussed below). Authoritarians Thrive in the Power Game Why Authoritarians Arise Authoritarians will always be in our midst – it’s part of the natural dispersion of character types. Because the authoritarian’s mind is so convinced their ideas (or vision or values or assessment) is correct and right, those who are either confused, simplistic, of similar belief, or intellectually disengaged will be attracted to the authoritarian. -

A Brief History of the Political Line of the Communist Workers Group (Marxist-Leninist)

A Brief History of the Political Line of the Communist Workers Group (Marxist-Leninist) The Communist Workers Group (Marxist-Leninist) [CWG] joined the public polemics within the anti-revisionist, Marxist-Leninist movement in the United States in June 1975. The occasion was publication of Our Tasks On The National Question: Against Nationalist Deviations In Our Movement [Our Tasks]. In the three to four years prior, the group had developed along lines similar to the rest of what has become known as the New Communist Movement [NCM]. The small group sprang from the mass democratic, anti-war and anti-imperialist struggles of the 1960s. The individual organizers and, later, theoreticians of the CWG began to study Marxism-Leninism [ML] to more clearly understand these movements, the domestic and international economic and political situation and class forces at play during the early 1970s. As the movement developed, their study of ML was instrumental in sorting out all the contending political lines purporting to represent “true” communist leadership. The CWG considered itself to be fully within the ideological parameters of the ML movement. The group upheld Marxism-Leninism as the scientific method of studying, analyzing and understanding social relations. It, therefore, viewed the class struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie and for the dictatorship of the proletariat as the motive force of history in all stages of capitalist development. The CWG further located the origins of modern revisionism within the CPSU and the CPUSA as well as cohort parties around the world, and acknowledged the leading role of the Communist Party of China [CP China] and the Party of Labor of Albania [PLA] in the international struggle against this revisionism. -

Glasnost| the Pandora's Box of Gorbachev's Reforms

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1999 Glasnost| The Pandora's box of Gorbachev's reforms Judy Marie Sylvest The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sylvest, Judy Marie, "Glasnost| The Pandora's box of Gorbachev's reforms" (1999). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2458. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2458 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Tlie University of IVTONXANA Permission is granted by the autlior to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature ri a nh^ YYla LjJl£rt' Date .esmlyPYJ ?> ^ / ? ? Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. GLASNOST: THE PANDORA'S BOX OF GORBACHEV'S REFORMS by Judy Marie Sylvest B.A. The University of Montana, 1996 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 1999 Approved by: //' Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP34448 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

How to Understand, and Deal with Dictatorship: an Economist's View

Econ. Gov. (2001) 2: 35–58 c Springer-Verlag 2001 How to understand, and deal with dictatorship: an economist’s view Ronald Wintrobe Professor of Economics and Co-Director, Political Economy Research Group, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario N6A5C2, Canada Received: February 1999 / Accepted: 10 November 1999 Abstract. This paper explains in simple English some of the main ideas about autocracy first developed elsewhere (e.g., in my book, The Political Economy of Dictatorship (Cambridge University Press, 1998). I use rational choice theory to explain the behavior of dictatorships and develop policy toward them. Issues discussed in this paper include: How do successful regimes stay in power? What determines the repressiveness of a regime? Which type of regime redistributes more, dictatorship or democracy? Can dictatorships be good for economic growth and efficiency? The starting point of my analysis is The Dictator’s Dilemma- the insecurity every dictator necessarily experiences about how much support he really has. Because of this, the dictator finds that the tool of repression is not enough to maintain his regime, and successful dictators typically rule with the loyal support of at least some groups of subjects (while repressing others). The levels of repression and support and the nature of the groups that give their support (labor, business, ethnic group, etc.) determine the character of the dictatorship. Among other results discussed, I show that some types of dictators – tinpots and timocrats – respond to an improvement in economic performance by lowering repression, while others – totalitarians and tyrants – respond by raising it. Finally I discuss optimal policy by the democracies toward dictatorships and I show that a single standard-aid or trade with a progressively tightening human rights constraint- is desirable if aid or trade with dictatorships of any type is to lower, not raise, repression. -

Dictatorship and Revolution: Socio-Political Reconstructions of Collective Memory in Post-Authoritarian Portugal ; Dictadura

Culture & History Digital Journal 3(2) December 2014, e017 eISSN 2253-797X doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2014.017 Dictatorship and revolution: Socio-political reconstructions of collective memory in post-authoritarian Portugal1 Manuel Loff Universidade do Porto and Instituto de História Contemporânea (Universidade Nova de Lisboa), Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Via Panorâmica, s/n, 4150-564 Porto PORTUGAL e-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 15 September 2014. Accepted: 31 October 2014. ABSTRACT: This article inserts itself into larger discussions regarding post-dictatorship memory politics in Portu- gal and comparative studies of similar histories of violence in Europe, particularly examinations of National-Social- ism, Nazism and the Holocaust, as well as comparative studies of twentieth-century fascist dictatorships in the Ibe- rian peninsula. In spite of the revolutionary, radical nature of the Portuguese democratisation process, studies conducted during the last four decades on the social and political (re)constructions of memory regarding the Portu- guese dictatorship (1926-1974) have demonstrated that state policies regarding the past have depicted the dictator- ship as one that is very similar to events in countries where the process of democratic transition was actually quite different from that of Portugal. Right-wing groups and those who self-describe as “victims” of processes of decolo- nisation that occurred between 1974 and 1975 have established a pattern of public debate that leaves no room for discussing the dictatorship without also referring to the 1974-1975 Revolution. This mode of debate seems to sug- gest that these two periods of history are indicative of a global regime phenomenon and that both the processes of decolonisation and revolution affected Portuguese society in similar ways. -

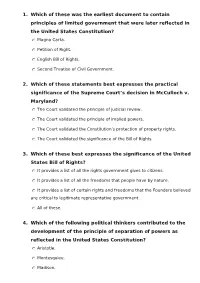

Bill of Rights Institute

1. Which of these was the earliest document to contain principles of limited government that were later reflected in the United States Constitution? Magna Carta. Petition of Right. English Bill of Rights. Second Treatise of Civil Government. 2. Which of these statements best expresses the practical significance of the Supreme Court’s decision in McCulloch v. Maryland? The Court validated the principle of judicial review. The Court validated the principle of implied powers. The Court validated the Constitution’s protection of property rights. The Court validated the significance of the Bill of Rights. 3. Which of these best expresses the significance of the United States Bill of Rights? It provides a list of all the rights government gives to citizens. It provides a list of all the freedoms that people have by nature. It provides a list of certain rights and freedoms that the Founders believed are critical to legitimate representative government . All of these. 4. Which of the following political thinkers contributed to the development of the principle of separation of powers as reflected in the United States Constitution? Aristotle. Montesquieu. Madison. All of these. 5. Which statement best reflects James Madison’s argument about separation of powers? The powers delegated to the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government should be completely separated from one another. Powers should be shared between branches so that each branch serves as a watchdog over the others. Ambition, as a harmful feature of human nature, must be eliminated in order to protect liberty through separation of powers. Separation of powers provided the only remedy for a dangerous accumulation of power in the hands of an elective body. -

Impact of Governance Structure on Economic and Social Performance: a Case Study of Latin American Countries

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Wharton Research Scholars Wharton Undergraduate Research May 2008 Impact of Governance Structure on Economic and Social Performance: A Case Study of Latin American Countries Joyce Meng University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars Meng, Joyce, "Impact of Governance Structure on Economic and Social Performance: A Case Study of Latin American Countries" (2008). Wharton Research Scholars. 50. https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars/50 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars/50 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Impact of Governance Structure on Economic and Social Performance: A Case Study of Latin American Countries Abstract Defined as "the division of public authority between two or more constitutionally defined orders of government – and a set of ideas which underpin such institutions", federalism emphasizes issues such as shared and divided sovereignty, multiple loyalties and identities, and governance through multi‐level institutions. Proponents of federalism have linked federalism with improved economic and social benefits, including increased political participation and personal liberties, efficient public and private markets, and a check on governmental power. Nevertheless, few studies have attempted to empirically prove these claims. In "Federalism's Values and Value of Federalism", Robert Inman created a multiple -

Democracy in the Arab World Explaining the Deficit

Democracy in the Arab World Explaining the defi cit Despite notable socio-economic development in the Arab region, a deficit in democracy and political rights has continued to prevail. This book examines the major reasons underlying the persistence of this democracy deficit over the past decades and touches on the prospect for deepening the process of democratization in the Arab world. Contributions from major scholars of the region give a cross-country analysis of economic development, political institutions and social factors, and the impact of oil wealth and regional wars, and present a model for democracy in the Arab world. Case studies are drawn from Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Sudan and the Gulf region; they build on these cross-country analyses and look beyond the influence of oil and conflicts as the major reason behind this demo- cracy deficit. The chapters illustrate how specific socio-political history of the country concerned, fear of fundamentalist groups, collusion with foreign powers and foreign interventions, and the co-option of the elites by the state also contribute to these problems of democratization facing the region. Situating the democratic position of the Arab world in a global context, this book is an important contribution to the field of Middle Eastern politics, develop- ment studies and studies on conflict and democracy. Ibrahim Elbadawi, formerly Lead Economist at the Development Research Group of the World Bank, he is currently Director of the Macroeconomics Research and Forecasting Department at the Dubai Economic Council and has published widely on macroeconomic and development policy and the economics of civil war. -

Economic and Social Rights in Authoritarian Regimes: Rights, Well-Being and Strategies of Authoritarian Rule in Singapore, Jordan and Belarus

Economic and Social Rights in Authoritarian Regimes: Rights, Well-being and Strategies of Authoritarian Rule in Singapore, Jordan and Belarus Ance Kalēja Dissertation for the academic title “Doctor rerum politicarum” In the faculty of Economic and Social Sciences, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Institute for Political Science First supervisor: Prof. Dr. Michael Haus Second supervisor: Prof. Dr. Aurel Croissant Heidelberg, 2017 Acknowledgments For the privilege of being able to conduct this work, I owe my utmost gratitude to many who have contributed to its realisation in more ways than I can express and possibly even comprehend. First, I extend my sincerest thank you to Professor Michael Haus, who supported me from the very first day, placing in me his trust, offering invaluable advice and continuously challenging my thinking through thought-provoking questions. I have come to believe that his work and approach to his students exemplifies how academia should be and I cherish the honour of having worked under his supervision. While pursuing a doctorate may, at times, be a lonely endeavour, I had the joy of undertaking this experience as part of a Promotionskolleg together with five fascinating individuals. We shared not only an office, but also our individual success, occasional defeats, mesmerising discussions and life itself. It has been my fortune to get to know them, but I owe my deepest thank you to Sophie, whose intelligence, sharp mind, strong opinions and healthy doses of much needed sarcasm resulted in a genuine friendship, which I will always hold dear. My gratitude to my parents Valda and Jevgenijs exceeds all bounds as their love and encouragement has always enabled me to set out to pursue my aspirations.