2011 Pace of Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Base Umpire Field Positioning

Base Umpire Field Positioning Responsibilities: Field Diagrams with Umpires ‐‐ small diamond base paths A position ‐‐ Base umpire will: •Watch for illegal pitches •Make the safe/out call at 1st •Be responsible for fail/foul calls from the bag and beyond Position of Base Umpire when Batter is up •If the batter‐runner gets a base hit that goes through the infield the base umpire will take the batter‐runner around the bases watching the batter‐runner touch bases and A position ‐‐ with no runners on base make any calls at the bases. B position ‐‐ with only a runner on 1st base B and C position –Base umpire will: • Be responsible for any pick off plays at any of the bases C position – all other runner combinations • Illegal pitches • Make calls on the bases unless the plate umpire is covering third base on certain Note: all positions are before each pitch – situations move accordingly during each play. • Be responsible for runners touching bases during a base hit and fly balls. Plate Umpire Movement will depend on where the ball is hit. • After the ball is hit the base umpire needs to move into different positions depending Range and Working Area of Base Umpire on the play. When moving into position, remember “Inside/Outside.” If the ball is in the infield, the base umpire will generally be outside the baseline. If the ball is hit to the outfield, you should move to the infield side of the baseline. = movement of position • Batted balls that stay in the infield, stay outside and cover 1st and 2nd base. -

Suggestions for Improving Pace of Play

SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVING PACE OF PLAY 1 SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVING PACE OF PLAY ON THE TEE Be early for your tee time. Proper pace of play begins with teeing off at the appointed time. Allow time for unloading your equipment, putting on your golf shoes, any desired practice or warm-up, purchasing any refreshments and driving your cart to the first tee. Play the right course for your ability level: Choose a set of tees with a rating of your handicap index. Or just tee it forward (Apply Legends Rule.) Establish a position on the course. If your round begins on a par 4, wait until the group ahead of you has gotten to the green before teeing off. If your round begins on a par 5, wait until the group ahead of you has hit their second shot and moved toward the green. On subsequent holes when waiting on the tee for the group in front to clear the fairway, don't be so strict about order of play. Let the short hitter - who can't reach the group ahead anyway - go ahead and hit. PLAY READY GOLF— Pick your line of play once and trust yourself. Hit when ready and safe regardless of who has the honors. Try to take no more than one practice swing, then set up to the ball and play your shot. Be ready to hit when it is your turn. Take 30 seconds, maximum, to hit your shot. Pay attention to your partners' drives. If they lose sight of the ball, you can help direct them to it and avoid any searching. -

The Jurisprudence of the Infield Fly Rule

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship Summer 2004 Taking Pop-Ups Seriously: The urJ isprudence of the Infield lF y Rule Neil B. Cohen Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] S. W. Waller Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Common Law Commons, Other Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation 82 Wash. U. L. Q. 453 (2004) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. TAKING POP-UPS SERIOUSLY: THE JURISPRUDENCE OF THE INFIELD FLY RULE NEIL B. COHEN* SPENCER WEBER WALLER** In 1975, the University of Pennsylvania published a remarkable item. Rather than being deemed an article, note, or comment, it was classified as an "Aside." The item was of course, The Common Law Origins of the Infield Fly Rule.' This piece of legal scholarship was remarkable in numerous ways. First, it was published anonymously and the author's identity was not known publicly for decades. 2 Second, it was genuinely funny, perhaps one of the funniest pieces of true scholarship in a field dominated mostly by turgid prose and ineffective attempts at humor by way of cutesy titles or bad puns. Third, it was short and to the point' in a field in which a reader new to law reviews would assume that authors are paid by the word or footnote. Fourth, the article was learned and actually about something-how baseball's infield fly rule4 is consistent with, and an example of, the common law processes of rule creation and legal reasoning in the Anglo-American tradition. -

2021 Safety Plan “Play Safe”

2021 Safety Plan “Play Safe” Board of Directors Position Name Phone # Email Chairman Kevin Zynn 717.475.6503 [email protected] Co-Chairman Adam Brown 484-678-2218 [email protected] Treasurer Joe Flaim 717.768.7989 [email protected] Secretary Heather Zynn 717.821.0227 Safety Officer Jessica Good 717-951-3231 Board Members Name Phone # Email Steve Temple 717.687.3705 [email protected] Dean Coates Table of Content Pequea Valley Youth Baseball Safety Program .................................................3 Manager’s Responsibility ..................................................................................4 Safe Behavior .....................................................................................................5 Safe Equipment ..................................................................................................5 Field Maintenance ..............................................................................................6 Unsafe Conditions ..............................................................................................6 Heat Illness.........................................................................................................8 Injuries ...............................................................................................................8 Accident Reporting Procedures .........................................................................9 Injury Report ....................................................................................................10 -

Lock Out/Tag

WHAT’S INSIDE LOCK OUT/TAG OUT Energy Isolation Most industrial accidents are caused by the unexpected energization or start-up of machines or equipment or by the uncontrolled release of energy. Many of these accidents can be prevented by proper LOCKOUT/TAGOUT procedures. OSHA standards 29 CFR 1910.147 & 1910.269 are designed to prevent deaths and serious injuries to maintenance personnel by controlling unauthorized or accidental use of energy. To perform work on industrial equipment safely, you must know how to apply energy isolation. LOTO Application and Uses STEPS TO SAFELY PERFORM MACHINE MAINTENANCE: • A disconnect switch, circuit breaker, valve or other energy isolation mechanism is put in the safe or off position. • A device is often placed over the energy- isolating mechanism to hold it in the safe position. • A lock is attached so that the equipment can’t be energized. In a TAGOUT, the energy- isolating device is placed in the safe position and a written warning is attached to it. APPLY LOTO FOR SAFE SITUATIONS: • When you must remove or bypass a guard or other safety device. • When you must place any part of your body where you could be caught by moving machinery. • When repairing electrical circuits. • When cleaning or oiling machinery with moving parts. • When clearing jammed mechanisms. REMEMBER! Locks and Tags by themselves do not de-energize equipment. Attach them only after the machinery has been isolated from its energy sources. 110 | www.honeywellsafety.com/ca | Lock Out/Tag Out ELECTRICAL LOCKOUTS North C-SAFE – Pole -

Here Comes the Strikeout

LEVEL 2.0 7573 HERE COMES THE STRIKEOUT BY LEONARD KESSLER In the spring the birds sing. The grass is green. Boys and girls run to play BASEBALL. Bobby plays baseball too. He can run the bases fast. He can slide. He can catch the ball. But he cannot hit the ball. He has never hit the ball. “Twenty times at bat and twenty strikeouts,” said Bobby. “I am in a bad slump.” “Next time try my good-luck bat,” said Willie. “Thank you,” said Bobby. “I hope it will help me get a hit.” “Boo, Bobby,” yelled the other team. “Easy out. Easy out. Here comes the strikeout.” “He can’t hit.” “Give him the fast ball.” Bobby stood at home plate and waited. The first pitch was a fast ball. “Strike one.” The next pitch was slow. Bobby swung hard, but he missed. “Strike two.” “Boo!” Strike him out!” “I will hit it this time,” said Bobby. He stepped out of the batter’s box. He tapped the lucky bat on the ground. He stepped back into the batter’s box. He waited for the pitch. It was fast ball right over the plate. Bobby swung. “STRIKE TRHEE! You are OUT!” The game was over. Bobby’s team had lost the game. “I did it again,” said Bobby. “Twenty –one time at bat. Twenty-one strikeouts. Take back your lucky bat, Willie. It was not lucky for me.” It was not a good day for Bobby. He had missed two fly balls. One dropped out of his glove. -

Supplemental Rules (Supercedes MLB Rules), and the Municipal Sports Section Participant’S Code of Conduct

CITY OF LOS ANGELES DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS MUNICIPAL SPORTS BASEBALL SUPPLEMENTAL RULES VALLEY MUNICIPAL SPORTS OFFICE 6911 Laurelgrove Ave. North Hollywood, CA 91605 (818) 765-0284 (818) 764-5794 fax e-mail: [email protected] Game Status e-mail: [email protected] (Revised September 2021) I. RESPONSIBILITIES OF ALL TEAM MANAGERS 1. The manager is personally responsible for all of the players on his roster. The managers must set a good example for his players and fans. The manager must be able to control all players on his roster, (an uncontrollable player(s) on a team may cause an entire team to lose its forfeit bond or be suspended from the league). It is the responsibility of the manager and the players, to the best of their ability, to show respect for the umpires and for the umpires’ judgment. Under no circumstances will verbal or physical abuse of the umpires be tolerated. The manager must make a concerted effort to gain cooperation from the fans. If a manager fails to control his fans, he faces the possibility of losing a game by forfeit. ALCOHOL: Any team or participant reported with alcoholic beverages before, during or after a game on Los Angeles City, Department of Recreation & Parks facilities (including the parking lots), or any game site, will be subject to automatic forfeiture of their bond. The second time this occurs the team will be suspended from further participation. 2. The manager must attend all required meetings or send a representative. An up-to-date address and telephone number of the manager and the assistant manager must be on file in the Municipal Sports Office. -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

How to Score Manual

A BASIC HOW TO SCORE BASEBALL MANUAL x 20L8 CENTRE FIELD B LEFT FIELD RIGHT FIELD 7 I SHORT STOP 2*o BASE 3*'BASE r.t' BASE 5 3 CATCHER 2 2. Legend for Scoring - Symbols and Colours NOTE: Replace # with the field position number of the fielder(s) who actually made the play(s). Replace * with the batter number. RECCIMMEND: All line-ups, game details and runs scored be written in black or blue pen. BOB # Batting out of Box I $ase on Balls BOO # Batting out of Order Balk CS # - # Caught Stealing a Base Change of Pitcher (with highlighter) PO # - # Picked off a Base ili' Hit by Pitched Ball F # Caught Fly Ball Foul tip 3'd strike caught by catcher FF # Caught Foul Fly Ball Batter swings on 3'd strike FC # Fielders Choice :, Batter watches 3'd strike HBB # Hit by Batted Ball Wild Pitch lF # lnfield Fly ,'.' ' Batter swings on 3'd strike, safe at 1" on WP L # Caught Line Drive Sacrifice (with F# or for Sac Flies) FL # Caught Foul Line Drive Sacrifice (with #-#B or I for Sac Bunts) MB # Missed Base PPR # Passing a Preceding Runner UA # Unassisted Put Out Earned Runs Colour circle # - # Assisted Put Out One base hit (single) ROL # Running Off Line Two base hit (double) INT # Offensive lnterference Three base hit (triple) Sb * Stolen Base Home run hit BALLS AND STRIKES: . Balls End of lnning drawn under last batter of inning C Called strikes Double Plays & through the 1" and 2nd out squares S Swinging strikes Triple Plays & through 1", 2no and 3'd out squares F Fouled off Outs Record or in circle MIXED COLOURS: Error - decisive, UPPER CASE ,' 3'd strike passed by catcher, safe on L't Error - extra base, lower case , l'd strike errored by catcher, safe on 1" Passed Ball :2- 3'd strike dropped by catcher, recovered but Defensive (Catcher) lnterference misfielded at 1't by first baseman Muffed Fly 2-3 3'd strike dropped by catcher, recovered Muffed Foul Fly by catcher and thrown out at 1" base Obstruction l'. -

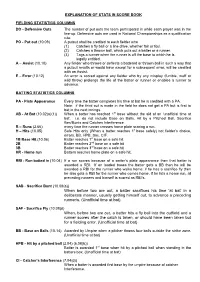

How to Do Stats

EXPLANATION OF STATS IN SCORE BOOK FIELDING STATISTICS COLUMNS DO - Defensive Outs The number of put outs the team participated in while each player was in the line-up. Defensive outs are used in National Championships as a qualification rule. PO - Put out (10.09) A putout shall be credited to each fielder who (1) Catches a fly ball or a line drive, whether fair or foul. (2) Catches a thrown ball, which puts out a batter or a runner. (3) Tags a runner when the runner is off the base to which he is legally entitled. A – Assist (10.10) Any fielder who throws or deflects a battered or thrown ball in such a way that a putout results or would have except for a subsequent error, will be credited with an Assist. E – Error (10.12) An error is scored against any fielder who by any misplay (fumble, muff or wild throw) prolongs the life of the batter or runner or enables a runner to advance. BATTING STATISTICS COLUMNS PA - Plate Appearance Every time the batter completes his time at bat he is credited with a PA. Note: if the third out is made in the field he does not get a PA but is first to bat in the next innings. AB - At Bat (10.02(a)(1)) When a batter has reached 1st base without the aid of an ‘unofficial time at bat’. i.e. do not include Base on Balls, Hit by a Pitched Ball, Sacrifice flies/Bunts and Catches Interference. R – Runs (2.66) every time the runner crosses home plate scoring a run. -

S1) Do Not Pitch (S2) Foul Ball, Time Out, Dead Ball (S3

Approved OHSAA Baseball Signal Chart Play (S1) Description: Pointing with right hand toward the pitcher and say “Play.” Ball is now live. Do Not Pitch (S2) Description: Hold right hand in front of our body with palm facing out. Ball is dead and must be put back in play (S13). Foul ball, Time Out, Dead Ball (S3) Description: Both hands open above the head. Ball is dead immediately. 1 Strike (S4) Description: Stand straight up, bring your right hand up in front of your body, make a fist and say “strike” Foul Tip (S5) Description: Stand upright and pass right hand over the left hand signifying foul tip. Ball is still live. Count (S6) Description: Left hand is balls, right hand strikes. Hold both hand up in front of your body slightly above the shoulders. Signal should be forward towards pitcher and verbalized loud enough for Catcher, Batter & Pitcher. 2 Safe/Uncaught 3rd Strike (S7) Description: Start with your arms extended directly in front of your body and swing them open at shoulder height. Appeal on Check Swing ( 8 ) Description: Step out from behind the catcher, extend your left arm, palm up and ask the base umpire “Did He Go?” Safe /Did Not Go(S9) Description: Start with your arms extended directly in front of your body and swing them open at shoulder height. Used to signal that batter did not go when plate umpire asks “Did he go”. 3 Out (S10) Description: Bring your right arm up, make a 90 degree angle, make a fist and with hammering action call, “He’s out” Infield Fly (S11) Description: Once the ball has reached its Apex and you determine it is an infield fly, point your right hand toward ball and say “Infield Fly, batter is out”. -

Beanballs and Baseball: Private Remedies Vs. Criminal Sanctions for Violence in Baseball

Volume 115 Issue 3 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 115, 2010-2011 1-1-2011 Beanballs and Baseball: Private Remedies vs. Criminal Sanctions for Violence in Baseball Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Beanballs and Baseball: Private Remedies vs. Criminal Sanctions for Violence in Baseball, 115 DICK. L. REV. (2011). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol115/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Distracted Driving: How Technological Advancements Impede Highway Safety Amy L. Brueckner* 1. INTRODUCTION Traffic safety has long been a concern of the United States' legal system.' In 1966, the passage of the Highway Safety Act and the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act empowered the federal government with the authority to "set and regulate motor vehicle and highway standards."2 Subsequent improvements in automotive design resulted in a decline of vehicle-related deaths.3 Despite these promising consequences, not all safety requirements were readily embraced.4 One of the most controversial requirements involved safety restraint systems, namely seatbelts.' Although vehicles came equipped with seatbelts, drivers and passengers retained the discretion to buckle up or not.6 Misconceptions about the benefits of seatbelts thwarted the federal government's efforts to encourage seatbelt use.7 Eventually, the National Highway Traffic Safety Association proposed that automotive manufacturers equip every vehicle with "an automatic restraint system." State legislatures followed suit and began enacting mandatory seatbelt- * J.D.