The Growing Importance of Steel Scrap in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

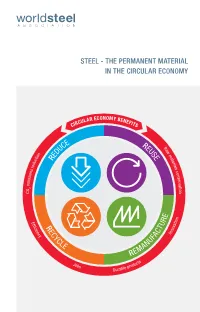

Reduce Reuse Recycle Remanufacture

STEEL - THE PERMANENT MATERIAL IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY AR ECONOMY BEN CUL EFI CIR TS E R R C E a U U w n D S m io E E a t t c R e u r i d a e l r s s c n o o n i s s s e i r v m a e t i 2 o O n C E n o E R i f t f U a ic R v o ie T n E n c C In y C Y FA C U LE N MA RE ts Jo duc bs pro Durable 1 CONTENTS Steel in the circular economy 3 Steel is essential to our modern world 5 Reduce 7 Decreasing the amount of material, energy and other resources used to create steel and reducing the weight of steel used in products. Use and reuse 11 Reuse is using an object or material again, either for its original purpose or for a similar purpose, without significantly altering the physical form of the object or material. Remanufacture 15 The process of restoring durable used steel products to as-new condition. Recycle 19 Melting steel products at the end of their useful life to create new steels. Recycling alters the physical form of the steel object so that a new application can be created from the recycled material. End notes 22 2 STEEL IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY A sustainable circular economy is one in which steel is fundamental to the circular economy. society reduces the burden on nature by ensuring The industry is continuing to expand its offer resources remain in use for as long as possible. -

Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel

ACADEMIC PULSE Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel teelmakers have traditionally viewed Research Continues to Improve the electric arc furnaces (EAFs) as unsuitable Quality of Steel for producing steel with the highest- Even with continued improvements to the Squality surface finish because the process design of steelmaking processes, the steelmaking uses recycled steel instead of fresh iron. With over research community has focused their attention 100 years of processing improvements, however, on the fundamental materials used in steelmaking EAFs have become an efficient and reliable in order to improve the quality of steel. In my lab steelmaking alternative to integrated steelmaking. In at Carnegie Mellon University, we have several fact, steel produced in a modern-day EAF is often research projects that deal with controlling the DR. P. BILLCHRIS MAYER PISTORIUS indistinguishable from what is produced with the impurity concentration and chemical quality of POSCOManaging Professor Editorof Materials integrated blast-furnace/oxygen-steelmaking route. steel produced in EAFs. Science412-306-4350 and Engineering [email protected] Mellon University Improvements in design, coupled with research For example, we recently used mathematical developments in metallurgy, mean high-quality steel modeling to explore ways to control produced quickly and energy-efficiently. phosphorus. Careful regulation of temperature, slag and stirring are needed to produce low- Not Your (Great-) Grandparent’s EAF phosphorus steel. We analyzed data from Especially since the mid-1990s, there have been operating furnaces and found that, in many significant improvements in the design of EAFs, cases, the phosphorus removal reaction could which allow for better-functioning burners and a proceed further. -

STEEL in the CIRCULAR ECONOMY a Life Cycle Perspective CONTENTS

STEEL IN THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY A life cycle perspective CONTENTS Foreword 3 The circular economy 4 Life cycle thinking 6 The life cycle assessment (LCA) approach 8 worldsteel’s LCA methodology and life cycle inventory (LCI) database 10 Sustainability and life cycle assessment 12 LCA in the steel industry 14 LCA by life cycle phase 15 Raw materials and steel production 15 Markets for by-products 16 Manufacturing and use 16 Reuse and remanufacturing 18 Recycling 19 LCA initiatives 20 Regional and global initiatives 21 Market sector initiatives 22 Construction 22 Automotive 24 Packaging 25 End notes 28 Glossary 29 Cover image: Steel staircase, office building, Prague, Czech Republic Design: double-id.com FOREWORD We live in a rapidly changing world with finite resources. Too many legislative bodies around the world At the same time, improvements in standards of living still enact regulations which only affect the “use and eradication of poverty, combined with global phase” of a product’s life, for example water and population growth, exert pressure on our ecosystems. energy consumption for washing machines, energy consumption for a fridge or CO2 emissions whilst As steel is everywhere in our lives and is at the heart driving a vehicle. This focus on the “use phase” can of our sustainable future, our industry is an integral part lead to more expensive alternative lower density of the global circular economy. The circular economy materials being employed but which typically have a promotes zero waste, reduces the amount of materials higher environmental burden when the whole life cycle used, and encourages the reuse and recycling of is considered. -

The Stainless Steel Family

The Stainless Steel Family A short description of the various grades of stainless steel and how they fit into distinct metallurgical families. It has been written primarily from a European perspective and may not fully reflect the practice in other regions. Stainless steel is the term used to describe an extremely versatile family of engineering materials, which are selected primarily for their corrosion and heat resistant properties. All stainless steels contain principally iron and a minimum of 10.5% chromium. At this level, chromium reacts with oxygen and moisture in the environment to form a protective, adherent and coherent, oxide film that envelops the entire surface of the material. This oxide film (known as the passive or boundary layer) is very thin (2-3 namometres). [1nanometre = 10-9 m]. The passive layer on stainless steels exhibits a truly remarkable property: when damaged (e.g. abraded), it self-repairs as chromium in the steel reacts rapidly with oxygen and moisture in the environment to reform the oxide layer. Increasing the chromium content beyond the minimum of 10.5% confers still greater corrosion resistance. Corrosion resistance may be further improved, and a wide range of properties provided, by the addition of 8% or more nickel. The addition of molybdenum further increases corrosion resistance (in particular, resistance to pitting corrosion), while nitrogen increases mechanical strength and enhances resistance to pitting. Categories of Stainless Steels The stainless steel family tree has several branches, which may be differentiated in a variety of ways e.g. in terms of their areas of application, by the alloying elements used in their production, or, perhaps the most accurate way, by the metallurgical phases present in their microscopic structures: . -

Used Motor Oil and Filter Recycling Guide

USED MOTOR OIL & FILTER RECYCLING LEARN MORE Used Motor Oil and Oil Filter Recycling Guide Used Motor Oil is a Hazardous Waste Used motor oil is a hazardous waste that should never be put in the garbage or dumped in the storm drains or on the ground. Just one quart of motor oil can contaminate 250,000 gallons of water, creating health risks and environmental impacts across our community. Recycling is Free and Easy Used motor oil can be refined and Recycling right is more than an individual choice - it is part of how we are all reconditioned to become usable again. Paper, making a difference for a cleaner Oakland and more livable neighborhoods. steel, and plastic from used oil filters can also With your participation, Oakland’s Zero Waste program strives to divert all be recycled. recyclable and compostable material away from our landfills. There are three options for recycling used Your used motor oil recycling team is a partnership between the City of motor oil and filters: Oakland, California Waste Solutions, and CalRecycle. Our commitment to you is to provide the services and information you need to recycle right. 1. Curbside residential recycling pickup 2. Certified Collection Center drop-off locations When you pledge to recycle right, we’re here to help. 3. Household Hazardous Waste (HHW) collection facility Oaklanders Recycle No matter where you live in the City, there is a free and easy recycling option Contacts and Important Phone Numbers close to you. Visit recycleusedoil.org to find a location near you. California Waste Solutions ...............................................................(510) 625–5263 Used Motor Oil & Filters Improper Disposal is Illegal Disposal [email protected] www.calwaste.com 我們講中文 Hablamos español When you dispose hazardous materials properly, it benefits Household Hazardous Waste Drop Off ...................................... -

Steelmaking by Electric Arc Furnaces Cleaner, More Efficient

EVRAZ Canadian Steel: Low Carbon Footprint November 2016 Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs) with metal scrap: cleaner, more efficient • EVRAZ Regina utilizes two Electricity Steelmaking EAFs to make up to 1.1 Generation million tons of steel per Energy used CO2 emissions CO2 emissions year kg / ton of steel kWh / ton of steel grams / kWh -79% • Over 91% of steelmaking -64% -81% 2,081 in China is from Blast 4,624 764 Oxygen Furnaces (BOFs), which use iron ore, coking coal, and other inputs • For every one ton of steel scrap made into new steel, over 1,400kg of iron ore, 1,647 740kg of coal, and 120kg 441 147 of limestone are saved Overseas input shipping to China Blast EAF Blast EAF China Canada Furance Furnace Sources: BOF percentage: Worldsteel. Shipping emissions: National Technical University of Athens. Steelmaking: Midrex – Blast Furnace assuming 11% Scrap, EAF Use of 100% scrap. Scrap statistics: Worldsteel. Electricity Generation: IEA 2011 2 EVRAZ cleaner EAFs, Canada’s power generation outpace others Emissions from Steelmaking emissions and energy use energy generation Energy used CO2 emissions CO2 emissions kg / ton of steel kWh / ton of steel grams / kWh -79% -64% 2,081 4,624 -81% 764 1,526 3,419 2,327 476 470 929 1,647 441 147 China Germany Turkey EVRAZ Blast GermanyTurkey EAF China Turkey Germany Canada - BOF Canada Furnace - EAF - China Overseas shipping of inputs Sources: BOF percentage: Worldsteel. Shipping emissions: National Technical University of Athens, from China to BC, Europe to Houston. Steelmaking: Midrex – Blast Furnace assuming 11% Scrap, EAF Use of 100% scrap. -

AISI | Electric Arc Furnace Steelmaking

http://www.steel.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Articles3&TEMPLATE=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=12308 Home Steelworks Home Electric Arc Furnace Steelmaking By Jeremy A. T. Jones, Nupro Corporation SIGN UP to receive AISI's FREE e-news! Read the latest. Email: Name: Join Courtesy of Mannesmann Demag Corp. FURNACE OPERATIONS The electric arc furnace operates as a batch melting process producing batches of molten steel known "heats". The electric arc furnace operating cycle is called the tap-to-tap cycle and is made up of the following operations: Furnace charging Melting Refining De-slagging Tapping Furnace turn-around Modern operations aim for a tap-to-tap time of less than 60 minutes. Some twin shell furnace operations are achieving tap-to-tap times of 35 to 40 minutes. 10/3/2008 9:36 AM http://www.steel.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Articles3&TEMPLATE=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=12308 Furnace Charging The first step in the production of any heat is to select the grade of steel to be made. Usually a schedule is developed prior to each production shift. Thus the melter will know in advance the schedule for his shift. The scrap yard operator will prepare buckets of scrap according to the needs of the melter. Preparation of the charge bucket is an important operation, not only to ensure proper melt-in chemistry but also to ensure good melting conditions. The scrap must be layered in the bucket according to size and density to promote the rapid formation of a liquid pool of steel in the hearth while providing protection for the sidewalls and roof from electric arc radiation. -

The Energy Benefit of Stainless Steel Recycling

ARTICLE IN PRESS Energy Policy ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]] www.elsevier.com/locate/enpol The energy benefit of stainless steel recycling Jeremiah Johnsona,b,Ã, B.K. Reckb, T. Wangb, T.E. Graedelb aProgram in Environmental Engineering, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA bCenter for Industrial Ecology, School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, 205 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT 02140, USA Received 5 December 2006; accepted 21 August 2007 Abstract The energy used to produce austenitic stainless steel was quantified throughout its entire life cycle for three scenarios: (1) current global operations, (2) 100% recycling, and (3) use of only virgin materials. Data are representative of global average operations in the early 2000s. The primary energy requirements to produce 1 metric ton of austenitic stainless steel (with assumed metals concentrations of 18% Cr, 8% Ni, and 74% Fe) is (1) 53 GJ, (2) 26 GJ, and (3) 79 GJ for each scenario, with CO2 releases totaling (1) 3.6 metric tons CO2, (2) 1.6 metric tons CO2, and (3) 5.3 metric tons CO2. Thus, the production of 17 million metric tons of austenitic stainless steel in 2004 used 17 approximately 9.0 Â 10 J of primary energy and released 61 million metric tons of CO2. Current recycling operations reduce energy use 17 by 33% (4.4 Â 10 J) and CO2 emissions by 32% (29 million tons). If austenitic stainless steel were to be produced solely from scrap, which is currently not possible on a global level due to limited availability, energy use would be 67% less than virgin-based production and CO2 emissions would be cut by 70%. -

Euric Metal Recycling Factsheet

Metal Recycling Factsheet EuRIC AISBL – Recycling: Bridging Circular Economy & Climate Policy 2 EuRIC Metal Recycling Factsheet METAL RECYCLING INDUSTRY Metals are broadly present in a variety of goods with both short and long term use (i.e., steel bars in our houses, bridges, and turbines, copper cables for communication, railway tracks, kitchen equipment, cars, etc.). EU economic growth is deeply linked to the use of metals with metal supply widely depending on metal scrap. Scrap metals from recycling compete globally on commodity markets, hence the need to ensure both a well- functioning internal market for metal recyclers and unhampered access to international markets. Createdfrom the by Noun Bagundas Project CO2 EuRIC AISBL – Recycling: Bridging Circular Economy & Climate Policy 3 EuRIC Metal Recycling Factsheet Metals & Circular Economy Results of the growing metal demand on a linear economy are: • Declining ore grades. • Resource scarcity and price hikes. DISTRIB UTI • Environmental impacts (air and water pollution, land degradation, N ON IO biodiversity loss). CT U D O R P Despite historical metal reuse, there is an increasing need to move C O N towards a more efficient circular economy model. S U M P Thanks to their unique properties, metals can be indefinitely T CIRCULAR ECONOMY I O recycled. At their end-of-life (EoL) stage, products made of metals N can be re-processed via mechanical treatment and re-introduced to R O T the production process to make new metals. As a result, value chains C E S R are already largely circular, despite room for improvement. E G - U N I S L E C / R Y E C P E A R Metal recycling closes the loop within the production process, I R / R E C Y C E L therefore reducing the amount of waste that goes into landfill and the amount of primary raw materials required. -

Gardenworks Guide to Compost and Mulching

The Green Institute, 2801 21 st Ave S, Suite 110, Minneapolis, MN 55407 612-278-7123 [email protected] www.gardenworksMN.org ~ Promoting and Preserving Community Gardening acro ss the Twin Cities ~ Composting and Mulching Created by Corrie Zoll, GreenSpace Partners, The Green Institute, for a Compost Workshop, February 2003. Updated by GardenWorks, April 2007. Making Compost Why should I make compost? Whether or not you’re a gardener, composting is a common sense way to handle a significant amount of the waste you produce. Think of it like recycling cans. You buy a can of Spam, use the Spam, and you’re left with the can. The can is made of steel. That steel can be used again. That steel is much easier to reuse if you recycle it than if you put it in a landfill. Your coffee grounds, vegetable peels, moldy bread, grass clippings, and fall leaves are also made from reusable materials. Like steel, these materials are much easier to reuse if you recycle them than if you put them in a landfill. But unlike recycling steel, you can recycle coffee grounds at home, and you can use the final product at home, too. I think composting today is where steel recycling was 25 years ago. People know about it, people know it’s a good thing to do, but there isn’t much incentive to do it. As the amount of waste we produce increases, so does the cost per volume of disposing of that waste material. Cities can’t avoid looking for new ways to keep waste out of landfills. -

Framework for Designing Sustainable Structures Through Steel Beam Reuse

sustainability Article Framework for Designing Sustainable Structures through Steel Beam Reuse Seongjun Kim 1 and Sung-Ah Kim 2,* 1 Department of Convergence Engineering for Future City, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Architecture, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 16419, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2020; Accepted: 12 November 2020; Published: 15 November 2020 Abstract: The architecture, engineering, and construction sector requires carbon-intensive materials, such as steel, in the construction process and generates a large amount of waste in the life cycle. This causes global warming and waste problems. The demand for the reuse of construction materials is increasing, although it is not the convention, to reduce the environmental impact. Although the sustainable effect of the reuse of materials has been proven in several studies, materials are not always reused in practice, owing to the lack of an information system for reusable materials and the economic uncertainty. In this study, we propose a framework for designing structures using reusable steel beams. The design framework consists of a material bank and a design support tool. The material bank provides information on reusable materials based on the building information modeling. The design support tool generates efficient material procurement plans and provides information about the environmental and economic impact of the project. In a case study used to verify the framework, CO2 emissions were reduced by up to 77% through material reuse, which was consistent with the results of previous studies. However, owing to the cost of processing reusable materials, the overall cost was found to increase by up to about 40%. -

Used Oil Oil Filters

Where can I recycle my used Oil or Oil Filters? Tips from Kaya Locations across the state accept used motor oil and oil filters for recycling. Automotive Used oil is recycled by being re-refined related businesses statewide may serve as to remove contaminants and water. a drop off locations for your used oil or oil Oil displaying the API “Donut” or filters or take them to your local Regional ILSAC “Starburst” meets the same Change Our Ways. Collection Center (RCC). certification as virgin motor oil and can be used in engines or as lubricating oil. For the location of your nearest RCC, visit Change Our World. www.SafeSmartSolutions.org. For the location of some businesses that accept used oil or oil filters visit the Automotive Products Disposal Directory at www.iowadnr.gov/FABA For more information contact your local Solid Waste Agency USED OIL or your Regional Collection Center. API “Donut” ILSAC “Starburst” www.SafeSmartSolutions.org AND OIL FILTERS What happens to used motor oil I bring in to recycle? Used oil can be reprocessed into fuel that can be used in furnaces for heat, or in power plants to generate electricity for homes, schools and businesses. It can also be used in industrial and utility boilers or blended for marine fuels. Used motor oil can also be re-refined into lubricating oils that meet the same API specifications as virgin motor oil. Used Oil Used Oil Filters Oil doesn’t wear out, it just gets dirty. As it Even after a filter has been drained for lubricates your engine it picks up a variety several hours according to federal guidelines, of contaminants, causing the need for an oil several ounces of oil may remain trapped change.