The Arctic Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chamber Meeting Day

Yukon Legislative Assembly Number 180 1st Session 33rd Legislature HANSARD Wednesday, December 3, 2014 — 1:00 p.m. Speaker: The Honourable David Laxton YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY SPEAKER — Hon. David Laxton, MLA, Porter Creek Centre DEPUTY SPEAKER — Patti McLeod, MLA, Watson Lake CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Darrell Pasloski Mountainview Premier Minister responsible for Finance; Executive Council Office Hon. Elaine Taylor Whitehorse West Deputy Premier Minister responsible for Education; Women’s Directorate; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Brad Cathers Lake Laberge Minister responsible for Community Services; Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation; Yukon Lottery Commission Government House Leader Hon. Doug Graham Porter Creek North Minister responsible for Health and Social Services; Yukon Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Scott Kent Riverdale North Minister responsible for Energy, Mines and Resources; Yukon Energy Corporation; Yukon Development Corporation Hon. Currie Dixon Copperbelt North Minister responsible for Economic Development; Environment; Public Service Commission Hon. Wade Istchenko Kluane Minister responsible for Highways and Public Works Hon. Mike Nixon Porter Creek South Minister responsible for Justice; Tourism and Culture GOVERNMENT PRIVATE MEMBERS Yukon Party Darius Elias Vuntut Gwitchin Stacey Hassard Pelly-Nisutlin Hon. David Laxton Porter Creek Centre Patti McLeod Watson Lake OPPOSITION MEMBERS New Democratic Party Elizabeth Hanson Leader of the Official -

Journals of the Yukon Legislative Assembly 2021 Special Sitting

JOURNALS YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY First Session 35th Legislature 2021 Special Sitting May 11, 2021 – May 31, 2021 Speaker: The Hon. Jeremy Harper YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY First Session, 35th Legislative Assembly 2021 Special Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Jeremy Harper, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Annie Blake, MLA, Vuntut Gwitchin DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Emily Tredger, MLA, Whitehorse Centre CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Deputy Premier Government House Leader Minister of Health and Social Services; Justice Hon. Nils Clarke Riverdale North Minister of Highways and Public Works; Environment Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne- Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Public Service Southern Lakes Commission; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek Minister of Economic Development; Tourism and Culture; South Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Jeanie McLean Mountainview Minister of Education; Minister responsible for the Women’s Directorate OFFICIAL OPPOSITION Yukon Party Currie Dixon Leader of the Official Opposition -

2021 Special Sitting Index

Yukon Legislative Assembly 1st Session 35th Legislature Index to HANSARD May 11, 2021 to May 31, 2021 SPECIAL SITTING YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2021 Special Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Jeremy Harper, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Annie Blake, MLA, Vuntut Gwitchin DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Emily Tredger, MLA, Whitehorse Centre CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Deputy Premier Government House Leader Minister of Health and Social Services; Justice Hon. Nils Clarke Riverdale North Minister of Highways and Public Works; Environment Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne-Southern Lakes Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Public Service Commission; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek South Minister of Economic Development; Tourism and Culture; Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Jeanie McLean Mountainview Minister of Education; Minister responsible for the Women’s Directorate OFFICIAL OPPOSITION Yukon Party Currie Dixon Leader of the Official Opposition Scott Kent Official Opposition House Leader Copperbelt North Copperbelt -

The River's out - Summer's on the Way!

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 • VOL. 25, NO. 1 $1.25 KLONDIKE Happy Breakup! SUN The River's out - summer's on the way! The visiting fiddlers from Selkirk Street Elementary School chill out at Klondyke Cream & Candy, shepherded by former RSS teacher and Palace Grand performer, Grant Hartwick. Photo by Dan Davidson. in this Issue Fire on 7th Ave. 3 Kokopelle farm 6 May 2 is this year's breakup day 7 It's our birthday Cigarettes lit this Yukon Housing Part of Sunnydale returns to its Next comes the ferry launch. Max’s New month! It's been 25 unit. farming roots. Summer Hours years of Sun shine. What to see and do in Dawson! 2 New taco cart 8 Gertie's story 12 What's Your Story 22 Uffish Thoughts 4 Family Time 9 TV Guide 14-18 Business Directory & Job Board 23 Letters 5 SOVA grads 10 Stacked 20 City notices 24 P2 WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: hatha yoga With jOanne van nOstranD: This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many Tuesdays and Thursdays, 5:30- activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and 7SOVA p.m. E-mail [email protected] 24 hours in advance. planning, so let us know in good time! To join this listing contact the office at [email protected]. aDMin Office hOurs DAWSON CITY INTERNATIONAL GOLD SHOW: liBrarY hOurs : Monday to Thursday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. -

Yukon Premier Announces Changes to Cabinet| Government of Yukon News Release

8/21/2017 Yukon Premier announces changes to Cabinet| Government of Yukon news release FOR RELEASE January 16, 20 15 Yukon Premier announces changes to Cabinet “The Cabinet ministers announced today bring a great deal of depth and experience to their new jobs, and will serve Yukoners with continued energy and commitment.” -Premier and Minister of the Executive Council Office Darrell Pasloski WHITEHORSE—Premier Darrell Pasloski has announced a strengthened and diversified Cabinet and new roles for backbencher MLAs. The changes include one new member of Cabinet, as well as a new Government House Leader, both from rural Yukon. “I am proud of our government’s accomplishments and confident th at these changes will put us in an even stronger position to meet the challenges ahead, serve Yukoners and make our territory an even better place to live, work, play and raise a family,” said Pasloski. “Our new team is built on the strengths and expertise of each minister, while also allowing them to broaden their knowledge and experience within government. This provides for both stability and fresh perspectives.” The changes announced today take effect immediately. Premier Darrell Pasloski, Executive Council Office, Finance MLA for Mountainview Minister Elaine Taylor, MLA Deputy Premier, Tourism and Culture, for Whitehorse West Women’s Directorate, French Language Services Directorate Minister Brad Cathers, MLA Justice, Yukon Development for Lake Laberge Corporation/Yukon Energy Corporation Minister Doug Graham, MLA Education for Porter Creek North Minister -

JANUARY 13, 2016 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2016 • VOL. 26, NO. 16 $1.50 Raven says the ice bridge is safe and KLONDIKE the sun's returning. SUN Seasonal Roundup and News from the Ice Bridge Gathering to see the Baby Jesus, a photo from the Christmas Eve Pageant. Photo by Betty Davidson in this Issue Saturday Painting Club 6 May the Force be with Us 8 High Tea a Great Success 9 Magazines and Lindsey Tyne profiles the Painting Mayor Potoroka explains the new Thanks to all the folks who Club. Force Main. organized and attended our fund Books Galore! raising Tea. STORE HOURS: 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday to Saturday See and Do / Authors on 8th 2 Gordon Caley Obituary 6 Palace Grand to get upgrades 11 History Hunter: Klondike Christmases 18 Christmas Eve Pageant 3 Municipal Act amendments 8 TV Guide 12-16 Classifieds & Job Board 19 Noon to 5p.m. on Sunday Uffish Thoughts: Ice Bridge issues 4 Kim Fu's public reading 10 20 years ago 17 City Notices 20 P2 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2016 THE KLONDIKE SUN Authors on 8th What to Authors on 8th poetry entry A Tribute to the AND Poetry SEE DO (Extra)ordinary Submission in DAWSON now: Women of the North By Aileen Stalker This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and planning, so let us know in good time! To join this Meetingslisting contact the office at [email protected]. IODE DAWSON CITY: Meet first Wednesday of each month at When I walk through these mossy old gravestones Rhomeoya Lof C Joyceanadian Caley atLE 7:30GION p.m. -

Chamber Meeting Day 4

Yukon Legislative Assembly Number 4 1st Session 35th Legislature HANSARD Monday, May 17, 2021 — 1:00 p.m. SPECIAL SITTING Speaker: The Honourable Jeremy Harper YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2021 Special Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Jeremy Harper, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Annie Blake, MLA, Vuntut Gwitchin DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Emily Tredger, MLA, Whitehorse Centre CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Deputy Premier Government House Leader Minister of Health and Social Services; Justice Hon. Nils Clarke Riverdale North Minister of Highways and Public Works; Environment Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne-Southern Lakes Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Public Service Commission; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek South Minister of Economic Development; Tourism and Culture; Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Jeanie McLean Mountainview Minister of Education; Minister responsible for the Women’s Directorate OFFICIAL OPPOSITION Yukon Party Currie Dixon Leader of the Official Opposition Scott Kent Official Opposition -

Procedures and Practices of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts

Yukon Legislative Assembly Standing Committee on Public Accounts 35th Yukon Legislative Assembly Procedures and Practices of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts Committee Authority and Terms of Reference The basic purpose of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts is to ensure economy, efficiency and effectiveness in public spending. The committee’s authority is derived from Standing Order 45(3) of the Standing Orders of the Yukon Legislative Assembly, which says At the commencement of the first Session of each Legislature a Standing Committee on Public Accounts shall be appointed and the Public Accounts and all Reports of the Auditor General shall stand referred automatically and permanently to the said Committee as they become available. On May 17, 2021, the Yukon Legislative Assembly adopted the following motion: THAT Currie Dixon, Scott Kent, the Hon. Richard Mostyn, the Hon. Jeanie McLean, and Kate White be appointed to the Standing Committee on Public Accounts established pursuant to Standing Order 45(3); THAT the committee have the power to call for persons, papers, and records and to sit during intersessional periods; and THAT the Clerk of the Legislative Assembly be responsible for providing the necessary support services to the committee. (Motion No. 11) The committee first met on June 1, 2021. At that meeting, the committee elected Currie Dixon as Chair and Kate White as Vice-Chair. Accountability and Responsibility Since the first Public Accounts Committee of the Yukon Legislative Assembly was appointed on October 22, 1979, the committee has functioned in accordance with many of the observations made by the Royal Commission on Financial Management and Accountability (the Lambert Commission), which issued its final report in March 1979. -

Yukon Legislative Assembly

Yukon Legislative Assembly Number 167 1st Session 33rd Legislature HANSARD Wednesday, November 5, 2014 — 1:00 p.m. Speaker: The Honourable David Laxton YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY SPEAKER — Hon. David Laxton, MLA, Porter Creek Centre DEPUTY SPEAKER — Patti McLeod, MLA, Watson Lake CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Darrell Pasloski Mountainview Premier Minister responsible for Finance; Executive Council Office Hon. Elaine Taylor Whitehorse West Deputy Premier Minister responsible for Education; Women’s Directorate; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Brad Cathers Lake Laberge Minister responsible for Community Services; Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation; Yukon Lottery Commission Government House Leader Hon. Doug Graham Porter Creek North Minister responsible for Health and Social Services; Yukon Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Scott Kent Riverdale North Minister responsible for Energy, Mines and Resources; Yukon Energy Corporation; Yukon Development Corporation Hon. Currie Dixon Copperbelt North Minister responsible for Economic Development; Environment; Public Service Commission Hon. Wade Istchenko Kluane Minister responsible for Highways and Public Works Hon. Mike Nixon Porter Creek South Minister responsible for Justice; Tourism and Culture GOVERNMENT PRIVATE MEMBERS Yukon Party Darius Elias Vuntut Gwitchin Stacey Hassard Pelly-Nisutlin Hon. David Laxton Porter Creek Centre Patti McLeod Watson Lake OPPOSITION MEMBERS New Democratic Party Elizabeth Hanson Leader of the Official -

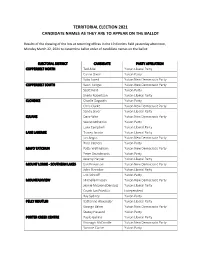

Territorial Election 2021 Candidate Names As They Are to Appear on the Ballot

TERRITORIAL ELECTION 2021 CANDIDATE NAMES AS THEY ARE TO APPEAR ON THE BALLOT Results of the drawing of the lots at returning offices in the 19 districts held yesterday afternoon, Monday March 22, 2021 to determine ballot order of candidate names on the ballot: ELECTORAL DISTRICT CANDIDATE PARTY AFFILIATION COPPERBELT NORTH Ted Adel Yukon Liberal Party Currie Dixon Yukon Party Saba Javed Yukon New Democratic Party COPPERBELT SOUTH Kaori Torigai Yukon New Democratic Party Scott Kent Yukon Party Sheila Robertson Yukon Liberal Party KLONDIKE Charlie Dagostin Yukon Party Chris Clarke Yukon New Democratic Party Sandy Silver Yukon Liberal Party KLUANE Dave Weir Yukon New Democratic Party Wade Istchenko Yukon Party Luke Campbell Yukon Liberal Party LAKE LABERGE Tracey Jacobs Yukon Liberal Party Ian Angus Yukon New Democratic Party Brad Cathers Yukon Party MAYO TATCHUN Patty Wallingham Yukon New Democratic Party Peter Grundmanis Yukon Party Jeremy Harper Yukon Liberal Party MOUNT LORNE - SOUTHERN LAKES Erik Pinkerton Yukon New Democratic Party John Streicker Yukon Liberal Party Eric Schroff Yukon Party MOUNTAINVIEW Michelle Friesen Yukon New Democratic Party Jeanie McLean (Dendys) Yukon Liberal Party Coach Jan Prieditis Independent Ray Sydney Yukon Party PELLY NISUTLIN Katherine Alexander Yukon Liberal Party George Bahm Yukon New Democratic Party Stacey Hassard Yukon Party PORTER CREEK CENTRE Paolo Gallina Yukon Liberal Party Shonagh McCrindle Yukon New Democratic Party Yvonne Clarke Yukon Party ELECTORAL DISTRICT CANDIDATE PARTY AFFILIATION -

Report of the Chief Electoral Officer

REPORT OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER OF YUKON ON POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2012 REPORT OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER OF YUKON ON POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS 2012 April 2013 Published by the Chief Electoral Officer of Yukon (date) Hon. David Laxton Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Yukon Legislative Assembly Whitehorse, Yukon Dear Mr. Laxton: I am pleased to submit a report on the annual financial returns for the registered political parties for the 2012 calendar year. This report is prepared pursuant to section 398 of the Elections Act. Sincerely, Brenda McCain-Armour Assistant Chief Electoral Officer TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Report Respecting Financial Provisions for Candidates and Political Parties …………………………………………………… 1 Appendix I: Election Financing Return 2012 Annual Return, Yukon Party............................................ 2 Appendix II: Election Financing Return 2012 Annual Return, Yukon First Nations Party ……………… 4 Appendix III: Election Financing Return 2012 Annual Return, Yukon Green Party …………………….. 5 Appendix IV: Election Financing Return 2012 Annual Return, Yukon Liberal Party ............................... 6 Appendix V: Election Financing Return 2012 Annual Return, Yukon New Democratic Party ................ 7 Appendix VI: Outstanding Election Financing Returns, 2000 and 2002 General Elections …..…………………………................... 9 REPORT RESPECTING FINANCIAL PROVISIONS FOR CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL PARTIES, 2012 The Elections Act (S.Y. 2004, c. 9) states in section 398: "(1) The chief electoral officer may report to the Legislative Assembly respecting (a) the information contained in returns filed by registered political parties or candidates, (b) anonymous contributions, or (c) any other matter under this Part. (2) The chief electoral officer may include in any report under paragraph (1)(a) the names of contributors over $250 and any debt holders." This report includes the information contained in the annual returns from the registered political parties for the calendar year 2012. -

Order Paper of the Yukon Legislative Assembly

No. 3 ORDER PAPER OF THE YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY First Session 35th Legislature Thursday, May 13, 2021 Prayers DAILY ROUTINE Introduction of Visitors Tributes Tabling Returns and Documents Presenting Reports of Committees Petitions Introduction of Bills Notices of Motions Ministerial Statement Oral Question Period ORDERS OF THE DAY GOVERNMENT DESIGNATED BUSINESS Motion for an Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne 1. Motion No. 20 Hon. Ms. McLean, Minister of Education THAT the following address be presented to the Commissioner of Yukon: MAY IT PLEASE THE COMMISSIONER: We, the Members of the Yukon Legislative Assembly, beg leave to offer our humble thanks for the gracious Speech which you have addressed to the House. Adjourned debate: Hon. Mr. Pillai (May 12, 2021) Government Motions 1. Motion No. 4 Hon. Ms. McPhee, Government House Leader THAT, notwithstanding Standing Order 75(2), the maximum number of sitting days for the 2021 Special Sitting shall be 11 sitting days; THAT, notwithstanding Standing Order 75(7), the provisions of Chapter 14 of the Standing Orders of the Yukon Legislative Assembly shall apply to the 2021 Special Sitting, in the same manner as if it were a Spring or Fall Sitting; and Order Paper - 2 - No. 3 – May 13, 2021 THAT the provisions of Standing Order 76 shall apply on the sitting day that the Assembly has reached the maximum number of sitting days allocated for the 2021 Special Sitting. 2. Motion No. 5 Hon. Ms. McPhee, Government House Leader THAT, notwithstanding any current Standing Orders regarding members’ physical presence in the Chamber, for the duration of the 2021 Special Sitting, if the Legislative Assembly stands adjourned for an indefinite period of time, the Government House Leader and at least one of the other House Leaders together may request that the Legislative Assembly meet virtually by video conference, with all the Members of the Legislative Assembly being able to participate remotely.