Mitigating Mistrust Tspace.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chamber Meeting Day

Yukon Legislative Assembly Number 180 1st Session 33rd Legislature HANSARD Wednesday, December 3, 2014 — 1:00 p.m. Speaker: The Honourable David Laxton YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY SPEAKER — Hon. David Laxton, MLA, Porter Creek Centre DEPUTY SPEAKER — Patti McLeod, MLA, Watson Lake CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Darrell Pasloski Mountainview Premier Minister responsible for Finance; Executive Council Office Hon. Elaine Taylor Whitehorse West Deputy Premier Minister responsible for Education; Women’s Directorate; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Brad Cathers Lake Laberge Minister responsible for Community Services; Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation; Yukon Lottery Commission Government House Leader Hon. Doug Graham Porter Creek North Minister responsible for Health and Social Services; Yukon Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Scott Kent Riverdale North Minister responsible for Energy, Mines and Resources; Yukon Energy Corporation; Yukon Development Corporation Hon. Currie Dixon Copperbelt North Minister responsible for Economic Development; Environment; Public Service Commission Hon. Wade Istchenko Kluane Minister responsible for Highways and Public Works Hon. Mike Nixon Porter Creek South Minister responsible for Justice; Tourism and Culture GOVERNMENT PRIVATE MEMBERS Yukon Party Darius Elias Vuntut Gwitchin Stacey Hassard Pelly-Nisutlin Hon. David Laxton Porter Creek Centre Patti McLeod Watson Lake OPPOSITION MEMBERS New Democratic Party Elizabeth Hanson Leader of the Official -

Journals of the Yukon Legislative Assembly 2021 Special Sitting

JOURNALS YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY First Session 35th Legislature 2021 Special Sitting May 11, 2021 – May 31, 2021 Speaker: The Hon. Jeremy Harper YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY First Session, 35th Legislative Assembly 2021 Special Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Jeremy Harper, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Annie Blake, MLA, Vuntut Gwitchin DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Emily Tredger, MLA, Whitehorse Centre CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Deputy Premier Government House Leader Minister of Health and Social Services; Justice Hon. Nils Clarke Riverdale North Minister of Highways and Public Works; Environment Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne- Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Public Service Southern Lakes Commission; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek Minister of Economic Development; Tourism and Culture; South Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Jeanie McLean Mountainview Minister of Education; Minister responsible for the Women’s Directorate OFFICIAL OPPOSITION Yukon Party Currie Dixon Leader of the Official Opposition -

2021 Special Sitting Index

Yukon Legislative Assembly 1st Session 35th Legislature Index to HANSARD May 11, 2021 to May 31, 2021 SPECIAL SITTING YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2021 Special Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Jeremy Harper, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Annie Blake, MLA, Vuntut Gwitchin DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Emily Tredger, MLA, Whitehorse Centre CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Deputy Premier Government House Leader Minister of Health and Social Services; Justice Hon. Nils Clarke Riverdale North Minister of Highways and Public Works; Environment Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne-Southern Lakes Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Public Service Commission; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation; French Language Services Directorate Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek South Minister of Economic Development; Tourism and Culture; Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board Hon. Jeanie McLean Mountainview Minister of Education; Minister responsible for the Women’s Directorate OFFICIAL OPPOSITION Yukon Party Currie Dixon Leader of the Official Opposition Scott Kent Official Opposition House Leader Copperbelt North Copperbelt -

The River's out - Summer's on the Way!

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 • VOL. 25, NO. 1 $1.25 KLONDIKE Happy Breakup! SUN The River's out - summer's on the way! The visiting fiddlers from Selkirk Street Elementary School chill out at Klondyke Cream & Candy, shepherded by former RSS teacher and Palace Grand performer, Grant Hartwick. Photo by Dan Davidson. in this Issue Fire on 7th Ave. 3 Kokopelle farm 6 May 2 is this year's breakup day 7 It's our birthday Cigarettes lit this Yukon Housing Part of Sunnydale returns to its Next comes the ferry launch. Max’s New month! It's been 25 unit. farming roots. Summer Hours years of Sun shine. What to see and do in Dawson! 2 New taco cart 8 Gertie's story 12 What's Your Story 22 Uffish Thoughts 4 Family Time 9 TV Guide 14-18 Business Directory & Job Board 23 Letters 5 SOVA grads 10 Stacked 20 City notices 24 P2 WEDNESDAY, MAY 14, 2014 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: hatha yoga With jOanne van nOstranD: This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many Tuesdays and Thursdays, 5:30- activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and 7SOVA p.m. E-mail [email protected] 24 hours in advance. planning, so let us know in good time! To join this listing contact the office at [email protected]. aDMin Office hOurs DAWSON CITY INTERNATIONAL GOLD SHOW: liBrarY hOurs : Monday to Thursday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. -

Tableau Statisque Canadien, Juillet 2017, Volume 15, Numéro 2

Tableau statistique canadien JUILLET 2017 VOLUME 15, NUMÉRO 2 Ce document est réalisé conjointement par : Bruno Verreault et Jean-François Fortin Direction des statistiques économiques INSTITUT DE LA STATISTIQUE DU QUÉBEC (ISQ) Pierre-Luc Gravel Direction de la francophonie et des Bureaux du Québec au Canada SECRÉTARIAT AUX AFFAIRES INTERGOUVERNEMENTALES CANADIENNES (SAIC) Pour tout renseignement concernant l’ISQ et Pour tout renseignement concernant le SAIC, les données statistiques dont il dispose, s’adresser à : s’adresser à : INSTITUT DE LA STATISTIQUE DU QUÉBEC SECRÉTARIAT AUX AFFAIRES 200, chemin Sainte-Foy INTERGOUVERNEMENTALES CANADIENNES Québec (Québec) 875, Grande Allée Est, 3e étage G1R 5T4 Québec (Québec) G1R 4Y8 Téléphone : 418 691-2401 Téléphone : 418 643-4011 ou Sans frais : 1 800 463-4090 Site Web : www.stat.gouv.qc.ca Site Web : www.saic.gouv.qc.ca Note : Le présent document est consultable en format PDF à l’adresse suivante : http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/economie/comparaisons- economiques/interprovinciales/tableau-statistique-canadien.html Par ailleurs, une mise à jour continue des tableaux qu’il contient, toujours en format PDF, apparaît à l’adresse suivante : http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/economie/comparaisons- economiques/interprovinciales/index.html Dépôt légal Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec 3e trimestre 2017 ISSN 1715-6459 (en ligne) © Gouvernement du Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec, 1996 Toute reproduction autre qu’à des fins de consultation personnelle est interdite sans l’autorisation du gouvernement du Québec. www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/droits_auteur.htm Juillet 2017 Avant-propos Le Tableau statistique canadien (TSC) est un document général de référence qui présente, de façon à la fois concise et détaillée, des données sur chaque province et territoire ainsi que sur le Canada. -

LIST of CONFIRMED CANDIDATES for the 2021 TERRITORIAL GENERAL ELECTION at the Close of Nominations on March 22 at 2 P.M

Box 2703 (A-9) Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 (867) 667-8683 1-866-668-8683 Fax (867) 393-6977 www.electionsyukon.ca [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 23, 2021 LIST OF CONFIRMED CANDIDATES FOR THE 2021 TERRITORIAL GENERAL ELECTION At the close of nominations on March 22 at 2 p.m. there were with a total of 57 candidates nominated to serve as members of the Legislative Assembly for the electoral district of their nomination. The list of confirmed candidates for the 19 electoral districts is attached. Summary of Nominations ● There is a total of 57 candidates. ● There are 19 Yukon Liberal Party candidates. ● There are 19 Yukon New Democratic Party candidates. ● There are 18 Yukon Party candidates (all electoral districts except Vuntut Gwitchin). ● There is 1 independent candidate (Mountainview). ● There are no Yukon Green Party candidates. The registration of Yukon Green Party as a registered political party will be cancelled as the Elections Act statutory threshold of a minimum of two candidates in the election was not met. After the close of nomination, there will be a drawing of lots for candidate ballot order. The ballots will be printed and distributed for use at the Advance Polls (Sunday April 4 and Monday April 5) and on Polling Day (Monday April 12). Who Are My Candidates? Candidate contact information and profiles are available at electionsyukon.ca under ‘Who are My Candidates?’ Returning office location and contact information is also included. Opportunities to Work as an Election Official Applications are available online and at any returning office. Contact Elections Yukon Dave Wilkie, Assistant Chief Electoral Officer Phone: 867-667-8683 or 1-866-668-8683 (toll free) Email: [email protected] Elections Yukon is an independent non-partisan office of the Legislative Assembly that is responsible for the administration of territorial, school council and school board elections. -

October 19, 2011 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2011 • VOL. 23, No. 13 $1.25 Hey Dawson, are you ready for hard water and KLONDIKE more of that white stuff? SUN Brazilian Jazz Heats Up Odd Fellows Hall On a tour of the Yukon, Fernanda Cunha sways her audience with smooth vocals in Dawson on October 14. See story on page 8. Photo by Alyssa Friesen in this Issue Come check out Korbo Apartment Demolition 2 TH Election Results 5 Eastcost Inspiration Up North 24 The aging building is shedding its A new chief and council have been Poet Jacob McArthur Mooney all of the NEW roof and siding. sworn in. reflects on his writer residency. toys at Max’s! City Council Brief 3 History's Shady Underbelly 8 Catch My Thrift? 15 Blast From the Past 16 Uffish Thoughts 4 Author's On Eighth 9 New Faces At SOVA 15 Kids' Page 19 Klondike Election Results 5 TV Guide 10 Stewed Prunes 16 Classifieds 19 P2 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2011 THE KLONDIKE SUN Conservation Klondike Society What to DEPOT HOURS : Sat, Sun, Mon, Wed: 1-5 p.m., Tues: 3-7 p.m. Donations of refundablesDawson City may Recreation be left on the deck Department during off hours. Info: 993-6666. SEE AND DO GYMNASTICS WITH TERRIE IS BACK! : A six week session will run Wednesdays, October 19 to November 23. $45 for the session. Instruction for in DAWSON now: ages 5+. Register through the Rec Office beginning October 3. Contact 993- Pre-school PlaygrouP: 2353. Indoor playgroup for parents and tots at Trinkle This free public service helps our readers find their way through WOMEN AND WEIGHTS: the many activities all over town. -

Chamber Meeting Day 3

Yukon Legislative Assembly Number 3 2nd Session 34th Legislature HANSARD Tuesday, April 25, 2017 — 1:00 p.m. Speaker: The Honourable Nils Clarke YUKON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2017 Spring Sitting SPEAKER — Hon. Nils Clarke, MLA, Riverdale North DEPUTY SPEAKER and CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Don Hutton, MLA, Mayo-Tatchun DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE — Ted Adel, MLA, Copperbelt North CABINET MINISTERS NAME CONSTITUENCY PORTFOLIO Hon. Sandy Silver Klondike Premier Minister of the Executive Council Office; Finance Hon. Ranj Pillai Porter Creek South Deputy Premier Minister of Energy, Mines and Resources; Economic Development; Minister responsible for the Yukon Development Corporation and the Yukon Energy Corporation Hon. Tracy-Anne McPhee Riverdale South Government House Leader Minister of Education; Justice Hon. John Streicker Mount Lorne-Southern Lakes Minister of Community Services; Minister responsible for the French Language Services Directorate; Yukon Liquor Corporation and the Yukon Lottery Commission Hon. Pauline Frost Vuntut Gwitchin Minister of Health and Social Services; Environment; Minister responsible for the Yukon Housing Corporation Hon. Richard Mostyn Whitehorse West Minister of Highways and Public Works; the Public Service Commission Hon. Jeanie Dendys Mountainview Minister of Tourism and Culture; Minister responsible for the Workers’ Compensation Health and Safety Board; Women’s Directorate GOVERNMENT PRIVATE MEMBERS Yukon Liberal Party Ted Adel Copperbelt North Paolo Gallina Porter Creek Centre Don Hutton Mayo-Tatchun -

Yukon Premier Announces Changes to Cabinet| Government of Yukon News Release

8/21/2017 Yukon Premier announces changes to Cabinet| Government of Yukon news release FOR RELEASE January 16, 20 15 Yukon Premier announces changes to Cabinet “The Cabinet ministers announced today bring a great deal of depth and experience to their new jobs, and will serve Yukoners with continued energy and commitment.” -Premier and Minister of the Executive Council Office Darrell Pasloski WHITEHORSE—Premier Darrell Pasloski has announced a strengthened and diversified Cabinet and new roles for backbencher MLAs. The changes include one new member of Cabinet, as well as a new Government House Leader, both from rural Yukon. “I am proud of our government’s accomplishments and confident th at these changes will put us in an even stronger position to meet the challenges ahead, serve Yukoners and make our territory an even better place to live, work, play and raise a family,” said Pasloski. “Our new team is built on the strengths and expertise of each minister, while also allowing them to broaden their knowledge and experience within government. This provides for both stability and fresh perspectives.” The changes announced today take effect immediately. Premier Darrell Pasloski, Executive Council Office, Finance MLA for Mountainview Minister Elaine Taylor, MLA Deputy Premier, Tourism and Culture, for Whitehorse West Women’s Directorate, French Language Services Directorate Minister Brad Cathers, MLA Justice, Yukon Development for Lake Laberge Corporation/Yukon Energy Corporation Minister Doug Graham, MLA Education for Porter Creek North Minister -

JANUARY 13, 2016 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2016 • VOL. 26, NO. 16 $1.50 Raven says the ice bridge is safe and KLONDIKE the sun's returning. SUN Seasonal Roundup and News from the Ice Bridge Gathering to see the Baby Jesus, a photo from the Christmas Eve Pageant. Photo by Betty Davidson in this Issue Saturday Painting Club 6 May the Force be with Us 8 High Tea a Great Success 9 Magazines and Lindsey Tyne profiles the Painting Mayor Potoroka explains the new Thanks to all the folks who Club. Force Main. organized and attended our fund Books Galore! raising Tea. STORE HOURS: 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday to Saturday See and Do / Authors on 8th 2 Gordon Caley Obituary 6 Palace Grand to get upgrades 11 History Hunter: Klondike Christmases 18 Christmas Eve Pageant 3 Municipal Act amendments 8 TV Guide 12-16 Classifieds & Job Board 19 Noon to 5p.m. on Sunday Uffish Thoughts: Ice Bridge issues 4 Kim Fu's public reading 10 20 years ago 17 City Notices 20 P2 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2016 THE KLONDIKE SUN Authors on 8th What to Authors on 8th poetry entry A Tribute to the AND Poetry SEE DO (Extra)ordinary Submission in DAWSON now: Women of the North By Aileen Stalker This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and planning, so let us know in good time! To join this Meetingslisting contact the office at [email protected]. IODE DAWSON CITY: Meet first Wednesday of each month at When I walk through these mossy old gravestones Rhomeoya Lof C Joyceanadian Caley atLE 7:30GION p.m. -

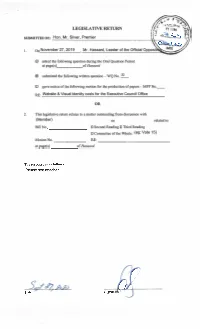

Website and Visual Identity Costs for The

______________________ LEGISLATIVE RETURN SUBMIflEDBY: Hon. Mr. Silver, Premier 1. onN0’1ember27, 2019 fl asked the following question during the Oral Question Period at page(s) of Hansard 22 U submitted the following written question — WQ No. 0 gave notice of the following motion for the production of papers — MPP No. RE: Website & Visual identity costs for the Executive Council Office OR 2. This legislative return relates to a matter outstanding from discussion with (Member) on related to: Bill No. 0 Second Reading 0 Third Reading 0 Committee of the Whole: (eg Vote 15) Motion No. RE: at page(s) of Hansard. The response is as follows: Please see attached. Date — Yukon February 7. 2020 To: Patti McLeod, Member for Watson Lake Stacey Hassard, Member for Pelly-Nisutlin Scott Kent, Member for Copperbelt South Brad Cathers, Member for Lake Laberge Wade Istchenko, Member for Kluane Geraldine Van Bibber, Member for Porter Creek Re: The Government of Yukon’s new website and visual identity cost per department. Dear Members, Thank you for your written questions on November 27. 2019, in relation to costs associated with our new website and visual identity initiative that was announced on February 19, 2018. Our new visual identity, with its consistent look and feel, is about improving the delivery of services and communicating more effectively with the public. The Government of Yukon’s visual identity embodies our territory and the people who live here through a modern and unified brand. Our former logo was more than 35 years old and was the only element of a visual identity we had. -

The Canadian Scene

CPA Activities The Canadian Scene New Yukon Speaker On January 12, 2017, the 34th Yukon Legislative Assembly convened for the first time since the November 7, 2016 general election. The first order of business on the one-day Special Sitting was the election of a Speaker. On motion of Premier Sandy Silver, seconded by Leader of the Official Opposition Stacey Hassard and Third Party House Leader Kate White, the Assembly elected Nils Clarke, the Member for Riverdale North, as its Speaker. Mr. Clarke was the sole nominee for the role. The Premier had announced his intention to nominate Mr. Clarke on December 3, 2016 at the swearing-in ceremony for Cabinet. In a December 6, 2016 news release, the Premier stated, “I am certain that [Nils Clarke’s] vast experiences have prepared him to maintain the civility and order of the assembly. I am confident Nils will carry out this critical role with the diplomacy and good will needed in the assembly…. good ideas can come from all sides and I am counting on Mr. Clarke to create a positive and dynamic environment in the assembly to support all MLAs to the job Yukoners sent us to do.” Mr. Clarke noted that he was honoured by the nomination and “look[ed] forward to helping to ensure that the work of the entire legislative assembly can proceed with civility and efficiency for the benefit of all Yukon citizens.” Nils Clarke In his address to the Assembly upon his election November, and now sits in the Assembly as a member as Speaker, Mr.