Download All Event Reports from the Everyday Sprint Als

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hammer Throw 7,26Kg Men

RESULT LIST OFFICIAL Hammer Throw 7,26kg Men RESULT NAME COUNTRY DATE VENUE WL 82.98 Paweł FAJDEK POL 30 May 2021 Stadion Śląski, Chorzów (POL) MR 80.90 Sergej Litvinov URS 20 Jun 1990 SR 78.67 Pawel Fajdek POL 17 Jun 2017 TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY START TIME 17:10 22.9°C 41.6% June 2 2021 END TIME 17:51 23.2°C 41.1% PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT POINT 1 2 3 ORD 4 5 6 S 1 Quentin Bigot FRA 1 Dec 92 5 78.95 SR 77.85 78.44 78.95 7 73.96 77.93 75.95 2 Mykhaylo Kokhan UKR 22 Jan 01 4 77.56 SB X 73.43 X 4 73.71 X 77.56 3 Bence Halász HUN 4 Aug 97 6 75.78 74.18 X X 5 73.46 75.78 75.67 4 Marcel Lomnický SVK 6 Jul 87 7 75.19 SB 74.76 X X 6 X 74.22 75.19 5 Dániel Rába HUN 24 Apr 98 2 71.63 70.63 70.27 70.70 2 69.96 X 71.63 6 Mostafa Elgamel EGY 1 Oct 88 3 71.26 71.04 X 71.26 3 X X X 7 Patrik Hájek CZE 11 Nov 98 1 70.01 68.21 66.03 X 1 68.49 67.74 70.01 Quentin Bigot won by 1.39m LEGEND WL World Lead MR Meeting Record SR Stadium Record SB Season Best ALL-TIME TOP LIST 2021 TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 86.74 Yuriy SEDYKH (URS) Neckarstadion, Stuttg 30 Aug 1986 82.98 Paweł FAJDEK (POL) Stadion Śląski, Chorzów (PO 30 May 86.04 Sergey LITVINOV (URS) Dresden (GER) 3 Jul 1986 81.98 Rudy WINKLER (USA) Hayward Field, Eugene, OR ( 24 Apr 84.90 Vadim DEVYATOVSKIY (BLR) Minsk (BLR) 21 Jul 2005 79.54 Wojciech NOWICKI (POL) Polideportivo Municipal, And 22 May 84.86 Koji MUROFUSHI (JPN) Stadion Juliska, Praha 29 Jun 2003 79.27 Sean DONNELLY (USA) Roy P. -

Hammer Throw 7,26Kg Men (IAAF Hammer Challenge)

RESULT LIST Hammer Throw 7,26kg Men (IAAF Hammer Challenge) RESULT NAME COUNTRY DATE VENUE WL 82.40 Pawel Fajdek POL 13 Jun 2017 Turku (Paavo Nurmi) MR 80.90 Sergej Litvinov 1990 TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY START TIME 15:05 19.5°C 52.1% June 17 2017 END TIME 15:59 18.5°C 55.6% PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT POINTS 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Pawel Fajdek POL 4 Jun 89 8 78.67 76.90 78.67 75.48 X X X 2 Wojciech Nowicki POL 22 Feb 89 7 76.04 72.09 73.96 73.11 76.04 X X 3 Marcel Lomnický SVK 6 Jul 87 5 74.86 72.62 73.69 74.86 73.95 X X 4 Ashraf Amjad Al-Saifi QAT 20 Feb 95 2 73.84 70.28 72.15 73.84 72.19 72.85 X 5 Nick Miller GBR 1 May 93 4 73.74 73.74 X X X 72.31 X 6 Marco Lingua ITA 4 Jun 78 3 72.73 72.39 X X 72.41 X 72.73 7 Krisztián Pars HUN 18 Feb 82 6 72.67 72.15 72.67 X 71.32 72.37 X 8 Libor Charfreitag SVK 11 Sep 77 1 67.11 X 67.11 66.84 66.24 - - Pawel Fajdek won by 2.63m ALL-TIME TOP LIST 2017 TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 86.74 Yuriy Sedykh (URS) Stuttgart 30 Aug 1986 82.40 Pawel Fajdek (POL) Turku (Paavo Nurmi) 13 Jun 86.04 Sergey Litvinov (URS) Dresden 3 Jul 1986 78.54 Wojciech Nowicki (POL) Kielce 13 May 84.90 Vadim Devyatovskiy (BLR) Minsk 21 Jul 2005 78.04 Pavel Bareisha (BLR) Doha (Hamad Bin 6 May 84.86 Koji Murofushi (JPN) Praha (Stadion 29 Jun 2003 78.00 Esref Apak (TUR) Ankara 6 Jun 84.62 Igor Astapkovich (BLR) Sevilla 6 Jun 1992 77.92 Marcel Lomnický (SVK) Coral Gables, FL 7 Apr 84.51 Ivan Tsikhan (BLR) Grodno 9 Jul 2008 77.72 Mihaíl Anastasákis (GRE) Nikíti 11 Jun 84.48 Igor Nikulin (URS) Lausanne 12 Jul 1990 77.70 Serghei Marghiev (MDA) Chisinau 26 May 84.40 Jüri Tamm (URS) Banská Bystrica 9 Sep 1984 77.51 Nick Miller (GBR) Salinas (Hartnell), CA 21 Apr 84.19 Adrián Annus (HUN) Szombathely 10 Aug 2003 77.30 Quentin Bigot (FRA) Forbach (Schlossberg) 28 May 83.93 Pawel Fajdek (POL) Szczecin (Miejski 9 Aug 2015 77.23 Marco Lingua (ITA) Torino 7 May LEGEND WL World Lead MR Meeting Record Timing & Data service by OnlineSystem s.r.o. -

Todos Los Medallistas De Los Campeonatos De Europa

TODOS LOS MEDALLISTAS DE LOS CAMPEONATOS DE EUROPA HOMBRES 100 m ORO PLATA BRONCE Viento 1934 Christiaan Berger NED 10.6 Erich Borchmeyer GER 10.7 József Sir HUN 10.7 1938 Martinus Osendarp NED 10.5 Orazio Mariani ITA 10.6 Lennart Strandberg SWE 10.6 1946 Jack Archer GBR 10.6 Håkon Tranberg NOR 10.7 Carlo Monti ITA 10.8 1950 Étienne Bally FRA 10.7 Franco Leccese ITA 10.7 Vladimir Sukharev URS 10.7 0.7 1954 Heinz Fütterer FRG 10.5 René Bonino FRA 10.6 George Ellis GBR 10.7 1958 Armin Hary FRG 10.3 Manfred Germar FRG 10.4 Peter Radford GBR 10.4 1.5 1962 Claude Piquemal FRA 10.4 Jocelyn Delecour FRA 10.4 Peter Gamper FRG 10.4 -0.6 1966 Wieslaw Maniak POL 10.60 Roger Bambuck FRA 10.61 Claude Piquemal FRA 10.62 -0.6 1969 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.49 Alain Sarteur FRA 10.50 Philippe Clerc SUI 10.56 -2.7 1971 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.26 Gerhard Wucherer FRG 10.48 Vassilios Papageorgopoulos GRE 10.56 -1.3 1974 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.27 Pietro Mennea ITA 10.34 Klaus-Dieter Bieler FRG 10.35 -1.0 1978 Pietro Mennea ITA 10.27 Eugen Ray GDR 10.36 Vladimir Ignatenko URS 10.37 0.0 1982 Frank Emmelmann GDR 10. 21 Pierfrancesco Pavoni ITA 10. 25 Marian Woronin POL 10. 28 -080.8 1986 Linford Christie GBR 10.15 Steffen Bringmann GDR 10.20 Bruno Marie-Rose FRA 10.21 -0.1 1990 Linford Christie GBR 10.00w Daniel Sangouma FRA 10.04w John Regis GBR 10.07w 2.2 1994 Linford Christie GBR 10.14 Geir Moen NOR 10.20 Aleksandr Porkhomovskiy RUS 10.31 -0.5 1998 Darren Campbell GBR 10.04 Dwain Chambers GBR 10.10 Charalambos Papadias GRE 10.17 0.3 2002 Francis Obikwelu POR 10.06 -

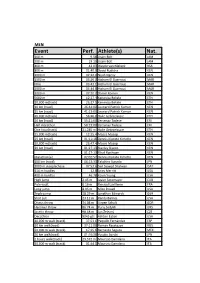

Event Perf. Athlete(S) Nat

MEN Event Perf. Athlete(s) Nat. 100 m 9.58 Usain Bolt JAM 200 m 19.19 Usain Bolt JAM 400 m 43.03 Wayde van Niekerk RSA 800 m 01:40.9 David Rudisha KEN 1000 m 02:12.0 Noah Ngeny KEN 1500 m 03:26.0 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR Mile 03:43.1 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 2000 m 04:44.8 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3000 m 07:20.7 Daniel Komen KEN 5000 m 12:37.4 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10,000 m(track) 26:17.5 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10 km (road) 26:44:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 15 km (road) 41:13:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 20,000 m(track) 56:26.0 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 20 km (road) 55:21:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI Half marathon 58:23:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI One hour(track) 21,285 m Haile Gebrselassie ETH 25,000 m(track) 12:25.4 Moses Mosop KEN 25 km (road) 01:11:18 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 30,000 m(track) 26:47.4 Moses Mosop KEN 30 km (road) 01:27:13 Stanley Biwott KEN 01:27:13 Eliud Kipchoge KEN Marathon[a] 02:02:57 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 100 km (road) 06:13:33 Takahiro Sunada JPN 3000 m steeplechase 07:53.6 Saif Saaeed Shaheen QAT 110 m hurdles 12.8 Aries Merritt USA 400 m hurdles 46.78 Kevin Young USA High jump 2.45 m Javier Sotomayor CUB Pole vault 6.16 m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Long jump 8.95 m Mike Powell USA Triple jump 18.29 m Jonathan Edwards GBR Shot put 23.12 m Randy Barnes USA Discus throw 74.08 m Jürgen Schult GDR Hammer throw 86.74 m Yuriy Sedykh URS Javelin throw 98.48 m Jan Železný CZE Decathlon 9045 pts Ashton Eaton USA 10,000 m walk (track) 37:53.1 Paquillo Fernández ESP 10 km walk(road) 37:11:00 Roman Rasskazov RUS 20,000 m walk (track) 17:25.6 Bernardo -

2013 World Championships Statistics – Men's HT

2013 World Championships Statistics – Men’s HT by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Moskva: 1) Krisztian Pars can be the first World Youth Champion to win the World Championships All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Distance Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 83.89 Ivan Tikhon BLR 1 Helsinki 2005 2 83.63 Ivan Tikhon 1 Osaka 2007 3 2 83.38 Szymon Ziolkowski POL 1 Edmonton 2001 4 3 83.06 Sergey Litvinov URS 1 Roma 1987 5 83.05 Ivan Tikhon 1 Paris 2003 6 4 82.92 Koji Murofushi JPN 2 Edmonton 2001 7 82.68 Sergey Litvinov 1 Helsinki 1983 8 5 82.60 Vadim Devyatovski BLR 2 Helsinki 2005 9 6 82.29 Primoz Kozmus SLO 2 Osaka 2007 10 81.85 Szymon Ziolkowski 1qA Edmonton 2001 11 81.78 Sergey Litvinov 1qA Roma 1987 11 7 81.78 Heinz Weis GER 1 Athinai 1997 13 8 81.70 Yuriy Sedykh URS 1 Tokyo 1991 14 9 81.64 Andrey Abduvaliyev TJK 1 Stuttgart 1993 15 10 81.60 Libor Charfreitag SVK 3 Osaka 2007 16 81.57 Vadim Devyatovskiy BLR 4 Osaka 2007 17 81.56 Andrey Abduvaliyev 1 Göteborg 1995 18 11 81.46 Andrey Skvaruk UKR 2 Athinai 1997 19 81.24 Koji Murofushi 1 Daegu 2011 20 81.20 Vadim Devyatovski 1qA Helsinki 2005 21 12 81.18 Krisztian Pars HUN 2 Daegu 2011 22 13 81.10 Igor Astapkovich BLR 2 Göteborg 1995 22 14 80.98 Tibor Gecsek HUN 3 Göteborg 1995 24 80.94 Yuriy Sedykh 2 Helsinki 1983 24 80.94 Igor Astapkovich 2 Tokyo 1991 25 80.93 Krisztian Pars 5 Osaka 2007 27 15 80.84 Jüri Tamm URS 2 Roma 1987 27 80.84 Primoz Kozmus 1 Berlin 2009 29 16 80.76 Ralph Haber GDR 3 Roma 1987 29 16 80.76 Vasiliy Sidorenko RUS 3 Athiani 1997 -

IAAF WORLD RECORDS - MEN As at 1 January 2018 EVENT PERF

IAAF WORLD RECORDS - MEN as at 1 January 2018 EVENT PERF. WIND ATHLETE NAT PLACE DATE TRACK EVENTS 100m 9.58 0.9 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin, GER 16 Aug 09 200m 19.19 -0.3 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin, GER 20 Aug 09 400m 43.03 Wayde van NIEKERK RSA Rio de Janeiro, BRA 14 Aug 16 800m 1:40.91 David Lekuta RUDISHA KEN London, GBR 9 Aug 12 1000m 2:11.96 Noah NGENY KEN Rieti, ITA 5 Sep 99 1500m 3:26.00 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Roma, ITA 14 Jul 98 1 Mile 3:43.13 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Roma, ITA 7 Jul 99 2000m 4:44.79 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Berlin, GER 7 Sep 99 3000m 7:20.67 Daniel KOMEN KEN Rieti, ITA 1 Sep 96 5000m 12:37.35 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Hengelo, NED 31 May 04 10,000m 26:17.53 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Bruxelles, BEL 26 Aug 05 20,000m 56:26.0 Haile GEBRSELASSIE ETH Ostrava, CZE 27 Jun 07 1 Hour 21,285 Haile GEBRSELASSIE ETH Ostrava, CZE 27 Jun 07 25,000m 1:12:25.4 Moses Cheruiyot MOSOP KEN Eugene, USA 3 Jun 11 30,000m 1:26:47.4 Moses Cheruiyot MOSOP KEN Eugene, USA 3 Jun 11 3000m Steeplechase 7:53.63 Saif Saaeed SHAHEEN QAT Bruxelles, BEL 3 Sep 04 110m Hurdles 12.80 0.3 Aries MERRITT USA Bruxelles, BEL 7 Sep 12 400m Hurdles 46.78 Kevin YOUNG USA Barcelona, ESP 6 Aug 92 FIELD EVENTS High Jump 2.45 Javier SOTOMAYOR CUB Salamanca, ESP 27 Jul 93 Pole Vault 6.16i Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Donetsk, UKR 15 Feb 14 Long Jump 8.95 0.3 Mike POWELL USA Tokyo, JPN 30 Aug 91 Triple Jump 18.29 1.3 Jonathan EDWARDS GBR Göteborg, SWE 7 Aug 95 Shot Put 23.12 Randy BARNES USA Los Angeles, USA 20 May 90 Discus Throw 74.08 Jürgen SCHULT GDR Neubrandenburg, GDR 6 Jun 86 Hammer Throw -

Men's 10,000M International 27.05.2016

Men's 10,000m International 27.05.2016 Start list 10,000m Time: 21:18 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1-1 Birhan NEBEBEW ETH 26:17.53 27:14.34 WR 26:17.53 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Bruxelles 26.08.05 1-2 Nicholas Mboroto KOSIMBEI KEN 26:27.85 28:37.58 AR 26:44.36 Galen RUPP USA Eugene 30.05.14 NR 26:44.36 Galen RUPP USA Eugene 30.05.14 1-3 Guye Idemo ADOLA ETH 26:17.53 WJR 26:41.75 Samuel Kamau WANJIRU KEN Bruxelles 26.08.05 1-4 Aweke AYALEW BRN 27:21.40 29:14.55 MR 26:25.97 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH 08.06.08 1-5 Tamirat TOLA ETH 26:17.53 27:22.64 DLR 26:43.16 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Bruxelles 16.09.11 1-6 Stephen SAMBU KEN 26:27.85 26:54.61 SB 27:19.71 Leule GEBRSELASSIE ETH Herzogenaurach 13.05.16 1-7 Teklemariam MEDHIN ERI 26:37.25 27:16.69 1-8 Ibrahim JEILAN ETH 26:17.53 27:02.81 1-9 Zersenay TADESE ERI 26:37.25 26:37.25 2016 World Outdoor list 1-10 Josphat Kipkoech BETT KEN 26:27.85 26:48.99 28:40.1h 27:19.71 Leule GEBRSELASSIE ETH Herzogenaurach 13.05.16 1-11 Eric JENKINS USA 26:44.36 28:59.13 27:22.28 Paul Kipngetich TANUI KEN Kobe 24.04.16 1-12 Chris DERRICK USA 26:44.36 27:31.38 27:22.99 Emmanuel KIPSANG KEN Herzogenaurach 13.05.16 1-13 Nguse AMLOSOM ERI 26:37.25 27:28.10 27:23.04 James MWANGI KEN Kobe 23.04.16 27:24.85 Hersuato MAMIYO ETH Kobe 24.04.16 1-14 Emmanuel Kipkemei BETT KEN 26:27.85 26:51.16 28:23.9h 27:25.10 Tebalu ZAWUDE HEYI ETH Herzogenaurach 13.05.16 1-15 Suguru OSAKO JPN 27:29.69 27:38.31 27:50.27 27:43.70 John MAINA KEN Yokohama 23.04.16 1-16 Mosinet GEREMEW ETH 26:17.53 27:18.86 27:43.85 Rodgers CHUMO KEN Kobe 24.04.16 1-17 -

Womenʼs 100 Metres 51 Entrants

IAAF World Championships • Biographical Entry List (may include reserves) Womenʼs 100 Metres 51 Entrants Starts Sunday, August 11 Age (Days) Born 2013 Best Personal Best 112 BREEN Melissa AUS 22y 326d 1990 11.25 -13 11.25 -13 Won sprint double at 2012 Australian Championships ... 200 pb: 23.12 -13. sf WJC 100 2008; 1 Pacific Schools Games 100 2008; 8 WSG 100 2009; 8 IAAF Continental Cup 100 2010; sf COM 100 2010; ht OLY 100 2012. 1 Australian 100/200 2012 (1 100 2010). Coach-Matt Beckenham In 2013: 1 Canberra 100/200; 1 Adelaide 100/200; 1 Sydney “Classic” 100/200; 3 Hiroshima 100; 3 Fukuroi 200; 7 Tokyo 100; 3ht Nivelles 100; 2 Oordegem Buyle 100 (3 200); 6 Naimette-Xhovémont 100; 6 Lucerne 100 ʻBʼ; 2 Belgian 100; 3 Ninove Rasschaert 200 129 ARMBRISTER Cache BAH 23y 317d 1989 11.35 11.35 -13 400 pb: 53.45 -11 (55.28 -13). 200 pb: 23.13 -08 (23.50 -13). 3 Central American & Caribbean Champs 4x100 2011. Student of Marketing at Auburn University In 2013: 1 Nassau 400 ʻBʼ; 6 Cayman Islands Invitational 200; 4 Kingston ”Jamaica All-Comers” 100; 1 Kingston 100 ʻBʼ (May 25); 1 Kingston 200 (4 100) (Jun 8); 2 Bahamian 100; 5 Central American & Caribbean Champs 100 (3 4x100) 137 FERGUSON Sheniqua BAH 23y 258d 1989 11.18 11.07 -12 2008 World Junior Champion at 200m ... led off Bahamas silver-winning sprint relay team at the 2009 World Championships 200 pb: 22.64 -12 (23.32 -13). sf World Youth 100 2005 (ht 200); 2 Central American & Caribbean junior 100 2006; 1 WJC 200 2008 (2006-8); qf OLY 200 2008; 2 WCH 4x100 2009 (sf 200, qf 100); sf WCH 200 2011; sf OLY 100 2012. -

Men's Hammer Throw Final 05.07.2021

Men's Hammer Throw Final 05.07.2021 Start list Hammer Throw Time: 18:00 Records Order Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Valeriy PRONKIN ANA 79.32 79.06 WR 86.74 Yuriy SEDYKH URS Neckarstadion, Stuttgart 30.08.86 2 Bence PÁSZTOR HUN 84.19 75.74 73.43 AR 86.74 Yuriy SEDYKH URS Neckarstadion, Stuttgart 30.08.86 3 Marcel LOMNICKÝ SVK 81.81 79.19 79.19 NR 84.19 Adrián ANNUS HUN Szombathely 10.08.03 WJB 78.33 Olli-Pekka KARJALAINEN FIN Seinäjoki 05.08.99 4 Taylor CAMPBELL GBR 80.26 78.23 78.23 MR 83.12 Paweł FAJDEK POL 07.07.15 5 Dániel RÁBA HUN 84.19 76.83 76.83 SB 82.98 Paweł FAJDEK POL Stadion Śląski, Chorzów 30.05.21 6 Eivind HENRIKSEN NOR 78.25 78.25 77.70 7 Mykhaylo KOKHAN UKR 86.74 79.96 79.96 8 Wojciech NOWICKI POL 83.93 81.85 80.86 2021 World Outdoor list 9 Bence HALÁSZ HUN 84.19 79.88 76.81 82.98 Paweł FAJDEK POL Chorzów (POL) 30.05.21 10 Paweł FAJDEK POL 83.93 83.93 82.98 82.71 Rudy WINKLER USA Eugene, OR (USA) 20.06.21 80.86 Wojciech NOWICKI POL Poznan (POL) 25.06.21 79.96 Mykhaylo KOKHAN UKR Bydgoszcz (POL) 30.06.21 79.70 Quentin BIGOT FRA Turku (FIN) 08.06.21 Medal Winners Previous Meeting 79.39 Daniel HAUGH USA Eugene, OR (USA) 20.06.21 79.27 Sean DONNELLY USA Tucson, AZ (USA) 22.05.21 2019 - IAAF World Ch. -

Detailed Results

52nd Ostrava Golden Spike Ostrava, 26 - 27 June 2013 RESULT LIST Hammer Throw 7,26kg Men (IAAF HT Challenge) RESULT NAME COUNTRY DATE VENUE WR 86.74 Yuriy Sedykh URS 30 Aug 1986 Stuttgart WL 81.02 Krisztián Pars HUN 15 Jun 2013 Szczecin MR 82.28 Krisztián Pars HUN 28 May 2012 Ostrava TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY START TIME 15:00 13.3°C 65.7% 26 June 2013 END TIME 16:14 13.6°C 66.3% PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT POINTS 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Krisztián Pars HUN 18 Feb 82 9 80.75 78.31 79.68 X 79.54 X 80.75 2 Lukáš Melich CZE 16 Sep 80 8 80.16 75.69 80.16 X 74.93 77.77 X 3 Oleksiy Sokyrskyy UKR 16 Mar 85 2 76.97 X 75.35 76.97 75.32 X X 4 Marcel Lomnický SVK 6 Jul 87 4 76.46 75.69 X 76.26 75.77 X 76.46 5 Szymon Ziólkowski POL 1 Jul 76 5 75.49 X 75.49 X 75.22 X X 6 Sergey Litvinov RUS 27 Jan 86 1 74.99 X 73.03 74.99 74.51 72.88 73.82 7 Pawel Fajdek POL 4 Jun 89 7 74.87 73.72 X X 73.87 74.87 X 8 Markus Esser GER 3 Feb 80 3 73.83 X X 73.83 72.96 72.95 - 9 Aleksey Zagorniy RUS 31 May 78 6 73.50 71.62 X 73.50 ALL-TIME TOP LIST 2013 TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE DATE 86.74 Yuriy Sedykh Stuttgart 30 Aug 1986 81.02 Krisztián Pars Szczecin 15 Jun 86.73 Ivan Tsikhan Brest, BLR 3 Jul 2005 80.71 Dilshod Nazarov Halle 25 May 86.66 Yuriy Sedykh Tallinn 22 Jun 1986 80.45 Krisztián Pars Velenje 4 Jun 86.34 Yuriy Sedykh Cork 3 Jul 1984 80.28 Lukáš Melich Szczecin 15 Jun 86.04 Sergey Litvinov Dresden 3 Jul 1986 79.99 Pawel Fajdek Szczecin 15 Jun 85.74 Sergey Litvinov Stuttgart 30 Aug 1986 79.42 Dilshod Nazarov Szczecin 15 Jun 85.68 Yuriy -

Biomechanical Analysis of Hammer Throwing: Assessment of Speed Development

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Brice, Sara Michelle (2014) Biomechanical analysis of hammer throwing: assessment of speed development. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/36292/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/36292/ Biomechanical analysis of hammer throwing: Assessment of speed development. Thesis submitted by Sara Michelle Brice BSc (Hons) JCU in January 2014 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Engineering and Physical Sciences James Cook University i Statement on the contribution of others I declare that all persons whom have contributed to this thesis have been included as co-authors for published papers or have been identified in the acknowledgments section. The author of this thesis received stipend support from both James Cook University and the Movement Sciences (Biomechanics) Department of the Australian Institute of Sport. In addition, the Australian Institute of Sport provided the equipment and facilities that were utilised for the data collection of the studies detailed in this thesis. Supervisors for the work outlined in this thesis are as follows: - Associate Professor Kevin Ness (Principal Supervisor)1 - Mr Doug Rosemond (Co-Supervisor)2 - Associate Professor Ronald White (Associate Supervisor)1 1Affililated with the School of Engineering and Physical Sciences of James Cook University 2 Affiliated with the Movement Sciences (Biomechanics) Department of the Australian Institute of Sport ii The following table is an outline of the contribution of others to the work detailed in this thesis. -

93Rd Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.Of Texas-Mike A

University of Texas at Austin Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 5:34 PM 3/27/2021 Page 1 93rd Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.of Texas-Mike A. Myers Stadium-Austin,TX - 3/25/2021 to 3/27/2021 Results Women 4x100 Meter Relay C Guidry University ================================================================ CARLETTE GUIDRY Univ/Coll Relay World: W 40.82 2012 USA American: A 40.82 2012 US National Team Collegiate: C 42.05 2018 LSU Myers Std: F 42.21 2019 USC, USC C.Brissett, A.Annelus, L-T Thomas, T.Terry TX Relays: M 42.56 2010 TX A&M, also 2013 Tarmoh, Lucas, Duncan, Mayo School Finals ================================================================ Finals 1 LSU 42.87 1) #12464 Tonea Marshall SR 2) #12469 Favour Ofili FR 3) #12465 Symone Mason JR 4) #12459 Thelma Davies FR 2 Texas 43.04 1) #13027 Serenity Douglas SR 2) #13015 Rhasidat Adeleke FR 3) #13025 Kevona Davis FR 4) #13030 Kynnedy Flannel SO 3 Texas A&M 43.87 1) #13122 Zhane Smith JR 2) #13116 Laila Owens FR 3) #13102 Immanuela Aliu SO 4) #13110 Rachel Hall SO 4 N. Carolina A&T 44.19 1) #12569 Cambrea Sturgis SO 2) #12562 Kamaya Debose-Epps SO 3) #12561 Symone Darius JR 4) #12567 Jonah Ross FR 5 Baylor 44.65 1) #12114 Ackera Nugent FR 2) #12102 Demitra Carter JR 3) #12120 Sydney Washington JR 4) #12099 Mariah Ayers FR -- Houston DQ Out of zone 1) #12325 Camille Rutherford FR 2) #13531 Taylor Bennett SR 3) #12330 Cecilia Tamayo-Garza JR 4) #12317 Tristan Evelyn SR Women 4x400 Meter Relay RichardsRoss University ================================================================ SANYA RICHARDS-ROSS