America's Introduction to Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

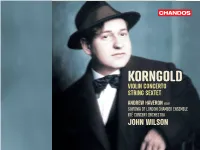

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

The Role of Contemporary Music in Instrumental Education

The role of contemporary music in instrumental education Mark Rayen Candasmy Supervisor Per Kjetil Farstad This Master’s Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, 2011 Faculty of fine arts Department of music Abstract The role of contemporary music in instrumental education discusses the necessity of renewing the curriculum of all musical studies that emphasize performance and the development of the student's instrumental abilities. A portrait of Norwegian composer Ørjan Matre is included to help exemplify the views expressed, as well as the help of theoretical analysis. Key words: contemporary music, education, musicology, ørjan matre, erich wolfgang korngold, pedagogy The role of contemporary music in instrumental education is divided into six chapters. Following the introduction, the second chapter discusses the state of musical critique and musicology, describing the first waves of modernism at the turn of the century (19 th /20 th ) and relating it to the present reality and state of contemporary music. Conclusively, it suggests possibilities of bettering the situation. The third chapter discusses the controversial aspects of Erich Wolfgang Korngold's music and life, relating it to the turbulence of the musical life during his lifetime. Studying Korngold is a unique way to outline the contradictions within Western art music that were being established during his career. The fourth chapter is a portrait of Norwegian composer Ørjan Matre and includes an analysis of his work " Handel Mixtape s". -

Student Honors Recital

BUTI ADMINISTRATION Phyllis Hoffman, Executive and Artistic Director; Shirley Leiphon, Administrative Director Lisa Naas, Director of Operations and Student Life; David Faleris, Program Administrator Emily Culler, Development, Alumni Relations, and Outreach Officer Boston University Grace Kennerly, Publications Coordinator; Manda Shepherd, Office Coordinator; Mandy Kelly, Office Intern Ben Fox, Private Lessons Coordinator; Travis Dobson, Stage Crew Manager Tanglewood Institute Matthew Lemmel, Greg Mitrokostas, Andres Trujillo, Matt Visconti, Stage Crew Michael Culler & Shane McMahon, Recording Engineers; Xiaodan Liu, Piano Technician presents YOUNG ARTISTS ORCHESTRA FACULTY AND STAFF Ryan McAdams & Paul Haas, Conductors Miguel Perez-Espejo Cardenas, Violin Coach, String Chamber Music Coordinator Caroline Pliszka, Klaudia Szlachta, Hsin-Lin Tsai, Violin Coaches, String Chamber Music Mark Berger and Laura Manko, Viola Coaches, String Chamber Music Ariana Falk and Hyun Min Lee, Cello Coaches, String Chamber Music Brian Perry, Double Bass Coach, String Chamber Music Samuel Solomon, Percussion Coordinator and Coach; Michael Israelievitch, Percussion Coach David Krauss, Brass Coach, Brass Chamber Music; Kai-yun Lu, Winds Coach, Wind Chamber Music Student Honors Recital Clara Shin, Piano Chamber Music Coach Thomas Weaver, Staff Pianist Tiffany Chang, Orchestra and Chamber Music Manager Kory Major, Orchestra Librarian and Assistant Manager YOUNG ARTISTS WIND ENSEMBLE FACULTY AND STAFF David Martins & H. Robert Reynolds, Conductors Jennifer Bill, -

0425 Program Notes

Berkshire Symphony Orchestra Saturday, April 25, 2009 8:00 p.m. Program Notes Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major, K. 488 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) is widely considered to be one of the most important Classical composers in music history. Many know of his style as playful and elegant, but he also wrote various works that were moodier and contained a Sturm und Drang quality. His 23rd Piano Concerto, K. 488 written in 1786 displays his more playful and cheerful style. The first movement is written in the double exposition form, meaning that the orchestra plays all of the major themes of the movement in the tonic key, A Major. When the pianist later comes in, Mozart fleshes out all of the themes and modulates to various keys. Mozart prominently displays the mature Classical Period stylistic qualities in this first movement. With the rise of the middle class, composers found that pieces that had a simple but melodic line with a tuneful quality to them were widely accepted by the public. One of Mozart’s most characteristic traits is his tendency to create small variations when repeating a phrase or a theme. This transformative quality is especially apparent in many themes of this concerto. Mozart himself probably played this concerto directly after it was written. In 1781 he paved a new road for composers because he decided to become a free-lance artist. Rebelling against the patronage system, Mozart wrote concertos that he would debut to the public to make a living. I chose this piece because I feel it is the best representation of Mozart’s elegant and deceptively simplistic style. -

Daniel Hope Releases Escape to Paradise: the Hollywood Album on DG, Sep 2

Daniel Hope releases Escape to Paradise: The Hollywood Album on DG, Sep 2 DG press contact: Olga Makrias 212-333-1485 [email protected] 21C Media press contact: Glenn Petry 212-625-2038 [email protected] Daniel Hope Releases Escape to Paradise: The Hollywood Album – Including a Performance by Sting – on Deutsche Grammophon, September 2 “Daniel Hope is a force to be reckoned with.” (Gramophone) On September 2, Deutsche Grammophon releases Classical BRIT-Award-winner Daniel Hope’s new recording, Escape to Paradise: The Hollywood Album, in the US (The album is released in Europe a day earlier.) The British violinist has a “thriving solo career” per the New York Times, which “has been built on inventive programming and a probing interpretive style.” The new release draws on Hope’s extensive research into European composers - among them Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Miklós Rózsa, Hanns Eisler, and Franz Waxman to name a few - who fled fascist persecution to relocate to Los Angeles where they penned some of the 20th century’s most iconic film scores. Recorded with Alexander Shelley leading the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic and guest artists including vocalists Sting and Max Raabe, Hope’s unprecedented new collection juxtaposes examples of the émigré composers’ film and concert music with selections by those they influenced – like leading contemporary movie composers John Williams, Ennio Morricone, and Thomas Newman – in a nostalgic search for the quintessentially lavish “Hollywood sound.” Daniel Hope releases Escape to Paradise: The Hollywood Album on DG, Sep 2 Page 2 of 5 A trailer for Escape to Paradise is available here Neither this spirit of investigation nor the Holocaust theme mark new territory for Hope, a musical activist whose commanding artistry goes hand in hand with a deep commitment to humanitarian causes. -

570183Bk Son of Kong 15/7/07 5:40 PM Page 12

570184bk Bette:570183bk Son of Kong 15/7/07 5:40 PM Page 12 Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky and Nikolay Tcherepnin. The orchestra also stays busy recording music for contemporary films. Critical accolades for the orchestra’s wide-ranging recordings are frequent, including its important film music re-recordings with conductor William Stromberg and reconstructionist John Morgan for Marco Polo. Fanfare critic Royal S. Brown, reviewing the complete recording of Hans J. Salter and Paul Dessau’s landmark House of Frankenstein score, saluted the CD as a “valuable document on the kind of craftsmanship and daring in film scoring that passed by all but unnoticed because of the nature of the films.” Film Score Monthly praised the orchestra’s recording of Korngold’s Another Dawn score, adding that “Stromberg, Morgan and company could show some classical concert conductors a thing or two on how Korngold should be played and recorded.” The same magazine described a recording of suites from Max Steiner’s music for Virginia City and The Beast With Five Fingers as “full-blooded and emphatic.” And Rad Bennett of The Absolute Sound found so much to praise in the orchestra’s film music series he voiced a fervent desire that Marco Polo stay put in Moscow and “record film music forever”. Many of these recordings are now being reissued in the Naxos Film Music Classics series. William Stromberg (behind) and John Morgan 8.570184 570184bk Bette:570183bk Son of Kong 15/7/07 5:40 PM Page 2 Max Steiner (1888–1971) passed away July 2002. She was always excited about memories for her. -

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA a JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Cristian Măcelaru, Conductor January 21, 2017 LEONARD BERNSTEIN Symp

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA A JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Cristian Măcelaru, conductor January 21, 2017 LEONARD BERNSTEIN Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD The Sea Hawk Suite Main Title Reunion The Albatross The Throne Room The Orchid Gold Caravan Duel Part I Duel continued Freedom INTERMISSION VARIOUS Hollywood Scores: “Perlman Plays Hollywood” arr. John Williams “As Time Goes By” from Casablanca “Love Theme” from Cinema Paradiso “Theme” from Far and Away “Main Title” from Out of Africa “Marion and Robin Love Theme” from The Adventures of Robin Hood “Theme” from Sabrina “Theme” from Schindler’s List “Tango (Por Una Cabeza)” from Scent of a Woman Itzhak Perlman, violin MUSIC FOR THE MOVIES Even in the days of silent films, movie-makers recognized that the experience on the screen could be enhanced with musical accompaniment, and movie theaters hired pianists and organists to improvise music that would underline or intensify what the audiences were experiencing on the screen. (The teenaged Dmitri Shostakovich supported his family by playing piano in freezing movie halls in Leningrad in the early 1920s.) With the arrival of talkies, it became possible to compose and incorporate music directly into each movie, and a new art form was born. This concert offers film music by several different composers, but featuring two in particular. Leonard Bernstein would have written more for the movies, but he found the experience difficult; On the Waterfront was his only film score. Two decades earlier, Erich Wolfgang Korngold moved from Vienna to Hollywood and completely changed our sense of what film music might be, writing music so distinct that it can stand alone in the concert hall. -

Erich Korngold's Discursive Practices: Musical Values in the Salon Community from Vienna to Hollywood

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2016 Erich Korngold's Discursive Practices: Musical Values in the Salon Community from Vienna to Hollywood Bonnie Lynn Finn University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Finn, Bonnie Lynn, "Erich Korngold's Discursive Practices: Musical Values in the Salon Community from Vienna to Hollywood. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4036 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Bonnie Lynn Finn entitled "Erich Korngold's Discursive Practices: Musical Values in the Salon Community from Vienna to Hollywood." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel M. Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Leslie C. Gay Jr., Victor Chavez Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and -

1936: Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Anthonyadverse

Krumbholz, MUSC 108 Academy Awards for Best Score 1936: Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Anthony Adverse 1937: Charles Previn, 100 Men and a Girl 1938: Alfred Newman, Alexander's Ragtime Band (scoring) 1938: Erich Wolfgang Korngold, The Adventures of Robin Hood (original score) 1939: Herbert Stothart, The Wizard of Oz (original score) 1939: Richard Hageman, et al., Stagecoach (scoring) 1940: Alfred Newman, Tin Pan Alley (scoring) 1940: Leigh Harline, Paul Smith, and Ned Washington, Pinocchio (original score) 1941: Bernard Hermann, All That Money Can Buy 1942: Max Steiner, Now Voyager 1943: Alfred Newman, The Song of Bernadette 1944: Max Steiner, Since You Went Away 1945: Miklos Rozsa, Spellbound 1946: Hugo Friedhofer, The Best Years of Our Lives 1947: Alfred Newman, Mother Wore Tights 1947: Miklos Rozsa, A Double Life 1948: Brian Easdale, The Red Shoes 1949: Aaron Copland, The Heiress 1950: Franx Waxman, Sunset Boulevard 1951: Franz Waxman, A Place in the Sun 1952: Alfred Newman, With a Song in My Heart 1952: Dimitri Tiomkin, High Noon 1953: Alfred Newman, Call Me Madam 1953: Bronislau Kaper, Lili 1954: Dimitri Tiomkin, The High and the Mighty 1955: Alfred Newman, Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing 1956: Victor Young, Around the World in Eighty Days 1957 Malcolm Arnold, The Bridge on the River Kwai 1958: Dimitri Tiomkin, The Old Man and the Sea 1959: Miklos Rozsa, Ben-Hur 1960: Ernest Gold, Exodus 1961: Henry Mancini, Breakfast at Tiffany's 1962: Maurice Jarre, Lawrence of Arabia 1963: John Addison, Tom Jones 1964: Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman, Mary Poppins 1965: Maurice Jarre, Dr. -

Romantic Voices Danbi Um, Violin; Orion Weiss, Piano; with Paul Huang, Violin

CARTE BLANCHE CONCERT IV: Romantic Voices Danbi Um, violin; Orion Weiss, piano; with Paul Huang, violin July 30 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Violinist Danbi Um embodies the tradition of the great Romantic style, her Sunday, July 30 natural vocal expression coupled with virtuosic technique. Partnered by pia- 6:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School nist Orion Weiss, making his Music@Menlo debut, she offers a program of music she holds closest to her heart, a stunning variety of both favorites and SPECIAL THANKS delightful discoveries. Music@Menlo dedicates this performance to Hazel Cheilek with gratitude for her generous support. ERNEST BLOCH (1880–1959) JENŐ HUBAY (1858–1937) Violin Sonata no. 2, Poème mystique (1924) Scènes de la csárda no. 3 for Violin and Piano, op. 18, Maros vize (The River GEORGE ENESCU (1881–1955) Maros) (ca. 1882–1883) Violin Sonata no. 3 in a minor, op. 25, Dans le caractère populaire roumain (In FRITZ KREISLER (1875–1962) Romanian Folk Character) (1926) Midnight Bells (after Richard Heuberger’s Midnight Bells from Moderato malinconico The Opera Ball) (1923) Andante sostenuto e misterioso Allegro con brio, ma non troppo mosso ERNEST BLOCH Avodah (1928) INTERMISSION JOSEPH ACHRON (1886–1943) ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD (1897–1957) Hebrew Dance, op. 35, no. 1 (1913) Four Pieces for Violin and Piano from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s CONCERTS BLANCHE CARTE Danbi Um, violin; Orion Weiss, piano Much Ado about Nothing, op. 11 (1918–1919) Maiden in the Bridal Chamber March of the Watch PABLO DE SARASATE (1844–1908) Intermezzo: Garden Scene Navarra (Spanish Dance) for Two Violins and Piano, op. -

Hollywood's Transformation of the Leitmotiv By

From Alberich to Gollum: Hollywood’s Transformation of the Leitmotiv by Andrew J. Reitter A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in Music History and Literature with Distinction Spring 2013 © 2013 Andrew J. Reitter All Rights Reserved From Alberich to Gollum: Hollywood’s Transformation of the Leitmotiv by Andrew J. Reitter Approved: __________________________________________________________ Philip Gentry, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Russell Murray, Ph.D. Committee member from the Department of Music Approved: __________________________________________________________ James Anderson, Ph.D. Committee member from the Department of Music Approved: __________________________________________________________ Leslie Reidel, M.F.A. Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: __________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge all of my readers for their guidance and support throughout this endeavor. I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Philip Gentry for his inspirational teaching and advising, which has resulted in my decision to pursue higher education in the field of Musicology, and I would also like to thank him for his steady hand and patience in working with me over the last few years. Additionally,