Preview Copy Film Composers in the Concert Hall .Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Academy Committees 19~5 - 19~6

ACADEMY COMMITTEES 19~5 - 19~6 Jean Hersholt, president and Margaret Gledhill, Executive Secretary, ex officio members of all committees. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE SPECIAL DOCUMENTARY Harry Brand COMMITTEE lBTH AWARDS will i am Do z i e r Sidney Solow, Chairman Ray Heindorf William Dozier Frank Lloyd Philip Dunne Mary C. McCall, Jr. James Wong Howe Thomas T. Moulton Nunnally Johnson James Stewart William Cameron Menzies Harriet Parsons FINANCE COMMITTEE Anne Revere Joseph Si strom John LeRoy Johnston, Chairman Frank Tuttle Gordon Hollingshead wi a rd I h n en · SPECIAL COMMITTEE 18TH AWARDS PRESENTATION FILM VIEWING COMMITTEE Farciot Edouart, Chairman William Dozier, Chairman Charles Brackett Joan Harrison Will i am Do z i e r Howard Koch Hal E1 ias Dore Schary A. Arnold Gillespie Johnny Green SHORT SUBJECTS EXECUTIVE Bernard Herzbrun COMMI TTEE Gordon Hollingshead Wiard Ihnen Jules white, Chairman John LeRoy Johnston Gordon Ho11 ingshead St acy Keach Walter Lantz Hal Kern Louis Notarius Robert Lees Pete Smith Fred MacMu rray Mary C. McCall, Jr. MUSIC BRANCH EXECUTIVE Lou i s Mesenkop COMMITTEE Victor Milner Thomas T. Moulton Mario Caste1nuovo-Tedesco Clem Portman Adolph Deutsch Fred Ri chards Ray Heindorf Frederick Rinaldo Louis Lipstone Sidney Solow Abe Meyer Alfred Newman Herbert Stothart INTERNATIONAL AWARD Ned Washington COMM I TTEE Charles Boyer MUSIC BRANCH HOLLYWOOD Walt Disney BOWL CONCERT COMMITTEE wi 11 i am Gordon Luigi Luraschi Johnny Green, Chairman Robert Riskin Adolph Deutsch Carl Schaefer Ray Heindorf Robert Vogel Edward B. Powell Morris Stoloff Charles Wolcott ACADEMY FOUNDATION TRUSTEES Victor Young Charles Brackett Michael Curtiz MUSIC BRANCH ACTIVITIES Farc i ot Edouart COMMITTEE Nat Finston Jean Hersholt Franz Waxman, Chairman Y. -

Maurice Jarre Almost an Angel Mp3, Flac, Wma

Maurice Jarre Almost An Angel mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Classical / Stage & Screen Album: Almost An Angel Country: US Released: 1990 Style: Score, Neo-Classical, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1908 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1250 mb WMA version RAR size: 1436 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 352 Other Formats: MP2 WMA MP1 APE DXD DTS VOC Tracklist Hide Credits Some Wings A1 –Vanessa Williams Lyrics By – Ray UnderwoodMusic By – Maurice JarreRecorded By [Vocals] – Jerry Brown* A2 –Maurice Jarre Almost An Angel A3 –Maurice Jarre Fly A4 –Maurice Jarre Rose And Terry The Mafia Bluff B1 –Maurice Jarre Composed By [Contains Love Theme From The Godfather] – Nino Rota B2 –Maurice Jarre Steve's Run B3 –Maurice Jarre Let There Be Light Credits Composed By, Conductor – Maurice Jarre Contractor, Coordinator [Music] – Leslie Morris Edited By [Digitally] – Dave Collins Executive-Producer – Robert Townson Liner Notes – John Cornell Mixed By – Shawn Murphy Mixed By [Assisted By] – Sharon Rice Other [Assistant To Maurice Jarre] – Pat Russ Producer – Maurice Jarre Recorded By [Music] – Robert Fernandez, Shawn Murphy Supervised By [Production Supervisor] – Tom Null Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 30206-5307-4 2 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Almost An Angel (Original Maurice Varèse VSD-5307 Motion Picture Soundtrack) VSD-5307 US 1990 Jarre Sarabande (CD, Album) Almost An Angel (Original Maurice Varèse VS-5307 Motion Picture Soundtrack) VS-5307 Germany 1990 Jarre Sarabande (LP, Album) Maurice -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Christopher Slaski Applied Music

Christopher Slaski Applied Music: The Challenge Of Composing For Films Gothenburg/Sweden, 10th April 2015 CHRISTOPHER SLASKI It’s a great pleasure to be here. I’ve been working in film and applied music for almost 20 years, having started early, when still at university. My beginnings in music was as a pianist and organist. From the age of five, I studied the piano and I began composing in my early teens. The life of a touring concert musician didn’t really appeal to me so I thought: How am I going to make my living out of music? I began to discover there was often very interesting music accompanying films, and I started listening to it with greater attention. I soon realised that this was what I want to do. But how to get into it ? I won’t dwell on that today. That’s for another lecture! Today we’re going to concentrate on the challenges that a film composer has to face, and the difference between composing absolute music and applied music. By ‘applied music’ I am referring to film music or music for advertising, television or theatre, that is to say, music that is written with the intention of applying it to something else. I’m going to try to cover a number of different areas that I believe are important, and give some illustrations using projects I’ve worked on. If anyone has any questions, we’ll leave them till the end when we we’ll have ten minutes or so to have a discussion. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

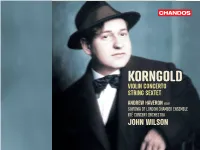

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

André Previn Tippett's Secret History

TIPPETT’S SECRET HISTORY ANDRÉ PREVIN The fascinating story of the composer’s incendiary politics Our farewell to the musical legend 110 The world’s best-selling classical music magazine reviews by the world’s finest critics See p72 Bach at its best! Pianist Víkingur Ólafsson wins our Recording of the Year Richard Morrison Preparing students for real life Classically trained America’s railroad revolution Also in this issue Mark Simpson Karlheinz Stockhausen We meet the young composer Alina Ibragimova Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet Ailish Tynan and much more… First Transcontinental Railroad Carriage made in heaven: Sunday services on a train of the Central Pacific Railroad, 1876; (below) Leland Stanford hammers in the Golden Spike Way OutWest 150 years ago, America’s First Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Brian Wise describes how music thrived in the golden age of train travel fter the freezing morning of 10 May Key to the railroad’s construction were 1869, a crowd gathered at Utah’s immigrant labourers – mostly from Ireland and Promontory Summit to watch as a China – who worked amid avalanches, disease, A golden spike was pounded into an clashes with Native Americans and searing unfinished railroad track. Within moments, a summer heat. ‘Not that many people know how telegraph was sent from one side of the country hard it was to build, and how many perished to the other announcing the completion of while building this,’ says Zhou Tian, a Chinese- North America’s first transcontinental railroad. American composer whose new orchestral work It set off the first coast-to-coast celebration, Transcend pays tribute to these workers. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S.