Identifying the Endgame

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

Diversity in the Arts

Diversity In The Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies A Study by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland September 2015 Authors’ Note Introduction The DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the In 1999, Crossroads Theatre Company won the Tony Award University of Maryland has worked since its founding at the for Outstanding Regional Theatre in the United States, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 to first African American organization to earn this distinction. address one aspect of America’s racial divide: the disparity The acclaimed theater, based in New Brunswick, New between arts organizations of color and mainstream arts Jersey, had established a strong national artistic reputation organizations. (Please see Appendix A for a list of African and stood as a central component of the city’s cultural American and Latino organizations with which the Institute revitalization. has collaborated.) Through this work, the DeVos Institute staff has developed a deep and abiding respect for the artistry, That same year, however, financial difficulties forced the passion, and dedication of the artists of color who have theater to cancel several performances because it could not created their own organizations. Our hope is that this project pay for sets, costumes, or actors.1 By the following year, the will initiate action to ensure that the diverse and glorious quilt theater had amassed $2 million in debt, and its major funders that is the American arts ecology will be maintained for future speculated in the press about the organization’s viability.2 generations. -

Lou Bellamy 2006 Distinguished Artist

Lou Bellamy 2006 Distinguished Artist Lou Bellamy 2006 Distinguished Artist The McKnight Foundation Introduction spotlight is a funny thing. It holds great potential to expose and clarify whatever lies within its glowing circle—but for that to happen, eyes outside the pool of light must be focused Aon what’s unfolding within. Theater gains meaning only through the community that generates, participates in, and witnesses it. For McKnight Distinguished Artist Lou Bellamy and his Penumbra Theatre Company, using one’s talents to connect important messages to community is what art is all about. Bellamy believes that theater’s purpose is to focus the community’s attention and engage people in the issues we face together. He relishes the opportunity life has presented to him: to work in an African American neighborhood and develop art responsive to that neighborhood, while presenting ideas that are universal enough to encourage a world of diverse neighborhoods to take notice. This is not a spectator sport. Bellamy is a strong proponent of active art, art driven to do something. Ideally, audience members should see what’s onstage and listen to the message, then carry that message with them when they leave the theater. “You put all these people in a room,” he has said, “turn out the lights, and make them all look at one thing. You’ve got something powerful in that room.” More than 40,000 people experience that power annually, in Penumbra’s 265-seat theater in St. Paul. Universal messages are not crafted through European American templates only, and Bellamy recognizes that presenting a multifaceted reality means showing all the rays of light that pass through it. -

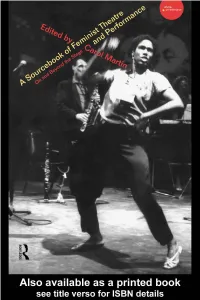

A Sourcebook on Feminist Theatre and Performance: on and Beyond the Stage/Edited by Carol Martin; with an Introduction by Jill Dolan

A SOURCEBOOK OF FEMINIST THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE A Sourcebook of Feminist Theatre and Performance brings together key articles first published in The Drama Review (TDR), to provide an intriguing overview of the development of feminist theatre and performance. Divided into the categories of “history,” “theory,” “interviews,” and “texts,” the materials in this collection allow the reader to consider the developments of feminist theatre through a variety of perspectives. This book contains the seminal texts of theorists such as Elin Diamond, Peggy Phelan, and Lynda Hart, interviews with performance artists including Anna Deveare Smith and Robbie McCauley, and the full performance texts of Holly Hughes’ Dress Suits to Hire and Karen Finley’s The Constant State of Desire. The outstanding diversity of this collection makes for an invaluable sourcebook. A Sourcebook of Feminist Theatre and Performance will be read by students and practitioners of theatre and performance, as well as those interested in the performance of sexualities and genders. Carol Martin is Assistant Professor of Drama at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. WORLDS OF PERFORMANCE What is a “performance”? Where does it take place? Who are the participants? Not so long ago these were settled questions, but today such orthodox answers are unsatisfactory, misleading, and limiting. “Performance” as a theoretical category and as a practice has expanded explosively. It now comprises a panoply of genres ranging from play, to popular entertainments, to theatre, dance, and music, to secular and religious rituals, to “performance in everyday life,” to intercultural experiments, and more. For nearly forty years, The Drama Review (TDR), the journal of performance studies, has been at the cutting edge of exploring these questions. -

The Department of Theater Year in Review 2013-2014

The Department of Theater Year In Review 2013-2014 1 Table of Contents 2013-2014 Our Season Page 3 Faculty and Staff News and Achievements Page 8 Outreach Page 15 Curricular Enhancement Page 16 Development Page 18 News and Achievements Page 22 Looking ahead to 2014-2015 Our Season Page 25 People Page 27 Outreach Page 28 Development Page 29 Appendix: 2013-2014 Season Survey Analysis 2 2013-2014 Our Season Box office results for 2013-2014 The 2013-2014 season in box office numbers was a dramatic one. While the Red Sox run at the World Series gave us lower-than-hoped-for numbers for our season opener, the show was rapturously reviewed, and our number rebounded beyond our projections thanks to our two biggest shows, Street Scene and Peter Pan, which brought in huge crowds and box office receipts. Of particular note, also, was our Peter Pan matinee, which was a sell-out and drew a number of elementary schools in addition to our usual middle- and high-school crowd. THE SHOW SPACE EST # ACTUAL +/- Attendance The Liar Rand $6,000.00 $3,924.20 $(2,075.80) 682 Detroit Curtain $4,500.00 $3,583.36 $(916.64) 576 Street Scene Rand $5,500.00 $10,634.77 $5,134.77 1788 Play Lab Curtain $2,000.00 $1,290.54 $(709.46) 387 Peter Pan Rand $6,000.00 $11,258.63 $5,258.63 1681 Peter Pan Matinee Rand $1,000.00 $1,932.00 $932.00 365 $25,000.00 $32,623.50 less 7.2% $1,800.00 $2,348.89 TOTAL BOX OFFICE $23,200.00 $30,274.61 $7,074.61 5479 That outcome, we are pleased to note, compares favorably to last year’s box office total of $29,543.37. -

Inside | FLY a Behind-The-Curtain Look at the Artists, the Company and the Art Form of This Production

® INSIDE BEFORE EN ROUTE AFTER inside | FLY A behind-the-curtain look at the artists, the company and the art form of this production. COMMON CORE STANDARDS NEW YORK STATE STANDARDS BLUEPRINT FOR THE ARTS Speaking and Listening: 1; 2; 6 Arts: 4 Theater: Developing Theater Literacy; Making Language: 1; 4; 6 English Language Arts: 1; 4 Connections This section is part of a full NEW VICTORY® SCHOOL TOOLTM Resource Guide. For the complete guide, including information about the NEW VICTORY Education Department check out: NEWVICTORY.ORG/SCHOOLTOOLS ® THE NEW VICTORY THEATER / NEWVICTORY.ORG/SCHOOLTOOL © THE NEW 42ND STREET, INC. 5 ® INSIDE BEFORE EN ROUTE AFTER inside | FLY American History + Tap Dance + Video Projections + Perseverance = WHERE IN THE WORLD IS FLY FROM? [ FLY ] NORTH AMERICA X ATLANTIC The year is 1943: Allied forces liberate Rome; British and US OCEAN troops storm the beaches of Normandy; and, on an airfield PACIFIC in Alabama, four brave young men join the first black military OCEAN SOUTH AMERICA aviators in United States history. FLY, a theatrical action-adventure, beautifully employs dance and video projection to illuminate the tremendous courage and resilience of the Tuskegee Airmen. From training to combat, experience the anguish, fears and triumphs of a brotherhood who fought for freedom abroad—and at home. Thrilling, inspired and uplifting, FLY soars. FLY CLOSER LOOK AT X NEW BRUNSWICK • Crossroads Theatre Company, based in New Jersey, was the first African American theater to receive the prestigious Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre in 1999. NEW JERSEY • Established in 1978, Crossroads Theatre Company has produced over 100 works, many of which were world-premiere productions by leading African and African American artists. -

Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms On/Through the Twenty- First Century New York Commercial Stage

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms on/through the Twenty- First Century New York Commercial Stage Stefanie A. Jones The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2025 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ACTS OF PROVOCATION: POPULAR ANTIRACISMS ON/THROUGH THE TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY NEW YORK COMMERCIAL STAGE by STEFANIE A. JONES A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 S A Jones © 2017 STEFANIE A. JONES ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii S A Jones Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms on/through the Twenty-First Century New York Commercial Stage Stefanie A. Jones This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________ ____________________________________ Date David Savran Chair of Examining Committee _____________ ____________________________________ Date Peter Eckersall Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Kandice Chuh Robert Reid-Pharr James Wilson THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii S A Jones ABSTRACT Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms on/through the Twenty-First Century New York Commercial Stage by Stefanie A. Jones Advisor: David Savran This is an abolitionist feminist study of the role of liberalism in the twenty-first century political economy. -

Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2019 TCG NATIONAL CONFERENCE IMPACT REPORT 1 Called the “Magic City” after its population exploded in the 20th century , Miami’s true constant has always been change. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the city’s population grew from just 10% residents of color to almost 90%, and by 2000 nearly 60% were immigrants. Today, Miami remains the third largest immigration port city in the U.S. With such ballooning diversity comes an abundance of creative expression. The city’s pulpy, “Miami Vice” style exterior belies its cultural complexity; in truth, it’s always shifting, and its artists, storytellers, and cultural leaders are there to capture it all. From June 5–7, 2019, TCG convened almost 900 theatre practitioners from across the U.S. and beyond our borders at the InterContinental Hotel in downtown Miami, each one looking to manage their own relationship to ever-present change. Against the backdrop of Miami’s plurality of global cultures and artistic disciplines, we focused intently on three programmatic areas: Audience and Community Engagement as part of our continuing Audience (R)Evolution initiative funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Well-being and Wellness; and Theatre Journalism, with the support of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. As part of and in parallel to these areas, we addressed our field’s most pressing issues in our many professional development sessions, all while nurturing its growing commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pre- and Post-Conferences convened university leaders, education staff, and producers of theatre for young audiences to discuss our field’s dedication to and support of the incoming generations of theatre-makers and -goers. -

August Wilson and the Contemporary Theatre Interviewed by Yvonne Shafer

Fall 1997 23 August Wilson and the Contemporary Theatre Interviewed by Yvonne Shafer In April 1997 August Wilson's play Jitney opened at the Crossroads Theatre in New Brunswick, New Jersey preparatory to a New York opening scheduled for the fall. Wilson was in residence at the theatre. The play is the seventh of his to open in New York and is part of his plan for a cycle of plays dealing with each of the decades of the twentieth century. Beginning with Ma Rainey's Black Bottom in 1985, each of his plays has won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award as Best Play of the Year. He has also won two Pulitzer Prizes as well as Tony Awards. He is one of seven American playwrights to win more than one Pulitzer Prize and one of only three African American playwrights to be so honored. By 1988 he was described as the foremost dramatist of the American black experience and by 1990 the most acclaimed playwright of his time. Wilson was born in 1945 in Pittsburgh. He dropped out of high school and worked at various jobs. He educated himself in the public library and was particularly attracted to poetry. He first wrote poems, then turned to writing plays. His first success in theatre came in 1982 when Ma Rainey 's Black Bottom was accepted at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center's Playwright Conference and Lloyd Richards took an interest in directing it for Yale Repertory and then bringing it in to New York. By this time Wilson had moved to St. -

2015/16 Season 2015/16 Seasonadapted for the Stage | Byarena Cheryl L

SWEAT 2015/16 SEASON 2015/16 SEASONADAPTED FOR THE STAGE | BYARENA CHERYL L. WEST | BASED STAGE ON THE ORIGINAL SCREENPLAYGIVES BY DOUG YOUATCHISON MORE OFF-BROADWAY SMASH A PERSONAL MUSICAL JOURNEY Photo of Margaret Colin Powell. by Tony Photo of Benjamin Scheuer by Matthew Murphy. THE CITY OF CONVERSATION THE LION BY ANTHONY GIARDINA | DIRECTED BY DOUG HUGHES | WITH MARGARET COLIN WRITTEN / PERFORMED BY BENJAMIN SCHEUER | DIRECTED BY SEAN DANIELS JANUARY 29 — MARCH 6, 2016 PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH EVA PRICE | FEBRUARY 26 — APRIL 10, 2016 TONY-WINNING DRAMA PULITZER-WINNING DRAMA Photo of Jack Willis by Jenny Graham. ALL THE WAY DISGRACED BY ROBERT SCHENKKAN | DIRECTED BY KYLE DONNELLY BY AYAD AKHTAR | DIRECTED BY TIMOTHY DOUGLAS APRIL 1 — MAY 8, 2016 APRIL 22 — MAY 29, 2016 ORDER TODAY! 202-488-3300 | WWW.ARENASTAGE.ORG ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY CHERYL L. WEST | BASED ON THE ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY BY DOUG ATCHISON SWEAT TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Producer 7 Dramaturg’s Note 9 Title Page 11 Time and Place, Cast List, For this Production 12 Who’s Who - Cast 14 Who’s Who - Creative Team ARENA STAGE 1101 Sixth Street SW 19 Arena Stage Leadership Washington, DC 20024-2461 ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 20 Board of Trustees SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 TTY 202-484-0247 20 Thank You – Next Stage Campaign www.arenastage.org © 2015 Arena Stage. All editorial and advertising 21 Thank You – The Full Circle Society material is fully protected and must not be reproduced in any 22 Thank You – The Annual Fund manner without written permission. -

LBT CV January 2017 Public

Lisa B. Thompson, Ph.D. Education Ph. D. Program in Modern Thought & Literature 2000 Stanford University M. A. African American Studies 1991 University of California, Los Angeles B. A. English 1988 University of California, Los Angeles Academic Appointments The University of Texas at Austin Associate Professor 2012-present Department of African and African Diaspora Studies Affiliations: Department of English, Department of Theatre and Dance Performance as Public Practice Program; the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies; and Center for Women and Gender Studies University at Albany, State University of New York Associate Professor 2009-2012 Department of English Affiliation: Department of Women’s Studies Assistant Professor 2001-2009 Department of English Affiliation: Department of Women’s Studies Administrative Appointments The University of Texas at Austin John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies Associate Director 2013-2015 Publications Books Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and the New African American Middle Class, University of Illinois Press, 2009. Awarded Honorable Mention in competition for the 2010 Gloria E. Anzaldúa Book Prize, National Women’s Studies Association. Single Black Female. Samuel French, Inc., 2012. Peer-Reviewed Book Chapters “Queering Black Male Identity and Desire: Jeffrey McCune’s Dancin’ the Down Low.” Blacktino Queer Performance. Eds. E. Patrick Johnson and Ramon Rivera-Servera, Duke University Press, 2016. 320-330. Lisa B. Thompson, 2 “Black Ladies and Black Magic Women.” From Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle Class Performances. Eds. Vershawn Young with Bridget Tsemo. Wayne State University Press, 2011, 287-307. “Easy Women: Black Beauty in Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins Mystery Series.” Reprint. -

2015 National Black Theatre Festival® Please Type Or Print Information Clearly in Ink

HOTELS AND TRANSPORTATION Marriott Twin City Quarter (Host Hotel) Historic Brookstown Inn 425 N. Cherry Street, W-S, NC 27101 200 Brookstown Avenue, W-S, NC 27101 336.725.3500; 877.888.9762 336.725.1120 NBTF Rate: $174, Single/Double NBTF Rate: $147/single, $141/double *Give discount Code: BTF Cut-off date: 6/27/15 to receive Festival Group Discount Holiday Inn Express Downtown West Embassy Suites Twin City Quarter 110 Miller Street, W-S, NC 27103 (Host Hotel) 800.315.2621 460 N. Cherry Street, W-S, NC 27101 NBTF Rate: $129.99, Single/Double 336.724.2300; 800.362.2779 Cut-off date: 7/13/15 NBTF Rate: $204.00 All rooms are full suites. La Quinta Inn 2020 Griffith Road Best Western Plus 336.765-8777 3330 Silas Creek Parkway, W-S, NC 27103 NBTF Rate: $79.90, Single/Double 336.893.7540 NBTF Rate: $129, Single/Double Quality Inn (Coliseum Area) Cut-off date: 6/27/15 531 Akron Drive, W-S, NC 27105 336.767.8240; 800.841.0121 Comfort Suites NBTF Rate: $69.99, Single/Double 200 Capitol Lodging Court, W-S, NC 27103 336.774.0805 Quality Inn & Suites NBTF Rate: $89, Single/Double 2008 S. Hawthorne Road, W-S, NC 27103 Cut-off date: 7/10/15 336.765.6670 NBTF Rate: $89.00, Single/Double Courtyard Marriott (Hanes Mall Location) Cut-off date: 8/2/15 1600 Westbrook Plaza Dr., W-S, NC 27103 336.760.5777 Residence Inn by Marriott NBTF Rate: $99, King/Double 7835 North Point Blvd., W-S, NC 27106 336.759.0777 Courtyard Winston-Salem (University) NBTF Rate: $129 Studio, $170 Penthouse 3111 University Parkway, W-S, NC 27105 Cut-off date: 7/7/15 800.321.2211; 336.727.1277 NBTF Rate: $99, Single/Double Springhill Suites (Hanes Mall) Cut-off date: 7/13/15 1015 Marriott Crossing Way, W-S, NC 27103 336.765.0190 ext.