Solar Skyspace B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Renewable Portfolio Standards: an Assessment of Regional Supply and Demand Conditions Affecting the Future of Renewable Energy in the West

(This page intentionally left blank) Beyond Renewable Portfolio Standards: An Assessment of Regional Supply and Demand Conditions Affecting the Future of Renewable Energy in the West David J. Hurlbut, Joyce McLaren, and Rachel Gelman National Renewable Energy Laboratory Prepared under Task No. AROE.2000 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report 15013 Denver West Parkway NREL/TP-6A20-57830 Golden, CO 80401 August 2013 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. -

Solar Technical Appendix

STRUCTURAL TECHNICAL APPENDIX 01/15/2015 for Residential Rooftop Solar Installations Structural Technical Appendix for Residential Rooftop Solar Installations (Appendix to California's Solar Permitting Guidebook's Toolkit Structural Document, based on the 2013 California Residential Code and 2013 California Building Code) STRUCTURAL TECHNICAL APPENDIX 01/15/2015 for Residential Rooftop Solar Installations Table of Contents Introduction 4 Overall Intent 4 Criteria for Expedited Permitting are not Limits for other Systems 4 Background/History 4 Purpose of the Structural Technical Appendix 5 Code Basis 5 California Residential Code (CRC) versus California Building Code (CBC) 5 Design Wind Speeds in CRC versus CBC 5 Organization of the Remainder of this Technical Appendix 6 Part 0. Region and Site Checks 8 Assumptions Regarding Snow and Wind Loads 8 Optional Additional Site Checks in Atypical Regions 9 Part 1. Roof Checks 15 Code Compliant Wood-framed Roof 15 1.A. Visual Review 15 Site Auditor Qualifications 15 Digital Photo Documentation 16 1.A.(1). No Reroof Overlays 16 1.A.(2). No Significant Structural Deterioration or Sagging 17 1.B. Roof Structure Data: 18 1.B.+ Optional Additional Rafter Span Check Criteria 18 Choose By Advantage 19 Horizontal Rafter Span Check 20 Prescriptive Rafter Strengthening Strategies 21 Roof Mean Height 22 Part 2. Solar Array Checks 24 2.A. "Flush-Mounted" Rooftop Solar Arrays 24 2.B. Solar Array Self-Weight 24 2.C. Solar Array Covers No More than Half the Total Roof Area 27 2.D. Solar Support Component Manufacturer's Guidelines 27 2.E. Roof Plan of Module and Anchor Layout 27 2.F. -

Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California Quality Careers — Cleaner Lives

Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California Quality Careers — Cleaner Lives DONALD VIAL CENTER ON EMPLOYMENT IN THE GREEN ECONOMY Institute for Research on Labor and Employment University of California, Berkeley November 10, 2014 By Peter Philips, Ph.D. Professor of Economics, University of Utah Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Peter Philips | Donald Vial Center on Employment in the Green Economy | November 2014 1 2 Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California: Quality Careers—Cleaner Lives Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California Quality Careers — Cleaner Lives DONALD VIAL CENTER ON EMPLOYMENT IN THE GREEN ECONOMY Institute for Research on Labor and Employment University of California, Berkeley November 10, 2014 By Peter Philips, Ph.D. Professor of Economics, University of Utah Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Peter Philips | Donald Vial Center on Employment in the Green Economy | November 2014 3 About the Author Peter Philips (B.A. Pomona College, M.A., Ph.D. Stanford University) is a Professor of Economics and former Chair of the Economics Department at the University of Utah. Philips is a leading economic expert on the U.S. construction labor market. He has published widely on the topic and has testified as an expert in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, served as an expert for the U.S. Justice Department in litigation concerning the Davis-Bacon Act (the federal prevailing wage law), and presented testimony to state legislative committees in Ohio, Indiana, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Utah, Kentucky, Connecticut, and California regarding the regulations of construction labor markets. -

Laramie Recreation RFQ Submittal Creative Energies

1 PO Box 1777 Lander, WY 82520 307.332.3410 CEsolar.com [email protected] SUBMITTAL IN RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS Laramie Community Recreation Center / Ice & Events Center 25kW Solar Projects Creative Energies hereby submits the following information as our statement of qualifications to design and install the Laramie Recreation solar projects that have been awarded funding under the Rocky Mountain Power (RMP) Blue Sky Community Projects Funds grant program. Please direct all questions or feedback on this submittal to Eric Concannon at 307-438-0305, by email at [email protected], or by mail to PO Box 1777, Lander, WY 82520. Regards, Eric D. Concannon 2 A. Qualifications and Experience of Key Personnel • Scott Kane Project Role: Contracting Agent Position: Co-Founder, Co-Owner, Business and Human Resource Management, Contracting Agent With Company Since: 2001 Scott is a co-founder and co-owner of Creative Energies and oversees legal and financial matters for the company. Scott was previously certified by the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners (NABCEP) as a Certified PV Installation Professional. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Geology from St. Lawrence University. He was appointed to the Western Governors’ Association’s Clean and Diversified Energy Initiative’s Solar Task Force and is a former board member for the Wyoming Outdoor Council, Wyoming’s oldest conservation non-profit. Scott is a Solar Energy International graduate and frequently makes presentations on renewable energy technology and policy. • Eric Concannon Project Role: Development and Preliminary Design Position: Technical Sales, Lander, WY Office With Company Since: 2012 Certifications: NABCEP Certified PV Technical Sales Professional; LEED AP Building Design + Construction Eric manages all incoming grid-connected solar inquiries for our Lander office, including customer education, pricing, and preliminary design and has developed several successful Blue Sky Grant projects in Wyoming. -

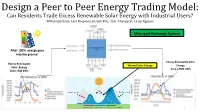

Design P2P Energy Trading

Design a Peer to Peer Energy Trading Model: Can Residents Trade Excess Renewable Solar Energy with Industrial Users? William Jackson, Lara Basyouni, Joseph Kim, Anar Altangerel, Casey Nguyen Microgrid Exchange System After 100%, energy goes into the ground. Excess Renewable Solar Excess Renewable Wasted Solar Energy Energy Solar Energy Area =2503 kWh Area =520 kWh 1 Overview • Context Analysis • Stakeholders • Problem/Need Statement • Confluence Interaction Diagram • Gap Analysis • Concept of Operations • IDEF0 Diagram • Model Simulation • System Requirements • Physical Hierarchy • Model Results • Model Verification Plan • Graphical User Interface • Business Case • System Applications • Conclusion 2 Context Analysis-Cheap Solar • Installed Solar: Price of Solar Energy Trend is projected to drop Opportunity: Lower upfront solar costs goes down to below $50 per mWh in 2024 from $350 per mWh in 2009 . for residential users. Challenge: Technology gap still exists with distribution battery energy storage systems. Those limitations on storage capacity could result in excess solar energy production during peak daytime hours going into the ground. Wasted Solar Energy 1200.00 1000.00 ) 800.00 W n Residential k ( Demand y 600.00 g r e n Residential n “The greatest challenge that solar power faces is energy storage. E 400.00 Solar Generated GMU ENGR Solar arrays can only generate power while the sun is out, so they 200.00 Demand can only be used as a sole source of electricity if they can produce 0.00 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 -

Colorado's Clean Energy Choices

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION What is Clean Energy and Why Is It 1 Good for Colorado GREEN POWER IS CLEAN POWER 4 Wind Power, Solar Power, Hydroelectric Power, Biomass Power, Concentrating Solar Power and Geothermal Energy CLEAN ENERGY AT HOME 14 Climate Responsive and Solar Architecture, Building America: Colorado, Solar Water Heating, and Geothermal Heat Pumps SELF GENERATION FOR FARMERS AND RANCHERS 20 Stand-Alone PV and Small Wind Turbines NEW TRANSPORTATION 24 OPTIONS Clean Cities, Renewable Fuels, and New Cars CHOOSING WISELY 28 Layout and design: Manzanita Graphics, LLC Darin C. Dickson & Barry D. Perow 717 17th Street, Suite 1400 Denver, Colorado 80202 303.292.9298 303.292.9279 www.manzanitagraphics.com WHAT IS CLEAN ENERGY? Take a stroll in Boulder, Renewable energy comes Montrose, Fort Collins, or either directly or indirectly Limon on a typical day and from the sun or from tapping you’ll see and feel two of the heat in the Earth’s core: Colorado’s most powerful ¥ Sunlight, or solar energy, can clean energy resources. The be used directly for heating, sun shines bright in the sky, cooling, and lighting homes and and there is likely to be a other buildings, generating elec- pleasant 15-mph breeze. It’s tricity, and heating hot water. solar energy and wind energy ¥The sun’s heat also causes at your service, part of a broad temperature changes spectrum of clean Gretz, Warren NREL, PIX - 07158 on the Earth’s energy resources surface and in the available to us in air, creating wind Colorado. energy that can Today, 98% of be captured with Colorado’s energy wind turbines. -

Residential Solar Photovoltaics: Comparison of Financing Benefits, Innovations, and Options

Residential Solar Photovoltaics: Comparison of Financing Benefits, Innovations, and Options Bethany Speer NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-51644 October 2012 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Residential Solar Photovoltaics: Comparison of Financing Benefits, Innovations, and Options Bethany Speer Prepared under Task Nos. SM10.2442, SM12.3010 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report 15013 Denver West Parkway NREL/TP-6A20-51644 Golden, Colorado 80401 October 2012 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. -

CSPV Solar Cells and Modules from China

Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Cells and Modules from China Investigation Nos. 701-TA-481 and 731-TA-1190 (Preliminary) Publication 4295 December 2011 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission COMMISSIONERS Deanna Tanner Okun, Chairman Irving A. Williamson, Vice Chairman Charlotte R. Lane Daniel R. Pearson Shara L. Aranoff Dean A. Pinkert Robert B. Koopman Acting Director of Operations Staff assigned Christopher Cassise, Senior Investigator Andrew David, Industry Analyst Nannette Christ, Economist Samantha Warrington, Economist Charles Yost, Accountant Gracemary Roth-Roffy, Attorney Lemuel Shields, Statistician Jim McClure, Supervisory Investigator Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Cells and Modules from China Investigation Nos. 701-TA-481 and 731-TA-1190 (Preliminary) Publication 4295 December 2011 C O N T E N T S Page Determinations.................................................................. 1 Views of the Commission ......................................................... 3 Separate Views of Commission Charlotte R. Lane ...................................... 31 Part I: Introduction ............................................................ I-1 Background .................................................................. I-1 Organization of report......................................................... -

US Solar Industry Year in Review 2009

US Solar Industry Year in Review 2009 Thursday, April 15, 2010 575 7th Street NW Suite 400 Washington DC 20004 | www.seia.org Executive Summary U.S. Cumulative Solar Capacity Growth Despite the Great Recession of 2009, the U.S. solar energy 2,500 25,000 23,835 industry grew— both in new installations and 2,000 20,000 employment. Total U.S. solar electric capacity from 15,870 2,108 photovoltaic (PV) and concentrating solar power (CSP) 1,500 15,000 technologies climbed past 2,000 MW, enough to serve -th MW more than 350,000 homes. Total U.S. solar thermal 1,000 10,000 MW 1 capacity approached 24,000 MWth. Solar industry 494 revenues also surged despite the economy, climbing 500 5,000 36 percent in 2009. - - A doubling in size of the residential PV market and three new CSP plants helped lift the U.S. solar electric market 37 percent in annual installations over 2008 from 351 MW in 2008 to 481 MW in 2009. Solar water heating (SWH) Electricity Capacity (MW) Thermal Capacity (MW-Th) installations managed 10 percent year-over-year growth, while the solar pool heating (SPH) market suffered along Annual U.S. Solar Energy Capacity Growth with the broader construction industry, dropping 10 1,200 1,099 percent. 1,036 1,000 918 894 928 Another sign of continued optimism in solar energy: 865 -th 725 758 742 venture capitalists invested more in solar technologies than 800 542 any other clean technology in 2009. In total, $1.4 billion in 600 481 2 351 venture capital flowed to solar companies in 2009. -

OH One Pager

OHIO The Ohio Conservative Energy Forum (OHCEF) is a conservative clean energy education and advocacy nonprofit. OHCEF is a member of the Conservative Energy Network (CEN), a national coalition of 21 state-based organizations that seek to advance clean energy solutions based on the conservative principles of less government, states' rights, and free markets. Learn more about Ohio's energy mix below and contact us if you have questions or need additional resources. DID YOU KNOW? Ohio is home to over Minster, Ohio is home Nearly 250 Ohio 114,000 clean energy to the first municipal companies are industry jobs. 11.3% solar + storage facility engaged in the clean of these jobs are in the United States. energy supply chain. staffed by Ohio veterans. OH ELECTRIC GENERATION Mix 2000-2018 d e t a r e n e G y g r e n E l a t o T f o % https://www.eia.gov/electricity/state/ *Renewables include: Wind, Solar, Hydro and Biomass **Other includes: Nuclear, Wood, Petroleum, Battery Voters Across the Political Spectrum Support Clean Energy Policies According to a 2019 Statewide Survey Conducted by Public Opinion Strategies 84% 82% 63% of Ohio conservatives of Ohio conservatives of Ohio conservatives want to see at least 25% support allowing utility are more likely to of Ohio’s electricity customers who generate support a politician who come from renewable their own power through supports renewable sources. solar panels to be energy and energy compensated for efficiency. generating more power than they can use. Impact of Wind Energy in OHIO 864 MW #23 ~2,000 Total Installed National Ranking in Wind Jobs Capacity Installed Capacity $1.4B $7M 40% Cumulative Annual State and Cost Decrease Investment Local Tax Payments Over 10 Years https://www.awea.org/resources/fact-sheets/state-facts-sheets IMpact of Solar Power In ohio 264 MW #28 7,282 Total Installed National Ranking in Solar Jobs 3 Capacity1 Installed Capacity2 $702M $17.1M 38% Cumulative Projected Annual Cost Decrease Investment4 Local Tax Revenue5 Over 5 Years 6 1-4, 6. -

Exhibit I Implementing Solar Technologies at Airports

Exhibit I Implementing Solar Technologies at Airports Implementing Solar Technologies at Airports A. Kandt and R. Romero NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Technical Report NREL/TP-7A40-62349 July 2014 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Implementing Solar Technologies at Airports A. Kandt and R. Romero Prepared under Task No. WFG4.1010 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report 15013 Denver West Parkway NREL/TP-7A40-62349 Golden, CO 80401 July 2014 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. -

GREEN AMERICAN GREENAMERICA.ORG in COOPERATION the Big Picture: Green America's Mission Is to Harness Economic Power for a Just and Sustainable Society

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 ISSUE 95 LIVE BETTER. SAVE MORE. INVEST WISELY. GREEN MAKE A DIFFERENCE. AMERICAN INSIDE 4 GMO INSIDE You want to eat organic, buy what you need TARGETS green and Fair Trade, and support renewable CHOBANI energy. But you worry that green can be YOGURT expensive. Is it possible to... REAL GREEN LIVING 6 Go Green FRACKING: THE SITUATION IS GETTING on a Budget? WORSE Page 12 REAL GREEN INVESTING 8 THE FOSSIL-FREE DIVESTMENT MOVEMENT EXPANDS 10 LEAD FOUND IN LIPSTICK SHOWS NEED FOR REFORM DID YOU KNOW? Growing your own salad mix can save you $17.55 for every square foot you plant. Tips for organic 4 ECO ACTIONS on a budget, 10 ACROSS GREEN AMERICA p. 16 23 GREEN BUSINESS NEWS 24 LETTERS & ADVICE Photo by zoryanchik / shutterstock Invest as if our planet depends on it Fossil Fuel Free Balanced Fund You should carefully consider the Funds’ investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses before investing. To obtain a Prospectus that contains this and other information about the Funds, please visit www.greencentury.com, email [email protected], or call 1-800-93-GREEN. Please read the Prospectus carefully before investing. Stocks will fluctuate in response to factors that may affect a single company, industry, sector, or the market as a whole and may perform worse than the market. Bonds are subject to risks including interest rate, credit, and inflation. The Green Century Funds are distributed by UMB Distribution Services, LLC. 3/13 2 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 GREEN AMERICAN GREENAMERICA.ORG IN COOPERATION The Big Picture: Green America's mission is to harness economic power for a just and sustainable society.