20060522-SHAC 7 Memorandum in Opposition to Post-Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

Journal of Animal Law 2005.01.Pdf

VOL. I 2005 JOURNAL OF ANIMAL LAW Michigan State University College of Law J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W VOL. I 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The Gathering Momentum…………………………………………………………………. 1 David Favre ARTICLES & ESSAYS Non-Economic Damages: Where does it get us and how do we get there? ……………….. 7 Sonia Waisman A new movement in tort law seeks to provide money damages to persons losing a companion animal. These non-compensatory damages are highly controversial, and spark a debate as to whether such awards are the best thing for the animals—or for the lawyers. Would a change in the property status of companion animals better solve this important and emotional legal question? Invented Cages: The Plight of Wild Animals in Captivity ………………………………... 23 Anuj Shah & Alyce Miller The rate of private possession of wild animals in the United States has escalated in recent years. Laws at the federal, state, and local levels remain woefully inadequate to the task of addressing the treatment and welfare of the animals themselves and many animals “slip through the cracks,” resulting in abuse, neglect, and often death. This article explores numerous facets of problems inherent in the private possession of exotic animals. The Recent Development of Portugese Law in the Field of Animal Rights ………………. 61 Professor Fernando Arajúo Portugal has had a long and bloody tradition of violence against animals, not the least of which includes Spanish-style bullfighting that has shown itself to be quite resistant to legal, cultural, and social reforms that would respect the right of animals to be free from suffering. -

Joint Civic Committee Endorses Six Candidates for 3 School Board Posts

, •.</.' )'«••. ,,r't » -'% hf-J •I '..• .if •r V II r atxb (^biromcle Second ca»M Postage Paid 15 CENTS Vol. LXXIV. No. 48. 4 Sections, 32 Pages CRANFORD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 14, 1967 CitaiorA, New Jersey 0701* Planning Board Report Salary Hikes of 5-7 Percent Joint Civic Committee Endorses Six Planned for Town Employes Salary increases of 5 to 7 percent for municipal employes, begin- Urges Many Changes ling January 1, are provided in an ordinance approved on. first reading Candidates for 3 School Board Posts >y Township Committee Tuesday night. Public hearing will be De- Six candidates for the Cran- ember 26. brd Board of Education have In Zoning Ordinance Finance Commissioner Wynn Kent estimated the increases, plus ad- been endorsed by the Joint Recommendations for drastic changes in the zoning ordinance as itional personnel including two Me Committee for Encourag- it pertains to the business and industrial zones were contained in a ew policemen, will add about 190,000 to - the township's payroll ing Candidates for the Board lengthy report received Tuesday night by Township Committee from iccount next year. Police Search of Education. Robert Biunno, the Planning Board. The recommendations were referred to the He said the committee had de- eorge Rubine and James Wil- attorney and engineer for review and "hopefully for action early next berated "long and seriously over School After liams, the three members of year," Mayor Edward Gill stated, he magnitude of the increases," the.bodrd completing their the proposed changes. nd had held nieetings with rep- first terms in February, are The mayor commended Howard esentatives of the Patrolmen's Bomb Scare seeking reelection and have been CHS Holiday endorsed. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

Cracking Down on Drugs Emmons Initiates 3-Fold Information Program

Volume 13. Issue 17 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, March 8, 1^89 Along Main Street Cracking Down on Drugs Emmons initiates 3-fold information program In hopes of combating the the state to help fund the fight these kids early because they're helping out with the project." he 3 = small city drug problem. Lowell against drugs." Emmons said. coming in contact with drugs at said. i :r Police Chief Barry Emmons is "As a whole I think the commu- an earlier age."' he adds. By the time the cost for the spearheading a substance abuse nity is aware of the drug problem The drug abuse program will booklets, video, coloring books information program which he and the job that lies ahead of us. then filter in to the middle school and time donated by the police hopes will allow city enforce- Emmons spoke highly of the and high school levels. The high and rescue departments are to- ment officers to come in contact support local businesses have school program will be similar taled. the expense will be YMCA BEGINS YOUTH PCX)L FUND CAMPAIGN with the youth before they are given the substance abuse prog- to the adult awareness program. roughly $10-$ 12,000. approached by drug dealers. ram. "It's our intention to make The cost for the drug awareness, The project has received a The Lowell VMCA has kicked otTils Invest in Youth/Pool Fund The program is a three-fold op- this an on-going program." Em- child watch and crime watch grant from the LOOK Fund and Campaign. -

DISNEY STILLS LIST Last Updated on October 7, 2020 This Is a List of All

DISNEY STILLS LIST Last updated on October 7, 2020 This is a list of all of the extra Disney publicity photos I have available for trade or for sale. They're all Disney originals, not duplicates, and are extra copies of those I have in my own collection. The photos are $3/each unless marked below, plus $7.50 per order for Priority Mail in the United States. Photos marked "Free" are just that - get one free for every photo you buy. I am willing to trade two-for-one for any Disney photos I don't have (which is a lot more than what's on this list!), or for other Disneyana. Please let me know what you have to trade! I have multiple copies of some photos but just one of others, so it's first-come, first-served. If you have any questions or want me to hold photos for you please let me know. $1,000,000 DUCK Cast: Dean Jones (Professor Albert Dooley), Sandy Duncan (Katie Dooley), Joe Flynn (Finley Hooper). 51A-1636 Albert looks at Charley in cage; Hooper looks at both of them 51A-2299 Publicity: Sandy Duncan leaning on Dean Jones, both smiling 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA Cast: Kirk Douglas (Ned Land), James Mason (Captain Nemo), Paul Lukas (Professor Pierre Aronnax), Peter Lorre (Conseil), Robert J. Wilke (First Mate). TWC-39 Divers securing coral cross TWC-136 Divers working with net in underwater plants TWC-158 Divers placing coral cross on the underwater grave TWC-196 Behind-the-scenes: Crew members with underwater signal chart TWC-197 Behind-the-scenes: Crew practicing underwater signals TWC-204 Behind-the-scenes: Crew lowers camera into -

Animal People News

July/August 2008 3/22/13 9:09 PM Page 1 Feds funding egg industry No big effort to defeat California anti- SAN FRANCISCO––U.S. Agricul- veal calves in crates that prevent them from ture Secretary Ed Schaefer personally approved turning around and extending their limbs. giving $3 million collected from egg producers The American Egg Board money Olympic for co-promotions by the American Egg Board would more than double the campaign fund in to the agribusiness campaign against the opposition to Proposition Two, which had California Prevention of Farm Animal Cruelty raised $2.16 million as of August 12, 2008, Act, alleges a lawsuit filed on August 13, 2008 according to the California Secretary of State’s wins for by Californians for Humane Farms. office. Supporters had raised $4.3 million, The California Prevention of Farm $3.5 of it from the Humane Society of the U.S. Animal Cruelty Act, Proposition Two on the and individual HSUS employees. The United 2008 California state ballot, would reduce the Egg Producers Association has predicted that animals stocking density for caged laying hens by 2015, animal use industries will need to spend about and after 2015 would prohibit raising pigs and $50 million to defeat Proposition Two. Californians for Humane Farms is the ––but some umbrella for the Yes on Proposition Two com- mittee, whose major funders are Farm Sanctuary and the Humane Society of the U.S. “As reported in Egg Industry m a g a - quiet gains zine,” explained a Yes on Proposition Two committee media statement describing the law- B E I J I N G ––Political stress over suit, “the American Egg Board ‘unanimously Tibet and controversies arising from the passed a motion at its 2007 fall meeting in aftermath of the May 12, 2008 Sichuan California that $3 million be held in reserve to earthquake appear to have deferred expec- assist the state if necessary in the industry’s tations that China would introduce a Animal Rescue Beijing volunteer. -

Ecoterrorism: Environmental and Animal-Rights Militants in the United States

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY 07 May 2008 UNIVERSAL ADVERSARY DYNAMIC THREAT ASSESSMENT Ecoterrorism: Environmental and Animal-Rights Militants in the United States EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The term ecological terrorists,1 or ecoterrorists, refers to those individuals who independently and/or in concert with others engage in acts of violence and employ tactics commonly associated with terrorism to further their sociopolitical agenda aimed at animal and/or environmental protection. The ecoterrorist movement is a highly decentralized transnational network bound and driven by common ideological constructs that provide philosophical and moral justification for acts of violence against what it perceives to be the destructive encroachment of modern society on the planet’s habitat and its living organisms.2 The ecoterrorist movement represents the fringe element of the broader ecological and animal- rights community that argues that the traditional methods of conserving and preserving the Earth are insufficient, and is willing to use violence as the principal method of the planet’s defense against anyone “guilty” of exploiting and destroying the Earth. (U//FOUO) The overall strength of the movement is impossible to determine given that individuals who take part in ecoterrorist activities generally lack a common profile and exercise a high level of operational security. Nonetheless, ecoterrorists are known to have a global presence and are particularly active in the industrialized West (North America and Western Europe). In the continental United States (CONUS), militant ecological and animal-rights activists are geographically dispersed and operate in both urban and rural settings. The movement has demonstrated a great deal of tactical and strategic sophistication. -

Taking a Bite out of Crime

PROMOTE YOUR BUSINESS HERE! Connect Yes, in this very spot! EVERYDAY Log on Call 310-458-7737 for details Stay local Visit us online at smdp.com FRIDAY, MARCH 13, 2009 Volume 8 Issue 110 Santa Monica Daily Press THOMPSON IS LATEST ADDITION SEE PAGE 14 We have you covered THE ALMOST THERE ISSUE New shelter for families Taking a breaks ground bite out BY MELODY HANATANI Daily Press Staff Writer of crime CULVER CITY The ongoing efforts by Santa Monica city officials to take a regional approach in addressing homelessness took a Violent crime drops giant step forward on Thursday when a locally-based nonprofit broke ground on a 7 percent in Santa new family shelter in a neighboring commu- nity. Monica in 2008 A large crowd of homeless service advo- cates and officials from Los Angeles County BY KEVIN HERRERA and nearby municipalities gathered at the Editor in Chief old Sunbay Motel in Culver City to celebrate the beginning of the roughly five-month- PUBLIC SAFETY FACILITY Violent crimes in long construction of Upward Bound Santa Monica continued to hit historic lows House’s new Family Shelter. in 2008, a trend which SMPD Chief Tim “The opening can’t happen soon enough Jackman credited to increased community for the thousands of families across Los involvement and an intense focus on con- Angeles who are losing their jobs, their necting the homeless population with social homes, their hope,” said David Snow, the service agencies. executive director of Santa Monica-based Part 1 crimes, which include rapes, mur- ders and assaults, were down 7 percent com- SEE HOME PAGE 12 pared to 2007, according to figures released by the SMPD. -

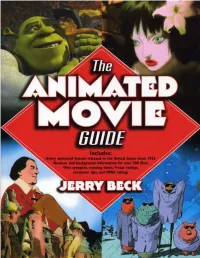

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

UPC Spring 1997 Poultry Press

November 10, 1996 Brandywine Farms Hemet, California by Cherylynn Brown Tbe ostriches were going to the San Diego Airport for transportation to Brussels, Belgium that day. Tbe average value per bird was $875. As we drove down the dirt road we passed a double decker cattle truck packed with ostriches. Tbeir heads extended a couple offeet out of the top ofthe truck. All mouths were open and their eyes looked wild and fearful. ... , Chip has to finish loading the rest of the birds going to the airport, a total of 165 birds. One large trailer is filled with ostriches. I take photos and count 17 birds in the back compartment, about 8 X 12 square feet. Several birds jump into each other and try to run through the wall while crying a high-pitched scream. Handling the Ostriches for Transportation I take pictures of the following scenes: 1) Birds standing with black cloth wrapped around their faces. 2) A person holds a metal hook on an 8 to 10-foot pole while another helps him corner the ostriches. Together they work to put black cloth tubes over the ostriches' heads. Even with the tubes blinding them the birds try to walk or run. 3) One bird has a broken wing. She is being sold for less. 4) As the ostriches are being forced toward the truck, they jump and try to run, swinging the farm workers around. The workers hold onto their tail feathers, ripping them out by the handful. They grab them at the face by the beak. They wrestle the birds into a hold by the neck, then force them to the gate, then into a pathway leading to the truck. -

Crisis Management Guide

Crisis Management Guide 2013 Edition Prepare. Prevent. Protect. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH 8181100 Connecticut Vermont Avenue Avenue NW, NW, Suite Suite 1100 900 Washington, DC 2000520006 Telephone: 202-857-0540, Fax: 202-659-1902 Internet: www.nabr.org E-mail: [email protected] 2 Crisis Management Guide Prepare. Prevent. Protect. TABLE of CONTENTS Introduction Animal Activists Pose a Real Threat to Biomedical Research..........................................................................7 Be Prepared – This Guide is a Roadmap to Readiness......................................................................................9 Seize the Opportunity – Take the Lead Now....................................................................................................10 Assess Section One: Assess..............................................................................................................................................13 Step One: Assemble a Crisis Management Team...........................................................................................13 Step Two: Organize the Team...........................................................................................................................13 Step Three: Mobilize the Team...........................................................................................................................13 Management/Administration.......................................................................................................14 Human Resources................................................................................................................................................14